The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood

(MP3-10,2MB;21'24'')

There were formerly a king and a queen, who were so sorry that they had no children; so sorry that it cannot be expressed. They went to all the waters in the world; vows, pilgrimages, all ways were tried, and all to no purpose.

At last, however, the Queen had a daughter. There was a very fine christening; and the Princess had for her god-mothers all the fairies they could find in the whole kingdom (they found seven), that every one of them might give her a gift, as was the custom of fairies in those days. By this means the Princess had all the perfections imaginable.

After the ceremonies of the christening were over, all the company returned to the King's palace, where was prepared a great feast for the fairies. There was placed before every one of them a magnificent cover with a case of massive gold, wherein were a spoon, knife, and fork, all of pure gold set with diamonds and rubies. But as they were all sitting down at table they saw come into the hall a very old fairy, whom they had not invited, because it was above fifty years since she had been out of a certain tower, and she was believed to be either dead or enchanted.

The King ordered her a cover, but could not furnish her with a case of gold as the others, because they had only seven made for the seven fairies. The old Fairy fancied she was slighted, and muttered some threats between her teeth. One of the young fairies who sat by her overheard how she grumbled; and, judging that she might give the little Princess some unlucky gift, went, as soon as they rose from table, and hid herself behind the hangings, that she might speak last, and repair, as much as she could, the evil which the old Fairy might intend.

In the meanwhile all the fairies began to give their gifts to the Princess. The youngest gave her for gift that she should be the most beautiful person in the world; the next, that she should have the wit of an angel; the third, that she should have a wonderful grace in everything she did; the fourth, that she should dance perfectly well; the fifth, that she should sing like a nightingale; and the sixth, that she should play all kinds of music to the utmost perfection.

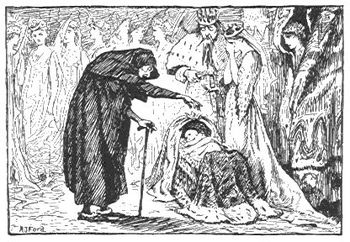

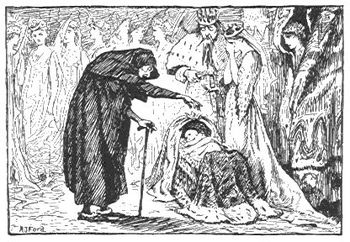

The old Fairy's turn coming next, with a head shaking more with spite than age, she said that the Princess should have her hand pierced with a spindle and die of the wound. This terrible gift made the whole company tremble, and everybody fell a-crying.

At this very instant the young Fairy came out from behind the hangings, and spake these words aloud:

"Assure yourselves, O King and Queen, that your daughter shall not die of this disaster. It is true, I have no power to undo entirely what my elder has done. The Princess shall indeed pierce her hand with a spindle; but, instead of dying, she shall only fall into a profound sleep, which shall last a hundred years, at the expiration of which a king's son shall come and awake her."

The King, to avoid the misfortune foretold by the old Fairy, caused immediately proclamation to be made, whereby everybody was forbidden, on pain of death, to spin with a distaff and spindle, or to have so much as any spindle in their houses. About fifteen or sixteen years after, the King and Queen being gone to one of their houses of pleasure, the young Princess happened one day to divert herself in running up and down the palace; when going up from one apartment to another, she came into a little room on the top of the tower, where a good old woman, alone, was spinning with her spindle. This good woman had never heard of the King's proclamation against spindles.

"What are you doing there, goody?" said the Princess.

"I am spinning, my pretty child," said the old woman, who did not know who she was.

"Ha!" said the Princess, "this is very pretty; how do you do it? Give it to me, that I may see if I can do so."

She had no sooner taken it into her hand than, whether being very hasty at it, somewhat unhandy, or that the decree of the Fairy had so ordained it, it ran into her hand, and she fell down in a swoon.

The good old woman, not knowing very well what to do in this affair, cried out for help. People came in from every quarter in great numbers; they threw water upon the Princess's face, unlaced her, struck her on the palms of her hands, and rubbed her temples with Hungary-water; but nothing would bring her to herself.

And now the King, who came up at the noise, bethought himself of the prediction of the fairies, and, judging very well that this must necessarily come to pass, since the fairies had said it, caused the Princess to be carried into the finest apartment in his palace, and to be laid upon a bed all embroidered with gold and silver.

One would have taken her for a little angel, she was so very beautiful; for her swooning away had not diminished one bit of her complexion; her cheeks were carnation, and her lips were coral; indeed, her eyes were shut, but she was heard to breathe softly, which satisfied those about her that she was not dead. The King commanded that they should not disturb her, but let her sleep quietly till her hour of awaking was come.

The good Fairy who had saved her life by condemning her to sleep a hundred years was in the kingdom of Matakin, twelve thousand leagues off, when this accident befell the Princess; but she was instantly informed of it by a little dwarf, who had boots of seven leagues, that is, boots with which he could tread over seven leagues of ground in one stride. The Fairy came away immediately, and she arrived, about an hour after, in a fiery chariot drawn by dragons.

The King handed her out of the chariot, and she approved everything he had done, but as she had very great foresight, she thought when the Princess should awake she might not know what to do with herself, being all alone in this old palace; and this was what she did: she touched with her wand everything in the palace (except the King and Queen) - governesses, maids of honor, ladies of the bedchamber, gentlemen, officers, stewards, cooks, undercooks, scullions, guards, with their beefeaters, pages, footmen; she likewise touched all the horses which were in the stables, pads as well as others, the great dogs in the outward court and pretty little Mopsey too, the Princess's little spaniel , which lay by her on the bed.

Immediately upon her touching them they all fell asleep, that they might not awake before their mistress and that they might be ready to wait upon her when she wanted them. The very spits at the fire, as full as they could hold of partridges and pheasants, did fall asleep also. All this was done in a moment. Fairies are not long in doing their business.

And now the King and the Queen, having kissed their dear child without waking her, went out of the palace and put forth a proclamation that nobody should dare to come near it.

This, however, was not necessary, for in a quarter of an hour's time there grew up all round about the park such a vast number of trees, great and small, bushes and brambles, twining one within another, that neither man nor beast could pass through; so that nothing could be seen but the very top of the towers of the palace; and that, too, not unless it was a good way off. Nobody doubted but the Fairy gave herein a very extraordinary sample of her art, that the Princess, while she continued sleeping, might have nothing to fear from any curious people.

When a hundred years were gone and passed the son of the King then reigning, and who was of another family from that of the sleeping Princess, being gone a-hunting on that side of the country, asked:

What those towers were which he saw in the middle of a great thick wood?

Everyone answered according as they had heard. Some said:

That it was a ruinous old castle, haunted by spirits.

Others, That all the sorcerers and witches of the country kept there their sabbath or night's meeting.

The common opinion was: That an ogre lived there, and that he carried thither all the little children he could catch, that he might eat them up at his leisure, without anybody being able to follow him, as having himself only the power to pass through the wood.

The Prince was at a stand, not knowing what to believe, when a very good countryman spake to him thus:

"May it please your royal highness, it is now about fifty years since I heard from my father, who heard my grandfather say, that there was then in this castle a princess, the most beautiful was ever seen; that she must sleep there a hundred years, and should be waked by a king's son, for whom she was reserved."

The young Prince was all on fire at these words, believing, without weighing the matter, that he could put an end to this rare adventure; and, pushed on by love and honor, resolved that moment to look into it.

Scarce had he advanced toward the wood when all the great trees, the  bushes, and brambles gave way of themselves to let him pass through; he walked up to the castle which he saw at the end of a large avenue which he went into; and what a little surprised him was that he saw none of his people could follow him, because the trees closed again as soon as he had passed through them. However, he did not cease from continuing his way; a young and amorous prince is always valiant.

He came into a spacious outward court, where everything he saw might have frozen the most fearless person with horror. There reigned all over a most frightful silence; the image of death everywhere showed itself, and there was nothing to be seen but stretched-out bodies of men and animals, all seeming to be dead. He, however, very well knew, by the ruby faces and pimpled noses of the beefeaters, that they were only asleep; and their goblets, wherein still remained some drops of wine, showed plainly that they fell asleep in their cups.

bushes, and brambles gave way of themselves to let him pass through; he walked up to the castle which he saw at the end of a large avenue which he went into; and what a little surprised him was that he saw none of his people could follow him, because the trees closed again as soon as he had passed through them. However, he did not cease from continuing his way; a young and amorous prince is always valiant.

He came into a spacious outward court, where everything he saw might have frozen the most fearless person with horror. There reigned all over a most frightful silence; the image of death everywhere showed itself, and there was nothing to be seen but stretched-out bodies of men and animals, all seeming to be dead. He, however, very well knew, by the ruby faces and pimpled noses of the beefeaters, that they were only asleep; and their goblets, wherein still remained some drops of wine, showed plainly that they fell asleep in their cups.

He then crossed a court paved with marble, went up the stairs and came into the guard chamber, where guards were standing in their ranks, with their muskets upon their shoulders, and snoring as loud as they could. After that he went through several rooms full of gentlemen and ladies, all asleep, some standing, others sitting. At last he came into a chamber all gilded with gold, where he saw upon a bed, the curtains of which were all open, the finest sight was ever beheld - a princess, who appeared to be about fifteen or sixteen years of age, and whose bright and, in a manner, resplendent beauty, had somewhat in it divine. He approached with trembling and admiration, and fell down before her upon his knees.

And now, as the enchantment was at an end, the Princess awaked, and looking on him with eyes more tender than the first view might seem to admit of:

"Is it you, my Prince?" said she to him. "You have waited a long while."

The Prince, charmed with these words, and much more with the manner in which they were spoken, knew not how to show his joy and gratitude; he assured her that he loved her better than he did himself; their discourse was not well connected, they did weep more than talk - little eloquence, a great deal of love. He was more at a loss than she, and we need not wonder at it; she had time to think on what to say to him; for it is very probable (though history mentions nothing of it) that the good Fairy, during so long a sleep, had given her very agreeable dreams. In short, they talked four hours together, and yet they said not half what they had to say.

In the meanwhile all the palace awaked; everyone thought upon their particular business, and as all of them were not in love they were ready to die for hunger. The chief lady of honor, being as sharp set as other folks, grew very impatient, and told the Princess aloud that supper was served up. The Prince helped the Princess to rise; she was entirely dressed, and very magnificently, but his royal highness took care not to tell her that she was dressed like his great-grandmother, and had a point band peeping over a high collar; she looked not a bit less charming and beautiful for all that.

They went into the great hall of looking-glasses, where they supped, and were served by the Princess's officers, the violins and hautboys played old tunes, but very excellent, though it was now above a hundred years since they had played; and after supper, without losing any time, the lord almoner married them in the chapel of the castle, and the chief lady of honor drew the curtains. They had but very little sleep - the Princess had no occasion; and the Prince left her next morning to return to the city, where his father must needs have been in pain for him. The Prince told him:

That he lost his way in the forest as he was hunting, and that he had lain in the cottage of a charcoal-burner, who gave him cheese and brown bread.

The King, his father, who was a good man, believed him; but his mother could not be persuaded it was true; and seeing that he went almost every day a-hunting, and that he always had some excuse ready for so doing, though he had lain out three or four nights together, she began to suspect that he was married, for he lived with the Princess above two whole years, and had by her two children, the eldest of which, who was a daughter, was named Morning, and the youngest, who was a son, they called Day, because he was a great deal handsomer and more beautiful than his sister.

The Queen spoke several times to her son, to inform herself after what manner he did pass his time, and that in this he ought in duty to satisfy her. But he never dared to trust her with his secret; he feared her, though he loved her, for she was of the race of the Ogres, and the King would never have married her had it not been for her vast riches; it was even whispered about the Court that she had Ogreish inclinations, and that, whenever she saw little children passing by, she had all the difficulty in the world to avoid falling upon them. And so the Prince would never tell her one word.

But when the King was dead, which happened about two years afterward, and he saw himself lord and master, he openly declared his marriage; and he went in great ceremony to conduct his Queen to the palace. They made a magnificent entry into the capital city, she riding between her two children.

Soon after the King went to make war with the Emperor Contalabutte, his neighbor. He left the government of the kingdom to the Queen his mother, and earnestly recommended to her care his wife and children. He was obliged to continue his expedition all the summer, and as soon as he departed the Queen-mother sent her daughter-in-law to a country house among the woods, that she might with the more ease gratify her horrible longing.

Some few days afterward she went thither herself, and said to her clerk of the kitchen:

"I have a mind to eat little Morning for my dinner to-morrow."

"Ah! madam," cried the clerk of the kitchen.

"I will have it so," replied the Queen (and this she spoke in the tone of an Ogress who had a strong desire to eat fresh meat), "and will eat her with a sauce Robert ."

The poor man, knowing very well that he must not play tricks with Ogresses, took his great knife and went up into little Morning's chamber. She was then four years old, and came up to him jumping and laughing, to take him about the neck, and ask him for some sugar-candy. Upon which he began to weep, the great knife fell out of his hand, and he went into the back yard, and killed a little lamb, and dressed it with such good sauce that his mistress assured him that she had never eaten anything so good in her life. He had at the same time taken up little Morning, and carried her to his wife, to conceal her in the lodging he had at the bottom of the courtyard.

About eight days afterward the wicked Queen said to the clerk of the kitchen, "I will sup on little Day."

He answered not a word, being resolved to cheat her as he had done before. He went to find out little Day, and saw him with a little foil in his hand, with which he was fencing with a great monkey, the child being then only three years of age. He took him up in his arms and carried him to his wife, that she might conceal him in her chamber along with his sister, and in the room of little Day cooked up a young kid, very tender, which the Ogress found to be wonderfully good.

This was hitherto all mighty well; but one evening this wicked Queen said to her clerk of the kitchen:

"I will eat the Queen with the same sauce I had with her children."

It was now that the poor clerk of the kitchen despaired of being able to deceive her. The young Queen was turned of twenty, not reckoning the hundred years she had been asleep; and how to find in the yard a beast so firm was what puzzled him. He took then a resolution, that he might save his own life, to cut the Queen's throat; and going up into her chamber, with intent to do it at once, he put himself into as great fury as he could possibly, and came into the young Queen's room with his dagger in his hand. He would not, however, surprise her, but told her, with a great deal of respect, the orders he had received from the Queen-mother.

"Do it; do it" (said she, stretching out her neck). "Execute your orders, and then I shall go and see my children, my poor children, whom I so much and so tenderly loved."

For she thought them dead ever since they had been taken away without her knowledge.

"No, no, madam" (cried the poor clerk of the kitchen, all in tears); "you shall not die, and yet you shall see your children again; but then you must go home with me to my lodgings, where I have concealed them, and I shall deceive the Queen once more, by giving her in your stead a young hind."

Upon this he forthwith conducted her to his chamber, where, leaving her to embrace her children, and cry along with them, he went and dressed a young hind, which the Queen had for her supper, and devoured it with the same appetite as if it had been the young Queen. Exceedingly was she delighted with her cruelty, and she had invented a story to tell the King, at his return, how the mad wolves had eaten up the Queen his wife and her two children.

One evening, as she was, according to her custom, rambling round about the courts and yards of the palace to see if she could smell any fresh meat, she heard, in a ground room, little Day crying, for his mamma was going to whip him, because he had been naughty; and she heard, at the same time, little Morning begging pardon for her brother.

The Ogress presently knew the voice of the Queen and her children, and being quite mad that she had been thus deceived, she commanded next morning, by break of day (with a most horrible voice, which made everybody tremble), that they should bring into the middle of the great court a large tub, which she caused to be filled with toads, vipers, snakes, and all sorts of serpents, in order to have thrown into it the Queen and her children, the clerk of the kitchen, his wife and maid; all whom she had given orders should be brought thither with their hands tied behind them.

They were brought out accordingly, and the executioners were just going to throw them into the tub, when the King (who was not so soon expected) entered the court on horseback (for he came post) and asked, with the utmost astonishment, what was the meaning of that horrible spectacle.

No one dared to tell him, when the Ogress, all enraged to see what had happened, threw herself head foremost into the tub, and was instantly devoured by the ugly creatures she had ordered to be thrown into it for others. The King could not but be very sorry, for she was his mother; but he soon comforted himself with his beautiful wife and his pretty children.

La bella addormentata nel bosco

C’erano una volta un re e una regina che si dispiacevano molto di non aver avuto bambini; non si può dire quanto fossero dispiaciuti. Le avevano provate tutte; voti, pellegrinaggi, era stata tentata ogni via, e tutto invano.

Alla fine, comunque, la Regina ebbe una figlia. Si tenne un bellissimo battesimo; la principessa ebbe come madrine tutte le fate che riuscirono a trovare nell’intero regno (ne trovarono sette), ciascuna delle quali le avrebbe fatto un dono, come usano le fate in simili circostanze. Da ciò si capisce che la Principessa ebbe tutte le doti immaginabili.

Dopo che la cerimonia di battesimo fu terminata, tutta la compagnia tornò al palazzo del Re, in cui era stata preparata una grande festa per le fate. Davanti a ognuna di loro era stato posto un magnifico velo con una custodia d’oro massiccio nella quale c’erano un cucchiaio, un coltello e una forchetta, tutti d’oro puro tempestati di diamanti e di rubini. Si erano appena seduti tutti a tavola che videro entrare nella sala una vecchissima fata, che non era stata invitata perché erano più di cinquant’anni che non usciva da una determinata torre, e si credeva che fosse morta o stregata.

Il Re ordinò per lei un velo, ma non avrebbe potuto offrirle la custodia d’oro come alle altre, perché ne aveva fatte fare solo sette per le sette fate. La vecchia Fata ritenne di aver subito un affronto, e mormorò alcune minacce tra i denti. Una delle fate più giovani che sedeva vicino a lei, per caso udì ciò che aveva borbottato; e, ritenendo che avrebbe potuto offrire alla principessina un dono infausto, il più presto possibile si alzò da tavola e si nascose dietro le tende, da dove avrebbe potuto parlare per ultima e riparare, per quanto poteva, il male che la vecchia Fata si sarebbe ripromessa.

Nel frattempo tutte le fate cominciarono a offrire i loro doni alla Principessa. La più giovane le offrì come dono che sarebbe stata la persona più bella al mondo; la successiva che avrebbe avuto l’intelligenza di un angelo; la terza che avrebbe fatto ogni cosa con indicibile grazia; la quarta che avrebbe danzato benissimo; la quinta che avrebbe cantato come un usignolo; e la sesta che avrebbe suonato alla perfezione ogni genere di musica.

Fu il turno della vecchia Fata di avvicinarsi, con la testa più tremolante che per l’età, e disse che la principessa si sarebbe punta una mano con un fuso e sarebbe morta per la ferita. Questo terribile dono gettò nello sconforto tutta la compagnia e ciascuno cominciò a piangere.

A quel punto la giovane fata venne fuori da dietro le tende e disse a voce alta queste parole:

”Vi assicuro, o Re e Regina, che vostra figlia non morirà di tale sventura. È vero, non ho il potere di annullare completamente ciò che un mio superiore ha fatto. La Principessa si pungerà davvero con un fuso; ma, invece di morire, cadrà in un sonno profondo che durerò cento anni, al termine dei quali verrà un figlio di re e la sveglierà.”

Il re, per scongiurare la sfortuna predetta dalla vecchia fata, fece immediatamente un proclama nel quale fosse proibito a tutti, pena la morte, di filare con rocca e fuso, o di tenere in casa qualcosa di simile a un fuso. Circa quindici o sedici anni dopo, il Re e la regina si erano recati in una delle loro dimore di villeggiatura, accadde che la giovane Principessa, per divertirsi, un giorno si mise a percorre in su e in giù il palazzo; andando da un stanza all’altra, arrivò in una cameretta in cima alla torre, in cui una vecchia, sola, stava filando con il fuso. La brava donna non aveva sentito il proclama del Re contro i fusi.

”Che cosa state facendo, dolcezza?” disse la Principessa. “Sto filando, mia graziosa bambina,” disse la vecchia, che non sapeva chi lei fosse.

La Principessa disse: ”Ah! È davvero piacevole; come fai? Dammelo, così che possa vedere se posso farlo.”

L’aveva appena preso in mano, sia che l’avesse fatto troppo frettolosamente piuttosto che fosse stata maldestra, oppure che il pronostico della fata si dovesse avverare, le si conficcò nella mano e lei cadde svenuta.

La buona vecchia, non sapendo bene che fare in quella situazione, gridò per chiedere aiuto. Da ogni dove accorse gente in quantità; gettarono acqua sul viso della principessa, le slacciarono il vestito, batterono le palme delle sue mani, le strofinarono le tempie con acqua d’Ungheria , ma nulla le fece riprendere i sensi.

E intanto il re, che era accorso al rumore, si rammentò della predizione delle fate e, ritenendo che si darebbe dovuta necessariamente avverare, come le fate avevano detto, ordinò che la Principessa fosse portata nella stanza più bella del palazzo e adagiata su un letto tutto ricamato d’oro e d’argento.

La si sarebbe potuta scambiare per un angioletto, tanto era bella; perché la perdita dei sensi non aveva intaccato nemmeno un po’ il suo colorito; le guance erano rosa, e le labbra corallo; in effetti gli occhi erano chiusi, ma la si sentiva respirare dolcemente, il che rassicurava tutti che non fosse morta. Il re comandò che non la disturbassero, ma la lasciassero dormire tranquilla finché fosse giunta l’ora del suo risveglio.

La buona Fata, che le aveva salvato la vita disponendo che dormisse cento anni, si trovava nel regno di Matakin, a dodici mila leghe di distanza, quando alla Principessa accadde l’incidente; tuttavia ne fu istantaneamente informata da un piccolo gnomo, che calzava gli stivali delle sette leghe e con i quali poteva percorrere oltre sette leghe di strada ad ogni passo. La fata venne via immediatamente e arrivò, poco dopo un’ora, in un cocchio di fuoco trainato da draghi.

Il Re l’aiutò a scendere dal cocchio e lei approvò tutto ciò che era stato fatto; ma siccome era assai prudente, pensò che quando la principessa si fosse svegliata, non avrebbe trovato nessuno accanto a lei, trovandosi sola in tutto il palazzo; ed ecco che cosa fece: con la bacchetta toccò toccò ogni cosa nel palazzo (eccetto il Re e la Regina) – governanti, damigelle d’onore, dame di camera, gentiluomini, ufficiali, maggiordomi, cuochi, aiutanti cuochi, sguatteri, guardie, con il loro corpo di guardia, paggi, valletti; allo stesso modo toccò tutti i cavalli nelle stalle, sellati e non, i grossi cani nel cortile e anche il piccolo grazioso Mopsey, il piccolo spaniel della principessa, che giaceva sul letto accanto a lei.

Immediatamente al suo tocco tutti caddero addormentati, non si sarebbero svegliati prima della loro padroncina e sarebbero stati pronti quando lei li avesse cercati. Persino gli stessi spiedi sul fuoco, carichi com’erano di pernici e di fagiani, caddero addormentati. Accadde tutto in un momento. Le fate non si dilungano molto nelle loro azioni.

A quel punto il Re e la regina, dopo aver baciato la loro amata figlia senza che si svegliasse, uscirono dal palazzo e emanarono un editto affinché nessuno osasse avvicinarsi.

Per quanto non fosse necessario, perché in un quarto d’ora crebbero tutt’intorno al parco un gran numero di alberi, grandi e piccoli, cespugli e rovi, intrecciati gli uni con gli altri, tanto che nessun uomo o animale sarebbe potuto passarci attraverso; così che non si sarebbe potuto vedere niente neppure dalle torri più alte del palazzo; e che, inoltre, nondimeno avrebbe tenuto a distanza. Nessuno può dubitare che la Fata avesse dato qui un efficace prova delle sue arti, e che la principessa, mentre continuava a dormire, non avrebbe avuto nulla da temere dalla gente curiosa.

Quando fu trascorso un secolo e passò il figlio del Re che stava regnando, e che era un’altra famiglia rispetto a quella della Principessa addormentata, andando a caccia in quella parte del regno, chiese:

Che cosa fossero quelle torri che vedeva nel mezzo di una grande e fitta foresta?

Ognuno rispose secondo ciò che aveva sentito. Alcuni dissero:

Era un vecchio castello in rovina, infestato dagli spiriti.

Altri, che tutte le maghe e le streghe del regno tenessero lì il loro sabba o gli incontri notturni.

L’opinione diffusa era: ci vive un orco e porta laggiù tutti i bambini che riesce a catturare, e che vorrebbe mangiare a proprio comodo, senza che nessuno sia in grado di seguirlo, in quanto solo lui ha il potere di passare attraverso la foresta.

Il Principe rimase fermo, non sapendo a che cosa credere, quando un bravo campagnolo gli disse così:

”Piacendo a vostra altezza reale, sono circa cinquant’anni ora che ho udito da mio padre, il quale lo sentì dire da mio nonno, che in quel castello c’era una principessa, la più bella mai vista; che deve dormire cento anni e che sarà svegliata da un figlio di re, al quale lei è destinata.”

A queste parole il giovane principe s’infiammò, credendo, senza dar troppo peso alla faccenda, che avrebbe potuto segnare la fine di questa insolita avventura; e, combattuto tra onore e amore, decise in quell’istante di guardare dentro.

Stava avanzando a fatica verso la foresta quando tutti i grandi  alberi, i cespugli e i rovi si fecwero da parte per lasciarlo attraversare; andò verso il castello che vide alla fine di un lungo viale sul quale s’incamminò; e fu un po’ sorpreso quando vide che nessuno dei suoi lo seguiva, perché gli alberi si richiudevano appena lui era passato attraverso. In ogni modo, non smise di proseguire il cammino; un giovane principe innamorato è sempre coraggioso. Giunse in uno spazioso cortile esterno, dove tutto ciò che vide avrebbe raggelato di terrore la persona più coraggiosa. Ovunque regnava il silenzio più spaventoso; l’immagine della morte si manifestava dappertutto, e non si vedevano niente altro che corpi distesi di uomini e animali, che sembravano come morti. Tuttavia capì bene dalle carnagioni rosee e dai nasi foruncolosi delle guardie che erano solo addormentati; e i loro calici, nei quali erano rimaste alcune gocce di vino, mostravano chiaramente come fossero caduti addormentati sulle coppe.

alberi, i cespugli e i rovi si fecwero da parte per lasciarlo attraversare; andò verso il castello che vide alla fine di un lungo viale sul quale s’incamminò; e fu un po’ sorpreso quando vide che nessuno dei suoi lo seguiva, perché gli alberi si richiudevano appena lui era passato attraverso. In ogni modo, non smise di proseguire il cammino; un giovane principe innamorato è sempre coraggioso. Giunse in uno spazioso cortile esterno, dove tutto ciò che vide avrebbe raggelato di terrore la persona più coraggiosa. Ovunque regnava il silenzio più spaventoso; l’immagine della morte si manifestava dappertutto, e non si vedevano niente altro che corpi distesi di uomini e animali, che sembravano come morti. Tuttavia capì bene dalle carnagioni rosee e dai nasi foruncolosi delle guardie che erano solo addormentati; e i loro calici, nei quali erano rimaste alcune gocce di vino, mostravano chiaramente come fossero caduti addormentati sulle coppe.

Allora attraversò un cortile pavimentato di marmo, salì le scale e entrò nella stanza di guardia, in cui le guardie stavano in fila, con i moschetti sulle spalle, russando il più sonoramente possibile. Poi passò attraverso varie stanze piene di cavalieri e di dame, tutti addormentati, alcuni in piedi, altri seduti. Infine arrivò in una camera tutta dorata, in cui vide vicino su un letto, le cui cortine erano tutte aperte, lo spettacolo più bello che avesse mai scorto – una principessa, che sembrava avere quindici o sedici anni, risplendente di una bellezza radiosa che aveva qualcosa di divino. Si avvicinò con un fremito e con ammirazione, e cadde in ginocchio davanti a lei.

E così, siccome l’incantesimo era spezzato, la principessa si svegliò e lo guardò con il più tenero sguardo che il primo incontro avrebbe potuto consentire:

”Siete voi, mio principe?” gli disse. “Dovete aver atteso davvero a lungo.”

Il Principe, affascinato da quelle parole, e ancor di più da modo in cui erano state pronunciate, non sapeva come dimostrare la gioia e la gratitudine; le assicurò che l’avrebbe amata più di se stesso; il loro discorso non era molto coerente, piansero più che parlare – poca eloquenza, moltissimo amore. Era tanto perplesso quanto lei, e non dobbiamo meravigliarcene; lei aveva avuto tempo per pensare a che cosa dirgli; perché è molto probabile (benché la storia non ne faccia menzione) che la buona fata, in un sonno così lungo, le abbia inviato sogni assai piacevoli. Per farla breve, parlarono per quattro ore e non si dissero neppure la metà di ciò che volevano dirsi.

Nel frattempo si svegliò tutto il palazzo; ognuno torno alla propria occupazione e siccome nessuno di loro era innamorato, si sentivano morire di fame. La prima dama d’onore, ansiosa come gli altri cortigiani, si alzo impaziente e disse a voce alta alla Principessa che la cena era servita. Il Principe aiutò la Principessa ad alzarsi; era completamente abbigliata, e in modo magnifico, ma sua altezza reale si guardò bene dal dirle che era vestita come la sua bisnonna, e aveva un nastro rigido che faceva capolino dall’alto colletto, ma non appariva meno affascinante e bella per questo.

Andarono in una grande sala degli specchi, dove cenarono, e furono serviti dagli attendenti della principessa, i violini e gli oboi suonarono melodie vecchie, ma davvero eccellenti, benché fosse un centinaio d’anni che avevano suonato; e dopocena, senza perdere tempo, il lord elemosiniere li unì in matrimonio nella cappella del castello, e la prima dama d’onore tirò le cortine. Dormirono assai poco – la Principessa non ne aveva necessità; il principe la lasciò la mattina seguente per tornare in città, dove suo padre doveva essere in pena per lui. Il Principe gli disse:

Che si era smarrito nella foresta in cui stava cacciando e che aveva trovato ricovero nella casetta di un carbonaio, che gli aveva offerto formaggio e pane scuro.

Il Re, suo padre, che era un buon uomo, gli credette; ma sua madre non era convinta che fosse la verità; e vedendo che andava a caccia ogni giorno, e che aveva sempre qualche scusa pronta per farlo, ma essendo stato fuori tre o quattro notti insieme, lei cominciò a sospettare che si fosse sposato, dal momento che visse con la principessa più di due interi anni ed ebbe da lei due bambini, il maggiore dei quali, che era una figlia, fu chiamato Mattina, e il più piccolo, che era un figlio, Giorno, perché era di gran lunga più affascinante e bello della sorella.

La Regina parlò varie volte con il figlio, per scoprire in che modo passasse il tempo, e che riguardo a ciò aveva il dovere di accontentarla. Ma lui non osò mai confidarle il proprio segreto; la temeva, benché l’amasse, perché apparteneva alla razza degli Orchi, e il Re non l’avrebbe mai sposata se non fosse stato per le sue enormi ricchezze; si era sempre mormorato a corte che avesse le tendenze degli Orchi, e che, ogni volta in cui vedeva passare un bambino, aveva grandissima difficoltà a trattenersi dal gettarsi su di lui. Ecco perché il Principe non le avrebbe mai detto una sola parola.

Ma quando il Re fu morto, il che accadde circa due anni dopo, e si ritrovò signore e padrone, annunciò pubblicamente il proprio matrimonio; e con una gran cerimonia condusse a palazzo la sua Regina. Fecero un magnifico ingresso nella capitale, e lei cavalcava tra i suoi due bambini.

Poco dopo il re mosse guerra all’Imperatore Contalabutte, suo vicino. Lasciò il governo del regno alla regina sua madre e le raccomandò caldamente di aver cura di sua moglie e dei bambini. Era costretto a protrarre la spedizione per tutta l’estate e appena se ne fu andato, la Regina madre mandò la nuora in una villa di campagna tra i boschi, per poter soddisfare con la maggior facilità possibile il proprio orribile desiderio.

Alcuni giorni dopo andò lei stessa laggiù e disse all’addetto della cucina:

”Domani ho intenzione di mangiare la piccola Mattina per pranzo.”

”Ah! Mia signora!” gridò l’addetto della cucina.

”Farò così,” replicò la Regina (e disse ciò con il tono di un’Orchessa che abbia grandissimo desiderio di mangiare carne fresca), e la mangerò con la salsa Robert.”

Il poveruomo, sapendo bene di non poter giocare un tiro mancino all’Orchessa, prese il coltello e andò nella camera della piccola Mattina. A quel tempo aveva quattro anni e andò verso di lui saltando e ridendo, per gettarglisi al collo e chiedergli un po’ di caramelle di zucchero. A quel punto egli cominciò a piangere, il grosso coltello gli cadde di mano e andò nel cortile posteriore, dove uccise un agnello e lo condì con una salsa così buona che la sua padrona gli assicurò di non aver mai mangiato nulla di tanto buono in vita propria. Nello stesso tempo prese la piccola mattina e la portò da sua moglie, per nasconderla nell’alloggio che aveva in fondo al cortile.

Circa otto giorni dopo la perfida Regina disse all’addetto della cucina: “A cena mangerò il piccolo Giorno.”

Lui non rispose una parola, risoluto ad ingannarla come aveva fatto la volta precedente. Andò a prendere il piccolo Giorno e lo vide con un piccolo fioretto in mano, con il quale stava tirando di scherma con una grossa scimmia, un bimbo che aveva solo tre anni. Lo prese tra le braccia e lo portò da sua moglie, che lo avrebbe nascosto nella propria camera da letto insieme con la sorella, e al posto del piccolo Giorno cucinò un ragazzino, assai tenero, che l’Orchessa trovò meravigliosamente buono.

Fino a quel momento era andato tutto bene; ma una sera la perfida Regina disse all’addetto della cucina:

”Mangerò la Regina con la medesima salsa dei suoi bambini.”

A questo punto il povero addetto alla cucina perse la speranza di riuscire a ingannarla. La giovane Regina andava per i vent’anni, senza contare i cento in cui aveva dormito; e come trovare in cortile un animale così sodo era ciò che lo rendeva perplesso. Allora prese la decisione, che avrebbe potuto salvargli la vita, di tagliare la gola della Regina; ed entrando nella sua camera da letto, con l’intenzione di farlo, cercò di infuriarsi il più possibile e andò nella stanza della giovane Regina con il pugnale in mano. Tuttavia non voleva coglierla di sorpresa e le rivelò, con grande riguardo, gli ordini che aveva ricevuto dalla Regina madre.

”Fallo, fallo.” (disse lei, offrendogli la gola). “Esegui i suoi ordini e così io me andrò e vedrò i miei bambini, i miei poveri bambini, che ho amato tanto e così teneramente.”

Infatti lei credeva che fossero morti sin da quando li avevano portati via a sua insaputa.

”No, no, mia signora;” (gridò in lacrime il povero addetto alla cucina) “Non morirete e rivedrete e vostri bambini; ma dovete venire a casa con me nelle mie stanze, dove li ho nascosti, e io ingannerò la regina ancora una volta, dandole una giovane cerva in vostra vece .”

Dopo che l’ebbe condotta subito nella propria camera da letto, dove la lasciò ad abbracciare i suoi bambini e a piangere con loro, andò e condì una giovane cerva, che la Regina mangiò a cena, e la divorò con il medesimo appetito come fosse stata la giovane Regina. Fu estremamente contenta della propria crudeltà e inventò una storia da raccontare al Re al suo ritorno, di come i lupi furiosi avessero sbranato la Regina sua moglie e i suoi due bambini.

Una sera, mentre come il solito vagava per le corti e i cortili del palazzo per fiutare carne fresca, sentì piangere il piccolo Giorno in una stanza al pianoterra, perché la sua mamma lo stava fustigando poiché era stato capriccioso, e udì, nel medesimo tempo, Mattina implorare perdono per il fratello.

L’Orchessa ben presto riconobbe la voce della regina e dei suoi bambini, e quasi folle per essere stata così raggirata, ordinò che il mattino seguente, alle prime luci del giorno (con voce così orribile che fece tremare tutti), fosse portata in mezzo al cortile una grande tinozza, che fece riempire di rospi, vipere, serpi e ogni sorta di serpenti, affinché vi fossero gettati la regina e i suoi bambini, l’addetto alla cucina, sua moglie e la domestica; tutti loro aveva dato ordini che fossero gettati là con le mani legate dietro.

Furono quindi condotti e i carnefici stavano per gettarli nella tinozza quando il Re (che non era certo atteso così presto) entrò a cavallo nel cortile e chiese, con estremo stupore, che cosa significasse quell’orribile spettacolo.

Nessuno osò rispondergli, quando l’Orchessa, furibonda nel vedere ciò che era accaduto, sporse la testa nella tinozza e fu subito divorata dalle disgustose creature che aveva ordinato vi fossero gettate per gli altri. Il Re suo malgrado ne fu dispiaciuto, perché era sua madre, ma subito si consolò con la sua meravigliosa moglie e i suoi graziosi bambini.

Lang non riporta l'origine di questa fiaba, che appartiene alla tradizione europea. La versione a noi più nota è quella di Charles Perrault (NdT)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)