The Water-Lily. The Golden Spinners

(MP3-15'29'')

Once upon a time, in a large forest, there lived an old woman and three maidens. They were all three beautiful, but the youngest was the fairest. Their hut was quite hidden by trees, and none saw their beauty but the sun by day, and the moon by night, and the eyes of the stars. The old woman kept the girls hard at work, from morning till night, spinning gold flax into yarn, and when one distaff was empty another was given them, so they had no rest. The thread had to be fine and even, and when done was locked up in a secret chamber by the old woman, who twice or thrice every summer went a journey. Before she went she gave out work for each day of her absence, and always returned in the night, so that the girls never saw what she brought back with her, neither would she tell them whence the gold flax came, nor what it was to be used for.

Now, when the time came round for the old woman to set out on one of these journeys, she gave each maiden work for six days, with the usual warning: "Children, don't let your eyes wander, and on no account speak to a man, for, if you do, your thread will lose its brightness, and misfortunes of all kinds will follow." They laughed at this oft-repeated caution, saying to each other: "How can our gold thread lose its brightness, and have we any chance of speaking to a man?"

On the third day after the old woman's departure a young prince, hunting in the forest, got separated from his companions, and completely lost. Weary of seeking his way, he flung himself down under a tree, leaving his horse to browse at will, and fell asleep.

The sun had set when he awoke and began once more to try and find his way out of the forest. At last he perceived a narrow foot-path, which he eagerly followed and found that it led him to a small hut. The maidens, who were sitting at the door of their hut for coolness, saw him approaching, and the two elder were much alarmed, for they remembered the old woman's warning; but the youngest said: "Never before have I seen anyone like him; let me have one look." They entreated her to come in, but, seeing that she would not, left her, and the Prince, coming up, courteously greeted the maiden, and told her he had lost his way in the forest and was both hungry and weary.

She set food before him, and was so delighted with his conversation that she forgot the old woman's caution, and lingered for hours. In the meantime the Prince's companions sought him far and wide, but to no purpose, so they sent two messengers to tell the sad news to the King, who immediately ordered a regiment of cavalry and one of infantry to go and look for him.

After three days' search, they found the hut. The Prince was still sitting by the door and had been so happy in the maiden's company that the time had seemed like a single hour. Before leaving he promised to return and fetch her to his father's court, where he would make her his bride. When he had gone, she sat down to her wheel to make up for lost time, but was dismayed to find that her thread had lost all its brightness. Her heart beat fast and she wept bitterly, for she remembered the old woman's warning and knew not what misfortune might now befall her.

The old woman returned in the night and knew by the tarnished thread what had happened in her absence. She was furiously angry and told the maiden that she had brought down misery both on herself and on the Prince. The maiden could not rest for thinking of this. At last she could bear it no longer, and resolved to seek help from the Prince.

As a child she had learned to understand the speech of birds, and this was now of great use to her, for, seeing a raven pluming itself on a pine bough, she cried softly to it: "Dear bird, cleverest of all birds, as well as swiftest on wing, wilt thou help me?" "How can I help thee?" asked the raven. She answered: "Fly away, until thou comest to a splendid town, where stands a king's palace; seek out the king's son and tell him that a great misfortune has befallen me." Then she told the raven how her thread had lost its brightness, how terribly angry the old woman was, and how she feared some great disaster. The raven promised faithfully to do her bidding, and, spreading its wings, flew away. The maiden now went home and worked hard all day at winding up the yarn her elder sisters had spun, for the old woman would let her spin no longer. Toward evening she heard the raven's "craa, craa," from the pine tree and eagerly hastened thither to hear the answer.

By great good fortune the raven had found a wind wizard's son in the palace garden, who understood the speech of birds, and to him he had entrusted the message. When the Prince heard it, he was very sorrowful, and took counsel with his friends how to free the maiden. Then he said to the wind wizard's son: "Beg the raven to fly quickly back to the maiden and tell her to be ready on the ninth night, for then will I come and fetch her away." The wind wizard's son did this, and the raven flew so swiftly that it reached the hut that same evening. The maiden thanked the bird heartily and went home, telling no one what she had heard.

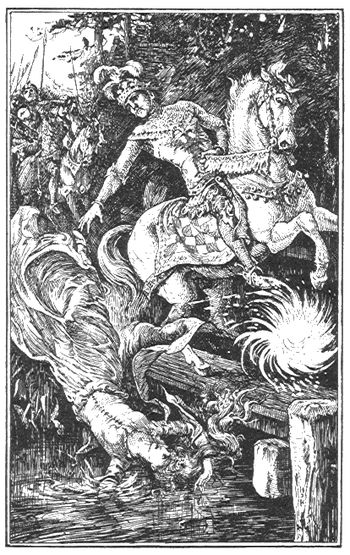

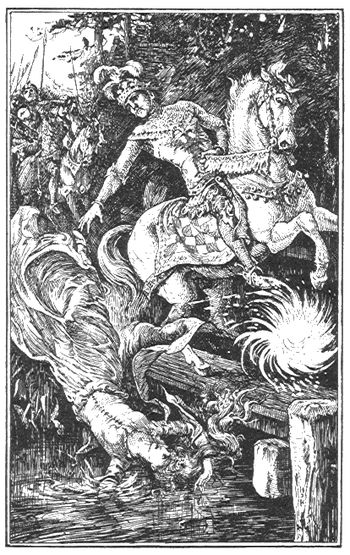

As the ninth night drew near she became very unhappy, for she feared lest some terrible mischance should arise and ruin all. On this night she crept quietly out of the house and waited trembling at some little distance from the hut. Presently she heard the muffled tramp of horses, and soon the armed troop appeared, led by the Prince, who had prudently marked all the trees beforehand, in order to know the way. When he saw the maiden he sprang from his horse, lifted her into the saddle, and then, mounting behind, rode homeward. The moon shone so brightly that they had no difficulty in seeing the marked trees.

By and by the coming of dawn loosened the tongues of all the birds, and, had the Prince only known what they were saying, or the maiden been listening, they might have been spared much sorrow, but they were thinking only of each other, and when they came out of the forest the sun was high in the heavens.

Next morning, when the youngest girl did not come to her work, the old woman asked where she was. The sisters pretended not to know, but the old woman easily guessed what had happened, and, as she was in reality a wicked witch, determined to punish the fugitives. Accordingly, she collected nine different kinds of enchanters' nightshade, added some salt, which she first bewitched, and, doing all up in a cloth into the shape of a fluffy ball, sent it after them on the wings of the wind, saying:

"Whirlwind!—mother of the wind! Lend thy aid 'gainst her who sinned! Carry with thee this magic ball. Cast her from his arms for ever, Bury her in the rippling river."

At midday the Prince and his men came to a deep river, spanned by so narrow a bridge that only one rider could cross at a time. The horse on which the Prince and the maiden were riding had just reached the middle when the magic ball flew by. The horse in its fright suddenly reared, and before anyone could stop it flung the maiden into the swift current below.

The Prince tried to jump in after her, but his men held him back, and in spite of his struggles led him home, where for six weeks he shut himself up in a secret chamber, and would neither eat nor drink, so great was his grief. At last he became so ill his life was despaired of, and in great alarm the King caused all the wizards of his country to be summoned. But none could cure him. At last the wind wizard's son said to the King: "Send for the old wizard from Finland he knows more than all the wizards of your kingdom put together." A messenger was at once sent to Finland, and a week later the old wizard himself arrived on the wings of the wind. "Honored King," said the wizard, "the wind has blown this illness upon your son, and a magic ball has snatched away his beloved. This it is which makes him grieve so constantly. Let the wind blow upon him that it may blow away his sorrow." Then the King made his son go out into the wind, and he gradually recovered and told his father all. "Forget the maiden," said the King, "and take another bride"; but the Prince said he could never love another.

A year afterward he came suddenly upon the bridge where his beloved met her death. As he recalled the misfortune he wept bitterly, and would have given all he possessed to have her once more alive. In the midst of his grief he thought he heard a voice singing, and looked round, but could see no one. Then he heard the voice again, and it said:

"Alas! bewitched and all forsaken, 'Tis I must lie for ever here! My beloved no thought has taken To free his bride, that was so dear."

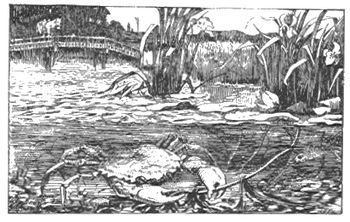

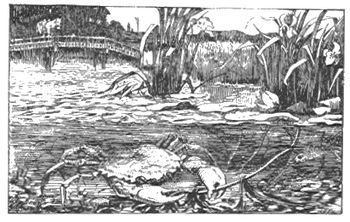

He was greatly astonished, sprang from his horse, and looked everywhere to see if no one were hidden under the bridge; but no one was there. Then he noticed a yellow water-lily floating on the surface of the water, half hidden by its broad leaves; but flowers do not sing, and in great surprise he waited, hoping to hear more.

Then again the voice sang:

The Prince suddenly remembered the gold-spinners, and said to himself: "If I ride thither, who knows but that they could explain this to me?" He at once rode to the hut, and found the two maidens at the fountain. He told them what had befallen their sister the year before, and how he had twice heard a strange song, but yet could see no singer. They said that the yellow water-lily could be none other than their sister, who was not dead, but transformed by the magic ball. Before he went to bed, the eldest made a cake of magic herbs, which she gave him to eat. In the night he dreamed that he was living in the forest and could understand all that the birds said to each other. Next morning he told this to the maidens, and they said that the charmed cake had caused it, and advised him to listen well to the birds, and see what they could tell him, and when he had recovered his bride they begged him to return and deliver them from their wretched bondage."Alas! bewitched and all forsaken, 'Tis I must lie for ever here! My beloved no thought has taken To free his bride, that was so dear."

Having promised this, he joyfully returned home, and as he was riding through the forest he could perfectly understand all that the birds said. He heard a thrush say to a magpie: "How stupid men are! they cannot understand the simplest thing. It is now quite a year since the maiden was transformed into a water-lily, and, though she sings so sadly that anyone going over the bridge must hear her, yet no one comes to her aid. Her former bridegroom rode over it a few days ago and heard her singing, but was no wiser than the rest."

"And he is to blame for all her misfortunes," added the magpie. "If he heeds only the words of men she will remain a flower for ever. She were soon delivered were the matter only laid before the old wizard of Finland."

After hearing this, the Prince wondered how he could get a message conveyed to Finland. He heard one swallow say to another: "Come, let us fly to Finland; we can build better nests there."

"Stop, kind friends!" cried the Prince. "Will you do something for me?" The birds consented, and he said: "Take a thousand greetings from me to the wizard of Finland, and ask him how I may restore a maiden transformed into a flower to her own form."

The swallows flew away, and the Prince rode on to the bridge. There he waited, hoping to hear the song. But he heard nothing but the rushing of the water and the moaning of the wind, and, disappointed, rode home.

Shortly after, he was sitting in the garden, thinking that the swallows must have forgotten his message, when he saw an eagle flying above him. The bird gradually descended until it perched on a tree close to the Prince and said: "The wizard of Finland greets thee and bids me say that thou mayst free the maiden thus: Go to the river and smear thyself all over with mud; then say: 'From a man into a crab,' and thou wilt become a crab. Plunge boldly into the water, swim as close as thou canst to the water-lily's roots, and loosen them from the mud and reeds. This done, fasten thy claws into the roots and rise with them to the surface. Let the water flow all over the flower, and drift with the current until thou comest to a mountain ash tree on the left bank. There is near it a large stone. Stop there and say: 'From a crab into a man, from a water-lily into a maiden,' and ye both will be restored to your own forms."

Full of doubt and fear, the Prince let some time pass before he was bold enough to attempt to rescue the maiden. Then a crow said to him: "Why dost thou hesitate? The old wizard has not told thee wrong, neither have the birds deceived thee; hasten and dry the maiden's tears."

"Nothing worse than death can befall me," thought the Prince, "and death is better than endless sorrow." So he mounted his horse and went to the bridge. Again he heard the water-lily's lament, and, hesitating no longer, smeared himself all over with mud, and, saying: "From a man into a crab," plunged into the river. For one moment the water hissed in his ears, and then all was silent. He swam up to the plant and began to loosen its roots, but so firmly were they fixed in the mud and reeds that this took him a long time.

He then grasped them and rose to the surface, letting the water flow over the flower. The current carried them down the stream, but nowhere could he see the mountain ash. At last he saw it, and close by the large stone. Here he stopped and said: "From a crab into a man, from a water-lily into a maiden," and to his delight found himself once more a prince, and the maiden was by his side. She was ten times more beautiful than before, and wore a magnificent pale yellow robe, sparkling with jewels. She thanked him for having freed her from the cruel witch's power, and willingly consented to marry him.

But when they came to the bridge where he had left his horse it was nowhere to be seen, for, though the Prince thought he had been a crab only a few hours, he had in reality been under the water for more than ten days. While they were wondering how they should reach his father's court, they saw a splendid coach driven by six gaily caparisoned horses coming along the bank. In this they drove to the palace. The King and Queen were at church, weeping for their son, whom they had long mourned for dead. Great was their delight and astonishment when the Prince entered, leading the beautiful maiden by the hand. The wedding was at once celebrated and there was feasting and merry-making throughout the kingdom for six weeks.

Some time afterward the Prince and his bride were sitting in the garden, when a crow said to them: "Ungrateful creatures! Have you forgotten the two poor maidens who helped you in your distress? Must they spin gold flax for ever? Have no pity on the old witch. The three maidens are princesses, whom she stole away when they were children together, with all the silver utensils, which she turned into gold flax. Poison were her fittest punishment."

The Prince was ashamed of having forgotten his promise and set out at once, and by great good fortune reached the hut when the old woman was away. The maidens had dreamed that he was coming, and were ready to go with him, but first they made a cake in which they put poison, and left it on a table where the old woman was likely to see it when she returned. She did see it, and thought it looked so tempting that she greedily ate it up and at once died.

In the secret chamber were found fifty wagon-loads of gold flax, and as much more was discovered buried. The hut was razed to the ground, and the Prince and his bride and her two sisters lived happily ever after.

Unknown.

La ninfea. Le filatrici d’oro

Una volta in una grande foresta vivevano una vecchia e tre ragazze. Erano tutte e tre stupende, ma la più giovane era la più bella. La loro capanna era completamente nascosta dagli alberi e nessuno vedeva la loro bellezza se non il sole di giorno e la luna di notte, e gli occhi delle stelle. La vecchia faceva lavorare duramente le ragazze, dal mattino alla sera, filando il lino d’oro in matasse di filo, e quando una rocca era piena, ne veniva data loro un’altra, così non avevano riposo. Il filo doveva essere sottile e uniforme, e quando era terminato, veniva chiuso in una stanza segreta dalla vecchia, la quale faceva un viaggio due o tre volte ogni estate. Prima di partire, distribuiva il lavoro per ogni giorno della sua assenza e tornava sempre di notte, così le ragazze non vedevano mai cosa portasse indietro con sé, né lei diceva loro da dove venisse il lino d’oro né a che cosa servisse.

Dunque quando venne il momento per la donna di fare un altro dei suoi viaggi, dette a ciascuna ragazza lavoro per sei giorni, con il solito avvertimento: “Bambine, non distraevi e non parlate per nessun motivo a un uomo perché, se lo farete, il vostro filo perderà la sua lucentezza e ogni genere di disgrazia vi perseguiterà.” Loro ridevano di questi ripetuti avvertimenti, dicendosi l’una con l’altra: “Come può il nostro oro perdere lucentezza e come possiamo avere la possibilità di parlare con un uomo?”

Il terzo giorno dopo la partenza della vecchia un giovane principe, che stava cacciando nella foresta, si separò dai suoi compagni e si perse completamente. Stanco di cercare la strada, si lasciò cadere sotto un albero, lasciando che il cavallo pascolasse a proprio piacere, e si addormentò.

Il sole era sorto quando si svegliò e cominciò ancora una volta a tentare di ritrovare la strada per uscire dalla foresta. Alla fine si accorse di uno stretto sentiero che seguì con impazienza e scoprì che lo conduceva davanti a una piccola capanna. Le ragazze, che erano sedute sulla porta della capanna a godersi la frescura, lo videro avvicinarsi e le due più grandi si spaventarono molto perché rammentavano l’avvertimento della vecchia, ma la più giovane disse: “Non ho mai visto prima uno come lui, lasciatemi dare un’occhiata.” La implorarono di rientrare, ma, vedendo che non voleva, la lasciarono e il Principe, avvicinandosi, salutò cortesemente la ragazza e le disse di aver perso la strada nella foresta e di essere affamato e stanco.

Lei gli mise davanti il cibo e fu così deliziata dai suoi discorsi che dimenticò l’ammonimento della vecchia e indugiò per ore. Nel frattempo i compagni del Principe lo avevano cercato invano in lungo e in largo, così mandarono due messaggeri a riferire la triste notizia al Re, il quale ordinò immediatamente che un reggimento di cavalleria e uno di fanteria andassero a cercarlo.

Dopo tre giorni di ricerca, trovarono la capanna. Il Principe era ancora seduto sulla soglia e sembrava così felice in compagnia della ragazza che gli era sembrato fosse trascorsa solo un’ora. Prima di partire, promise di ritornare e portarla alla corte di suo padre, dove avrebbe fatto di lei la sua sposa. Quando se ne fu andato, la ragazza sedette al filatoio per recuperare il tempo perduto, ma con sgomento scoprì che il filo aveva perduto la propria brillantezza. Il suo cuore accelerò i battiti e pianse amaramente perché aveva rammentato l’avvertimento della vecchia e non sapeva che genere di disgrazie si sarebbero abbattute su di lei.

La vecchia tornò di notte e capì dal filo opaco che cosa fosse accaduto durante la sua assenza. Si arrabbiò terribilmente e disse alla ragazza che aveva attirato l’infelicità su di sé e sul principe. La ragazza non si dava pace pensando a ciò. Alla fine non poté sopportarlo più a lungo e decise di cercare aiuto dal Principe.

Sin da bambina aveva imparato a comprendere il linguaggio degli uccelli e adesso le era di grande utilità perché, vedendo un corvo lisciarsi le piume su un ramo di pino, gli disse sommessamente. “Caro uccello, il più intelligente di tutti gli uccelli, e anche il più veloce in volo, vorresti aiutarmi?” “Come ti posso aiutare?” chiese il corvo. Lei rispose: “Vola via, fino a raggiungere una città in cui c’è il palazzo del re; cerca il figlio del re e digli della grande disgrazia che mi è capitata.” Così disse al corvo di come il filo avesse perso la lucentezza, di quanto terribilmente fosse arrabbiata la vecchia e di come temesse un grande disastro. Il corvo promise lealmente di fare ciò che chiedeva e, spiegando le ali, volò via. La ragazza andò a casa e lavorò duramente tutto il giorno avvolgendo il filo che la sorella maggiore aveva filato perché la vecchia non aveva più voluto lasciarla filare. Verso sera sentì il gracchiare del corvo dal pino e si affrettò laggiù ansiosamente a sentire la risposta.

Per fortuna il corvo aveva trovato un figlio del mago del vento nel giardino del palazzo, il quale comprendeva il linguaggio degli uccelli, e gli aveva affidato il messaggio. Quando il Principe lo sentì, fu assai addolorato e chiese consiglio agli amici su come liberare la ragazza. Poi disse al figlio del mago del vento: “Prega il corvo di volare rapidamente indietro dalla ragazza e di dirle di stare pronta la nona notte perché allora andrò a prenderla e la porterò via.” Il figlio del mago del vento lo fece e il corvo volò così rapidamente che raggiunse la capanna quella sera stessa. La ragazza ringraziò di tutto cuore l’uccello e tornò a casa, senza dire a nessuno ciò che aveva udito.

Mentre si avvicinava la nona notte, cominciò a essere molto infelice perché temeva potesse accadere qualche terribile disgrazia che rovinasse tutto. La notte stabilita sgusciò silenziosamente fuori di casa e attese tremando a una certa distanza dalla capanna. Di lì a poco sentì il passo attutito dei cavalli e ben presto apparvero le truppe, condotte dal principe il quale prudentemente aveva segnato in anticipo tutti gli alberi per trovare la strada. Quando vide la ragazza, balzò dal cavallo, la fece salire in sella e poi, montando dietro, galoppò verso casa. La luna risplendeva così chiaramente che non ebbero difficoltà a vedere i segni tracciati.

Ben presto l’arrivo dell’alba sciolse le lingue di tutti gli uccelli e, se solo il Principe avesse compreso ciò che stavano dicendo o la ragazza li avesse ascoltati, si sarebbero risparmiati molta pena, ma pensavano solo l’uno all’altra e quando uscirono dalla foresta, il sole era alto nel cielo.

Il mattino seguente, quando la ragazza più giovane non si presentò a lavorare, la vecchia chiese dove fosse. Le sorelle finsero di non saperlo, ma la vecchia intuì facilmente ciò che era accaduto e, siccome in realtà era una perfida strega, decise di punire i fuggitivi. Di conseguenza raccolse nove diversi tipi belladonna degli stregoni, aggiunse un po’ di sale che prima aveva stregato e, mettendo tutto in un panno al quale diede forma di una soffice palla, la mandò dietro di loro sulle ali del vento, dicendo:

”Mulinello! Madre del vento! Dammi il tuo aiuto contro colei che ha peccato! Porta con te questa palla magica. Strappala per sempre dalle braccia di lui, seppelliscila nel fiume gorgogliante.”

A mezzogiorno il Principe e i suoi uomini giunsero presso un profondo fiume, attraversato da un ponte così stretto che vi poteva passare un solo cavaliere alla volta. Il cavallo sul quale stavano cavalcando il principe e la ragazza era appena arrivato nel mezzo quando la palla magica volò lì. Il cavallo si impennò spaventato e, prima che qualcuno potesse fermarlo, scaraventò la ragazza nella ripida corrente sottostante.

Il principe tentò di saltare dietro di lei, ma i suoi uomini lo trattennero e, nonostante i suoi sforzi, lo condussero a casa, dove per sei settimane si chiuse in una stanza segreta senza mangiare né bere, tanto grande era il suo dolore. Alla fine si ammalò tanto per la disperazione e con gran paura il re fece convocare tutti i maghi del paese. Ma nessuno poteva curare il Principe. Alla fine il figlio del mago del vento disse al Re: “Chiamate il vecchio mago dalla Finlandia, egli ne sa più di tutti i maghi del paese messi insieme.” Fu mandato subito un messaggero in Finlandia e una settimana più tardi il vecchio mago in persona arrivò sulle ali del vento. Il mago disse. “Onorato sovrano, il vento ha soffiato questa malattia su tuo figlio e una palla magica ha portato via la sua amata. È ciò che lo rende così costantemente afflitto. Lascia che il vento soffi su di lui in modo tale da portar via il suo dolore.” Allora il Re mandò fuori nel vento il figlio ed egli gradatamente si riprese e raccontò tutto a suo padre. “Dimentica quella ragazza,” disse il Re, “e prendi un’altra sposa.”; ma il principe disse che non avrebbe amato mai nessun altra.

Un anno più tardi giunse improvvisamente presso il ponte sul quale la sua amata aveva trovato la morte. Rammentando quell’evento sciagurato, pianse amaramente e avrebbe dato tutto ciò che possedeva per averla di nuovo viva. Nel pieno del suo dolore pensò di sentire una voce che cantava e si guardò attorno, ma non poté vedere nessuno. Allora udì di nuovo la voce che diceva:

”Ahimè! Stregata e abbandonata da tutti, devo giacere per sempre qui! Il mio amato non si da pensiero di liberare la sua sposa, che era cosi cara.”

Egli fu assai stupito, balzò da cavallo e guardò dappertutto per vedere se qualcuno fosse nascosto sotto il ponte, ma lì non c’era nessuno. Allora si accorse di una ninfea gialla che galleggiava sulla superficie dell’acqua, mezzo nascosta dalle ampie foglie, ma i fiori non cantano, e con sua grande sorpresa aspettò, sperando di sentire altro.

Di nuovo la voce cantò:

”Ahimè! Ahimè! Stregata e abbandonata da tutti, devo giacere per sempre qui! Il mio amato non si da pensiero di liberare la sua sposa, che era cosi cara.”

Il Principe si rammentò improvvisamente delle filatrici d’oro e si disse. ‘Se cavalco fin laggiù, chissà che non possano darmi una spiegazione?’ E subito cavalcò verso la capanna e trovò le due ragazze alla fontana. Raccontò loro ciò che era accaduto alla sorella l’anno precedente e come avesse sentito per due volte una strana canzone, ma senza vedere nessuno che cantasse. Esse gli dissero che la ninfea gialla non poteva essere altri che la loro sorella, la quale non era morta, ma era stata trasformata dalla palla magica. Prima di andare a dormire, la maggiore fece una torta di erbe magiche che gli diede da mangiare. La notte lui sognò che stava vivendo nella foresta e poteva comprendere tutto ciò che gli uccelli si dicevano l’un l’altro. Il mattino seguente lo disse alle ragazze e loro risposero che era stata la torta magica a provocare ciò, e lo avvertirono di ascoltare bene gli uccelli, e vedere che cosa gli avrebbero detto, e quando avesse ritrovato la sua sposa, lo pregarono di tornare e liberarle da quella miserabile schiavitù.

Dopo averlo promesso, il principe tornò a casa pieno di gioia e, mentre cavalcava nella foresta, poté comprendere perfettamente ciò che dicevano gli uccelli. Sentì un tordo dire a una gazza: “Quanto sono stupidi gli uomini! Non possono capire le cose più semplici. È trascorso quasi un anno da quando la ragazza è stata trasformata in una ninfea e, sebbene canti così tristemente che chiunque passi sul ponte la possa sentire, nemmeno uno viene in suo aiuto. Il suo precedente promesso sposo è passato a cavallo pochi giorni fa e l’ha sentita che cantava, eppure non è stato più saggi degli altri.”

”E lui è da biasimare per tutte le disgrazie della ragazza,” aggiunse la gazza, “se baderà solo alle parole degli uomini, lei resterà un fiore per sempre. Lei sarebbe presto liberata se solo si potesse esporre il caso al vecchio mago della Finlandia.”

Dopo aver udito ciò, il Principe si domandò come avrebbe potuto mandare un messaggio da consegnare in Finlandia. Sentì una rondine dire a un’altra: “Vieni, voliamo in Finlandia, là potremo costruire nidi migliori.”

”Fermatevi, gentili amiche!” gridò il Principe. “Fareste qualcosa per me?” Gli uccelli acconsentirono e lui disse: “Portate tutti i miei saluti al mago della Finlandia e chiedetegli come io possa restituire il suo aspetto a una ragazza trasformata in un fiore.”

Le rondini volarono via e il Principe galoppò fino al ponte. Lì attese, sperando di udire la canzone. Ma non senti niente altro che lo sciabordio dell’acqua e il mormorio del vento, così, deluso, cavalcò verso casa.

Poco dopo era seduto in giardino, pensando che le rondini dovessero aver dimenticato il suo messaggio, quando vide un’aquila che volava verso di lui. L’uccello discese gradatamente finché si posò su un albero vicino al Principe e disse: “Il mago della Finlandia ti saluta e mi incarica di dirti che puoi liberare così la ragazza: vai al fiume e cospargiti di fango, poi di’’Da uomo a granchio’ e diventerai un granchio. Immergiti con decisione nell’acqua, nuota più vicino che puoi alle radici della ninfea e liberare dal fango e dal canneto. Fatto ciò, afferra con le chele le radici e sali in superficie con esse. Lascia che tutta l’acqua scorra via dal fiore e lasciati trascinare dalla corrente finché giungerai a un albero di sorbo sulla riva sinistra. Lì vicino c’è una grossa pietra. Fermati lì e di’: ‘Da granchio a uomo, da ninfea a ragazza’ e entrambi riacquisterete il vostro aspetto.”

Pieno di dubbi e di timori, il Principe lasciò passare un po’ di tempo prima di sentirsi abbastanza coraggioso per tentare di salvare la ragazza. Allora una cornacchia gli disse: “Perché esiti? Il vecchio mago non ti ha detto il falso, né gli uccelli ti hanno ingannato; affrettati ad asciugare le lacrime della ragazza.”

’Non potrà capitarmi nulla di peggio della morte,’pensò il Principe, ‘e la morte è meglio del dolore infinito.’ Così salì a cavallo e andò al ponte. Di nuovo sentì il lamento della ninfea e, senza esitare più a lungo, si cosparse di fango e, dicendo: ‘Da uomo a granchio’ si tuffò nel fiume. Per un attimo l’acqua gli sibilò nelle orecchie e poi tutto fu silenzio. Nuotò verso la pianta e cominciò a allentare le radici, erano fissate così saldamente nel fango e tra le canne che ciò richiese parecchio tempo.

Poi le afferrò e risalì in superficie, lasciando scolare l’acqua dal fiore. La corrente li trasportò lungo il corso d’acqua, ma non poteva vedere un sorbo da nessuna parte. Infine lo vide, e lì vicino la grossa pietra. Si fermò lì e disse. “Da granchi a uomo, da ninfea a ragazza.” E con sua gioia scoprì di essere di nuovo un principe e che la ragazza era al suo fianco. Era dieci volte più bella di prima e indossava una magnifica veste giallo tenue, scintillante di gioielli. Lo ringraziò per averla liberata dal potere della crudele strega e acconsentì volentieri a sposarlo.

Quando tornarono al ponte, sul quale aveva lasciato il cavallo, questo non si vedeva da nessuna parte perché, sebbene il principe pensasse di essere stato un granchio solo per poche ore, in realtà era stato sott’acqua per più di dieci giorni. Mentre si stavano chiedendo come avrebbero potuto raggiungere la corte del re, videro venire lungo la riva una splendida carrozza trainata da sei cavalli vivacemente bardati. Con questa furono condotti a palazzo. Il Re e la Regina era in chiesa, a piangere per il figlio, della cui morte si affliggevano da tempo. Grandi furono la loro gioia e il loro stupore quando il Principe entrò, tenendo per mano la bellissima ragazza. Le nozze furono celebrate subito e ci furono festeggiamenti e baldoria in tutto il regno per sei mesi.

Un po’ di tempo dopo il principe e la sua sposa erano seduti in giardino quando giunse un corvo e disse loro: “Creature ingrate! Avete dimenticato le due povere ragazze che vi hanno aiutati nella difficoltà? Dovranno filare oro per sempre? Nessuna pietà per la vecchia strega. Le tre ragazze sono principesse rapite insieme da bambine, con tutti i loro arnesi d’argento che lei ha trasformato in lino d’oro. Il veleno sarebbe la punizione più appropriata.”

Il Principe si vergognò di aver dimenticato la promessa e partì subito; con grande fortuna giunse alla capanna quando la vecchia era lontana. Le ragazze avevano sognato che tornasse ed erano pronte ad andare via con lui, ma prima fecero una torta nella quale misero il veleno e la lasciarono sul tavolo, dove la vecchia l’avrebbe probabilmente vista quando fosse tornata. La vide, e le sembrò così invitante che la mangiò avidamente e morì subito.

Nella stanza segreta furono trovati cinquanta carri di lino d’oro e altrettanto fu scoperto sepolto. La capanna fu rasa al suolo e il principe con la sposa e le sue due sorelle vissero per sempre felici e contenti.

Origine sconosciut. Andrew Lang non la riporta, ma probabilmente l'origine è estone.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)