There was, once upon a time, a man and his wife fagot-makers by trade, who had several children, all boys. The eldest was but ten years old, and the youngest only seven.

They were very poor, and their seven children incommoded them greatly, because not one of them was able to earn his bread. That which gave them yet more uneasiness was that the youngest was of a very puny constitution, and scarce ever spoke a word, which made them take that for stupidity which was a sign of good sense. He was very little, and when born no bigger than one’s thumb, which made him be called Little Thumb.

The poor child bore the blame of whatsoever was done amiss in the house, and, guilty or not, was always in the wrong; he was, notwithstanding, more cunning and had a far greater share of wisdom than all his brothers put together; and, if he spake little, he heard and thought the more.

There happened now to come a very bad year, and the famine was so great that these poor people resolved to rid themselves of their children. One evening, when they were all in bed and the fagot-maker was sitting with his wife at the fire, he said to her, with his heart ready to burst with grief:

“Thou seest plainly that we are not able to keep our children, and I cannot see them starve to death before my face; I am resolved to lose them in the wood to-morrow, which may very easily be done; for, while they are busy in tying up fagots, we may run away, and leave them, without their taking any notice.”

“Ah!” cried his wife; “and canst thou thyself have the heart to take thy children out along with thee on purpose to lose them?”

In vain did her husband represent to her their extreme poverty: she would not consent to it; she was indeed poor, but she was their mother. However, having considered what a grief it would be to her to see them perish with hunger, she at last consented, and went to bed all in tears.

Little Thumb heard every word that had been spoken; for observing, as he lay in his bed, that they were talking very busily, he got up softly, and hid himself under his father’s stool, that he might hear what they said without being seen. He went to bed again, but did not sleep a wink all the rest of the night, thinking on what he had to do. He got up early in the morning, and went to the river-side, where he filled his pockets full of small white pebbles, and then returned home.

They all went abroad, but Little Thumb never told his brothers one syllable of what he knew. They went into a very thick forest, where they could not see one another at ten paces distance. The fagot-maker began to cut wood, and the children to gather up the sticks to make fagots. Their father and mother, seeing them busy at their work, got away from them insensibly, and ran away from them all at once, along a by-way through the winding bushes.

When the children saw they were left alone, they began to cry as loud as they could. Little Thumb let them cry on, knowing very well how to get home again, for, as he came, he took care to drop all along the way the little white pebbles he had in his pockets. Then he said to them:

“Be not afraid, brothers; father and mother have left us here, but I will lead you home again, only follow me.”

They did so, and he brought them home by the very same way they came into the forest. They dared not go in, but sat themselves down at the door, listening to what their father and mother were saying.

The very moment the fagot-maker and his wife reached home, the lord of the manor sent them ten crowns, which he had owed them a long while, and which they never expected. This gave them new life, for the poor people were almost famished. The fagot-maker sent his wife immediately to the butcher’s. As it was a long while since they had eaten a bit, she bought thrice as much meat as would sup two people. When they had eaten, the woman said:

“Alas! where are now our poor children? they would make a good feast of what we have left here; but it was you, William, who had a mind to lose them: I told you we should repent of it. What are they now doing in the forest? Alas! dear God, the wolves have perhaps already eaten them up; thou art very inhuman thus to have lost thy children.”

The fagot-maker grew at last quite out of patience, for she repeated it above twenty times, that they should repent of it, and that she was in the right of it for so saying. He threatened to beat her if she did not hold her tongue. It was not that the fagot-maker was not, perhaps, more vexed than his wife, but that she teased him, and that he was of the humor of a great many others, who love wives to speak well, but think those very importunate who are continually doing so. She was half-drowned in tears, crying out:

“Alas! where are now my children, my poor children?”

She spoke this so very loud that the children, who were at the gate, began to cry out all together:

“Here we are! Here we are!”

She ran immediately to open the door, and said, hugging them:

“I am glad to see you, my dear children; you are very hungry and weary; and my poor Peter, thou art horribly bemired; come in and let me clean thee.”

Now, you must know that Peter was her eldest son, whom she loved above all the rest, because he was somewhat carroty, as she herself was. They sat down to supper, and ate with such a good appetite as pleased both father and mother, whom they acquainted how frightened they were in the forest, speaking almost always all together. The good folks were extremely glad to see their children once more at home, and this joy continued while the ten crowns lasted; but, when the money was all gone, they fell again into their former uneasiness, and resolved to lose them again; and, that they might be the surer of doing it, to carry them to a much greater distance than before.

They could not talk of this so secretly but they were overheard by Little Thumb, who made account to get out of this difficulty as well as the former; but, though he got up very early in the morning to go and pick up some little pebbles, he was disappointed, for he found the house-door double-locked, and was at a stand what to do. When their father had given each of them a piece of bread for their breakfast, Little Thumb fancied he might make use of this instead of the pebbles by throwing it in little bits all along the way they should pass; and so he put the bread in his pocket.

Their father and mother brought them into the thickest and most obscure part of the forest, when, stealing away into a by-path, they there left them. Little Thumb was not very uneasy at it, for he thought he could easily find the way again by means of his bread, which he had scattered all along as he came; but he was very much surprised when he could not find so much as one crumb; the birds had come and had eaten it up, every bit. They were now in great affliction, for the farther they went the more they were out of their way, and were more and more bewildered in the forest.

Night now came on, and there arose a terribly high wind, which made them dreadfully afraid. They fancied they heard on every side of them the howling of wolves coming to eat them up. They scarce dared to speak or turn their heads. After this, it rained very hard, which wetted them to the skin; their feet slipped at every step they took, and they fell into the mire, whence they got up in a very dirty pickle; their hands were quite benumbed.

Little Thumb climbed up to the top of a tree, to see if he could discover anything; and having turned his head about on every side, he saw at last a glimmering light, like that of a candle, but a long way from the forest. He came down, and, when upon the ground, he could see it no more, which grieved him sadly. However, having walked for some time with his brothers toward that side on which he had seen the light, he perceived it again as he came out of the wood.

They came at last to the house where this candle was, not without an abundance of fear: for very often they lost sight of it, which happened every time they came into a bottom. They knocked at the door, and a good woman came and opened it; she asked them what they would have.

Little Thumb told her they were poor children who had been lost in the forest, and desired to lodge there for God’s sake.

The woman, seeing them so very pretty, began to weep, and said to them:

“Alas! poor babies; whither are ye come? Do ye know that this house belongs to a cruel ogre who eats up little children?”

“Ah! dear madam,” answered Little Thumb (who trembled every joint of him, as well as his brothers), “what shall we do? To be sure the wolves of the forest will devour us to-night if you refuse us to lie here; and so we would rather the gentleman should eat us; and perhaps he may take pity upon us, especially if you please to beg it of him.”

The Ogre’s wife, who believed she could conceal them from her husband till morning, let them come in, and brought them to warm themselves at a very good fire; for there was a whole sheep upon the spit, roasting for the Ogre’s supper.

As they began to be a little warm they heard three or four great raps at the door; this was the Ogre, who had come home. Upon this she hid them under the bed and went to open the door. The Ogre presently asked if supper was ready and the wine drawn, and then sat himself down to table. The sheep was as yet all raw and bloody; but he liked it the better for that. He sniffed about to the right and left, saying:

“I smell fresh meat.”

“What you smell so,” said his wife, “must be the calf which I have just now killed and flayed.”

“I smell fresh meat, I tell thee once more,” replied the Ogre, looking crossly at his wife; “and there is something here which I do not understand.”

As he spoke these words he got up from the table and went directly to the bed.

“Ah, ah!” said he; “I see then how thou wouldst cheat me, thou cursed woman; I know not why I do not eat thee up too, but it is well for thee that thou art a tough old carrion. Here is good game, which comes very quickly to entertain three ogres of my acquaintance who are to pay me a visit in a day or two.”

With that he dragged them out from under the bed one by one. The poor children fell upon their knees, and begged his pardon; but they had to do with one of the most cruel ogres in the world, who, far from having any pity on them, had already devoured them with his eyes, and told his wife they would be delicate eating when tossed up with good savory sauce. He then took a great knife, and, coming up to these poor children, whetted it upon a great whet-stone which he held in his left hand. He had already taken hold of one of them when his wife said to him:

“Why need you do it now? Is it not time enough to-morrow?”

“Hold your prating,” said the Ogre; “they will eat the tenderer.

“But you have so much meat already,” replied his wife, “you have no occasion; here are a calf, two sheep, and half a hog.”

“That is true,” said the Ogre; “give them their belly full that they may not fall away, and put them to bed.”

The good woman was overjoyed at this, and gave them a good supper; but they were so much afraid they could not eat a bit. As for the Ogre, he sat down again to drink, being highly pleased that he had got wherewithal to treat his friends. He drank a dozen glasses more than ordinary, which got up into his head and obliged him to go to bed.

The Ogre had seven daughters, all little children, and these young ogresses had all of them very fine complexions, because they used to eat fresh meat like their father; but they had little gray eyes, quite round, hooked noses, and very long sharp teeth, standing at a good distance from each other. They were not as yet over and above mischievous, but they promised very fair for it, for they had already bitten little children, that they might suck their blood.

They had been put to bed early, with every one a crown of gold upon her head. There was in the same chamber a bed of the like bigness, and it was into this bed the Ogre’s wife put the seven little boys, after which she went to bed to her husband.

Little Thumb, who had observed that the Ogre’s daughters had crowns of gold upon their heads, and was afraid lest the Ogre should repent his not killing them, got up about midnight, and, taking his brothers’ bonnets and his own, went very softly and put them upon the heads of the seven little ogresses, after having taken off their crowns of gold, which he put upon his own head and his brothers’, that the Ogre might take them for his daughters, and his daughters for the little boys whom he wanted to kill.

All this succeeded according to his desire; for, the Ogre waking about midnight, and sorry that he deferred to do that till morning which he might have done over-night, threw himself hastily out of bed, and, taking his great knife,

“Let us see,” said he, “how our little rogues do, and not make two jobs of the matter.”

He then went up, groping all the way, into his daughters’ chamber, and, coming to the bed where the little boys lay, and who were every soul of them fast asleep, except Little Thumb, who was terribly afraid when he found the Ogre fumbling about his head, as he had done about his brothers’, the Ogre, feeling the golden crowns, said:

“I should have made a fine piece of work of it, truly; I find I drank too much last night.”

Then he went to the bed where the girls lay; and, having found the boys’ little bonnets, “Ah!” said he, “my merry lads, are you there? Let us work as we ought.”

And saying these words, without more ado, he cut the throats of all his seven daughters.

Well pleased with what he had done, he went to bed again to his wife. So soon as Little Thumb heard the Ogre snore, he waked his brothers, and bade them all put on their clothes presently and follow him. They stole down softly into the garden, and got over the wall. They kept running about all night, and trembled all the while, without knowing which way they went.

The Ogre, when he awoke, said to his wife: “Go upstairs and dress those young rascals who came here last night.”

The wife was very much surprised at this goodness of her husband, not dreaming after what manner she should dress them; but, thinking that he had ordered her to go and put on their clothes, she went up, and was strangely astonished when she perceived her seven daughters killed, and weltering in their blood.

She fainted away, for this is the first expedient almost all women find in such cases. The Ogre, fearing his wife would be too long in doing what he had ordered, went up himself to help her. He was no less amazed than his wife at this frightful spectacle.

“Ah! what have I done?” cried he. “The wretches shall pay for it, and that instantly.”

He threw a pitcher of water upon his wife’s face, and, having brought her to herself, said: “Give me quickly my boots of seven leagues, that I may go and catch them.”

He went out, and, having run over a vast deal of ground, both on this side and that, he came at last into the very road where the poor children were, and not above a hundred paces from their father’s house. They espied the Ogre, who went at one step from mountain to mountain, and over rivers as easily as the narrowest kennels. Little Thumb, seeing a hollow rock near the place where they were, made his brothers hide themselves in it, and crowded into it himself, minding always what would become of the Ogre.

The Ogre, who found himself much tired with his long and fruitless journey (for these boots of seven leagues greatly fatigued the wearer), had a great mind to rest himself, and, by chance, went to sit down upon the rock where the little boys had hid themselves.

As it was impossible he could be more weary than he was, he fell asleep, and, after reposing himself some time, began to snore so frightfully that the poor children were no less afraid of him than when he held up his great knife and was going to cut their throats. Little Thumb was not so much frightened as his brothers, and told them that they should run away immediately toward home while the Ogre was asleep so soundly, and that they should not be in any pain about him. They took his advice, and got home presently. Little Thumb came up to the Ogre, pulled off his boots gently and put them on his own legs. The boots were very long and large, but, as they were fairies, they had the gift of becoming big and little, according to the legs of those who wore them; so that they fitted his feet and legs as well as if they had been made on purpose for him. He went immediately to the Ogre’s house, where he saw his wife crying bitterly for the loss of the Ogre’s murdered daughters.

“Your husband,” said Little Thumb, “is in very great danger, being taken by a gang of thieves, who have sworn to kill him if he does not give them all his gold and silver. The very moment they held their daggers at his throat he perceived me, and desired me to come and tell you the condition he is in, and that you should give me whatsoever he has of value, without retaining any one thing; for otherwise they will kill him without mercy; and, as his case is very pressing, he desired me to make use (you see I have them on) of his boots, that I might make the more haste and to show you that I do not impose upon you.”

The good woman, being sadly frightened, gave him all she had: for this Ogre was a very good husband, though he used to eat up little children. Little Thumb, having thus got all the Ogre’s money, came home to his father’s house, where he was received with abundance of joy.

There are many people who do not agree in this circumstance, and pretend that Little Thumb never robbed the Ogre at all, and that he only thought he might very justly, and with a safe conscience, take off his boots of seven leagues, because he made no other use of them but to run after little children. These folks affirm that they are very well assured of this, and the more as having drunk and eaten often at the fagot-maker’s house. They aver that when Little Thumb had taken off the Ogre’s boots he went to Court, where he was informed that they were very much in pain about a certain army, which was two hundred leagues off, and the success of a battle. He went, say they, to the King, and told him that, if he desired it, he would bring him news from the army before night.

The King promised him a great sum of money upon that condition. Little Thumb was as good as his word, and returned that very same night with the news; and, this first expedition causing him to be known, he got whatever he pleased, for the King paid him very well for carrying his orders to the army. After having for some time carried on the business of a messenger, and gained thereby great wealth, he went home to his father, where it was impossible to express the joy they were all in at his return. He made the whole family very easy, bought places for his father and brothers, and, by that means, settled them very handsomely in the world, and, in the meantime, made his court to perfection.

Charles Perrault

L'ariete meraviglioso

C’era una volta, al tempo in cui vivevano le fate, un re che aveva tre figlie, tutte giovani, intelligenti e belle; però la più giovane delle tre, di nome Miranda, era la più graziosa e la più amata.

Il re suo padre le regalava in un mese più abiti e gioielli di quanti ne donasse in anno alle altre; ma era così generosa che divideva tutto con le sorelle ed erano sempre tutte felici e tanto affezionate l’una all’altra quanto si poteva.

Il re aveva alcuni confinanti litigiosi i quali, stanchi di lasciarlo in pace, cominciarono a muovergli guerra così ferocemente che egli temette sarebbe stato completamente sconfitto se non si fosse sforzato di difendersi. Così radunò un grande esercito e andò a combatterli, lasciando le principesse con le governanti in un castello nel quale venivano riferite loro ogni giorno le notizie della guerra – a volte che il re aveva conquistato una città, o vinto una battaglia, e infine che aveva completamente soverchiato i nemici e inseguitili fuori dal regno, e stava tornando al castello in più in fretta possibile per vedere la cara, piccola Miranda che tanto amava.

Le tre principesse indossarono abiti di raso, che avevano fatto realizzare appositamente per questa grande occasione, uno verde, uno blu e il terzo bianco; i loro gioielli erano dei medesimi colori. La maggiore indossava smeraldi, la seconda turchesi e la più giovane diamanti, e così adornate andarono incontro al Re, intonando versi che avevano composto per le sue vittorie.

Quando egli le vide tutte così belle e allegre le abbracciò teneramente, ma a Miranda dette molti più baci che a ciascuna delle altre.

Fu subito allestito un sontuoso banchetto e il re e le figlie sedettero a tavola, e siccome egli pensava che in ogni cosa vi fosse un significato special, disse alla maggiore:

“Dimmi perché hai scelto un abito verde.”

La Principessa rispose: “Sire, avendo udito delle vostre vittorie, ho pensato che il verde potesse esprimere la mia gioia e la mia speranza per un vostro rapido ritorno.”

“Questa è un’ottima risposta,” disse il re, e continuò: “e tu, figlia mia, perché hai scelto un vestito blu?”

La principessa disse: “Per dimostrarvi, sire, di aver costantemente sperato nel vostro successo e che la vostra vista mi è gradita come quella del cielo con le stelle più splendide.”

Il re disse: “Davvero le tue sagge risposte mi sbalordiscono, e quanto a te, Miranda, che cosa ti ha fatto vestire tutta di bianco?”

Miranda rispose: “Il fatto che il bianco mi doni più di qualsiasi altro colore.”

“Che cosa?” esclamò rabbiosamente il re, “è questo tutto ciò che pensi, sciocchina?”

“Ho pensato che ve ne sareste compiaciuto con me,” disse la Principessa, “e questo è tutto.”

Il re, che l’amava, fu soddisfatto di ciò e finse persino di essere contento che lei non gli avesse detto per prima alcuna altra ragione.

Poi disse: “E ora, siccome abbiamo cenato bene e non è ancora ora di andare a letto, raccontatemi che cosa avete sognato la scorsa notte.”

La maggiore raccontò di aver sognato che lui le comprava un vestito, le cui pietre preziose e i ricami d’oro erano più luminosi del sole.

Il sogno della seconda era stato che ir Re le aveva comprato un arcolaio e una rocca così che lei potesse filare alcuni indumenti per lui.

La più giovane disse: “Ho sognato che mia sorella mezzana stava per sposarsi e il giorno delle sue nozze voi, padre, tenevate una ciotola d’oro e dicevate: ‘Vieni, Miranda, e io reggerò l’acqua in cui potrai lavarti le mani.”

Il re si arrabbiò moltissimo quando udì questo sogno e aggrottò le sopracciglia terribilmente; in effetti fece una faccia così scura che tutti capirono quanto fosse arrabbiato, e si alzò e andò a letto in gran fretta; ma non riusciva a dimenticare il sogno della figlia.

‘Che questa orgogliosa ragazza foglia fare di me uno schiavo?’ si disse. ‘Non sono sorpreso dalla sua scelta di vestirsi di raso bianco senza un pensiero per me. Non mi ritiene degno della sua considerazione! Metterò fine ben presto alle sue pretese!’

Si alzò furibondo e, sebbene non fosse ancora giorno, mandò a chiamare il capitano delle sue guardie del corpo e gli disse: “Hai udito il sogno della principessa Miranda? Ritengo che significhi qualcosa di strano contro di me quindi ti ordino di condurla nella foresta e di ucciderla; per essere certo che tu l’abbia fatto, mi dovrai portare il suo cuore e la sua lingua. Se oserai ingannarmi, sarai messo a morte!”

Il capitano delle guardie rimase assai sbalordito nell’udire questo barbaro ordine, ma non osò contraddire il re per paura di farlo infuriare ancora di più o indurlo a mandare qualcun altro, così rispose che avrebbe preso la principessa e fatto ciò che il re aveva detto. Quando andò nella sua stanza, lo fecero entrare a malapena, era così presto, ma lui disse che il re aveva mandato a chiamare Miranda e lei doveva alzarsi rapidamente e uscire; una ragazzina nera di nome Patypata sollevò il suo strascico, e la sua scimmietta e il suo cagnolino corsero davanti a lei. La scimmia si chiamava Grabugeon e il cagnolino Tintin.

Il capitano delle guardie pregò Miranda di scendere in giardino dove il re si stava godendo l’aria fresca e, quando furono là, finse di cercarlo, ma siccome non lo si trovava, disse:

“Senza dubbio sua maestà è andato a passeggiare nella foresta.” e aprì la porticina che vi conduceva e vi passarono attraverso.

A quel punto cominciò ad apparire la luce del sole e la principessa, guardando la sua guida, vide che aveva le lacrime agli occhi e sembrava troppo triste per parlare.

“Che succede?” disse nel modo più gentile. “Sembri assai dispiaciuto.” L’uomo rispose: “Ahimè, principessa, chi non sarebbe dispiaciuto, se gli fosse stato ordinato di fare una cosa tanto terribile come è accaduto a me? Il re mi ha ordinato di uccidervi qui e di portargli il vostro cuore e la vostra lingua, e se disobbedirò, perderò la vita.”

La povera principessa era terrorizzata, impallidì e cominciò a piangere sommessamente.

Guardando il capitano delle guardie con quei suoi meravigliosi occhi, disse gentilmente:

“Avresti davvero il coraggio di uccidermi? Non ti ho mai fatto alcun male e ho sempre parlato bene di te al re. Se avessi meritato la collera di mio padre, soffrirei in silenzio, ma, ahimè, lui è ingiusto nel lamentarsi di me quando io l’ho trattato sempre con amore e rispetto.”

“Non temete, principessa,” disse il capitano delle guardie, “mi ucciderei piuttosto che farvi del male; ma seppure io fossi ucciso, voi non sareste in salvo: dobbiamo trovare il modo di far credere al re che siate morta.”

“Che cosa possiamo fare?” disse Miranda; “A meno che tu non prenda il mio cuore e la mia lingua, non ti crederà mai.”

La principessa e il capitano delle guardie stavano parlando con tanto trasporto che non pensavano a Patypata, ma lei aveva ascoltato di nascosto tutto ciò che avevano detto e ora venne a gettarsi ai piedi di Miranda.

“Padrona,” disse, “ti offro la mia vita; lascia che sia uccisa io, non potrò essere che troppo felice di morire per una padrona così gentile.”

“Via, Patypata,” gridò la principessa, baciandola, “ciònon accadrà mai; la tua vita mi è preziosa quanto la mia, specialmente dopo una tale prova di affetto come quella che mi hai appena dato.”

“Avete ragione, principessa,” disse Grabugeon, facendosi avanti, “ad amare tanto una schiava fedele come Patypata; lei vi è più utile di me, vi offro assai volentieri la mia lingua e il mio cuore, specialmente perché desidero crearmi una fama nella Terra dei Folletti.”

“No, no, mia piccola Grabugeon,” rispose Miranda, “non posso tollerare il pensiero di toglierti la vita.”

“Per un buon cagnolino quale io sono,” gridò Tintin, “è impensabile lasciar morire per la padrona uno di voi due. Se qualcuno deve morire per lei, che sia io.”

E allora cominciò una gran disputa tra Patypata, Grabugeon e Tintin e giunsero alle parole grosse finché Grabugeon, che era più veloce degli altri, si arrampicò in cima all’albero più vicino e si lasciò cadere a capofitto sul terreno, dove giacque morta!

La principessa era assai dispiaciuta ma, siccome Grabugeon era proprio morta, permise al capitano di prendere la sua lingua ma, ahimè, era così piccola, non più grande del pollice della principessa, che decisero pieni di dispiacere che non serviva a nulla; il re non ci sarebbe cascato nemmeno per un momento!

“Ahimè, scimmietta mia,” esclamò la principessa, “ti ho perduta e tuttavia non sto meglio di prima.”

“L’onore di salvare la vostra vita è mio,” la interruppe Patypata e, prima che potessero impedirglielo, afferrò un coltello e in un attimo si recise la testa.

Ma quando il capitano delle guardie volle prendere la sua lingua, si rivelò essere completamente nera, così che neppure essa non avrebbe mai ingannato il re.

“Non sono sfortunata?” gridò la principessa, “ho perso tutto ciò che amo e non sto meglio di prima.”

“Se tu avessi accettato la mia offerta,” disse Tintin, “avresti avuto solo me da rimpiangere e io avrei avuto tutta la tua gratitudine.”

Miranda baciò il cagnolino, piangendo così amaramente che infine non poté sopportarlo oltre e si inoltrò nella foresta. Quando si guardò indietro, il capitano delle guardie se n’era andato e lei era sola, tranne che per la presenza di Patypata, Grabugeon e Tintin, che giacevano sul terreno. Non avrebbe potuto lasciare quel luogo finché non li avesse sepolti in una graziosa tomba ricoperta di muschio ai piedi di un albero, e scrisse i loro nomi sulla corteccia di un albero e come fossero morti tutti per salvarle la vita. Poi cominciò a pensare a dove sarebbe potuta andare per salvarsi perché quella foresta era così vicina al castello di suo padre che temeva di essere vista e riconosciuta dal primo passante e inoltre era piena di leoni e di lupi, che avrebbero fatto a pezzi una principessa tanto rapidamente come fosse un pollo selvatico. Così cominciò a camminare più in fretta che poté, ma la foresta era così vasta e il sole così caldo che quasi morì di caldo, paura e fatica; guardando la strada, le sembrava che la foresta non avesse fine ed era così spaventata che ogni istante credeva di sentire il re rincorrerla per ucciderla. Potete immaginare come si sentisse mirabile e quanto piangesse mentre camminava, non sapendo che sentiero seguire, con i cespugli spinosi che la graffiavano terribilmente e piangendo e perdendo a brandelli il bel vestito.

Infine sentì il belato di una pecora e si disse:

‘Senza dubbio qui ci sono dei pastori con le loro greggi, loro mi indicheranno la strada per un villaggio qualsiasi in cui io possa vivere travestita da contadina. Povera me! Non sempre i re e le principesse sono le persone più felici del mondo. Chi avrebbe potuto credere che io sarei stata costretta a scappare e nascondermi perché vuole uccidermi senza alcuna ragione?’

Così dicendo, proseguì verso il punto dal quale aveva udito provenire il belato, ma quale fu la sua sorpresa quando vide un grosso ariete in una graziosa piccola radura completamente circondata dagli alberi; il suo vello era bianco come la neve e le sue corna scintillavano come l’oro; aveva una ghirlanda di fiori intorno al collo, collane di grosse perle alle zampe e un collare di diamanti; era sdraiata su un manto di fiori arancioni, sotto un baldacchino di tessuto dorato che le riparava la testa dal sole. Lì vicino erano sparpagliate un centinaio di altre pecore, che non stavano brucando l’erba, ma alcune bevevano caffè, limonata o sorbetti, altre stavano mangiando gelati, fragole e panna o caramelle, mentre altre ancora stavano giocando. Molte di loro indossavano collari d’oro con pietre preziose, fiori e fiocchi.

Miranda si fermò all’istante stupefatta a questa inaspettata vista e stava cercando in ogni direzione il pastore di questo gregge sorprendente quando il magnifico ariete si diresse verso di lei.

“Avvicinati, graziosa principessa,” le disse, “non temere animali gentili e pacifici quali noi siamo.”

“Che meraviglia!” gridò la principessa, indietreggiando un po’, “Un ariete che parla.”

“La tua scimmia e il tuo cane parlavano, mia signora” disse l’animale, “sei stupita se noi facciamo altrettanto?” Miranda rispose: “Una fata aveva conferito loro il dono della parola così mi ero abituata.”

“Forse può esserci accaduta la medesima cosa,” disse l’ariete, sorridendo. “Principessa, che cosa può averti portato qui?”

“Una lunga serie di eventi sfortunati, messer ariete.” rispose la ragazza. “Sono la principessa più sfortunata del mondo e sto cercando protezione dalla collera di mio padre.”

“Vieni con me, mia signora,” disse l’ariete, “ti offro un nascondiglio che solo tu conoscerai e nel quale sarai padrona di ogni cosa che vedrai.”

Miranda rispose: “Davvero non posso seguirti perché sono troppo stanca per muovere un altro passo.”

L’ariete con le corna d’oro ordinò che fosse condotto il suo cocchio e un attimo dopo apparvero sei capre, imbrigliate a una zucca così grossa che due persone vi si sarebbero potute sedere dentro comodamente, ed era tutta imbottita di cuscini di velluto e di piuma. La principessa vi salì, assai divertita da questo nuovo tipo di carrozza, il re delle pecore prese posto accanto a lei e le capre corsero via a gran velocitò, fermandosi solo quando ebbero raggiunto una caverna, il cui ingresso era ostruito da una grossa pietra. Il re la toccò con una zampa e immediatamente essa cadde, poi invitò la principessa a entrare senza timore. Se non fosse stata così preoccupata da tutto ciò che le era accaduto, niente l’avrebbe indotta a entrare in quella paurosa caverna, ma era così spaventata di ciò che ci sarebbe potuto essere dietro di sé che in quel momento si sarebbe persino gettata in un pozzo. Così, senza esitazione, seguì l’ariete, che procedeva davanti a lei, giù, giù, giù finché pensò sarebbe giunti all’altro capo del mondo, infatti non era certa che l’ariete non la stesse conducendo nella terra delle fate. Alla fine vide davanti a sé una vasta pianura, ricoperta di ogni genere di fiori, il cui profumo le sembrò la cosa più bella che avesse mai sentito prima; un ampio fiume di succo d’arancia vi scorreva intorno e fontane di ogni tipo di vino scorrevano in tutte le direzioni creando i più graziosi cascate e ruscelli. La pianura era coperta dai più strani trani alberi che formavano interi viali in cui pernici ben arrostite pendevano da ogni ramo o, se preferivate, fagiani, quaglie, tacchini o conigli, avreste dovuto solo girare a destra o a sinistra e di sicuro li avreste trovati. In taluni posti l’aria era oscurata da una pioggia di pasticci di aragosta, tortini di carne, salsicce, torte e ogni genere di frutta candita o pezzetti d’oro e d’argento, diamanti e perle. Questa insolita pioggia e la piacevolezza del luogo senza dubbio avrebbero attratto un gran numero di persone, se il re delle pecore avesse avuto più predisposizione alla socializzazione, ma era evidente da ogni indizio che fosse severo come un giudice.

Siccome quello in Miranda era arrivata era il momento più gradevole dell’anno in quella terra deliziosa, l’unico palazzo che vide fu una lunga fila di alberi d’arancio, di gelsomino, di caprifoglio e di rose muschiate i cui rami intrecciati formavano le più graziose stanze dalle quali pendevano garze d’oro e d’argento e in cui vi erano grandi specchi e candelieri e i quadri più belli. Il meraviglioso ariete pregò la principessa di considerarsi la regina di tutto ciò che vedeva e le assicurò che, sebbene per molti anni fosse stato triste e in grandi difficoltà, lei aveva il potere di fargli dimenticare tutte le sue pene.

“Sei così gentile e generoso, nobile ariete,” disse la principessa, “che non potrò ringraziarti abbastanza, ma devo confessare che tutto ciò che vedo mi sembra così straordinario che non so che cosa pensare.”

Come ebbe parlato, un gruppo di graziose fate venne a offrirle cestini pieni di frutta, ma quando lei tese la mano verso di essi, scivolarono via e non poté sentir nulla quando tentò di toccarli.

“Che cosa sono?” gridò, Coin chi mi trovo?” e cominciò a piangere. In quel momento il re delle pecore tornò da lei e fu così turbato nel trovarla in lacrime che da strapparsi la lana del vello.

“Che succede, amabile principessa?” esclamò, “Qualcuno ha mancato di trattarvi con il dovuto rispetto?”

Miranda rispose: “Oh, no! è solo che non sono abituata a vivere con gli spiriti e con pecore che parlano, e tutto mi spaventa. È stato molto gentile da parte tua condurmi in questo luogo, ma ti sarei ancor più grata se mi conducessi di nuovo nel mondo di sopra.”

L’ariete meraviglioso disse: “Non temere, ti supplico di avere pazienza e di ascoltare la storia delle mie disgrazie. Un tempo ero un re e il mio regno era il più splendido al mondo. I sudditi mi amavano, i vicini mi invidiavano e mi temevano. Era rispettato da tutti e si diceva che nessun re lo avesse meritato di più.

“Ero assai appassionato di caccia e un giorno, mentre inseguivo un cervo, distanziai i miei attendenti; improvvisamente vidi l’animale saltare una pozza d’acqua e spronai avventatamente il mio cavallo per seguirlo, ma prima che avessimo fatto un po’ di passi, sentii un calore fuori del comune, invece del freddo dell’acqua; la pozza si prosciugò, davanti a me si aprì una grande abisso, dal quale si sprigionavano lingue di fuoco, e io caddi impotente sul fondo del precipizio.

“Mi davo già per spacciato, ma improvvisamente una voce disse. ‘Ingrato principe, nemmeno il fuoco è appena sufficiente a scaldare il tuo gelido cuore!’

‘“Chi si lamenta della mia freddezza in questo luogo lugubre?’ gridai.

‘“Un’infelice che ti ama senza speranza.’ rispose la voce, e nel medesimo istante le fiamme cominciarono a tremolare e a smettere di ardere e vidi una fata, che avevo conosciuto da così tanto tempo che non potevo rammentare quando, e la cui bruttezza mi aveva sempre fatto inorridire. Si appoggiava al braccio di una bellissima ragazza che portava catene d’oro ai polsi ed era evidentemente la sua schiava.

‘“Ragotte,’ dissi, perché questo era il nome della fata, “che significa tutto ciò? Mi trovo qui per tuo ordine?’ ‘“E di chi è la colpa,” rispose, ‘se finora non mi hai mai compresa? Una fata potente come me deve acconsentire a spiegare le proprie azioni a chi in confronto non è meglio di una formica, sebbene si ritenga un grande re?’

‘“Chiamami come ti pare,” dissi con impazienza, che cosa vuoi? La mia corona, le mie città o le mie ricchezze?’

‘“Ricchezze!’ esclamò la fata, sdegnosamente. “Se lo volessi, potrei rendere ognuno dei miei sguatteri più ricco e più potente di te. Non voglio le tue ricchezze,’ aggiunse sommessamente, ‘ma se mi concederai il tuo cuore, se mi sposerai, aggiungerò venti regni a ciascuno di quelli che già possiedi; avrai cento castelli pieni d’oro e cinquanta pieni d’argento e, in parole povere, qualsiasi cosa ti piaccia chiedermi.’

“Io dissi: ‘Madama Ragotte, quando uno si trova sul fondo di una fossa, in cui si aspetta di essere arso vivo, è impossibile pensare di chiedere di sposarlo a una persona affascinante come te! Ti chiedo di concedermi la libertà e allora potrò sperare di risponderti in modo appropriato.’

“Lei disse: ‘Se davvero mi ami, non dovrebbe importarti dove ti trovi – una grotta, una foresta, una tana di volpe, un deserto dovrebbero andarti bene ugualmente. Non pensare di potermi ingannare; hai voglia di tentare la fuga, ma ti assicuro sei destinato a restare qui e che la prima cosa ti darò da fare sarà custodire le mie pecore – sono un’ottima compagnia e parlano proprio come te.

“E come ebbe parlato, avanzò e mi condusse in questa pianura in cui ci troviamo, mi mostrò il gregge e ma io prestai poca attenzione a lei o a esso.

“Ad essere sincero, ero perso nell’ammirazione della sua splendida schiava al punto di dimenticare qualsiasi altra cosa, e la crudele Ragotte, accorgendosene, le lanciò un’occhiata così furiosa e terribile che cadde a terra morta.

“A questa vista spaventosa estrassi la spada e mi lanciai su Ragotte, certamente le avrei tagliato la testa se con le sue arti magiche non mi avesse incatenato sul posto nel quale mi trovato; vani furono tutti i miei sforzi per muovermi, e alla fine, quando mi lasciai cadere a terra disperato, mi disse con un sorriso sprezzante:

‘“Ho intenzione di farti provare il mio potere. Visto che al momento sembra tu sia un leone, voglio fare di te un ariete.’

“Così dicendo, mi toccò con la sua bacchetta e diventai come mi vedi. non ho perso l’uso della parola o la consapevolezza della miseria della mia attuale condizione.

‘“Sarai un ariete per cinque anni, “ disse, “il signore di questa terra desolata, mentre io, che non sopporto più a lungo di vedere il tuo volto così tanto amato, sarà meglio che impari a odiarti come meriti.’

“Come ebbe finito di parlare, sparì e se non fossi stato troppo infelice per curarmi di niente altro, sarei stato contento che se ne fosse andata.

“Le pecore parlanti mi accolsero come loro re e mi dissero che anche loro erano sfortunati principi che, in modi diversi, avevano offeso la vendicativa fata ed erano stati aggiunti al suo gregge per un certo numero di anni; quali più, quali meno. Di tanto in tanto, in verità, uno riacquistava l’aspetto originario e tornava al suo posto nel mondo superiore; ma gli altri che hai visto sono i rivali o i nemici di Ragotte, la quale li ha imprigionati per un centinaio d’anni circa benché alla fine torneranno indietro. La giovane schiava di cui ti ho parlato è una di loro; l’ho vista spesso e ciò mi procura un grande piacere. Non mi parla mai e se fossi più vicino a lei, so che troverei in lei solo un simulacro, la qual cosa sarebbe davvero irritante. In ogni modo ho notato che uno dei miei compagni di sventura è stato molto premuroso con questo spiritello e mi piace pensare che sia stato il suo innamorato, che la crudele Ragotte ha allontanato da lei da tempo; da allora me ne sono occupato e vi ho pensato, sebbene a nient’altro come al poter riconquistare la libertà. Sono stato spesso nella foresta, il luogo in cui ti ho vista, deliziosa principessa, a volte mentre guidavi la tua carrozza, cosa che facevi con tutta la grazia e l’abilità del mondo, a volte mentre cavalcavi in sella a un cavallo così vivace che nessun altro all’infuori di te sembrava potesse condurre, e altre volte mentre correvi a gara con le principesse della tua corte, correndo così velocemente che eri sempre tu a vincere il premio. Oh, principessa, ti ho amata così a lungo e ora come posso osare parlarti del mio amore! Che speranza ci può essere per un infelice ariete come me?”

Miranda era così sorpresa e confusa da tutto ciò che aveva sentito che a malapena sapeva che cosa rispondere al re delle pecore, ma riuscì a pronunciare qualche parola gentile, che certamente non gli avrebbe impedito di sperare, e disse che non avrebbe avuto paura delle ombre ora che sapeva un giorno sarebbero tornate di nuovo alla vita. Poi continuò: “Ahimè, se la mia povera Patypata, la mia cara Grabugeon e il grazioso e piccolo Tintin, che sono morti per la mia salvezza, fossero nella medesima condizione, qui non avrei altro da desiderare!”

Sebbene fosse prigioniero, il re delle pecore aveva ancora alcuni poteri e privilegi.

“Vai, “disse al signore dei cavalli, “vai e cerca le ombre della piccola ragazza nera, della scimmia e del cane: intratterranno la nostra principessa.”

Un momento dopo Miranda li vide venire verso di lei e la loro presenza le diede il piacere più grande, sebbene non si avvicinassero abbastanza da toccarli.

Il re delle pecore era così gentile e divertente, e amava Miranda così teneramente che alla fine anche lei cominciò ad amarlo. Un ariete così avvenente. Che era tanto garbato e stimato, difficilmente non poteva piacere, specialmente se uno sapeva che si trattava di un re e che la sua strana prigionia sarebbe presto giunta alla fine. Così i giorni della principessa trascorrevano assai allegramente mentre aspettava che venisse il tempo della felicità. Il re delle pecore, con l’aiuto del gregge, organizzava balli, concerti e battute di caccia, e persino le ombre godevano di tutto il divertimento e venivano, facendo credere di essere i loro veri se stessi.

Una sera, quando giunsero i corrieri (perché il re delle pecore ne inviava molti a procurarsi con cura le notizie) - che ne portavano sempre del genere migliore – fu annunciato che la sorella della principessa Miranda stava per sposare un grande principe e che nulla sarebbe stato più splendido dei preparativi per le nozze.

La giovane principessa esclamò: “Come sono sfortunata a perdere la possibilità di vedere così tante belle cose! Sono qui imprigionata sotto terra, senza nessun’altra compagnia che pecore e ombre, mentre mia sorella sta per essere adornata come una regina e circondata da chiunque la ami e la ammiri, e tutti tranne me possono andare a condividere la sua gioia!”

“Perché ti lamenti?” disse il re delle pecore. “Ti ho detto che non puoi andare alle nozze? Preparati più in fretta che puoi, solo promettimi che tornerai perché ti amo troppo per riuscire a vivere senza di te.”

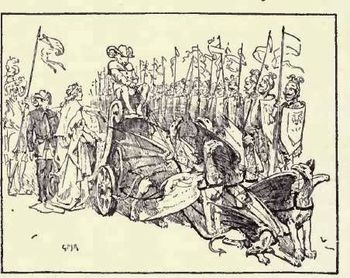

Miranda gli fu assai grata e promise lealmente che nulla al mondo l’avrebbe trattenuta dal tornare indietro. Il re procurò che una scorta adeguata al suo rango fosse approntata per lei, la principessa si vestì splendidamente, senza dimenticare nulla che potesse renderla ancora più bella. La sua carrozza era di madreperla, trainata da sei grifoni bruni procurati dall’altra parte del mondo, ed era scortata da un certo numero di guardie dalle splendide uniformi, le quali erano tutte alte otto piedi e provenivano da vicino e da lontano per condurre il corteo della principessa.

Miranda raggiunse il palazzo di suo padre appena prima che cominciasse la cerimonia nuziale e ognuno, appena lei entrò, fu colto da sorpresa alla sua bellezza e allo splendore dei suoi gioielli. Sentì esclamazioni di ammirazione da ogni parte; il re suo padre la guardò così attentamente che ebbe paura che potesse riconoscerla; però lui era così certo della sua morte che l’idea non lo sfiorò neppure.

In ogni modo la paura di non potersene andare la fece partire prima che il matrimonio fosse concluso. Uscì in fretta, lasciandosi dietro un piccolo cestino di corallo tempestato di smeraldi. Su di esso era scritto con lettere di diamanti: ‘gioielli per la sposa’ e quando l’aprirono, come fecero appena l’ebbero trovato, sembrava non finissero mai le belle cose contenute. Il re, che aveva sperato di raggiungere la principessa sconosciuta e di scoprire chi fosse, fu terribilmente deluso quando lei scomparve così improvvisamente e diede ordini che le porte fossero chiuse, nel caso lei giungesse di nuovo, così che non potesse andarsene tanto facilmente. Per quanto breve fosse stata l’assenza di Miranda, al re delle pecore sembrò lunga cent’anni. La stava spettando presso la fontana nella parte più folta della foresta e il terreno era coperto dagli splendidi doni che aveva preparato per lei, per mostrare gioia e gratitudine per il suo ritorno.

Appena lei fu visibile, si affrettò a incontrarla, saltando e balzando come un vero ariete. La accarezzò teneramente, gettandosi ai suoi piedi e baciandole le mani, e le raccontò quanto fosse stato inquieto in sua assenza e quanto fosse impaziente per il suo ritorno con un’eloquenza che la affascinò.

Dopo un po’ di tempo giunse la notizia che anche la seconda figlia del re stava per sposarsi. Quando Miranda lo sentì, pregò il re delle pecore di permetterle di andare a vedere il matrimonio come la volta precedente. La richiesta lo rese assai triste, come se di certo altre sfortune lo colpissero, ma il suo amore per la principessa era tanto più forte di qualsiasi altra cosa che non se la sentì di rifiutare.

“Tu desideri lasciarmi, principessa,” disse, “è il mio infelice destino – non sei da biasimare. Acconsento che tu vada, ma, credimi, non posso darti più grande prova del mio amore di ciò che sto facendo.”

La principessa gli assicurò che sarebbe rimasta per pochissimo tempo, come aveva fatto la volta precedente, e lo pregò di non stare in ansia perché lei si sarebbe addolorata molto se qualcosa l’avesse trattenuta.

Così, con la medesima scorta, lei se ne andò e raggiunse il palazzo mentre cominciava la cerimonia delle nozze. Tutti furono lieti di vederla; era così graziosa che pensavano dovesse essere una qualche principessa delle fate, e i principi che erano là non le tolsero gli occhi di dosso.

Il re era più contento di chiunque altro che lei fosse tornata di nuovo e diede ordine che le porte tutte chiuse e sprangate proprio in quel momento. Quando le nozze erano quasi celebrate la principessa si alzò rapidamente, sperando di sgattaiolare via inosservata tra la folla ma, con suo grande sgomento, trovò le porte serrate.

Si sentì meglio quando il re venne da lei e con il più grande rispetto la pregò di non correre via così presto, ma di onorarlo fermandosi allo splendido banchetto che era stato allestito per il principe e la principessa. La condusse in una magnifica sala in cui era riunita tutta la corte e lui stesso, sollevando la ciotola d’oro piena d’acqua, gliela offrì affinché potesse sciacquarvisi le dita.

A questo punto la principessa non poté trattenersi più a lungo; gettandosi ai piedi del re, esclamò:

“Dopotutto il mio sogno è diventato realtà, mi avete offerto l’acqua per lavarmi le mani il giorno delle nozze di mia sorella e non vi ha preoccupato farlo.”

Il re la riconobbe subito – in verità aveva pensato molte volte a che cosa ne fisse stato della sua povera e piccolo Miranda.

“Mia cara figlia,” esclamò, baciandola, “potrai mai perdonare la mia crudeltà? Ho ordinato che tu fossi messa a morte perché pensavo che il tuo sogno presagisse la perdita della corona da parte mia. E così è stato” aggiunse, “perché ora entrambe le tue sorelle sono sposate e hanno i loro regni e il mio sarà per te.” Così dicendo, depose la corona sulla testa della principessa e gridò:

“Lunga vita alla regina Miranda!”

Tutta la corte gridò dopo di lui: “Lunga vita alla regina Miranda!” e le due sorelle della giovane regina vennero di corsa e le gettarono le braccia al collo, baciandola migliaia di volte, poi ci furono molte risate e molte lacrime, e chiacchiere e baci, allo stesso tempo, e Miranda ringraziò il padre e cominciò a domandare di ognuno, in particolare del capitano delle guardie al quale doveva tanto; ma con suo grande dispiacere apprese che era morto. Subito sedettero al banchetto e il re chiese a Miranda di raccontargli tutto quello che le era accaduto dalla terribile mattina in cui aveva mandato il capitano delle guardie a prenderla. Lo fece con così tanto spirito che tutti gli ospiti l’ascoltarono trattenendo il fiato per l’interesse. Ma mentre si stava divertendo con il re e con le sorelle, il re delle pecore stava aspettando con impazienza il momento del suo ritorno e quando esso venne e se ne andò, e la principessa non apparve, la sua ansia diventò così grande che non poté sopportarla più a lungo.

“Lei non tornerà più,” gridò, “il mio miserabile aspetto di ariete la disgusta e senza Miranda che cosa mi rimane, sventurata creatura che sono! Oh! Crudele Ragotte, la mia punizione è completa.”

A lungo compianse il proprio triste destino e poi, vedendo che si stava facendo buio e che ancora non vi era traccia della principessa, si diresse il più rapidamente possibile verso la città. Quando raggiunse il palazzo, chiese di Miranda, ma a quel punto tutti aveva udito la storia delle sue avventure e non volevano riportarla dal re delle pecore, così rifiutarono decisamente di lasciargliela vedere. Invano li implorò e li pregò di condurlo dentro; sebbene le sue suppliche avrebbero intenerito cuori di pietra, non commossero le guardie del palazzo e alla fine, con il cuore a pezzi, cadde morto ai loro piedi.

Nel medesimo tempo il re, il quale non aveva idea del triste fatto che stava accadendo fuori dal cancello del palazzo, propose a Miranda di essere condotta in carrozza per tutta la città, che era illuminata da migliaia e migliaia di fiaccole, collocate alle finestre, ai balconi e in tutte le grandi piazze. Ma che cosa videro i suoi occhi proprio all’ingresso del palazzo! Lì sul pavimento giaceva il suo caro, gentile re delle pecore, silenzioso e immobile!

Si gettò giù dalla carrozza e corse da lui, piangendo amaramente, perché comprese che la promessa infranta gli era costata la vita e per molto, molto tempo fu così infelice e tutti pensavano ne sarebbe morta.

Così vedete che persino una principessa non è sempre felice, specialmente se dimentica di mantenere la parola data; e le più grandi disgrazie spesso accadono alle persone proprio quando pensano di aver ottenuto ciò che i loro cuori desiderano!

Madame d’Aulnoy.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)