There was, once upon a time, a man and his wife fagot-makers by trade, who had several children, all boys. The eldest was but ten years old, and the youngest only seven.

They were very poor, and their seven children incommoded them greatly, because not one of them was able to earn his bread. That which gave them yet more uneasiness was that the youngest was of a very puny constitution, and scarce ever spoke a word, which made them take that for stupidity which was a sign of good sense. He was very little, and when born no bigger than one’s thumb, which made him be called Little Thumb.

The poor child bore the blame of whatsoever was done amiss in the house, and, guilty or not, was always in the wrong; he was, notwithstanding, more cunning and had a far greater share of wisdom than all his brothers put together; and, if he spake little, he heard and thought the more.

There happened now to come a very bad year, and the famine was so great that these poor people resolved to rid themselves of their children. One evening, when they were all in bed and the fagot-maker was sitting with his wife at the fire, he said to her, with his heart ready to burst with grief:

“Thou seest plainly that we are not able to keep our children, and I cannot see them starve to death before my face; I am resolved to lose them in the wood to-morrow, which may very easily be done; for, while they are busy in tying up fagots, we may run away, and leave them, without their taking any notice.”

“Ah!” cried his wife; “and canst thou thyself have the heart to take thy children out along with thee on purpose to lose them?”

In vain did her husband represent to her their extreme poverty: she would not consent to it; she was indeed poor, but she was their mother. However, having considered what a grief it would be to her to see them perish with hunger, she at last consented, and went to bed all in tears.

Little Thumb heard every word that had been spoken; for observing, as he lay in his bed, that they were talking very busily, he got up softly, and hid himself under his father’s stool, that he might hear what they said without being seen. He went to bed again, but did not sleep a wink all the rest of the night, thinking on what he had to do. He got up early in the morning, and went to the river-side, where he filled his pockets full of small white pebbles, and then returned home.

They all went abroad, but Little Thumb never told his brothers one syllable of what he knew. They went into a very thick forest, where they could not see one another at ten paces distance. The fagot-maker began to cut wood, and the children to gather up the sticks to make fagots. Their father and mother, seeing them busy at their work, got away from them insensibly, and ran away from them all at once, along a by-way through the winding bushes.

When the children saw they were left alone, they began to cry as loud as they could. Little Thumb let them cry on, knowing very well how to get home again, for, as he came, he took care to drop all along the way the little white pebbles he had in his pockets. Then he said to them:

“Be not afraid, brothers; father and mother have left us here, but I will lead you home again, only follow me.”

They did so, and he brought them home by the very same way they came into the forest. They dared not go in, but sat themselves down at the door, listening to what their father and mother were saying.

The very moment the fagot-maker and his wife reached home, the lord of the manor sent them ten crowns, which he had owed them a long while, and which they never expected. This gave them new life, for the poor people were almost famished. The fagot-maker sent his wife immediately to the butcher’s. As it was a long while since they had eaten a bit, she bought thrice as much meat as would sup two people. When they had eaten, the woman said:

“Alas! where are now our poor children? they would make a good feast of what we have left here; but it was you, William, who had a mind to lose them: I told you we should repent of it. What are they now doing in the forest? Alas! dear God, the wolves have perhaps already eaten them up; thou art very inhuman thus to have lost thy children.”

The fagot-maker grew at last quite out of patience, for she repeated it above twenty times, that they should repent of it, and that she was in the right of it for so saying. He threatened to beat her if she did not hold her tongue. It was not that the fagot-maker was not, perhaps, more vexed than his wife, but that she teased him, and that he was of the humor of a great many others, who love wives to speak well, but think those very importunate who are continually doing so. She was half-drowned in tears, crying out:

“Alas! where are now my children, my poor children?”

She spoke this so very loud that the children, who were at the gate, began to cry out all together:

“Here we are! Here we are!”

She ran immediately to open the door, and said, hugging them:

“I am glad to see you, my dear children; you are very hungry and weary; and my poor Peter, thou art horribly bemired; come in and let me clean thee.”

Now, you must know that Peter was her eldest son, whom she loved above all the rest, because he was somewhat carroty, as she herself was. They sat down to supper, and ate with such a good appetite as pleased both father and mother, whom they acquainted how frightened they were in the forest, speaking almost always all together. The good folks were extremely glad to see their children once more at home, and this joy continued while the ten crowns lasted; but, when the money was all gone, they fell again into their former uneasiness, and resolved to lose them again; and, that they might be the surer of doing it, to carry them to a much greater distance than before.

They could not talk of this so secretly but they were overheard by Little Thumb, who made account to get out of this difficulty as well as the former; but, though he got up very early in the morning to go and pick up some little pebbles, he was disappointed, for he found the house-door double-locked, and was at a stand what to do. When their father had given each of them a piece of bread for their breakfast, Little Thumb fancied he might make use of this instead of the pebbles by throwing it in little bits all along the way they should pass; and so he put the bread in his pocket.

Their father and mother brought them into the thickest and most obscure part of the forest, when, stealing away into a by-path, they there left them. Little Thumb was not very uneasy at it, for he thought he could easily find the way again by means of his bread, which he had scattered all along as he came; but he was very much surprised when he could not find so much as one crumb; the birds had come and had eaten it up, every bit. They were now in great affliction, for the farther they went the more they were out of their way, and were more and more bewildered in the forest.

Night now came on, and there arose a terribly high wind, which made them dreadfully afraid. They fancied they heard on every side of them the howling of wolves coming to eat them up. They scarce dared to speak or turn their heads. After this, it rained very hard, which wetted them to the skin; their feet slipped at every step they took, and they fell into the mire, whence they got up in a very dirty pickle; their hands were quite benumbed.

Little Thumb climbed up to the top of a tree, to see if he could discover anything; and having turned his head about on every side, he saw at last a glimmering light, like that of a candle, but a long way from the forest. He came down, and, when upon the ground, he could see it no more, which grieved him sadly. However, having walked for some time with his brothers toward that side on which he had seen the light, he perceived it again as he came out of the wood.

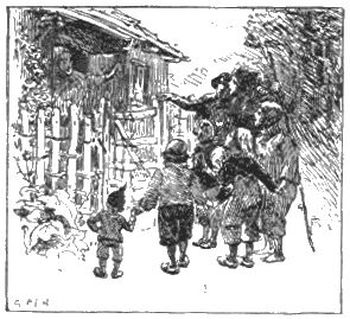

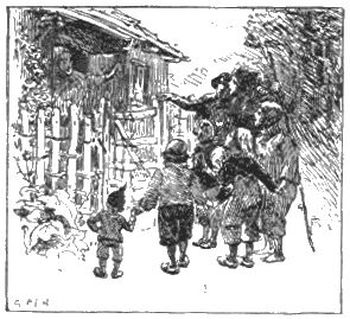

They came at last to the house where this candle was, not without an abundance of fear: for very often they lost sight of it, which happened every time they came into a bottom. They knocked at the door, and a good woman came and opened it; she asked them what they would have.

Little Thumb told her they were poor children who had been lost in the forest, and desired to lodge there for God’s sake.

The woman, seeing them so very pretty, began to weep, and said to them:

“Alas! poor babies; whither are ye come? Do ye know that this house belongs to a cruel ogre who eats up little children?”

“Ah! dear madam,” answered Little Thumb (who trembled every joint of him, as well as his brothers), “what shall we do? To be sure the wolves of the forest will devour us to-night if you refuse us to lie here; and so we would rather the gentleman should eat us; and perhaps he may take pity upon us, especially if you please to beg it of him.”

The Ogre’s wife, who believed she could conceal them from her husband till morning, let them come in, and brought them to warm themselves at a very good fire; for there was a whole sheep upon the spit, roasting for the Ogre’s supper.

As they began to be a little warm they heard three or four great raps at the door; this was the Ogre, who had come home. Upon this she hid them under the bed and went to open the door. The Ogre presently asked if supper was ready and the wine drawn, and then sat himself down to table. The sheep was as yet all raw and bloody; but he liked it the better for that. He sniffed about to the right and left, saying:

“I smell fresh meat.”

“What you smell so,” said his wife, “must be the calf which I have just now killed and flayed.”

“I smell fresh meat, I tell thee once more,” replied the Ogre, looking crossly at his wife; “and there is something here which I do not understand.”

As he spoke these words he got up from the table and went directly to the bed.

“Ah, ah!” said he; “I see then how thou wouldst cheat me, thou cursed woman; I know not why I do not eat thee up too, but it is well for thee that thou art a tough old carrion. Here is good game, which comes very quickly to entertain three ogres of my acquaintance who are to pay me a visit in a day or two.”

With that he dragged them out from under the bed one by one. The poor children fell upon their knees, and begged his pardon; but they had to do with one of the most cruel ogres in the world, who, far from having any pity on them, had already devoured them with his eyes, and told his wife they would be delicate eating when tossed up with good savory sauce. He then took a great knife, and, coming up to these poor children, whetted it upon a great whet-stone which he held in his left hand. He had already taken hold of one of them when his wife said to him:

“Why need you do it now? Is it not time enough to-morrow?”

“Hold your prating,” said the Ogre; “they will eat the tenderer.

“But you have so much meat already,” replied his wife, “you have no occasion; here are a calf, two sheep, and half a hog.”

“That is true,” said the Ogre; “give them their belly full that they may not fall away, and put them to bed.”

The good woman was overjoyed at this, and gave them a good supper; but they were so much afraid they could not eat a bit. As for the Ogre, he sat down again to drink, being highly pleased that he had got wherewithal to treat his friends. He drank a dozen glasses more than ordinary, which got up into his head and obliged him to go to bed.

The Ogre had seven daughters, all little children, and these young ogresses had all of them very fine complexions, because they used to eat fresh meat like their father; but they had little gray eyes, quite round, hooked noses, and very long sharp teeth, standing at a good distance from each other. They were not as yet over and above mischievous, but they promised very fair for it, for they had already bitten little children, that they might suck their blood.

They had been put to bed early, with every one a crown of gold upon her head. There was in the same chamber a bed of the like bigness, and it was into this bed the Ogre’s wife put the seven little boys, after which she went to bed to her husband.

Little Thumb, who had observed that the Ogre’s daughters had crowns of gold upon their heads, and was afraid lest the Ogre should repent his not killing them, got up about midnight, and, taking his brothers’ bonnets and his own, went very softly and put them upon the heads of the seven little ogresses, after having taken off their crowns of gold, which he put upon his own head and his brothers’, that the Ogre might take them for his daughters, and his daughters for the little boys whom he wanted to kill.

All this succeeded according to his desire; for, the Ogre waking about midnight, and sorry that he deferred to do that till morning which he might have done over-night, threw himself hastily out of bed, and, taking his great knife,

“Let us see,” said he, “how our little rogues do, and not make two jobs of the matter.”

He then went up, groping all the way, into his daughters’ chamber, and, coming to the bed where the little boys lay, and who were every soul of them fast asleep, except Little Thumb, who was terribly afraid when he found the Ogre fumbling about his head, as he had done about his brothers’, the Ogre, feeling the golden crowns, said:

“I should have made a fine piece of work of it, truly; I find I drank too much last night.”

Then he went to the bed where the girls lay; and, having found the boys’ little bonnets, “Ah!” said he, “my merry lads, are you there? Let us work as we ought.”

And saying these words, without more ado, he cut the throats of all his seven daughters.

Well pleased with what he had done, he went to bed again to his wife. So soon as Little Thumb heard the Ogre snore, he waked his brothers, and bade them all put on their clothes presently and follow him. They stole down softly into the garden, and got over the wall. They kept running about all night, and trembled all the while, without knowing which way they went.

The Ogre, when he awoke, said to his wife: “Go upstairs and dress those young rascals who came here last night.”

The wife was very much surprised at this goodness of her husband, not dreaming after what manner she should dress them; but, thinking that he had ordered her to go and put on their clothes, she went up, and was strangely astonished when she perceived her seven daughters killed, and weltering in their blood.

She fainted away, for this is the first expedient almost all women find in such cases. The Ogre, fearing his wife would be too long in doing what he had ordered, went up himself to help her. He was no less amazed than his wife at this frightful spectacle.

“Ah! what have I done?” cried he. “The wretches shall pay for it, and that instantly.”

He threw a pitcher of water upon his wife’s face, and, having brought her to herself, said: “Give me quickly my boots of seven leagues, that I may go and catch them.”

He went out, and, having run over a vast deal of ground, both on this side and that, he came at last into the very road where the poor children were, and not above a hundred paces from their father’s house. They espied the Ogre, who went at one step from mountain to mountain, and over rivers as easily as the narrowest kennels. Little Thumb, seeing a hollow rock near the place where they were, made his brothers hide themselves in it, and crowded into it himself, minding always what would become of the Ogre.

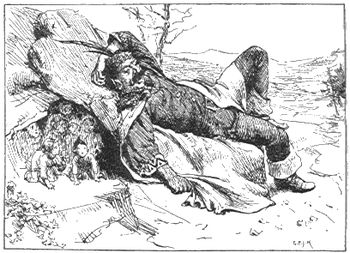

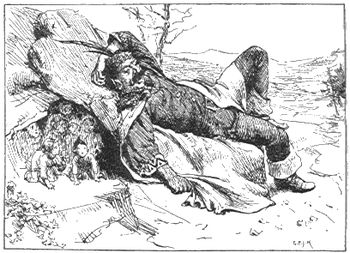

The Ogre, who found himself much tired with his long and fruitless journey (for these boots of seven leagues greatly fatigued the wearer), had a great mind to rest himself, and, by chance, went to sit down upon the rock where the little boys had hid themselves.

As it was impossible he could be more weary than he was, he fell asleep, and, after reposing himself some time, began to snore so frightfully that the poor children were no less afraid of him than when he held up his great knife and was going to cut their throats. Little Thumb was not so much frightened as his brothers, and told them that they should run away immediately toward home while the Ogre was asleep so soundly, and that they should not be in any pain about him. They took his advice, and got home presently. Little Thumb came up to the Ogre, pulled off his boots gently and put them on his own legs. The boots were very long and large, but, as they were fairies, they had the gift of becoming big and little, according to the legs of those who wore them; so that they fitted his feet and legs as well as if they had been made on purpose for him. He went immediately to the Ogre’s house, where he saw his wife crying bitterly for the loss of the Ogre’s murdered daughters.

“Your husband,” said Little Thumb, “is in very great danger, being taken by a gang of thieves, who have sworn to kill him if he does not give them all his gold and silver. The very moment they held their daggers at his throat he perceived me, and desired me to come and tell you the condition he is in, and that you should give me whatsoever he has of value, without retaining any one thing; for otherwise they will kill him without mercy; and, as his case is very pressing, he desired me to make use (you see I have them on) of his boots, that I might make the more haste and to show you that I do not impose upon you.”

The good woman, being sadly frightened, gave him all she had: for this Ogre was a very good husband, though he used to eat up little children. Little Thumb, having thus got all the Ogre’s money, came home to his father’s house, where he was received with abundance of joy.

There are many people who do not agree in this circumstance, and pretend that Little Thumb never robbed the Ogre at all, and that he only thought he might very justly, and with a safe conscience, take off his boots of seven leagues, because he made no other use of them but to run after little children. These folks affirm that they are very well assured of this, and the more as having drunk and eaten often at the fagot-maker’s house. They aver that when Little Thumb had taken off the Ogre’s boots he went to Court, where he was informed that they were very much in pain about a certain army, which was two hundred leagues off, and the success of a battle. He went, say they, to the King, and told him that, if he desired it, he would bring him news from the army before night.

The King promised him a great sum of money upon that condition. Little Thumb was as good as his word, and returned that very same night with the news; and, this first expedition causing him to be known, he got whatever he pleased, for the King paid him very well for carrying his orders to the army. After having for some time carried on the business of a messenger, and gained thereby great wealth, he went home to his father, where it was impossible to express the joy they were all in at his return. He made the whole family very easy, bought places for his father and brothers, and, by that means, settled them very handsomely in the world, and, in the meantime, made his court to perfection.

Charles Perrault

Pollicino

C’erano una volta un uomo e una donna, entrambi taglialegna, i quali avevano sette figli, tutti maschi. Il maggiore aveva dieci anni e il minore sei.

Erano molto poveri e quei sette figli li angustiavano enormemente perché nessuno di loro era in grado di procurarsi il pane. Ma ciò che dava loro maggior fastidio era il fatto che il più piccolo fosse di costituzione assai gracile e spiccicasse a stento parola, il che faceva loro scambiare per stupidità ciò che era segno di buon senso. Era molto piccolo e quando era nato non era più grande di un pollice per cui era stato chiamato Pollicino.

Il povero bambino subiva il biasimo di chiunque entrasse in casa e, colpevole o no, era sempre ritenuto in errore; ciononostante era molto astuto, era molto più saggio di tutti i suoi fratelli messi insieme e, se parlava poco, ascoltava e pensava molto.

Capitò che fosse venuta una gran brutta annata e la fame fosse così grande che questi poveri diavoli decisero di sbarazzarsi dei loro figli. Una sera, quando erano tutti a letto e il taglialegna era seduto davanti al fuoco con la moglie, le disse con il cuore sul punto di scoppiare per il dolore:

“Come vedi chiaramente, non siamo in grado di allevare i nostri figli e io non posso vederli morire di fame sotto i miei occhi; ho deciso di abbandonarli nel bosco domani, il che sarà molto facile perché, mentre saranno occupati a legare le fascine, noi potremo correre via e lasciarli senza che ne accorgano.”

La moglie esclamò: “Come puoi avere il cuore di portare con te i bambini allo scopo di abbandonarli?”

Invano il marito le illustrò la loro estrema povertà, lei non voleva acconsentire; era davvero povera, ma era la loro mamma. In ogni modo, avendo considerato che dolore sarebbe stato per lei vederli morire di fame, infine acconsentì e andò a letto in lacrime.

Pollicino aveva sentito ogni parola che era stata pronunciata; avendo notato, mentre era a letto, che stavano parlando di cose serie, si era alzato silenziosamente e si era nascosto sotto lo sgabello del padre, il che gli aveva permesso di ascoltare senza essere visto. Era andato a letto di nuovo, ma non aveva chiuso occhio per tutto il resto della notte, pensando a ciò che doveva fare. La mattina si alzò presto, andò sulla riva del fiume dove si riempì le tasche di sassolini bianchi e poi tornò a casa.

Partirono tutti, ma Pollicino non disse ai fratelli una sillaba di ciò che sapeva. Entrarono in una foresta così folta in cui non si vedevano l’un l’altro a dieci passi di distanza. Il taglialegna cominciò a tagliare la legna e i bambini raccoglievano i ramoscelli per farne fascine. Il padre e la madre, vedendoli occupati, si allontanarono senza che se ne accorgessero e corsero via subito da loro per un passaggio attraverso la tortuosa boscaglia.

Quando i bambini si accorsero di essere rimasti soli, cominciarono a piangere più forte che poterono. Pollicino li lasciò piangere, sapendo come riportarli a casa, perché mentre venivano aveva lasciato cadere lungo la strada i sassolini bianchi che teneva in tasca. Allora disse loro:

“Non abbiate paura, fratelli; il papà e la mamma ci hanno lasciati qui ma io vi porterò di nuovo a casa, seguitemi.”

Lo fecero e lui li condusse a casa per la medesima via che avevano percorso nella foresta. Non osarono entrare, ma sedettero alla porta, ascoltando ciò che il padre e la madre stavano dicendo.

Proprio nel momento in cui il taglialegna e sua moglie erano tornati a casa, il signore del castello aveva mandato dieci corone che da tempo doveva loro e che non si aspettavano più. Ciò li restituì alla vita perché quei poveretti erano ridotti alla fame. Il taglialegna mandò immediatamente la moglie dal macellaio. Siccome era molto tempo che non mangiavano, lei comprò tre volte più carne di quanta ne servisse per il pasto di due persone. Quando ebbero mangiato, la donna disse:

“Ahimè, dove saranno adesso i nostri poveri bambini? Avrebbero potuto fare festa con tutto ciò che è rimasto qui, ma sei stato tu, William, che ti sei fatto venire in mente di abbandonarli: te l’avevo detto che ce ne saremmo pentiti. Che cosa staranno facendo nella foresta? Buon Dio, forse i lupi li avranno già mangiati; sei stato davvero senza cuore ad abbandonare i tuoi bambini.”

Alla fine il taglialegna perse la pazienza perché lei aveva ripetuto almeno venti volte che se ne sarebbero pentiti e che aveva ragione nel dirglielo. Minacciò di picchiarla se non avesse tenuto a freno la lingua. Non che il taglialegna non fosse addirittura più preoccupato della moglie, ma lei lo stuzzicava e lui non era simile a tanti altri che amano le mogli che parlano bene, ma si sentono assai infastiditi che lo facciano continuamente. Lei quasi si scioglieva in lacrime, gridando:

“Ahimè! Dove saranno adesso i miei bambini, i miei poveri bambini?”

Parlava a voce così alta che i bambini, i quali erano al cancello, cominciarono a strillare tutti insieme:

“Siamo qui! Siamo qui!”

Lei corse immediatamente ad aprire la porta e disse, abbracciandoli:

“Sono felice di vedervi, miei cari bambini; dovete essere molto affamati e stanchi, e tu, mio povero Peter, sei terribilmente infangato, entra e lascia che ti pulisca.”

Dovete sapere che Peter era il figlio maggiore, quello che amava più degli altri perché aveva i capelli rossicci come lei. Sedettero a cena e mangiarono con tale appetito che rese felici il padre e la madre, ai quali raccontarono che paura avessero avuto nella foresta, parlando quasi sempre tutti insieme. Quelle brave persone erano molto felici di vedere i figli ancora una volta a casa e la gioia durò quanto le dieci corone, ma quando il denaro fu finito, ricaddero nell’abituale precarietà e decisero di abbandonarli di nuovo e, per essere sicuri di riuscirci, di portarli molto più lontano della volta precedente.

Per quanto ne parlassero in segretezza, furono sentiti da Pollicino il quale pensò di trarsi d’impaccio come aveva fatto la prima volta ma, sebbene si fosse svegliato molto presto il mattino per andare a prendere alcuni ciottoli, rimase deluso perché trovò la porta chiusa a doppia mandata e rimase impalato senza sapere che fare. Quando il padre ebbe dato a ciascuno di loro un pezzo di pane per colazione, Pollicino pensò che avrebbe potuto usarlo invece dei ciottoli, gettandolo in briciole lungo la strada sulla quale sarebbero passati, così mise il pane in tasca.

Il padre e la madre li condussero nella parte più folta e oscura della foresta e li lasciarono lì, allontanandosi furtivamente per un sentiero secondario. Pollicino non se ne preoccupò troppo perché pensava sarebbe stato facile trovare di nuovo la strada grazie alle briciole che aveva seminato mentre giungevano lì; fu molto sorpreso quando non ne trovò neppure una; gli uccelli erano venuti e avevano mangiato ogni briciola. Adesso si trovavano in grande angustia perché più procedevano, più smarrivano la via nella foresta e si sentivano sempre più sconcertati.

Scese la notte e si alzo un vento fortissimo che li spaventò a morte. Credevano di sentire da ogni parte l’ululato dei lupi che venivano a mangiarli. A malapena osavano parlare o volgere le teste. Dopodiché piovve molto forte e si inzupparono; i piedi scivolavano ad ogni passo e cadevano nella mota, dalla quale si sollevavano assai infangati con le mani completamente intorpidite.

Pollicino si arrampicò su un albero per vedere se scorgeva qualcosa e, avendo girato la testa da ogni parte, infine vide un barlume, come quello di una candela, ma a lunga distanza oltre la foresta. Scese e quando fu a terra non lo vide più, cosa che lo rattristò molto. In ogni modo, avendo camminato con i fratelli per un po’ di tempo nella direzione in cui aveva visto la luce, riuscì a vederla di nuovo come furono usciti dal bosco.

Giunsero infine alla casa in cui brillava la candela, non senza tanta paura perché spesso l’avevano persa di vista, cosa che accadeva ogni volta in cui scendevano in un avvallamento. Bussarono alla porta e una brava donna venne ad aprire, chiedendo loro che cosa volessero.

Pollicino le disse che erano poveri bambini abbandonati nella foresta e che desideravano un ricovero per amor di Dio.

Vedendo quanto fossero graziosi, la donna cominciò a piangere e disse loro:

“Ahimè, poveri bambini, da dove venite? Non sapete che questa è la casa di un orco crudele che mangia i bambini?”

“Ahimè, signora,” rispose Pollicino, che tremava tutto come i suoi fratelli, “che cosa possiamo fare? Potete star certa che i lupi stanotte ci divoreranno se rifiuterete di accoglierci qui; preferiremmo piuttosto che fosse quel gentiluomo a mangiarci e forse potrebbe aver pietà di noi, specialmente se voi lo pregaste in tal senso.”

La moglie dell’orco, che riteneva di poterli nascondere al marito fino al mattino, li lasciò entrare e li condusse a scaldarsi presso un gran bel fuoco perché lì vi era sullo spiedo una pecora intera che arrostiva per la cena dell’orco.

Avevano appena cominciato a riscaldarsi che udirono tre o quattro robusti colpi alla porta: era l’orco che tornava a casa. Perciò lei li fece nascondere sotto il letto e andò ad aprire la porta. L’orco chiese subito se fosse pronta la cena e il vino versato, poi sedette a tavola. La pecora era ancora al sangue, ma a lui piaceva di più per questo. Annusò a destra e a sinistra, dicendo:

“Sento odore di carne fresca.”

La moglie disse: “L’odore che senti deve essere quello del vitello che ho appena ammazzato e scuoiato.”

“Sento odore di carne fresca, te lo dico ancora una volta” rispose l’orco, guardando rabbioso la moglie “e qui c’è qualcosa che non capisco.”

Mentre pronunciava queste parole, da tavola andò direttamente verso il letto.

“Vedo che volevi imbrogliarmi, maledetta donna! Non so perché non mangi anche te, buon per te che sei una carogna vecchia e coriacea. Capita a proposito per ricevere tre orchi di mia conoscenza che verranno a farmi vista tra un giorno o due.”

Con queste parole li trascinò fuori uno per uno da sotto il letto. I poveri bambini caddero in ginocchio e implorarono perdono; avevano però che fare con uno degli orchi più crudeli del mondo il quale, ben lungi dal provare pietà di loro, li stava già divorando con gli occhi e disse alla moglie che sarebbero stati un cibo prelibato una volta conditi con una buona salsa saporita. Allora afferrò un grosso coltello e, avvicinandosi a quei poveri bambini, lo affilò su una grossa cote che teneva nella mano sinistra. Ne aveva già quasi agguantato uno quando la moglie gli disse:

“Che bisogno c’è di farlo adesso? Non avrai abbastanza tempo domani?”

“Bada ai fatti tuoi,” disse l’orco “saranno più teneri da mangiare.”

“Ma hai già tanta di quella carne,” ribatté la moglie “non ti manca certo: ecco lì un vitello, due pecore e mezzo maiale.”

L’orco disse: “È vero, rimpinzali bene così che non dimagriscano e mettili a letto.”

La brava donna ne fu molto contenta e diede loro una buona cena, ma erano così spaventati che non riuscirono a mangiare un boccone. Quanto all’orco, ricominciò a bere, ben felice di avere l’occorrente da offrire agli amici. Bevve una dozzina di bicchieri più del solito, che gli diede alla testa o lo costrinse ad andare a letto.

L’orco aveva sette figlie, tutte bambine, e queste giovani orchesse avevano tutte una bellissima carnagione perché erano solite mangiare carne fresca come il padre, ma avevano piccoli occhi grigi e rotondi, il naso a becco, lunghi denti affilati e distanti l’uno dall’altro. Non erano ancora cattive, ma promettevano bene perché già mordevano i bambini per succhiare loro il sangue.

Erano andate a letto presto, ognuna con una corona d’oro sulla testa. Nella stessa camera c’era un letto di uguale grandezza e fu in esso che la moglie dell’orco mise i sette bambini, dopodiché andò a letto con il marito.

Pollicino, il quale aveva notato che le figlie dell’orco avevano corone d’oro sulla testa e temeva che l’orco si pentisse di non averli uccisi, si alzò verso mezzanotte e, prendendo i berretti dei fratelli e il proprio, andò pian piano a metterli sulle teste delle sette piccole orchesse, dopo aver tolto le corone d’oro che mise sulla propria testa e su quelle dei fratelli, così che l’orco li scambiasse per le proprie figlie e le figlie per i bambini che voleva uccidere.

Tutto andò come lui pensava perché l’orco, svegliandosi verso mezzanotte e dispiaciuto di aver rimandato al mattino ciò che avrebbe dovuto fare quella notte, si gettò rapidamente fuori dal letto e, afferrando il grosso coltello, disse:

“Andiamo a vedere che fanno quelle piccolo canaglie e facciamola finita.”

Allora salì brancolando nella camera delle bambine e, avvicinandosi al letto in cui si trovavano i bambini, i quali erano tutti addormentati tranne Pollicino, terribilmente spaventato quando sentì che l’orco gli tastava la testa, come già aveva fatto con quelle dei fratelli, disse, sentendo le corone d’oro:

“Stavo per farla bella, in verità; stanotte ho bevuto troppo.”

Allora andò presso il letto in cui giacevano le bambine e, avendo tastato i berretti dei bambini, disse:

“Ragazzacci, siete qui? Facciamo ciò che dobbiamo.”

E con queste parole, senza ulteriore indugio, tagliò le gole delle sue sette figlie.

Compiaciuto per ciò che aveva fatto, andò di nuovo a letto da sua moglie. Appena Pollicino udì l’orco che russava, svegliò i fratelli e disse loro di vestirsi e di seguirlo. Sgattaiolarono giù in giardino e scavalcarono il muro. Corsero tutta la notte, tremando, senza sapere dove stessero andando.

Quando l’orco si svegliò, disse alla moglie: “Vai di sopra e sistema quei giovani mascalzoni arrivati qui ieri sera.”

La donna fu molto sorpresa dalla bontà del marito, non immaginando in che modo dovesse sistemarli; pensando che le avesse ordinato di andare su e fargli indossare i vestiti, salì e rimase sconvolta quando si accorse delle sette figlie uccise e immerse nel sangue.

Svenne, perché questo è il primo espediente al quale ricorrono tutte le donne in casi simili. L’orco, temendo che la moglie si dilungasse troppo nel fare ciò che le aveva ordinato, salì ad aiutarla. Alla vista dell’orribile spettacolo non rimase meno sconvolto di sua moglie.

“Che cosa ho fatto?” gridò “quei maledetti la pagheranno immediatamente.”

Gettò una brocca d’acqua sul viso della moglie e, fattala riprendere, le disse:

“Dammi subito gli stivali delle sette leghe che devo andare a catturarli.”

Partì e dopo aver percorso un bel po’ di strada, andando qua e là, infine imboccò proprio quella su cui erano i poveri bambini, che si trovavano a nemmeno cento passi dalla casa del padre. Videro l’orco che con un passo andava da una montagna all’altra e attraversava i fiumi facilmente come se fossero i più esigui fossi. Pollicino, vedendo una roccia cava vicino al luogo in cui si trovavano, vi fece nascondere i fratelli e vi si infilò lui stesso, badando sempre a ciò che avrebbe fatto l’orco.

L’orco, che si sentiva molto stanco per il lungo e inutile viaggio (perché gli stivali delle sette leghe affaticavano molto chi li indossava) pensò di riposarsi e, guarda un po’, andò a sedere vicino alla roccia in cui si erano nascosti i bambini.

Non potendo essere più stanco di così, si addormentò e, dopo aver riposato per un po’ di tempo, cominciò a russare così spaventosamente che i poveri bambini non furono meno impauriti di quando aveva afferrato il grosso coltello e stava per tagliare loro la gola. Pollicino non era tanto spaventato quanto i fratelli e disse loro che dovevano correre via immediatamente verso casa mentre l’orco era addormentato così profondamente, senza preoccuparsi di lui. Seguirono il suo consiglio e furono rapidamente a casa. Pollicino si avvicinò all’orco, gli sfilò delicatamente gli stivali e se li infilò sulle gambe. Gli stivali erano molti lunghi e larghi, ma siccome erano magici, avevano il potere di farsi grandi e piccoli secondo le gambe che li indossavano; così si adattarono ai suo piedi e alle sue gambe come se fossero stati fatti apposta per lui. Andò immediatamente a casa dell’orco, in cui vide la moglie piangere amaramente per la perdita delle figlie uccise dall’orco.

Pollicino disse: “Vostro marito si trova in grande pericolo perché è stato catturato da una banda di ladri che hanno giurato di ucciderlo se non darà loro tutto il suo oro e il suo argento. Proprio nel momento in cui gli stavano appoggiando i pugnali sulla gola, lui mi ha visto e mi ha chiesto di venire a dirvi in che condizioni si trova e che dovete darmi tutte le cose di valore che possiede, senza tenere nulla altrimenti lo uccideranno senza pietà; siccome la situazione è urgente, ha voluto che indossassi i suoi stivali… vedete che li ho ai piedi… così che io potessi fare più in fretta e dimostrarvi che non mi voglio approfittare.”

La brava donna, troppo impaurita, gli diede tutto ciò che possedeva perché l’orco era un buon marito, sebbene fosse solito mangiare i bambini. Pollicino, avendo preso tutte le ricchezze dell’orco, tornò a casa del padre in cui fu ricevuto con grande gioia.

Ci sono molte persone che non sono d’accordo su questo fatto e fingono che Pollicino non abbia mai derubato l’orco, e che il solo pensarlo sarebbe una grossa ingiustizia, e in tutta coscienza avesse portato via gli stivali delle sette leghe perché gli servivano solo per correre dietro ai bambini. Queste persone affermano di esserne molto certi e persino di essersi trovate spesso a mangiare e a bere a casa del taglialegna. Dichiarano che quando ebbe preso all’orco gli stivali delle sette leghe, andò a corte dove sapeva che fossero molto in ansia per un certo esercito, che si trovava a duecento leghe di distanza, e per l’esito della battaglia. Dissero che andò dal re e gli riferì che, se lo desiderava, gli avrebbe portato notizie dell’esercito prima di notte.

Il re gli promise una grossa somma di denaro a questa condizione. Pollicino fu di parola e ritorno quella notte stessa con le notizie; avendolo reso famoso questa sua prima spedizione, poté chiedere tutto ciò che voleva perché il re lo pagava assai bene per portare ordini all’esercito. Dopo aver fatto il mestiere di messaggero per un po’ di tempo e aver messo insieme una gran ricchezza, tornò a casa dal padre e lì è impossibile esprimere la gioia di tutti per il suo ritorno. Rese facile la vita a tutta la famiglia, comprò incarichi per il padre e i fratelli e, in questo modo, li sistemò assai confortevolmente mentre dal canto proprio fece alla perfezione l’uomo di corte.

Charles Perrault.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)