Snow-White and Red-Rose

(MP3-12' 24'')

A poor widow once lived in a little cottage with a garden in front of it, in which grew two rose trees, one bearing white roses and the other red. She had two children, who were just like the two rose trees; one was called Snow-white and the other Rose-red, and they were the sweetest and best children in the world, always diligent and always cheerful; but Snow-white was quieter and more gentle than Rose-red. Rose-red loved to run about the fields and meadows, and to pick flowers and catch butterflies; but Snow-white sat at home with her mother and helped her in the household, or read aloud to her when there was no work to do. The two children loved each other so dearly that they always walked about hand in hand whenever they went out together, and when Snow-white said, “We will never desert each other,” Rose-red answered: “No, not as long as we live”; and the mother added: “Whatever one gets she shall share with the other.” They often roamed about in the woods gathering berries and no beast offered to hurt them; on the contrary, they came up to them in the most confiding manner; the little hare would eat a cabbage leaf from their hands, the deer grazed beside them, the stag would bound past them merrily, and the birds remained on the branches and sang to them with all their might.

No evil ever befell them; if they tarried late in the wood and night overtook them, they lay down together on the moss and slept till morning, and their mother knew they were quite safe, and never felt anxious about them. Once, when they had slept all night in the wood and had been wakened by the morning sun, they perceived a beautiful child in a shining white robe sitting close to their resting-place. The figure got up, looked at them kindly, but said nothing, and vanished into the wood. And when they looked round about them they became aware that they had slept quite close to a precipice, over which they would certainly have fallen had they gone on a few steps further in the darkness. And when they told their mother of their adventure, she said what they had seen must have been the angel that guards good children.

Snow-white and Rose-red kept their mother’s cottage so beautifully clean and neat that it was a pleasure to go into it. In summer Rose-red looked after the house, and every morning before her mother awoke she placed a bunch of flowers before the bed, from each tree a rose. In winter Snow-white lit the fire and put on the kettle, which was made of brass, but so beautifully polished that it shone like gold. In the evening when the snowflakes fell their mother said: “Snow-white, go and close the shutters,” and they drew round the fire, while the mother put on her spectacles and read aloud from a big book and the two girls listened and sat and span. Beside them on the ground lay a little lamb, and behi

nd them perched a little white dove with its head tucked under its wings.

One evening as they sat thus cosily together someone knocked at the door as though he desired admittance. The mother said: “Rose-red, open the door quickly; it must be some traveler seeking shelter.” Rose-red hastened to unbar the door, and thought she saw a poor man standing in the darkness outside; but it was no such thing, only a bear, who poked his thick black head through the door. Rose-red screamed aloud and sprang back in terror, the lamb began to bleat, the dove flapped its wings, and Snow-white ran and hid behind her mother’s bed. But the bear began to speak, and said: “Don’t be afraid: I won’t hurt you. I am half frozen, and only wish to warm myself a little.” “My poor bear,” said the mother, “lie down by the fire, only take care you don’t burn your fur.” Then she called out: “Snow-white and Rose-red, come out; the bear will do you no harm; he is a good, honest creature.” So they both came out of their hiding-places, and gradually the lamb and dove drew near too, and they all forgot their fear. The bear asked the children to beat the snow a little out of his fur, and they fetched a brush and scrubbed him till he was dry.

Then the beast stretched himself in front of the fire, and growled quite happily and comfortably. The children soon grew quite at their ease with him, and led their helpless guest a fearful life. They tugged his fur with their hands, put their small feet on his back, and rolled him about here and there, or took a hazel wand and beat him with it; and if he growled they only laughed. The bear submitted to everything with the best possible good-nature, only when they went too far he cried: “Oh! children, spare my life!

blockquote> Snow-white and Rose-red,

Don’t beat your lover dead.”

When it was time to retire for the night, and the others went to bed, the mother said to the bear: “You can lie there on the hearth, in heaven’s name; it will be shelter for you from the cold and wet.” As soon as day dawned the children led him out, and he trotted over the snow into the wood. From this time on the bear came every evening at the same hour, and lay down by the hearth and let the children play what pranks they liked with him; and they got so accustomed to him that the door was never shut till their black friend had made his appearance.

When spring came, and all outside was green, the bear said one morning to Snow-white: “Now I must go away, and not return again the whole summer.” “Where are you going to, dear bear?” asked Snow-white. “I must go to the wood and protect my treasure from the wicked dwarfs. In winter, when the earth is frozen hard, they are obliged to remain underground, for they can’t work their way through; but now, when the sun has thawed and warmed the ground, they break through and come up above to spy the land and steal what they can; what once falls into their hands and into their caves is not easily brought back to light.” Snow-white was quite sad over their friend’s departure, and when she unbarred the door for him, the bear, stepping out, caught a piece of his fur in the door-knocker, and Snow-white thought she caught sight of glittering gold beneath it, but she couldn’t be certain of it; and the bear ran hastily away, and soon disappeared behind the trees.

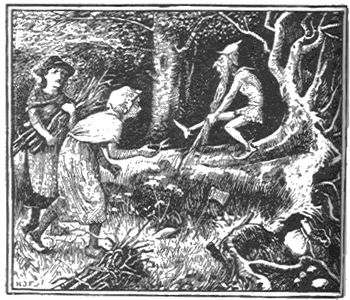

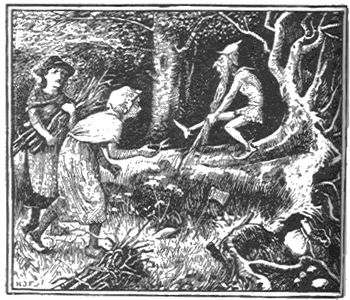

A short time after this the mother sent the children into the wood to collect fagots. They came in their wanderings upon a big tree which lay felled on the ground, and on the trunk among the long grass they noticed something jumping up and down, but what it was they couldn’t distinguish. When they approached nearer they perceived a dwarf with a wizened face and a beard a yard long. The end of the beard was jammed into a cleft of the tree, and the little man sprang about like a dog on a chain, and didn’t seem to know what he was to do. He glared at the girls with his fiery red eyes, and screamed out: “What are you standing there for? Can’t you come and help me?” “What were you doing, little man?” asked Rose-red. “You stupid, inquisitive goose!” replied the dwarf; “I wanted to split the tree, in order to get little chips of wood for our kitchen fire; those thick logs that serve to make fires for coarse, greedy people like yourselves quite burn up all the little food we need. I had successfully driven in the wedge, and all was going well, but the cursed wood was so slippery that it suddenly sprang out, and the tree closed up so rapidly that I had no time to take my beautiful white beard out, so here I am stuck fast, and I can’t get away; and you silly, smooth-faced, milk-and-water girls just stand and laugh! Ugh! what wretches you are!”

The children did all in their power, but they couldn’t get the beard out; it was wedged in far too firmly. “I will run and fetch somebody,” said Rose-red. “Crazy blockheads!” snapped the dwarf; “what’s the good of calling anyone else? You’re already two too many for me. Does nothing better occur to you than that?” “Don’t be so impatient,” said Snow-white, “I’ll see you get help,” and taking her scissors out of her pocket she cut off the end of his beard.

As soon as the dwarf felt himself free he seized a bag full of gold which was hidden among the roots of the tree, lifted it up, and muttered aloud: “Curse these rude wretches, cutting off a piece of my splendid beard!” With these words he swung the bag over his back, and disappeared without as much as looking at the children again.

Shortly after this Snow-white and Rose-red went out to get a dish of fish. As they approached the stream they saw something which looked like an enormous grasshopper springing toward the water as if it were going to jump in. They ran forward and recognized their old friend the dwarf. “Where are you going to?” asked Rose-red; “you’re surely not going to jump into the water?” “I’m not such a fool,” screamed the dwarf. “Don’t you see that cursed fish is trying to drag me in?” The little man had been sitting on the bank fishing, when unfortunately the wind had entangled his beard in the line; and when immediately afterward a big fish bit, the feeble little creature had no strength to pull it out; the fish had the upper fin, and dragged the dwarf toward him. He clung on with all his might to every rush and blade of grass, but it didn’t help him much; he had to follow every movement of the fish, and was in great danger of being drawn into the water. The girls came up just at the right moment, held him firm, and did all they could to disentangle his beard from the line; but in vain, beard and line were in a hopeless muddle. Nothing remained but to produce the scissors and cut the beard, by which a small part of it was sacrificed.

When the dwarf perceived what they were about he yelled to them: “Do you call that manners, you toad-stools! to disfigure a fellow’s face? It wasn’t enough that you shortened my beard before, but you must now needs cut off the best bit of it. I can’t appear like this before my own people. I wish you’d been in Jericho first.” Then he fetched a sack of pearls that lay among the rushes, and without saying another word he dragged it away and disappeared behind a stone.

It happened that soon after this the mother sent the two girls to the town to buy needles, thread, laces, and ribbons. Their road led over a heath where huge boulders of rock lay scattered here and there. While trudging along they saw a big bird hovering in the air, circling slowly above them, but always descending lower, till at last it settled on a rock not far from them. Immediately afterward they heard a sharp, piercing cry. They ran forward, and saw with horror that the eagle had pounced on their old friend the dwarf, and was about to carry him off. The tender-hearted children seized hold of the little man, and struggled so long with the bird that at last he let go his prey. When the dwarf had recovered from the first shock he screamed in his screeching voice: “Couldn’t you have treated me more carefully? You have torn my thin little coat all to shreds, useless, awkward hussies that you are!” Then he took a bag of precious stones and vanished under the rocks into his cave. The girls were accustomed to his ingratitude, and went on their way and did their business in town. On their way home, as they were again passing the heath, they surprised the dwarf pouring out his precious stones on an open space, for he had thought no one would pass by at so late an hour. The evening sun shone on the glittering stones, and they glanced and gleamed so beautifully that the children stood still and gazed on them. “What are you standing there gaping for?” screamed the dwarf, and his ashen-gray face became scarlet with rage. He was about to go off with these angry words when a sudden growl was heard, and a black bear trotted out of the wood. The dwarf jumped up in great fright, but he hadn’t time to reach his place of retreat, for the bear was already close to him. Then he cried in terror: “Dear Mr. Bear, spare me! I’ll give you all my treasure. Look at those beautiful precious stones lying there. Spare my life! what pleasure would you get from a poor feeble little fellow like me? You won’t feel me between your teeth. There, lay hold of these two wicked girls, they will be a tender morsel for you, as fat as young quails; eat them up, for heaven’s sake.” But the bear, paying no attention to his words, gave the evil little creature one blow with his paw, and he never moved again.

The girls had run away, but the bear called after them: “Snow-white and Rose-red, don’t be afraid; wait, and I’ll come with you.” Then they recognized his voice and stood still, and when the bear was quite close to them his skin suddenly fell off, and a beautiful man stood beside them, all dressed in gold.

“I am a king’s son,” he said, “and have been doomed by that unholy little dwarf, who had stolen my treasure, to roam about the woods as a wild bear till his death should set me free. Now he has got his well-merited punishment.”

Snow-white married him, and Rose-red his brother, and they divided the great treasure the dwarf had collected in his cave between them. The old mother lived for many years peacefully with her children; and she carried the two rose trees with her, and they stood in front of her window, and every year they bore the finest red and white roses.

Grimm.

Biancaneve e Rosarossa

C’era una volta una povera vedova che viveva in una casetta con davanti un giardino nel quale crescevano due piante di rose, uno che produceva rose bianche e l’altro rosse. Aveva due figlie che somigliavano proprio alle due piante di rose; una si chiamava Biancaneve e l’altra Rosarossa ed erano le ragazze più dolci e migliori del mondo, sempre diligenti e sempre allegre; ma Biancaneve era più tranquilla e più gentile di Rosarossa. Rosarossa amava correre per i campi e per i prati, raccogliere fiori e catturare farfalle; ma Biancaneve stava a casa con la madre e l’aiutava nelle faccende domestiche o leggeva ad alta voce per lei quando non c’erano lavori da svolgere. Le due ragazze si amavano l’un l’altra così teneramente che camminavano sempre mano nella mano ogni volta in cui uscivano insieme e quando Biancaneve diceva: “Non ci lasceremo mai l’un l’altra.”, Rosarossa rispondeva: “No, per tutta la vita.” e la madre aggiungeva: “Qualsiasi cosa una riceva, la dividerà con l’altra.” Spesso andavano a zonzo per i boschi raccogliendo bacche e non vi era animale che facesse loro del male; al contrario, si avvicinavano loro nella maniera più fiduciosa; il leprotto mangiava una foglia di cavolo dalle loro mani, il daino pascolava accanto a loro, il cervo saltava allegramente vicino a loro e gli uccelli restavano sui rami e cantavano per loro con tutte le energie.

Non era mai accaduto loro niente di male; se facevano tardi nel bosco e la notte le sorprendeva, si sdraiavano insieme sul muschio e dormivano fino al mattino e la loro madre sapeva che erano completamente al sicuro e non era mai in ansia per loro. Una volta, dopo che avevano dormito per tutta la notte nel bosco e si erano svegliate con il sole del mattino, si accorsero di un bellissimo bambino con un abito bianco splendente che sedeva vicino al loro giaciglio. La creatura si alzò e le guardò gentilmente, ma non disse nulla e svanì nel bosco. E quando si guardarono intorno, si resero conto di aver dormito proprio sull’orlo di un precipizio, nel quale sarebbero certamente cadute se avessero pochi passi nelle tenebre. Quando narrarono alla madre la loro avventura, lei disse che chi avevano visto doveva essere stato un angelo che veglia i bambini buoni.

Biancaneve e Rosarossa tenevano la casetta della madre così meravigliosamente pulita e ordinata che era un piacere entrarvi. In estate Rosarossa badava alla casa e ogni mattina, prima che la madre si svegliasse, metteva un mazzo di fiori davanti al letto, e da ciascuna pianta una rosa. In inverno Biancaneve accendeva il fuoco e vi metteva sopra un bollitore, che era fatto di ottone ma così meravigliosamente lucido che scintillava come oro. La sera, quando cadevano i fiocchi di neve, la madre diceva: “Biancaneve, vai a chiudere le persiane.” e si avvicinavano al fuoco, mentre la madre indossava gli occhiali e leggeva a voce alta da un grosso libro e le due ragazze ascoltavano e sedevano a filare. Per terra accanto a loro giaceva un agnellino e dietro stava appollaiata una piccola colomba con la testa nascosta sotto le ali.

Una sera in cui sedevano tutte e due insieme a loro agio, qualcuno bussò alla porta come se desiderasse entrare. La madre disse: “Rosarossa, svelta, apri la porta; deve essere un viandante in cerca di riparo.” Rosarossa si affrettò a togliere il catenaccio alla porta e pensò di vedere un pover’uomo che stava fuori nelle tenebre; ma non era niente del genere, era solo un orso che infilò la folta testa nera attraverso la porta. Rosarossa strillò e balzò all’indietro terrorizzata, l’agnello cominciò a belare, la colomba sbatté le ali e Biancaneve corse a nascondersi dietro il letto della madre. Ma l’orso cominciò a parlare e disse: “Non abbiate paura: non voglio farvi del male. Sono mezzo congelato e desidero solo scaldarmi un po’.” “Mio povero orso,” disse la madre, “sdraiati accanto al fuoco, bada solo che la tua pelliccia non bruci.” “Poi gridò:” Biancaneve e Rosarossa, venite fuori; l’orso non vi farà del male; è una creatura buona e schietta.” così uscirono entrambe dai loro nascondigli e pian piano anche l’agnello e la colomba si avvicinarono e tutti dimenticarono la paura. l’orso chiese alle ragazze di scuotere via la neve dalla sua pelliccia e loro presero uno spazzolone e lo strofinarono finché fu asciutto.

Poi l’animale si distese davanti al fuoco e mugolò felice e tranquillo. Le ragazze ben presto si sentirono a loro agio con lui e presero confidenza con il loro indifeso ospite. Gli tiravano la pelliccia con le mani, gli mettevano i piedini sul dorso, lo rotolavano di qua e di là o prendevano un bastoncino di nocciolo e lo picchiavano con esso; e ridevano, se lui mugolava. L’orso si assoggettava a tutto col miglior buon carattere, solo quando si spingevano un po’ troppo in là, gridava: “Ragazze, risparmiatemi la vita!”

Biancaneve e Rosarossa,

non mettete chi vi ama nella fossa.”

Quando fu l’ora di ritirarsi per la notte, e gli altri furono andati a dormire, la madre disse all’orso: “Puoi sdraiarti qua per terra, in nome del cielo; ci sarà un riparo per te dal freddo e dalla pioggia.” Appena si fece giorno, le ragazze lo condussero fuori e lui trotterellò nella neve dentro il bosco. Da quel momento l’orso venne ogni sera alla medesima ora e si sdraiava per terra e lasciava che le ragazze gli facessero tutte le monellerie che volevano; e loro si erano così abituate a lui che la porta non veniva mai chiusa finché il loro amico nero non faceva la sua comparsa.

Quando giunse la primavera e tutto all’esterno era verde, una mattina l’orso disse a Biancaneve: “Adesso devo andare via e non tornerò per tutta l’estate.” “Dove stai andando, caro orso?” chiese Biancaneve. “Devo andare nel bosco a proteggere il mio tesoro dai malvagi gnomi. In inverno, quando il terreno è gelato, sono costretti a rimanere sottoterra perchè non possono farsi strada; ma adesso, quando il sole ha sgelato e scaldato il terreno, loro sbucano fuori e vengono in superficie a spiare la terra e a rubare quel che possono; una volta che qualcosa cade nelle loro mani e nelle loro caverne, non è facile riportarla alla luce.” Biancaneve era molto triste per la partenza dell’amico e quando tolse il catenaccio alla porta per lui, l’orso, uscendo, lasciò un pezzetto di pelliccia sul batacchio e Biancaneve credette di vedere sotto uno scintillio d’oro, ma non poteva esserne certa; l’orso corse via in fretta e ben presto scomparve dietro gli alberi.

Un po’ di tempo dopo la madre mandò le ragazze nel bosco a raccogliere fascine. Nel loro girovagare giunsero presso un grosso albero che giaceva abbattuto sul terreno e sul tronco, tra l’erba alta, notarono qualcosa che saltava su e giù, ma non riuscivano a distinguere che cosa fosse. Quando si fecero più vicine, si accorsero che era uno gnomo dal viso raggrinzito e con la barba lunga una iarda. L’estremità della barba era intrappolata in una fessura dell’albero e l’ometto si dimenava come un cane alla catena e sembrava non sapere che fare. Fissò sulle ragazze i fiammeggianti occhi rossi e strillò: “Che state lì a fare? Non potete venire ad aiutarmi?” “Che cosa stavi facendo, ometto?” chiese Rosarossa. “Stupida oca curiosa!” ribatté lo gnomo, “Volevo spaccare l’albero per farne piccole schegge di legna per il fuoco della nostra cucina; quei grossi ciocchi che servono a fare fuoco per la gente grossolana e ingorda come voi bruciano tutto il piccolo cibo di cui abbiamo bisogno. Ero già riuscito a ficcare il cuneo e tutto stava andando bene, ma questo legno maledetto era così scivoloso che improvvisamente è saltato via e l’albero si è chiuso così rapidamente che non ho avuto il tempo di di tirare via la mia splendida barba bianca, così sono rimasto preso e non posso liberarmi; e voi sciocche ragazze dalla faccia liscia e all’acqua di rose sapete solo star lì a ridere! Ugh! Sciagurate che non siete altro!”

Le ragazze fece tutto ciò che poterono, ma non ce la fecero a liberare la barba; era incastrata troppo saldamente. “Correrò a prendere qualcuno.” disse Rosarossa. “Pazza testa di legno!” sbottò lo gnomo “A che pro chiamare qualcun altro? Voi due siete già troppo per me. Non vi viene in mente niente di meglio?” “Non essere così impaziente,” disse Biancaneve “vedrò di aiutarti.” e prendendo dalla tasca le forbici, gli tagliò l’estremità della barba.

Appena lo gnomo fu libero, afferrò una borsa piena d’oro che aveva nascosta fra le radici dell’albero, la sollevò e bofonchiò a voce alta: “Maledette queste villane screanzate, che hanno tagliato un pezzo della mia splendida barba!” Con queste parole si gettò la borsa sul dorso e sparì senza neppure un’altra occhiata alle ragazze.

Dopo un po’ di tempo Biancaneve e Rosarossa andarono a procurarsi un piatto di pesce. Mentre si avvicinavano al ruscello, videro qualcosa che sembrava un’enorme cavalletta balzare verso l’acqua come se volesse saltarvi dentro. Corsero avanti e riconobbero il loro vecchio amico, lo gnomo. “Dove stai andando?” chiese Rosarossa, “Di certo non vorrai saltare nell’acqua?” “Non sono così sciocco,” strillò lo gnomo “Non vedete che quel maledetto pesce sta cercando di trascinarmi dentro?” L’ometto era seduto sulla riva a pescare quando sfortunatamente il vento gli aveva impigliato la barba nella lenza; e quando immediatamente dopo un pesce aveva abboccato, la debole creaturina non era stata in grado di tirarlo fuori; il pesce aveva avuto la meglio e stava trascinando con sé lo gnomo. Lui si era afferrato con tutte le forze a ogni giunco e filo d’erba, ma non gli era stato d’aiuto; doveva seguire ogni movimento del pesce e rischiava di essere trascinato in acqua. Le ragazze erano arrivate al momento giusto, lo afferrarono saldamente e fecero tutto ciò che poterono per districare la barba dalla lenza; invano, barba e lenza erano un pasticcio senza speranza. Non restava altro da fare che tirar fuori le forbici e tagliare la barba, e una piccola parte di essa fu sacrificata.

Quando lo gnomo se ne accorse, gridò loro: “È questo il modo di sfiguarere una bella faccia, brutti rospi? Non era stato abbastanza avermi accorciato prima la barba, ora dovevate tagliarne la parte migliore. Non posso comparire così davanti alla mia gente, andate a farvi benedire!” Poi afferrò un sacco di perle che giaceva tra i giunchi, lo trascinò via senza dire una parola e sparì dietro una pietra.

Dopo un po’ di tempo da ciò, accadde che la madre mandasse le due ragazze in città a comprare aghi, filo, lacci e nastri. La strada le condusse attraverso una brughiera sulla quale grossi macigni giacevano sparsi qua e là. Mentre arrancavano in avanti videro un grosso uccello che si librava nell’aria, volando lentamente in cerchio sopra di loro, e scendendo sempre più in basso finché alla fine si posò su una roccia non lontana da loro. Immediatamente dopo sentirono un grido acuto e penetrante. Corsero avanti e videro con orrore che l’aquila si era avventata sul loro vecchio amico gnomo e stava per portarlo via. Le due ragazze dal cuore tenero afferrarono lo gnomo e lottarono così a lungo con l’uccello che alla fine lasciò la preda. Quando lo gnomo si fu ripreso dallo spavento iniziale, strillò con la sua voce stridula: “Non potevate trattarmi con maggior attenzione? Avete lacerato il mio piccolo corsetto, fatto a brandelli, reso inservibile, maldestre ragazze sfacciate che non siete altro!” poi prese una borsa di pietre preziose e svanì sotto le rocce dentro la sua caverna. Le ragazze erano abituate alla sua ingratitudine e andarono per la loro strada e fecero le loro commissioni in città. Sulla strada del ritorno verso casa, mentre stavano attraversando di nuovo la brughiera, sosrpresero lo gnomo che stava sparpagliando le sue pietre preziose in uno spazio aperto perché non aveva pensato che qualcuno potesse ancora passare a un’ora così tarda. Il sole al tramonto brillava sulle pietre lucenti e queste luccicavano e scintillavano così meravigliosamente che le ragazze rimasero immobili a fissarle. “Che cosa state facendo lì a bocca aperta?” strillò lo gnomo e la sua faccia livida si fece scarlatta per la collera. Stava per andarsene con queste parole rabbiose quando improvvisamente si sentì un ringhio e un orso nero trotterellò fuori dal bosco. Lo gnomo saltò per il grande spavento, ma non ebbe modo di raggiungere il suo nascondiglio perché l’orso era già vicino a lui. Allora gridò terrorizzato: “Caro signor orso, risparmiatemi! Vi darò tutto il mio tesoro. Guardate quelle magnifiche pietre preziose sparpagliate là. Risparmiate la mia vita! Che gusto vi darebbe un povero esserino debole come me? Nemmeno mi sentireste tra i denti. Là, prendete quelle due malvage ragazze, saranno un tenero boccone per voi, grasse come giovani quaglie; mangiate loro, per amor del cielo.” ma l’orso, senza prestare attenzione alle sue parole, diede un colpo con la zampa alla piccola creatura mlavagia, che non si mosse più.

Le ragazze erano corse via, ma l’orso le richiamò: “Biancaneve e Rosarossa, non abbiate paura; aspettate e verrà con voi.” allora riconobbero la sua voce e rimasero immobili, e quando l’orso fu abbastanza vicino, improvvisamente la pelliccia gli cadde di dosso e davanti a loro rimase un bellissimo giovane tutto vestito d’oro.

“Sono il figlio di un re,” disse “e sono stato condannato da quello scellerato piccolo gnomo, il quale ha rubato il mio tesoro, a vagabondare per i boschi sottoforma di orso selvatico finché la sua morte non mi avesse liberato. Adesso ha avuto il ben meritato castigo.”

Biancaneve sposò il principe e Rosarossa suo fratello e divisero tra loro il grande tesoro che lo gnomo aveva accumulato nella sua caverna. La vecchia madre visse in santa pace per molti anni con le sue ragazze; portò con sé due piante di rose che stavano davanti alla sua finestra e ogni anno davano le più belle rose rosse e bianche.

Fratelli Grimm.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)