A Voyage to Lilliput

(MP3-41' 35'')

CHAPTER I

My father had a small estate in Nottinghamshire, and I was the third of four sons. He sent me to Cambridge at fourteen years old, and after studying there three years I was bound apprentice to Mr. Bates, a famous surgeon in London. There, as my father now and then sent me small sums of money, I spent them in learning navigation, and other arts useful to those who travel, as I always believed it would be some time or other my fortune to do.

Three years after my leaving him my good master, Mr. Bates, recommended me as ship’s surgeon to the “Swallow,” on which I voyaged three years. When I came back I settled in London, and, having taken part of a small house, I married Miss Mary Burton, daughter of Mr. Edmund Burton, hosier.

But my good master Bates died two years after; and as I had few friends my business began to fail, and I determined to go again to sea. After several voyages, I accepted an offer from Captain W. Pritchard, master of the “Antelope,” who was making a voyage to the South Sea. We set sail from Bristol, May 4, 1699; and our voyage at first was very prosperous.

But in our passage to the East Indies we were driven by a violent storm to the north-west of Van Diemen’s Land. Twelve of our crew died from hard labor and bad food, and the rest were in a very weak condition. On the 5th of November, the weather being very hazy, the seamen spied a rock within 120 yards of the ship; but the wind was so strong that we were driven straight upon it, and immediately split. Six of the crew, of whom I was one, letting down the boat, got clear of the ship, and we rowed about three leagues, till we could work no longer. We therefore trusted ourselves to the mercy of the waves; and in about half an hour the boat was upset by a sudden squall. What became of my companions in the boat, or those who escaped on the rock or were left in the vessel, I cannot tell; but I conclude they were all lost. For my part, I swam as fortune directed me, and was pushed forward by wind and tide; but when I was able to struggle no longer I found myself within my depth. By this time the storm was much abated. I reached the shore at last, about eight o’clock in the evening, and advanced nearly half a mile inland, but could not discover any sign of inhabitants. I was extremely tired, and with the heat of the weather I found myself much inclined to sleep. I lay down on the grass, which was very short and soft, and slept sounder than ever I did in my life for about nine hours. When I woke, it was just daylight. I attempted to rise, but could not; for as I happened to be lying on my back, I found my arms and legs were fastened on each side to the ground; and my hair, which was long and thick, tied down in the same manner. I could only look upward. The sun began to grow hot, and the light hurt my eyes. I heard a confused noise about me, but could see nothing except the sky. In a little time I felt something alive and moving on my left leg, which, advancing gently over my breast, came almost up to my chin, when, bending my eyes downward, I perceived it to be a human creature, not six inches high, with a bow and arrow in his hands, and a quiver at his back.

In the meantime I felt at least forty more following the first. I was in the utmost astonishment, and roared so loud that they all ran back in a fright; and some of them were hurt with the falls they got by leaping from my sides upon the ground. However, they soon returned, and one of them, who ventured so far as to get a full sight of my face, lifted up his hands in admiration. I lay all this while in great uneasiness; but at length, struggling to get loose, I succeeded in breaking the strings that fastened my left arm to the ground; and at the same time, with a violent pull that gave me extreme pain, I a little loosened the strings that tied down my hair, so that I was just able to turn my head about two inches. But the creatures ran off a second time before I could seize them, whereupon there was a great shout, and in an instant I felt above a hundred arrows discharged on my left hand, which pricked me like so many needles. Moreover, they shot another flight into the air, of which some fell on my face, which I immediately covered with my left hand. When this shower of arrows was over I groaned with grief and pain, and then, striving again to get loose, they discharged another flight of arrows larger than the first, and some of them tried to stab me with their spears; but by good luck I had on a leather jacket, which they could not pierce. By this time I thought it most prudent to lie still till night, when, my left hand being already loose, I could easily free myself; and as for the inhabitants, I thought I might be a match for the greatest army they could bring against me if they were all of the same size as him I saw. When the people observed that I was quiet they discharged no more arrows, but by the noise I heard I knew that their number was increased; and about four yards from me, for more than an hour, there was a knocking, like people at work. Then, turning my head that way as well as the pegs and strings would let me, I saw a stage set up, about a foot and a half from the ground, with two or three ladders to mount it. From this, one of them, who seemed to be a person of quality, made me a long speech, of which I could not understand a word, though I could tell from his manner that he sometimes threatened me, and sometimes spoke with pity and kindness. I answered in few words, but in the most submissive manner; and, being almost famished with hunger, I could not help showing my impatience by putting my finger frequently to my mouth, to signify that I wanted food. He understood me very well, and, descending from the stage, commanded that several ladders should be set against my sides, on which more than a hundred of the inhabitants mounted, and walked toward my mouth with baskets full of food, which had been sent by the King’s orders when he first received tidings of me. There were legs and shoulders like mutton but smaller than the wings of a lark. I ate them two or three at a mouthful, and took three loaves at a time. They supplied me as fast as they could, with a thousand marks of wonder at my appetite. I then made a sign that I wanted something to drink. They guessed that a small quantity would not suffice me, and, being a most ingenious people, they slung up one of their largest hogsheads, then rolled it toward my hand, and beat out the top. I drank it off at a draught, which I might well do, for it did not hold half a pint. They brought me a second hogshead, which I drank, and made signs for more; but they had none to give me. However, I could not wonder enough at the daring of these tiny mortals, who ventured to mount and walk upon my body, while one of my hands was free, without trembling at the very sight of so huge a creature as I must have seemed to them. After some time there appeared before me a person of high rank from his Imperial Majesty. His Excellency, having mounted my right leg, advanced to my face, with about a dozen of his retinue, and spoke about ten minutes, often pointing forward, which, as I afterward found, was toward the capital city, about half a mile distant, whither it was commanded by his Majesty that I should be conveyed. I made a sign with my hand that was loose, putting it to the other (but over his Excellency’s head, for fear of hurting him or his train), to show that I desired my liberty. He seemed to understand me well enough, for he shook his head, though he made other signs to let me know that I should have meat and drink enough, and very good treatment. Then I once more thought of attempting to escape; but when I felt the smart of their arrows on my face and hands, which were all in blisters and observed likewise that the number of my enemies increased, I gave tokens to let them know that they might do with me what they pleased. Then they daubed my face and hands with a sweet-smelling ointment, which in a few minutes removed all the smarts of the arrows. The relief from pain and hunger made me drowsy, and presently I fell asleep. I slept about eight hours, as I was told afterward; and it was no wonder, for the physicians, by the Emperor’s orders, had mingled a sleeping draught in the hogsheads of wine.

It seems that, when I was discovered sleeping on the ground after my landing, the Emperor had early notice of it, and determined that I should be tied in the manner I have related (which was done in the night, while I slept), that plenty of meat and drink should be sent me, and a machine prepared to carry me to the capital city. Five hundred carpenters and engineers were immediately set to work to prepare the engine. It was a frame of wood, raised three inches from the ground, about seven feet long and four wide, moving upon twenty-two wheels. But the difficulty was to place me on it. Eighty poles were erected for this purpose, and very strong cords fastened to bandages which the workmen had tied round my neck, hands, body, and legs. Nine hundred of the strongest men were employed to draw up these cords by pulleys fastened on the poles, and in less than three hours I was raised and slung into the engine, and there tied fast. Fifteen hundred of the Emperor’s largest horses, each about four inches and a half high, were then employed to draw me toward the capital. But while all this was done I still lay in a deep sleep, and I did not wake till four hours after we began our journey.

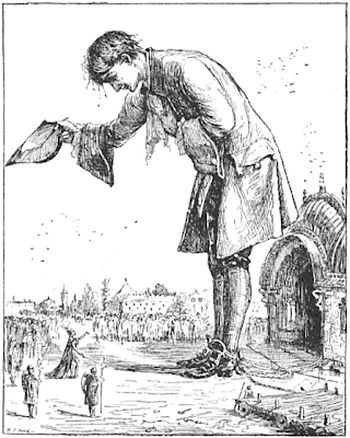

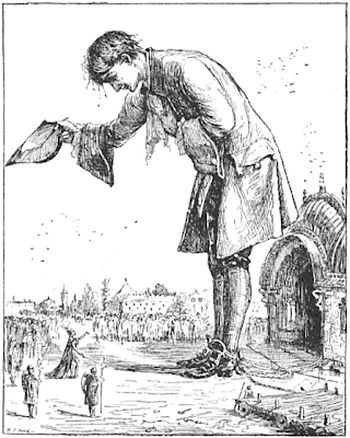

The Emperor and all his Court came out to meet us when we reached the capital; but his great officials would not suffer his Majesty to risk his person by mounting on my body. Where the carriage stopped there stood an ancient temple, supposed to be the largest in the whole kingdom, and here it was determined that I should lodge. Near the great gate, through which I could easily creep, they fixed ninety-one chains, like those which hang to a lady’s watch, which were locked to my left leg with thirty-six padlocks; and when the workmen found it was impossible for me to break loose, they cut all the strings that bound me. Then I rose up, feeling as melancholy as ever I did in my life. But the noise and astonishment of the people on seeing me rise and walk were inexpressible. The chains that held my left leg were about two yards long, and gave me not only freedom to walk backward and forward in a semicircle, but to creep in and lie at full length inside the temple. The Emperor, advancing toward me from among his courtiers, all most magnificently clad, surveyed me with great admiration, but kept beyond the length of my chain. He was taller by about the breadth of my nail than any of his Court, which alone was enough to strike awe into the beholders, and graceful and majestic.

The better to behold him, I lay down on my side, so that my face was level with his, and he stood three yards off. However, I have had him since many times in my hand, and therefore cannot be deceived. His dress was very simple; but he wore a light helmet of gold, adorned with jewels and a plume. He held his sword drawn in his hand, to defend himself if I should break loose; it was almost three inches long, and the hilt was of gold, enriched with diamonds. His voice was shrill, but very clear. His Imperial Majesty spoke often to me, and I answered; but neither of us could understand a word.

CHAPTER II

After about two hours the Court retired, and I was left with a strong guard to keep away the crowd, some of whom had had the impudence to shoot their arrows at me as I sat by the door of my house. But the colonel ordered six of them to be seized and delivered bound into my hands. I put five of them into my coat pocket; and as to the sixth, I made a face as if I would eat him alive. The poor man screamed terribly, and the colonel and his officers were much distressed, especially when they saw me take out my penknife. But I soon set them at ease, for, cutting the strings he was bound with, I put him gently on the ground, and away he ran. I treated the rest in the same manner, taking them one by one out of my pocket; and I saw that both the soldiers and people were delighted at this mark of my kindness.

Toward night I got with some difficulty into my house, where I lay on the ground, as I had to do for a fortnight, till a bed was prepared for me out of six hundred beds of the ordinary measure.

Six hundred servants were appointed me, and three hundred tailors made me a suit of clothes. Moreover, six of his Majesty’s greatest scholars were employed to teach me their language, so that soon I was able to converse after a fashion with the Emperor, who often honored me with his visits. The first words I learned were to desire that he would please to give me my liberty, which I every day repeated on my knees; but he answered that this must be a work of time, and that first I must swear a peace with him and his kingdom. He told me also that by the laws of the nation I must be searched by two of his officers, and that as this could not be done without my help, he trusted them in my hands, and whatever they took from me should be returned when I left the country. I took up the two officers, and put them into my coat pockets. These gentlemen, having pen, ink, and paper about them, made an exact list of everything they saw, which I afterward translated into English, and which ran as follows:

“In the right coat pocket of the great Man-Mountain we found only one great piece of coarse cloth, large enough to cover the carpet of your Majesty’s chief room of state. In the left pocket we saw a huge silver chest, with a silver cover, which we could not lift. We desired that it should be opened, and one of us stepping into it found himself up to the mid-leg in a sort of dust, some of which flying into our faces sent us both into a fit of sneezing. In his right waistcoat pocket we found a number of white thin substances, folded one over another, about the size of three men, tied with a strong cable, and marked with black figures, which we humbly conceive to be writings. In the left there was a sort of engine, from the back of which extended twenty long poles, with which, we conjecture, the Man-Mountain combs his head. In the smaller pocket on the right side were several round flat pieces of white and red metal, of different sizes. Some of the white, which appeared to be silver, were so large and heavy that my comrade and I could hardly lift them. From another pocket hung a huge silver chain, with a wonderful kind of engine fastened to it, a globe half silver and half of some transparent metal; for on the transparent side we saw certain strange figures, and thought we could touch them till we found our fingers stopped by the shining substance. This engine made an incessant noise, like a water-mill, and we conjecture it is either some unknown animal, or the god he worships, but probably the latter, for he told us that he seldom did anything without consulting it. This is a list of what we found about the body of the Man-Mountain, who treated us with great civility.”

I had one private pocket which escaped their search, containing a pair of spectacles and a small spy-glass, which, being of no consequence to the Emperor, I did not think myself bound in honor to discover.

CHAPTER III

My gentleness and good behavior gained so far on the Emperor and his Court, and, indeed, on the people in general, that I began to have hopes of getting my liberty in a short time. The natives came by degrees to be less fearful of danger from me. I would sometimes lie down and let five or six of them dance on my hand; and at last the boys and girls ventured to come and play at hide-and-seek in my hair.

The horses of the army and of the royal stables were no longer shy, having been daily led before me; and one of the Emperor’s huntsmen, on a large courser, took my foot, shoe and all, which was indeed a prodigious leap.

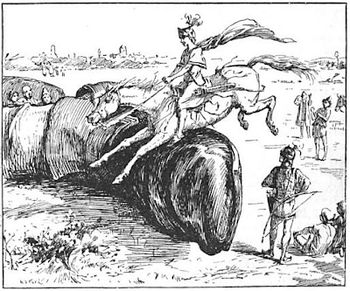

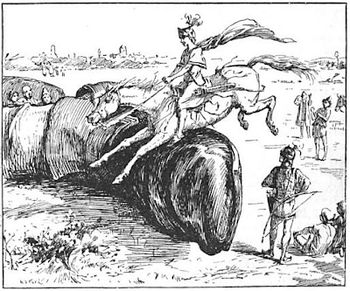

I amused the Emperor one day in a very extraordinary manner. I took nine sticks, and fixed them firmly in the ground in a square. Then I took four other sticks, and tied them parallel at each corner, about two feet from the ground. I fastened my handkerchief to the nine sticks that stood erect, and extended it on all sides till it was as tight as the top of a drum; and I desired the Emperor to let a troop of his best horse, twenty-four in number, come and exercise upon this plain. His majesty approved of the proposal, and I took them up one by one, with the proper officers to exercise them. As soon as they got into order they divided into two parties, discharged blunt arrows, drew their swords, fled and pursued, and, in short, showed the best military discipline I ever beheld. The parallel sticks secured them and their horses from falling off the stage, and the Emperor was so much delighted that he ordered this entertainment to be repeated several days, and persuaded the Empress herself to let me hold her in her chair within two yards of the stage, whence she could view the whole performance. Fortunately no accident happened, only once a fiery horse, pawing with his hoof, struck a hole in my handkerchief, and overthrew his rider and himself. But I immediately relieved them both, and covering the hole with one hand, I set down the troop with the other as I had taken them up. The horse that fell was strained in the shoulder; but the rider was not hurt, and I repaired my handkerchief as well as I could. However, I would not trust to the strength of it any more in such dangerous enterprises.

I had sent so many petitions for my liberty that his Majesty at length mentioned the matter in a full council, where it was opposed by none except Skyresh Bolgolam, admiral of the realm, who was pleased without any provocation to be my mortal enemy. However, he agreed at length, though he succeeded in himself drawing up the conditions on which I should be set free. After they were read I was requested to swear to perform them in the method prescribed by their laws, which was to hold my right foot in my left hand, and to place the middle finger of my right hand on the crown of my head, and my thumb on the top of my right ear. But I have made a translation of the conditions, which I here offer to the public:

“Golbaste Mamarem Evlame Gurdile Shefin Mully Ully Gue, Most Mighty Emperor of Lilliput, delight and terror of the universe, whose dominions extend to the ends of the globe, monarch of all monarchs, taller than the sons of men, whose feet press down to the center, and whose head strikes against the sun, at whose nod the princes of the earth shake their knees, pleasant as the spring, comfortable as the summer, fruitful as autumn, dreadful as winter: His Most Sublime Majesty proposeth to the Man-Mountain, lately arrived at our celestial dominions, the following articles, which by a solemn oath he shall be obliged to perform:

“First. The Man-Mountain shall not depart from our dominions without our license under the great seal.

“Second. He shall not presume to come into our metropolis without our express order, at which time the inhabitants shall have two hours’ warning to keep within doors.

“Third. The said Man-Mountain shall confine his walks to our principal high roads, and not offer to walk or lie down in a meadow or field of corn.

“Fourth. As he walks the said roads he shall take the utmost care not to trample upon the bodies of any of our loving subjects, their horses or carriages, nor take any of our subjects into his hands without their own consent.

“Fifth. If an express requires extraordinary speed the Man-Mountain shall be obliged to carry in his pocket the messenger and horse a six days’ journey, and return the said messenger (if so required) safe to our imperial presence.

“Sixth. He shall be our ally against our enemies in the island of Blefuscu, and do his utmost to destroy their fleet, which is now preparing to invade us.

“Lastly. Upon his solemn oath to observe all the above articles, the said Man-Mountain shall have a daily allowance of meat and drink sufficient for the support of 1,724 of our subjects, with free access to our royal person, and other marks of our favor. Given at our palace at Belfaburac, the twelfth day of the ninety-first moon of our reign.”

I swore to these articles with great cheerfulness, whereupon my chains were immediately unlocked, and I was at full liberty.

One morning, about a fortnight after I had obtained my freedom, Reldresal, the Emperor’s secretary for private affairs, came to my house, attended only by one servant. He ordered his coach to wait at a distance, and desired that I would give him an hour’s audience. I offered to lie down that he might the more conveniently reach my ear; but he chose rather to let me hold him in my hand during our conversation. He began with compliments on my liberty, but he added that, save for the present state of things at Court, perhaps I might not have obtained it so soon. “For,” he said, “however flourishing we may seem to foreigners, we are in danger of an invasion from the island of Blefuscu, which is the other great empire of the universe, almost as large and as powerful as this of his Majesty. For as to what we have heard you say, that there are other kingdoms in the world, inhabited by human creatures as large as yourself, our philosophers are very doubtful, and rather conjecture that you dropped from the moon, or one of the stars, because a hundred mortals of your size would soon destroy all the fruit and cattle of his Majesty’s dominions. Besides, our histories of six thousand moons make no mention of any other regions than the two mighty empires of Lilliput and Blefuscu, which, as I was going to tell you, are engaged in a most obstinate war, which began in the following manner: It is allowed on all hands that the primitive way of breaking eggs was upon the larger end; but his present Majesty’s grandfather, while he was a boy, going to eat an egg, and breaking it according to the ancient practice, happened to cut one of his fingers. Whereupon the Emperor, his father, made a law commanding all his subjects to break the smaller end of their eggs. The people so highly resented this law that there have been six rebellions raised on that account, wherein one emperor lost his life, and another his crown. It is calculated that eleven hundred persons have at different times suffered death rather than break their eggs at the smaller end. But these rebels, the Bigendians, have found so much encouragement at the Emperor of Blefuscu’s Court, to which they always fled for refuge, that a bloody war, as I said, has been carried on between the two empires for six-and-thirty moons; and now the Blefuscudians have equipped a large fleet, and are preparing to descend upon us. Therefore his Imperial Majesty, placing great confidence in your valor and strength, has commanded me to set the case before you.”

I desired the secretary to present my humble duty to the Emperor, and to let him know that I was ready, at the risk of my life, to defend him against all invaders.

CHAPTER IV

It was not long before I communicated to his Majesty the plan I formed for seizing the enemy’s whole fleet. The Empire of Blefuscu is an island parted from Lilliput only by a channel eight hundred yards wide. I consulted the most experienced seamen on the depth of the channel, and they told me that in the middle, at high water, it was seventy glumguffs (about six feet of European measure). I walked toward the coast, where, lying down behind a hillock, I took out my spy-glass, and viewed the enemy’s fleet at anchor—about fifty men-of-war, and other vessels. I then came back to my house and gave orders for a great quantity of the strongest cables and bars of iron. The cable was about as thick as packthread, and the bars of the length and size of a knitting-needle. I trebled the cable to make it stronger, and for the same reason twisted three of the iron bars together, bending the ends into a hook. Having thus fixed fifty hooks to as many cables, I went back to the coast, and taking off my coat, shoes, and stockings, walked into the sea in my leather jacket about half an hour before high water. I waded with what haste I could, swimming in the middle about thirty yards, till I felt ground, and thus arrived at the fleet in less than half an hour. The enemy was so frightened when they saw me that they leaped out of their ships and swam ashore, where there could not be fewer than thirty thousand. Then, fastening a hook to the hole at the prow of each ship, I tied all the cords together at the end. Meanwhile the enemy discharged several thousand arrows, many of which stuck in my hands and face. My greatest fear was for my eyes, which I should have lost if I had not suddenly thought of the pair of spectacles which had escaped the Emperor’s searchers. These I took out and fastened upon my nose, and thus armed went on with my work in spite of the arrows, many of which struck against the glasses of my spectacles, but without any other effect than slightly disturbing them. Then, taking the knot in my hand, I began to pull; but not a ship would stir, for they were too fast held by their anchors.

Thus the boldest part of my enterprise remained. Letting go the cord, I resolutely cut with my knife the cables that fastened the anchors, receiving more than two hundred shots in my face and hands. Then I took up again the knotted end of the cables to which my hooks were tied, and with great ease drew fifty of the enemy’s largest men-of-war after me.

When the Blefuscudians saw the fleet moving in order, and me pulling at the end, they set up a scream of grief and despair that it is impossible to describe. When I had got out of danger I stopped awhile to pick out the arrows that stuck in my hands and face, and rubbed on some of the same ointment that was given me at my arrival. I then took off my spectacles, and after waiting about an hour, till the tide was a little fallen, I waded on to the royal port of Lilliput.

The Emperor and his whole Court stood on the shore awaiting me. They saw the ships move forward in a large half-moon, but could not discern me, who, in the middle of the channel, was under water up to my neck. The Emperor concluded that I was drowned, and that the enemy’s fleet was approaching in a hostile manner. But he was soon set at ease, for, the channel growing shallower every step I made, I came in a short time within hearing, and holding up the end of the cable by which the fleet was fastened, I cried in a loud voice: “Long live the most puissant Emperor of Lilliput!” The Prince received me at my landing with all possible joy, and made me a Nardal on the spot, which is the highest title of honor among them.

His Majesty desired that I would take some opportunity to bring all the rest of his enemy’s ships into his ports, and seemed to think of nothing less than conquering the whole Empire of Blefuscu, and becoming the sole monarch of the world. But I plainly protested that I would never be the means of bringing a free and brave people into slavery; and though the wisest of the Ministers were of my opinion, my open refusal was so opposed to his Majesty’s ambition that he could never forgive me. And from this time a plot began between himself and those of his Ministers who were my enemies, that nearly ended in my utter destruction.

About three weeks after this exploit there arrived an embassy from Blefuscu, with humble offers of peace, which was soon concluded, on terms very advantageous to our Emperor. There were six ambassadors, with a train of about five hundred persons, all very magnificent. Having been privately told that I had befriended them, they made me a visit, and paying me many compliments on my valor and generosity, invited me to their kingdom in the Emperor their master’s name. I asked them to present my most humble respects to the Emperor their master, whose royal person I resolved to attend before I returned to my own country. Accordingly, the next time I had the honor to see our Emperor I desired his general permission to visit the Blefuscudian monarch. This he granted me, but in a very cold manner, of which I afterward learned the reason.

When I was just preparing to pay my respects to the Emperor of Blefuscu, a distinguished person at Court, to whom I had once done a great service, came to my house very privately at night, and without sending his name desired admission. I put his lordship into my coat pocket, and, giving orders to a trusty servant to admit no one, I fastened the door, placed my visitor on the table, and sat down by it. His lordship’s face was full of trouble; and he asked me to hear him with patience, in a matter that highly concerned my honor and my life.

“You are aware,” he said, “that Skyresh Bolgolam has been your mortal enemy ever since your arrival, and his hatred is increased since your great success against Blefuscu, by which his glory as admiral is obscured. This lord and others have accused you of treason, and several councils have been called in the most private manner on your account. Out of gratitude for your favors I procured information of the whole proceedings, venturing my head for your service, and this was the charge against you:

“First, that you, having brought the imperial fleet of Blefuscu into the royal port, were commanded by his Majesty to seize all the other ships, and put to death all the Bigendian exiles, and also all the people of the empire who would not immediately consent to break their eggs at the smaller end. And that, like a false traitor to his Most Serene Majesty, you excused yourself from the service on pretence of unwillingness to force the consciences and destroy the liberties and lives of an innocent people.

“Again, when ambassadors arrived from the Court of Blefuscu, like a false traitor, you aided and entertained them, though you knew them to be servants of a prince lately in open war against his Imperial Majesty.

“Moreover, you are now preparing, contrary to the duty of a faithful subject, to voyage to the Court of Blefuscu.

“In the debate on this charge,” my friend continued, “his Majesty often urged the services you had done him, while the admiral and treasurer insisted that you should be put to a shameful death. But Reldresal, secretary for private affairs, who has always proved himself your friend, suggested that if his Majesty would please to spare your life and only give orders to put out both your eyes, justice might in some measure be satisfied. At this Bolgolam rose up in fury, wondering how the secretary dared desire to preserve the life of a traitor; and the treasurer, pointing out the expense of keeping you, also urged your death. But his Majesty was graciously pleased to say that since the council thought the loss of your eyes too easy a punishment, some other might afterward be inflicted. And the secretary, humbly desiring to be heard again, said that as to expense your allowance might be gradually lessened, so that, for want of sufficient food you should grow weak and faint, and die in a few months, when his Majesty’s subjects might cut your flesh from your bones and bury it, leaving the skeleton for the admiration of posterity.

“Thus, through the great friendship of the secretary the affair was arranged. It was commanded that the plan of starving you by degrees should be kept a secret; but the sentence of putting out your eyes was entered on the books. In three days your friend the secretary will come to your house and read the accusation before you, and point out the great mercy of his Majesty, that only condemns you to the loss of your eyes—which, he does not doubt, you will submit to humbly and gratefully. Twenty of his Majesty’s surgeons will attend, to see the operation well performed, by discharging very sharp-pointed arrows into the balls of your eyes as you lie on the ground.

“I leave you,” said my friend, “to consider what measures you will take; and, to escape suspicion, I must immediately return, as secretly as I came.”

His lordship did so; and I remained alone, in great perplexity. At first I was bent on resistance; for while I had liberty I could easily with stones pelt the metropolis to pieces; but I soon rejected that idea with horror, remembering the oath I had made to the Emperor, and the favors I had received from him. At last, having his Majesty’s leave to pay my respects to the Emperor of Blefuscu, I resolved to take this opportunity. Before the three days had passed I wrote a letter to my friend the secretary telling him of my resolution; and, without waiting for an answer, went to the coast, and entering the channel, between wading and swimming reached the port of Blefuscu, where the people, who had long expected me, led me to the capital.

His Majesty, with the royal family and great officers of the Court, came out to receive me, and they entertained me in a manner suited to the generosity of so great a prince. I did not, however, mention my disgrace with the Emperor of Lilliput, since I did not suppose that prince would disclose the secret while I was out of his power. But in this, it soon appeared, I was deceived.

CHAPTER V

Three days after my arrival, walking out of curiosity to the northeast coast of the island, I observed at some distance in the sea something that looked like a boat overturned. I pulled off my shoes and stockings, and wading two or three hundred yards, I plainly saw it to be a real boat, which I supposed might by some tempest have been driven from a ship. I returned immediately to the city for help, and after a huge amount of labor I managed to get my boat to the royal port of Blefuscu, where a great crowd of people appeared, full of wonder at sight of so prodigious a vessel. I told the Emperor that my good fortune had thrown this boat in my way to carry me to some place whence I might return to my native country, and begged his orders for materials to fit it up, and leave to depart—which, after many kindly speeches, he was pleased to grant.

Meanwhile the Emperor of Lilliput, uneasy at my long absence (but never imagining that I had the least notice of his designs), sent a person of rank to inform the Emperor of Blefuscu of my disgrace; this messenger had orders to represent the great mercy of his master, who was content to punish me with the loss of my eyes, and who expected that his brother of Blefuscu would have me sent back to Lilliput, bound hand and foot, to be punished as a traitor. The Emperor of Blefuscu answered with many civil excuses. He said that as for sending me bound, his brother knew it was impossible. Moreover, though I had taken away his fleet he was grateful to me for many good offices I had done him in making the peace. But that both their Majesties would soon be made easy; for I had found a prodigious vessel on the shore, able to carry me on the sea, which he had given orders to fit up; and he hoped in a few weeks both empires would be free from me.

With this answer the messenger returned to Lilliput; and I (though the monarch of Blefuscu secretly offered me his gracious protection if I would continue in his service) hastened my departure, resolving never more to put confidence in princes.

In about a month I was ready to take leave. The Emperor of Blefuscu, with the Empress and the royal family, came out of the palace; and I lay down on my face to kiss their hands, which they graciously gave me. His Majesty presented me with fifty purses of sprugs (their greatest gold coin) and his picture at full length, which I put immediately into one of my gloves, to keep it from being hurt. Many other ceremonies took place at my departure.

I stored the boat with meat and drink, and took six cows and two bulls alive, with as many ewes and rams, intending to carry them into my own country; and to feed them on board, I had a good bundle of hay and a bag of corn. I would gladly have taken a dozen of the natives; but this was a thing the Emperor would by no means permit, and besides a diligent search into my pockets, his Majesty pledged my honor not to carry away any of his subjects, though with their own consent and desire.

Having thus prepared all things as well as I was able, I set sail. When I had made twenty-four leagues, by my reckoning, from the island of Blefuscu, I saw a sail steering to the northeast. I hailed her, but could get no answer; yet I found I gained upon her, for the wind slackened; and in half an hour she spied me, and discharged a gun. I came up with her between five and six in the evening, Sept. 26, 1701; but my heart leaped within me to see her English colors. I put my cows and sheep into my coat pockets, and got on board with all my little cargo. The captain received me with kindness, and asked me to tell him what place I came from last; but at my answer he thought I was raving. However, I took my black cattle and sheep out of my pocket, which, after great astonishment, clearly convinced him.

We arrived in England on the 13th of April, 1702. I stayed two months with my wife and family; but my eager desire to see foreign countries would suffer me to remain no longer. However, while in England I made great profit by showing my cattle to persons of quality and others; and before I began my second voyage I sold them for 600l. I left 1500l. with my wife, and fixed her in a good house; then taking leave of her and my boy and girl, with tears on both sides, I sailed on board the “Adventure.” .

Swift

Un viaggio a Lilliput

CAPITOLO I

Mio padre aveva una piccola tenuta nel Nottinghamshire e io ero il terzo di quattro figli. Mi mandò a Cambridge a quattordici anni e dopo aver studiato lì per tre anni fui collocato come apprendista da Mr. Bates, un famoso chirurgo di Londra. Lì, siccome mio padre ogni tanto mi mandava piccole somme di denaro, le spesi per imparare la navigazione e altre arti utili a chi voglia viaggiare, come ho sempre creduto la mia sorte mi avrebbe fatto fare una volta o l’altra.

Tre anni dopo averlo lasciato il mio buon maestro, Mr. Bates, mi raccomandò come chirurgo di bordo sulla “Rondine” sulla quale viaggia per tre anni. Quando tornai indietro, mi stabilii a Londra e, avendo affittato una parte di una piccola casa, sposai Miss Mary Burton, figlia di Mr. Edmund Burton, calzettaio.

Ma il mio buon maestro Mr. Bates morì due anni dopo, e siccome avevo pochi amici, i miei affari cominciarono ad andar male e decisi di prendere ancora il mare. Dopo diversi viaggi, accettai un’offerta dal Capitano W. Pritchard, padrone dell’ “Antilope”, che stava per fare un viaggio nel Mare del Sud. Salpammo da Bristol il 4 maggio 1699 e il nostro viaggio all’inizio fu molto favorevole.

Ma al passaggio delle Indie Orientali fummo condotti da una violenta tempesta a nord-ovest della Terra di Van Diemen. Dodici membri del nostro equipaggio morirono per il lavoro duro e il pessimo cibo, e il resto versava in condizioni di estrema debolezza. Il 5 novembre, essendo il tempo assai nebbioso, i marinai avvistarono una roccia non oltre 120 iarde dalla nave; ma il vento era così forte che fummo condotti proprio verso di essa e immediatamente la nave si spaccò. Sei membri dell’equipaggio, tra i quali io, calando una scialuppa, si allontanarono dalla nave e remammo per tre leghe finché non ne potemmo più. Perciò ci affidammo alla clemenza delle onde e in circa mezz’ora la scialuppa fu capovolta da una raffica improvvisa. Che cosa ne fu dei miei compagni nella scialuppa o di quelli che sfuggirono alla roccia o furono lasciati sul vascello, non posso dirlo, ma posso concludere che furono tutti perduti. Da parte mia, nuotai dove mi dirigeva la fortuna e fui sospinto avanti dal vento e dalla marea, ma quando non fui più in grado di lottare, mi ritrovai a toccare il fondo. Nel frattempo la tempesta era molto diminuita. Alla fine raggiunsi la spiaggia, intorno alle otto di sera, e avanzai circa mezzo miglio sulla terraferma, ma non potevo scorgere segni di abitanti. Ero estremamente stanco e con il calore delle condizioni atmosferiche mi ritrovai molto incline a dormire. Mi sdraiai sull’erba, che era molto corta e soffice, e dormii per circa nove ore più profondamente di quanto avessi mai fatto in vita mia. Quando mi sveglia, si stava facendo giorno. Tentai di sollevarmi, ma non potei perché siccome mi era accaduto di sdraiarmi sul dorso, mi ritrovai le braccia e le gambe legate al terreno da ciascun lato e i miei capelli, che erano lunghi e folti, legati al suolo nella medesima maniera. Potevo solo guardare verso l’alto. Il sole cominciava a scottare e la luce mi feriva gli occhi. Udii un rumore confuso intorno a me, ma non potevo vedere nulla tranne il cielo. In poco tempo sentii qualcosa di vivo che si muoveva sulla mia gamba sinistra e, avanzando delicatamente verso il mio petto, giunse quasi al mio mento quando, abbassando lo sguardo, mi accorsi che fosse una creatura umana, non più alta di sei pollici, con un arco e una freccia in mano e una faretra sul dorso.

Nel frattempo ne sentii almeno altri quaranta che seguivano il primo. Ero sommamente sbalordito e urlai così sonoramente che corsero via tutti terrorizzati; alcuni di loro rimasero feriti per le cadute che fecero saltando dal mio fianco sul terreno. In ogni modo tornarono ben presto e uno di loro, avvicinandosi tanto da vedere tutto il mio viso, sollevò le mani ammirato. In tutto ciò io giacevo in grande ansia ma alla fine, divincolandomi per liberarmi, riuscii a rompere le corde che mi legavano al suolo il braccio sinistro e nel medesimo tempo, con un violento colpo che mi fece molto male, allentai un pochino anche le corde che mi legavano i capelli, così che potessi girare la testa di due pollici. Le creature corsero via una seconda volta prima che io potessi afferrarle, poi ci fu un grande urlo e in un attimo sentii un centinaio di frecce scagliate sulla mia mano sinistra, che mi punsero come tanti aghi. Per giunta ne lanciarono altre in aria, molte delle quali mi caddero sul viso, che coprii immediatamente con la mano sinistra. Quando la pioggia di frecce fu cessata, io gemetti di angoscia e di dolore e allora, divincolandomi ancora per liberarmi, mi scaricarono un altra selva di frecce più vasta della prima e alcuni di loro tentarono di di pungermi con le lance; per fortuna avevo una giacca di pelle che non poterono perforare. Stavolta ritenni più prudente restare immobile fino alla notte quando, la mia gamba sinistra cominciando ad essere libera, avrei potuto facilmente svincolarmi; in quanto agli abitanti, pensai che avrei potuto lottare con il più grande esercito che avrebbero potuto mandarmi contro se fossero stati tutti delle dimensioni di quello che avevo visto. Quando la gente notò che stavo tranquillo, non scagliò più frecce, ma dal rumore intuii che il loro numero era cresciuto; a circa quattro iarde da me, per più di un’ora, vi fu un battere come di gente al lavoro. Poi voltando la testa quel tanto che mi permettevano i pioli e le corde, vidi un palco innalzato, a circa un pie de e mezzo dal terreno, con due o tre scale per salirvi. Dal palco, uno di loro, che sembrava essere una persona di rango, mi rivolse un lungo discorso del quale non potei capire una parola, sebbene potessi dire dalle sue maniere che talvolta mi minacciava e altre volte mi parlava con misericordia e gentilezza. Risposi poche parole nella maniera più sottomessa e essendo alquanto stremato dalla fame, non potei fare a meno di mostrare la mia impazienza portandomi di frequente la mano alla bocca a significare che volevo cibo. Egli mi comprese benissimo e, scendendo dal palco, ordinò che alcune scale fossero messe al mio fianco e sulle quali salirono un centinaio di abitanti e camminarono verso la mia bocca con canestri pieni di cibo che era stato portato per ordine del re quando aveva ricevuto per primo mie notizie. C’erano cosce e spalle come di montone, ma più piccole delle ali di allodola. Ne mangiai due o tre in un boccone e presi tre pagnotte alla volta. Mi servirono più in fretta che poterono, con molti segni di meraviglia per il mio appetito. Poi feci segno che volevo qualcosa da bere. Intuirono che una piccola quantità non sarebbe stata sufficiente ed essendo un popolo ingegnoso, sollevarono una delle loro botti più grandi, la rotolarono verso la mia mano e tolsero il tappo. La bevvi in un sorso, cosa che feci agevolmente, perché non conteneva più di mezza pinta. Mi portarono una seconda botte, che bevvi, e feci segno per averne ancora; ma non ne avevano più da darmi. In ogni modo non mi meravigliai abbastanza dell’ardire di quelle piccole creature mortali che osavamo montare su di me e camminare sul mio corpo, mentre una delle mie mani era libera, senza tremare alla vista di una creatura così grande quale io dovevo sembrare loro. Dopo un po’ di tempo comparve di fronte a me una persona di alto rango inviata da su Maestà Imperiale. Sua eccellenza, essendomi salito sulla gamba sinistra, avanzò verso il mio viso con almeno una dozzina di persone al seguito e parlò per circa dieci minuti, spesso indicando avanti, cosa che poi scoprì dopo, verso la capitale a circa mezzo miglio di distanza, dove era stato ordinato da Sua Maestà che fossi condotto. Feci segno con la mano libera, indicando l’altra ( ma sopra la testa di Sua Eccellenza per timore di urtare lui o il suo seguito) per mostrare che desideravo essere liberato. Sembrò capirmi abbastanza bene perché scosse la testa sebbene facesse altri segni per farmi comprendere che avrei mangiato e bevuto abbastanza e avrei avuto un buon trattamento. Allora ebbi ancora una volta la tentazione di scappare, ma quando sentii il bruciore delle loro frecce sul viso e sulle mani, che erano tutte una vescica e notai oltretutto che il numero dei mie nemici aumentava, feci in modo di far capire loro che avrebbero potuto fare di me ciò che volevano. Allora mi medicarono il viso e le mani con un unguento lenitivo che in pochi minuti eliminò il bruciore delle frecce. Il sollievo dal dolore e dalla fame mi rese sonnolento e in breve mi addormentai. Dormii per circa otto ore, come mi fu detto dopo, e non mi meravigliai perché i medici, per ordine dell’Imperatore, avevano mescolato un sonnifero nella botte di vino.

Sembra che, quando fui scoperto addormentato sul terreno dopo il naufragio, l’Imperatore ne avesse ricevuto subito notizia e avesse deciso che io dovessi essere legato nella maniera che vi ho riferito (cosa che fu fatta di notte, mentre dormivo), che mi fosse data abbondanza di cibo e di bevande e fece preparare una macchina per portarmi nella capitale. Cinquecento carpentieri e ingegneri furono messi subito al lavoro per preparare il macchinario. Era un’armatura di legno, sollevata tre pollici dal suolo, lunga circa sette piedi e larga quattro, che si muoveva su ventidue ruote. Ma la cosa difficile era piazzarmici. Allo scopo furono eretti ottanta pali e corde molto forti furono assicurate ai bendaggi avvolti attorno al mio collo, alle mani, al corpo e alle gambe. Novecento degli uomini più forti furono impiegati per tirare queste corde tramite carrucole legate ai pali e in meno di tre ore io fui sollevato e deposto sul macchinario e poi legato saldamente. Millecinquecento dei più robusti cavalli dell’Imperatore, ognuno alto quattro pollici e mezzo, furono impiegati per trascinarvi verso la capitale. Ma mentre veniva fatto tutto ciò, io giacevo profondamente addormentato e non mi svegliai se non quattro ore dopo l’inizio del nostro viaggio.

L’Imperatore e tutta la sua corte vennero a incontrami quando raggiungemmo la capitale, ma i suoi grandi ufficiali non permisero che Sua Maestà mettesse a repentaglio la propria persona salendo sul mio corpo. Quando il carro si fermò dove sorgeva un antico tempio, supposi di essere nel posto più grande dell’intero regno e lì era stato deciso che avrei alloggiato. Vicino al grande cancello, attraverso il quale io avrei potuto facilmente strisciare, erano fissate novantuno catene, come quelle a cui tengono appesi gli orologi le dame, che erano assicurate alla mia gamba sinistra con trentasei lucchetti e quando gli operai constatarono che mi sarebbe stato impossibile spezzarli, tagliarono tutte le corde che mi trattenevano. Allora mi alzai, sentendomi malinconico come mai ero stato in vita mia. Ma il rumore e lo stupore della gente nel vedermi sollevare e camminare fu inesprimibile. Le catene che mi trattenevano le gambe erano lunghe circa due iarde e mi concedevano la libertà di camminare solo sono avanti e indietro in semicerchio, ma di sgusciare dentro e sdraiarmi lungo disteso all’interno del tempio. L’Imperatore avanzò verso di me tra i suoi cortigiani, tutti magnificamente vestiti, mi osservò con grande ammirazione ma si tenne a distanza dalla mia catena. Era più alto circa la larghezza della mia unghia di qualsiasi altro cortigiano, da solo era sufficiente a incutere soggezione in chi lo guardava, ed era aggraziato e maestoso.

Per vederlo meglio, mi sdraiai su un fianco così che il mio viso fosse a livello del suo e lui rimase in piedi a tre iarde. In ogni modo successivamente lo ebbi per molto tempo in mano e perciò non posso ingannarmi. Il suo abito era molto semplice, ma calzava un elmetto un lucente elmetto d’oro, adorno di gioielli e di piume. Impugnava la spada per difendersi se mi fossi liberato; era alto almeno tre pollici e l’elsa era d’oro, tempestata di diamanti. La sua voce era acuta, ma molto chiara. Sua Maestà Imperiale mi parlò spesso e io risposi; ma nessuno dei due poteva intendere una parola.

CAPITOLO II

Dopo circa due ore la corte si ritirò e fui lasciato con una robusta guardia a tenere a bada la folla, molta della quale ebbe l'impudenza di scagliarmi frecce mentre sedevo presso la porta della mia casa. Ma il colonnello ordinò che sei di loro fossero catturati e consegnati legati nelle mie mani. Io ne misi cinque nel taschino della giacca e quanto al sesto, fgli feci una smorfia come se volessi mangiarlo vivo. Il pover’uomo gridava terribilmente e il colonnello e i suoi ufficiali furono molto angosciati, specialmente quando mi videro tirare fuori un temperino. Ma ben presto li rinfrancai perché, tagliando le corde con cui era legato, lo deposi gentilmente a terra e lui corse via. Trattai nel medesimo modo gli altri, estraendoli a uno a una dal taschino, e vidi che sia i soldati sia la folla furono contenti di questa prova della mia gentilezza.

Facendosi notte, entrai in casa con qualche difficoltà e lì giacqui sul terreno, come dovetti continuare a fare per due settimane, finché mi fu preparato un letto con seicento letti di misura regolare.

Mi furono forniti seicento servitori e trecento sarti mi prepararono un completo di abiti. Inoltre dei dei migliori insegnanti di Sua Maestà furono impegnati per insegnarmi la loro lingua così che presto fui in grado di conversare alla meglio con l'Imperatore, che spesso mi onorava di una sua visita. Le prime parole che seppi pronunciare espressero il desiderio che si compiacesse di restituirmi la libertà, cosa che ripetei in ginocchio ogni giorno, ma lui rispose che ciò sarebbe avvenuto a tempo debito e che prima dovevo giurare di restare in pace con lui e con il suo regno. Mi disse anche che, secondo le leggi della nazione, io dovevo essere perquisito da due dei suoi ufficiali e che siccome ciò non poté essere fatto senza il mio aiuto, li affidava alle mie mani e qualsiasi cosa avessero preso, mi sarebbe stata restituita quando avessi lasciato il paese. Sollevai i due ufficiali e li misi nel taschino della giacca. Questi signori, che avevano con sé penna, inchiostro e carta, fecero una lista precisa di tutto ciò che videro, lista che poi io tradussi in inglese e che recita così:

"Nella tasca destra del grande Uomo Montagna abbiamo trovato solo un grosso pezzo di stoffa ruvida, larga abbastanza da coprire il tappeto nella principale sala di rappresentanza di Vostra Maestà. Nella tasca sinistra abbiamo visto un enorme baule d'argento, con il coperchio d'argento, che non siamo riusciti a sollevare. Chiedemmo che fosse aperto e uno di noi , entrandovi, si trovò immerso a metà gamba in una specie di polvere, un po' della quale, volandoci sul viso, ci ha fatto fare una serie di starnuti. Nella tasca destra del panciotto trovammo un certo numero di piccole cose bianche, ripiegate l'una sull'altra, della misura di circa tre uomini, legate da una robusta corda e disegnate con figure nere che umilmente ritenemmo fossero scritture. Nella tasca sinistra c'era una specie di attrezzo dal cui dorso si dipartivano venti lunghi peli, dalla qual cosa noi congetturiamo che l'Uomo Montagna si pettini la testa. Nella tasca più piccola sul lato destro c'erano diversi pezzi rotondi e piatti di metallo bianco e rosso, di diverse misure. Alcuni di quelli bianchi, che sembravano d'argento, erano così larghi e pesanti che il mio compagno ed io a malapena li potemmo sollevare. Da un'altra tasca pendeva una enorme catena d'argento con legato un meraviglioso tipo di manufatto, un globo metà d'argento e metà di un qualche metallo trasparente; dal lato trasparente vedemmo certe strane figure e sebbene volessimo toccarle, le nostre dita furono fermate da quella sostanza lucente. Il manufatto emetteva un incessante rumore, come di un mulino ad acqua, e noi ipotizzammo che fosse un qualche animale sconosciuto o il dio che lui venera, ma probabilmente la seconda ipotesi perché lui ci disse che raramente faceva qualcosa senza consultarlo. Questa è la lista di ciò che abbiamo trovato sul corpo dell'Uomo Montagna, il quale ci ha trattati con grande urbanità."

Avevo una tasca nascosta sfuggita alla loro perquisizione, che conteneva un paio di occhiali e un piccolo cannocchiale i quali, senza conseguenze per l'Imperatore, pensai sul mio onore non fossi obbligato a rivelare.

CAPITOLO III

La docilità e il buon comportamento mi avevano guadagnato finora il favore dell'Imperatore e della sua corte, e del popolo in generale, così che comincia a sperare di ottenere la libertà in breve tempo. I nativi pian piano cominciarono ad aver meno paura di danni da parte mia. A volte mi sdraiavo e lasciavo che cinque o sei di loro danzassero sulla mia mano; e alla fine i bambini e le bambine osarono avvicinarsi e giocare a nascondino tra i miei capelli.

I cavalli dell'esercito e delle scuderie reali non furono più impauriti, venendo addestrati quotidianamente davanti a me; uno dei cacciatori dell'Imperatore, in sella a un grande destriero, saltò il mio piede con la scarpa e tutto, il che fu un balzo davvero prodigioso.

Un giorno divertii l'Imperatore in un modo veramente insolito. Presi nove bastoncini e li infilai saldamente nel terreno di una piazza. Poi presi altri quattro bastoncini e li legai paralleli a ciascun angolo, a circa due piedi dal terreno. Legai il mio fazzoletto ai nove bastoncini eretti e lo stesi da tutti i lati finché fu teso come la pelle di un tamburo; poi volli che l'Imperatore mandasse una scelta delle sue bestie migliori, in numero di ventiquattro, a esercitarsi su quella spianata. Sua Maestà approvò la proposta e io li presi a uno a uno, ciascuno con il proprio ufficiale con il quale esercitarsi. Appena furono in ordine, si divisero in due schiere, lanciarono frecce spuntate, impugnarono le spade, avanzarono e s'inseguirono, in breve fecero sfoggio della miglior disciplina militare che avessi mai veduto. I bastoncini paralleli li tenevano al sicuro loro e i cavalli dal cadere dal piano e l'Imperatore era così contento che ordinò che l'intrattenimento fosse ripetuto per diversi giorni e lo convinse a a farsi sollevare da me nella sua poltrona all’altezza di due iarde dal piano affinché potesse vedere tutta l'esibizione. Fortunatamente non accadde nessun incidente, solo un cavallo selvaggio, sbattendo gli zoccoli, fece un buco nel mio fazzoletto e rovesciò se stesso e il proprio cavaliere. Immediatamente sollevai entrambi e, coprendo il buco con una mano, con l'altra deposi a terra la truppa così come l'avevo fatta salire. Il cavallo che era caduto si era fatto uno strappo alla spalla, ma il cavaliere non era ferito e io riparai il fazzoletto meglio che potei. In ogni modo non mi fidai più della sua robustezza per qualsiasi altra impresa così rischiosa.

Avevo inoltrato così tante suppliche per la mia liberazione che Sua Maestà alla fine parlò dell'argomento durante il consiglio in cui nessuno si oppose, a parte Skyresh Bolgolam, ammiraglio del regno, che si compiaceva, senza alcuna provocazione da parte mia, di essere mio mortale nemico. In ogni modo alla fine acconsentì, sebbene impose lui stesso le condizioni secondo le quali sarei stato libero. Dopo che mi furono lette, mi fu richiesto di giurare di rispettarle nei modi prescritti dalla legge, cosa che feci prendendomi il piede destro con la mano sinistra, mettendo il dito medio della mano destra sul cocuzzolo della testa e il pollice in cima al mio orecchio destro. Ho fatto una traduzione delle condizioni e la offro qui al pubblico:

"Golbaste Mamarem Evlame Gurdile Shefin Mully Ully Gue, Potentissimo Imperatore di Lilliput, delizia e terrore dell'universo, i cui domini si estendono ai confini del globo, monarca di tutti i monarchi, il più alto tra i figli degli uomini, i cui piedi posano sul centro e la cui testa urta contro il sole, al cui cenno i principi della terra piegano le ginocchia, piacevole come la primavera, confortevole come l'estate, fruttifero come l'autunno, spaventoso come l'inverno: Sua Sublime Maestà propone all'Uomo Montagna, recentemente giunto ni nostri celestiali possedimenti, i seguenti articoli che con solenne giuramento sarà obbligato a rispettare:

"Primo. L'Uomo Montagna non si allontanerà dai nostri domini senza il nostro permesso munito di gran sigillo.

"Secondo. Non oserà entrare nelle nostre metropoli senza espresso ordine; in tal caso gli abitanti dovranno essere avvisati con due di anticipo perché non esvcano di casa.

"Terzo. Il cosiddetto Uomo Montagna limiterà le sue passeggiate alle strade principali e non si permetterà di camminare o sdraiarsi nei prati o nei campi di mais.

"Quarto. Quando cammina sulle suddette strade dovrà avere la più grande cura di non calpestare i corpi di nessuno dei nostri amati sudditi, dei loro cavalli o carri, né di prendere in mano nessuno dei nostri sudditi senza il suo consenso.

"Quinto. Se un messaggio richiederà una consegna urgente, l'Uomo Montagna sarà obbligato a portare in tasca il messaggero e il cavallo per un viaggio della durata di sei giorni e a restituire sano e salvo il suddetto messaggero (se così richiesto) alla nostra imperiale presenza .

"Sesto. Sarà nostro alleato contro i nostri nemici dell'isola di Blefuscu e farà del proprio meglio per distruggere la loro flotta che adesso si sta preparando a invaderci.

"In ultimo. Dietro solenne giuramento di osservare tutti questi articoli, il cosiddetto Uomo Montagna avrà sostentamento giornaliero di cibo e bevande pari al sostentamento di 1724 sudditi, con libero accesso alla nostra regale persona e con altri segni del nostro favore. Redatto nel nostro palazzo a Belfaburac, il ventesimo giorno della novantunesima luna del nostro regno."

Giurai su questi articoli con grande gioia, dopodiché le mie catene furono immediatamente sciolte e fui totalmente libero.

Una mattina, due settimane dopo aver ottenuto la libertà, Reldresa, il segretario dell'Imperatore per gli affari privati, venne a casa mia scortato da un solo servitore. Ordinò alla carrozza di aspettare a una certa distanza e volle che gli concedessi un'ora di udienza. Mi offrii di sdraiarmi affinché potesse raggiungere meglio il mio orecchio, ma lui invece preferì che lo tenessi in mano durante la nostra conversazione. Cominciò congratulandosi per la mia liberazione, ma aggiunse che, se non fosse stato per l'attuale stato delle cose a Corte, forse non l'avrei ottenuta così presto. Disse: "Perché per quanto a un forestiero la nostra situazione possa apparire florida, noi siamo a rischio di invasione da parte dell'isola di Blefuscu, che è l'altro grande impero dell'universo, quasi grande e potente quanto quello di Sua Maestà. Perché di quanto vi abbiamo sentito dire, che ci siano altri regni nel mondo, abitati da creature umane grandi come voi, i nostri filosofi dubitano molto e ipotizzano che voi siate caduto dalla luna o dalle stelle, perché un centinaio di mortali della vostra taglia ben presto distruggerebbero tutti i prodotti e le mandrie dei domini di Sua Maestà. Inoltre le nostre cronache, vecchie di seimila lune, non fanno menzione di nessun'altra regione che quelle dei due potenti imperi di Lilliput e di Blefuscu i quali, come stavo per dirvi, hanno ingaggiato una guerra molto ostinata che è cominciata nel seguente modo: è ammesso da tutti che il modo iniziale di sorbire le uova sia dall'estremità più larga; ma avvenne che il nonno dell'attuale Maestà, quando era un bambino, dovendo sorbire un uovo e avendolo rotto secondo l'antica pratica, si tagliò un dito. A questo punto l'Imperatore suo padre emanò una legge che ordinava a tutti i sudditi di rompere le uova dall'estremità più piccola. Il popolo si risentì enormemente per questa legge, tanto che vi furono sei ribellioni scopiate per questa ragione e nelle quali un Imperatore perse la vita e un altro la corona. È stato calcolato che undicimila persone in tempi diversi abbiano affrontato la morte piuttosto che rompere le loro uova dalla parte più piccola. Ma questi ribelli, i Bigenian, hanno trovato un tale sostegno da parte della Corte dell'Imperatore di Blefuscu, presso la quale spesso sono fuggiti a rifugiarsi, che una guerra sanguinosa, come ho detto, è stata condotta dai due imperi per trentasei lune; ora i Blefuscudiani hanno armato una vasta flotta e si stanno preparando a calare su di noi. Per questo Sua Maestà Imperiale, confidando sommamente nel vostro valore nella vostra forza, mi ha ordinato di sottoporvi il caso."

Chiesi al segretario che presentasse all'Imperatore i miei umili omaggi e gli lasciai intendere di essere pronto a difenderlo contro tutti gli invasori, a rischio della mia stessa vita.

CAPITOLO IV

Non ci volle molto perché comunicassi a Sua Maestà il piano che avevo concepito per catturare l'intera flotta nemica. L'impero di Blefuscu è un'isola separata da Lilliput solo da un canale largo ottocento iarde. Consultai gli uomini mare più esperti circa la profondità del canale e mi dissero che nel mezzo, dove l'acqua era alta, ela profondo settanta glumguff (circa sei piedi secondo la misurazione europea). Camminai verso la costa dove, sdraiandomi dietro una piccola collina, presi il mio cannocchiale e osservai la flotta nemica all'ancora, circa cinquanta navi da guerra e altri vascelli. Poi tornai a casa e diedi ordine che fossero fabbricate una gran quantità dei più robusti cavi e sbarre di ferro. I cavi erano spessi quanto uno spago e le sbarre della lunghezza e della misura di un ferro da calza. Unii a tre a tre i cavi per renderli più forti e per la medesima ragione unii tre sbarre di ferro, piegandone a uncino le estremità. Avendo così fissato cinquanta uncini a ogni cavo, tornai sulla costa e, togliendo il soprabito, le scarpe e le calze, camminai nell'acqua con la mia giacca di pelle circa un'ora e mezza prima dell'alta marea. Guadai il canale più in fretta che potei, nuotando nel mezzo per circa trenta iarde, finché toccai terra e giunsi alla flotta in meno di mezz'ora. I nemici ebbero tanta paura quando mi videro che saltarono in acqua dalle navi e nuotarono verso la riva, dove non potevano esserci meno di trentamila anime. Poi assicurando un uncino alla prua di ciascuna nave, legai tutti cavi insieme in un unica fune. Nel frattempo i nemici mi scagliarono contro varie migliaia di frecce, molte delle quali mi colpirono le mani e il viso. Il mio timore più grande era per gli occhi, che avrei potuto perdere se non avessi pensato immediatamente al mio paio di occhiali che era sfuggito all'ispezione dell'Imperatore. Lo tirai fuori e me lo posi sul naso e così munito proseguii il mio lavoro, a dispetto delle frecce, molte delle quali furono lanciate contro il vetro dei miei occhiali, ma senza nessun effetto se non quello di sconquassarmeli un pochino. Poi, tenendo il fascio di cavi in mano, cominciai a tirare; non una nave si mosse perché erano ancorate saldamente.

Restava da compiere la parte più ardimentosa della mia impresa. Lasciando andare il fascio di funi, tagliai risolutamente con il coltello i cavi che trattenevano le ancore, ricevendo più di duecento colpi sul viso e sulle mani. Poi ripresi il fascio di funi legate insieme alle quali erano assicurati gli uncini e con grande facilità mi tirai dietro cinquanta delle più grandi navi da guerra nemiche.

Quando i Blefuscudiani videro la flotta che si muoveva in ordine e me che la trascinavo per l'estremità, lanciarono un grido di dolore e di disperazione che è impossibile descrivere. Quando fui fuori pericolo, mi fermai un attimo a levare le frecce che erano infilate nelle mani e sul viso e mi strofinai con un po' dell'unguento che mi avevano dato al mio arrivo. Poi mi tolsi gli occhiali e, dopo aver atteso circa un'ora finché la marea fu un po' calata, mi feci strada faticosamente fino al porto reale di Lilliput.

L'Imperatore e l'intera Corte erano sulla spiaggia ad aspettarmi. Videro le navi avanzare in un'ampia mezzaluna, ma non riuscivano a vedere me che, in mezzo al canale, ero immerso nell'acqua fino al collo. L'Imperatore concluse che fossi annegato e che la flotta nemica si stesse avvicinando con intendimento ostile. Ma ben presto i suoi timori svanirono perché, diventando il canale sempre meno profondo a ogni passo che facevo, giunsi in poco tempo alla portata del suo orecchio e, sollevando l'estremità del fascio di funi con cui era legata la flotta, gridai con voce sonora: "Lunga vita al più potente Imperatore di Lilliput!" Il principe mi ricevette allo sbarco con la più grande gioia e mi creò immediatamente Nardal, che è il più alto titolo onorifico tra di loro.

Sua Maestà volle che in qualche altro modo portassi tutto il resto della flotta nemica nei suoi porti e sembrò che pensasse a nulla di meno che conquistare l'intero impero di Blefuscu e diventare il solo monarca del mondo. Ma i protestai civilmente che non mi sarei mai adoperato per ridurre in schiavitù un popolo libero e valoroso; sebbene il più saggio dei Ministri fosse della mia opinione, il mio aperto rifiuto fu così contrario alle ambizioni di Sua Maestà che non poté perdonarmi. Da quel momento cominciò il complotto tra lui e quei Ministri che erano miei nemici, e che mi portò vicino alla mia totale distruzione.

Circa tre settimane dopo la mia impresa, giunse un'ambasciata da Blefuscu, con umili profferte per una pace che fu subito conclusa, in termini molto vantaggiosi per il nostro Imperatore. Erano sei ambasciatori con un corteo di circa cinquecento persone, tutte magnifiche. Essendo stati privatamente informati del mio comportamento amichevole nei loro confronti, vennero a farmi visita e mi fecero molti complimenti per il mio valore e per la mia generosità, invitandomi nel loro regno in nome dell'Imperatore loro signore. Chiesi loro di presentare i miei più umili rispetti all'Imperatore loro signore, alla cui regale persona intendevo presentarmi prima di tornare nel mio paese. Di conseguenza, la volta successiva in cui ebbi l'onor di vedere il nostro Imperatore, chiesi il suo permesso ufficiale per visitare il monarca Blefuscuriano. Me lo concesse, ma in modo molto freddo, del quale più tardi seppi la ragione.

Quando mi stavo giusto preparando a porgere i miei rispetti all'Imperatore di Blefuscu, una distinta personalità di Corte, alla quale una volta avevo reso un gran servigio, venne a casa mia di notte in forma privata e, senza rivelare il proprio nome, chiese di essere ricevuto. Misi sua signoria nel taschino del mio soprabito e, dando ordine a un fedele servitore di non far entrare nessun altro, chiusi a chiave la porta, misi il mio visitatore sul tavolo e sedetti lì. Il volto di sua signoria era segnato dalla preoccupazione e mi chiese di ascoltarlo con pazienza riguardo un argomento che aveva che fare con il mio onore e con la mia vita.

Disse: "Sapete che Skyresh Bolgolam è stato vostro mortale nemico sin da quando siete arrivato e il suo odio è aumentato dopo il vostro grande successo contro Blefuscu, per il quale la sua gloria di ammiraglio è stata offuscata. Questo gentiluomo e alcuni altri vi hanno accusato di alto tradimento e vari consigli sono stati indetti in gran segreto sul vostro conto. Grato per i vostri favori, mi sono procurato informazioni sull'intero procedimento, rischiando la testa per servirvi, e questo è ciò di cui vi si fa carico:

'Primo, avendo portato la flotta imperiale di Blefuscu nel porto reale, era stato ordinato da Sua Maestà di catturare anche tutte le altre navi e di di mettere a morte tutti gli esiliati Bigendiani e anche la gente dell'impero che non avesse immediatamente acconsentito a rompere le uova dalla parte più piccola. E che, come infido traditore di Sua Serenissima Maestà, vi siete esentato dal servizio fingendo riluttanza ad obbligare la vostra coscienza nel distruggere le libertà e le vite di un popolo innocente.

'D’altronde, quando gli ambasciatori sono giunti dalla Corte di Blefuscu, come un infido traditore, li avete aiutati e intrattenuti, sebbene sapeste che erano i servitori di un principe precedentemente in aperta guerra con Sua Maestà Imperiale.

‘Inoltre, vi state preparando a un viaggio alla corte di Blefuscu, contrariamente al dovere di un suddito fedele.

‘Nella discussione di questa accusa,’ continuò il mio amico ‘Sua Maestà spesso ha messo in evidenza i servigi che gli avete reso mentre l’ammiraglio e il tesoriere insistevano che voi doveste essere messo a morte in modo disonorevole. Ma Reldresal, segretario degli affari privati, che vi ha sempre provato la sua amicizia, ha suggerito che se Sua Maestà si fosse voluto compiacere di risparmiarvi la vita e avesse solo dato ordine di cavarvi entrambi gli occhi, in una certa misura giustizia sarebbe stata fatta. Al che Bolgolam si è alzato furibondo, chiedendo come mai il segretario desiderasse salvare la vita di un traditore; e il tesoriere, puntualizzando la spesa che ci costa mantenervi, anche lui ha chiesto la vostra morte. Ma Sua Maestà si è graziosamente accontentato di dire che siccome il consiglio riteneva la perdita degli occhi una punizione troppo lieve, vene doveva essere inflitta una di qualche altro tipo. E il segretario, chiedendo umilmente si essere ascoltato ancora, ha detto che il vostro mantenimento così costoso avrebbe potuto essere gradatamente ridotto cosicché, a causa del cibo appena sufficiente, voi vi sareste indebolito e sareste morto in pochi mesi, per cui i sudditi di Sua Maestà avrebbero potuto scarnificare le vostre ossa dalla carne e seppellirla, lasciando lo scheletro all’ammirazione dei posteri.

‘Così, grazie alla grande amicizia del segretario, l’affare è stato concluso. È stato ordinato che il piano per affamarvi gradualmente sia mantenuto segreto, ma la sentenza di cavarvi gli occhi era stata registrata nei libri. Entro tre giorni il vostro amico segretario verrà a casa vostra e leggerà l’accusa davanti a voi e mettendo in evidenza la grande misericordia di Sua Maestà, che vi ha solo condannato alla perdita degli occhi, alla quale non ho dubbi vi sottometterete con umiltà e con gratitudine. La eseguiranno venti dei chirurghi di Sua Maestà, per fare in modo che l’operazione si ben condotta, infilandovi frecce assai appuntite negli occhi mentre siete sdraiato sul terreno.

‘Vi lascio’ disse il mio amico ‘a considerare quale misure potrete prendere e, per evitare sospetti, devo fare immediatamente ritorno, in segreto come sono venuto.’

E così fece sua signoria; io rimasi solo, in grande perplessità. Dapprima ero deciso a resistere; mentre ero libero, avrei potuto facilmente fare a pezzi la metropoli con delle pietre, ma subito rigettai l’idea con orrore, rammentando il giuramento fatto all’Imperatore e i favori che avevo ricevuti da lui. Alla fine, avendomi Sua maestà consentito di andare a porgere i miei rispetti all’Imperatore di Blefuscu, decisi di cogliere questa opportunità. Prima che fossero passati i tre giorni, scrissi una lettera al mio amico il segretario, raccontandogli la mia decisione; senza attendere risposta, andai sulla costa ed entrai nel canale; un po’ avanzando a fatica e un po’ nuotando raggiunsi il porto di Blefuscu dove la popolazione, che mi aspettava da tempo, mi condusse alla capitale.

Sua Maestà, con la famiglia reale e i grandi ufficiali di Corte, venne a ricevermi e mi intrattennero in una maniera consona alla generosità di un principe così grande. Ovviamente non feci menzione della mia disgrazia presso l’Imperatore di Lilliput perché finché non avessi potuto supporre che il principe avesse svelato il segreto mentre non ero in suo potere. Ma in ciò ben presto fu chiaro che mi ingannavo.

CAPITOLO V

Tre giorni dopo il mio arrivo, camminando incuriosito sulla costa nordorientale dell’isola, notai a una certa distanza nel mare qualcosa che sembrava una barca capovolta. Mi tolsi le scarpe e le calze e, avanzando per due o trecento iarde, vidi chiaramente che era proprio una barca, che sospettavo una tempesta avesse strappato a una nave. Tornai immediatamente in città in cerca di auto e dopo una gran quantità di lavoro, ottenni di poter portare la barca nel porto reale di Blefuscu, in cui si era riunita una gran folla, piena di meraviglia alla vista del prodigioso vascello. Dissi all’Imperatore che avevo avuto fortuna nel trovare sulla mia strada questa barca che mi avrebbe potuto portare in qualche posto dal quale potessi tornare nel mio paese natale e lo pregai di ordinare il materiale per riparla e e il permesso di partire, cose che fu lieto di concedermi con molte parole gentili.

Nel frattempo l’Imperatore di Lilliput, inquieto per la mia lunga assenza (ma non immaginando che avessi avuto notizia dei suoi disegni) mandò una persona di rango a informare l’Imperatore di Blefuscu della mia disgrazia; questo messaggero ebbe l’ordine di illustrare l grande misericordia del suo signore che si era accontentato di punirmi con la perdita degli occhi e che si aspettava che il suo fratello di Blefuscu mi rimandasse a Lilliput con le mani e i piedi legati, per essere punito come traditore. L’Imperatore di Blefuscu rispose con molte scuse educate. Disse che il volermi indietro legato, il fratello sapeva che fosse impossibile. Inoltre, sebbene avessi portato via la sua flotta, mi era molto grato per i buoni uffici che avevo svolto nella stipula della pace. Ma che entrambe le Maestà l’avrebbero risolta facilmente perché avevo trovato un prodigioso vascello sulla spiaggia, in grado di portarmi in mare, come lui aveva ordinato di fare; e sperava che in poche settimane entrambi gli imperi si sarebbero liberati di me.

Il messaggero tornò a Lilliput con questa risposta e io (sebbene il monarca di Blefuscu mi avesse offerto la sua graziosa protezione se fossi rimasto al suo servizio) affrettai la partenza, decidendo di non fare più molto affidamento sui principi.

In un mese circa fui pronto a salpare. l’Imperatore di Blefuscu con l’Imperatrice e la famiglia reale uscì dal palazzo; io chinai la faccia per baciare loro le mani,che graziosamente mi avevano porto. Sua Maestà mi fece dono di cinquanta borse di sprug (la loro più grande moneta d’oro) e del suo ritratto a figura intera che io deposi immediatamente dentro uno dei miei guanti per preservarlo dagli urti. Molte altre cerimonie ebbero luogo alla mia partenza.

Caricai la barca di cibo e di bevande e presi sei mucche e due tori vivi, così come molte pecore e arieti che intendevo portare nel mio paese,; per nutrirli a bordo avevo una gran quantità di balle di fieno e un sacco di granturco. Avrei portato via volentieri anche una dozzina di nativi, ma questa fu una cosa che l’Imperatore non volle permettere, e dietro diligente ricerca nelle mie tasche, Sua Maestà mi fece promettere sul mio onore che non avrei portato via nessuno dei suoi sudditi neppure con il suo consenso e secondo il suo desiderio.

Avendo preparato tutte le cose meglio che avevo potuto, presi il mare. Quando ebbi fatto ventiquattro leghe, secondo i miei calcoli, vidi giungere una nave da nordest dell’isola di Blefuscu. Gridai un saluto, ma non ottenni risposta, tuttavia notai che avevo guadagnato distanza su di essa perché il vento mi era favorevole; in un’ora e mezza mi avvistò e sparò un colpo di cannone. Eravamo tra le cinque le sei della sera del 26 settembre 1701, ma il mio cuore sobbalzò nel vedere i colori inglesi. Misi in tasca le mucche e i tori e salii a bordo con tutto il mio piccolo carico. Il capitano mi accolse con gentilezza e mi chiese di dirgli da quale luogo venissi; alla mia risposta pensò che vaneggiassi. Così estrassi dalle tasche le mucche nere e le pecore, cosa che lo convinse dopo un grande sbalordimento.

Arrivammo in Inghilterra il 13 aprile 1702. Rimasi per due mesi con mia moglie e la mia famiglia, ma il mio ardente desiderio di vedere paesi stranieri mi impedì di restare più a lungo. Così mentre in Inghilterra guadagnai molto dall’esibizione della mia mandria a persone di qualità e ad altra gente, prima di intraprendere il mio secondo viaggio la vendetti per 600 sterline. Ne lasciai 500 a mia moglie e la sistemai in una bella casa poi mi congedai da lei e dal mio bambino e dalla mia bambina con lacrime da entrambe le parti e salpai a bordo dell’‘Avventura’.

Da I viaggi di Gulliver di Jonathan Swift

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)