The Story of Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Paribanou

(MP3-1h 09' 13'')

There was a sultan, who had three sons and a niece. The eldest of the Princes was called Houssain, the second Ali, the youngest Ahmed, and the Princess, his niece, Nouronnihar.

The Princess Nouronnihar was the daughter of the younger brother of the Sultan, who died, and left the Princess very young. The Sultan took upon himself the care of his daughter’s education, and brought her up in his palace with the three Princes, proposing to marry her when she arrived at a proper age, and to contract an alliance with some neighboring prince by that means. But when he perceived that the three Princes, his sons, loved her passionately, he thought more seriously on that affair. He was very much concerned; the difficulty he foresaw was to make them agree, and that the two youngest should consent to yield her up to their elder brother. As he found them positively obstinate, he sent for them all together, and said to them: “Children, since for your good and quiet I have not been able to persuade you no longer to aspire to the Princess, your cousin, I think it would not be amiss if every one traveled separately into different countries, so that you might not meet each other. And, as you know I am very curious, and delight in everything that’s singular, I promise my niece in marriage to him that shall bring me the most extraordinary rarity; and for the purchase of the rarity you shall go in search after, and the expense of traveling, I will give you every one a sum of money.”

As the three Princes were always submissive and obedient to the Sultan’s will, and each flattered himself fortune might prove favorable to him, they all consented to it. The Sultan paid them the money he promised them; and that very day they gave orders for the preparations for their travels, and took their leave of the Sultan, that they might be the more ready to go the next morning. Accordingly they all set out at the same gate of the city, each dressed like a merchant, attended by an officer of confidence dressed like a slave, and all well mounted and equipped. They went the first day’s journey together, and lay all at an inn, where the road was divided into three different tracts. At night, when they were at supper together, they all agreed to travel for a year, and to meet at that inn; and that the first that came should wait for the rest; that, as they had all three taken their leave together of the Sultan, they might all return together. The next morning by break of day, after they had embraced and wished each other good success, they mounted their horses and took each a different road.

Prince Houssain, the eldest brother, arrived at Bisnagar, the capital of the kingdom of that name, and the residence of its king. He went and lodged at a khan appointed for foreign merchants; and, having learned that there were four principal divisions where merchants of all sorts sold their commodities, and kept shops, and in the midst of which stood the castle, or rather the King’s palace, he went to one of these divisions the next day.

Prince Houssain could not view this division without admiration. It was large, and divided into several streets, all vaulted and shaded from the sun, and yet very light too. The shops were all of a size, and all that dealt in the same sort of goods lived in one street; as also the handicrafts-men, who kept their shops in the smaller streets.

The multitude of shops, stocked with all sorts of merchandise, as the finest linens from several parts of India, some painted in the most lively colors, and representing beasts, trees, and flowers; silks and brocades from Persia, China, and other places, porcelain both from Japan and China, and tapestries, surprised him so much that he knew not how to believe his own eyes; but when he came to the goldsmiths and jewelers he was in a kind of ecstacy to behold such prodigious quantities of wrought gold and silver, and was dazzled by the lustre of the pearls, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and other jewels exposed to sale.

Another thing Prince Houssain particularly admired was the great number of rose-sellers who crowded the streets; for the Indians are so great lovers of that flower that no one will stir without a nosegay in his hand or a garland on his head; and the merchants keep them in pots in their shops, that the air is perfectly perfumed.

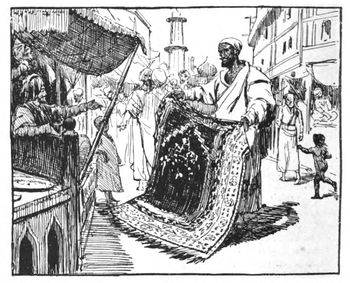

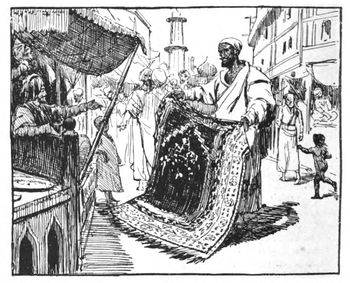

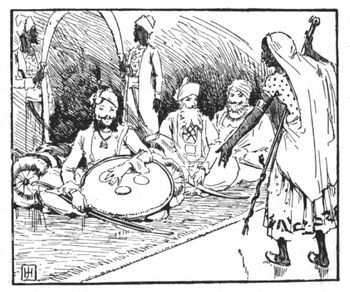

After Prince Houssain had run through that division, street by street, his thoughts fully employed on the riches he had seen, he was very much tired, which a merchant perceiving, civilly invited him to sit down in his shop, and he accepted; but had not been sat down long before he saw a crier pass by with a piece of tapestry on his arm, about six feet square, and cried at thirty purses. The Prince called to the crier, and asked to see the tapestry, which seemed to him to be valued at an exorbitant price, not only for the size of it, but the meanness of the stuff; when he had examined it well, he told the crier that he could not comprehend how so small a piece of tapestry, and of so indifferent appearance, could be set at so high a price.

The crier, who took him for a merchant, replied: “If this price seems so extravagant to you, your amazement will be greater when I tell you I have orders to raise it to forty purses, and not to part with it under.” “Certainly,” answered Prince Houssain, “it must have something very extraordinary in it, which I know nothing of.” “You have guessed it, sir,” replied the crier, “and will own it when you come to know that whoever sits on this piece of tapestry may be transported in an instant wherever he desires to be, without being stopped by any obstacle.”

At this discourse of the crier the Prince of the Indies, considering that the principal motive of his travel was to carry the Sultan, his father, home some singular rarity, thought that he could not meet with any which could give him more satisfaction. “If the tapestry,” said he to the crier, “has the virtue you assign it, I shall not think forty purses too much, but shall make you a present besides.” “Sir,” replied the crier, “I have told you the truth; and it is an easy matter to convince you of it, as soon as you have made the bargain for forty purses, on condition I show you the experiment. But, as I suppose you have not so much about you, and to receive them I must go with you to your khan, where you lodge, with the leave of the master of the shop, we will go into the back shop, and I will spread the tapestry; and when we have both sat down, and you have formed the wish to be transported into your apartment of the khan, if we are not transported thither it shall be no bargain, and you shall be at your liberty. As to your present, though I am paid for my trouble by the seller, I shall receive it as a favor, and be very much obliged to you, and thankful.”

On the credit of the crier, the Prince accepted the conditions, and concluded the bargain; and, having got the master’s leave, they went into his back shop; they both sat down on it, and as soon as the Prince formed his wish to be transported into his apartment at the khan he presently found himself and the crier there; and, as he wanted not a more sufficient proof of the virtue of the tapestry, he counted the crier out forty pieces of gold, and gave him twenty pieces for himself.

In this manner Prince Houssain became the possessor of the tapestry, and was overjoyed that at his arrival at Bisnagar he had found so rare a piece, which he never disputed would gain him the hand of Nouronnihar. In short, he looked upon it as an impossible thing for the Princes his younger brothers to meet with anything to be compared with it. It was in his power, by sitting on his tapestry, to be at the place of meeting that very day; but, as he was obliged to stay there for his brothers, as they had agreed, and as he was curious to see the King of Bisnagar and his Court, and to inform himself of the strength, laws, customs, and religion of the kingdom, he chose to make a longer abode there, and to spend some months in satisfying his curiosity.

Prince Houssain might have made a longer abode in the kingdom and Court of Bisnagar, but he was so eager to be nearer the Princess that, spreading the tapestry, he and the officer he had brought with him sat down, and as soon as he had formed his wish were transported to the inn at which he and his brothers were to meet, and where he passed for a merchant till they came.

Prince Ali, Prince Houssain’s second brother, who designed to travel into Persia, took the road, having three days after he parted with his brothers joined a caravan, and after four days’ travel arrived at Schiraz, which was the capital of the kingdom of Persia. Here he passed for a jeweler.

The next morning Prince Ali, who traveled only for his pleasure, and had brought nothing but just necessaries along with him, after he had dressed himself, took a walk into that part of the town which they at Schiraz called the bezestein.

Among all the criers who passed backward and forward with several sorts of goods, offering to sell them, he was not a little surprised to see one who held an ivory telescope in his hand of about a foot in length and the thickness of a man’s thumb, and cried it at thirty purses. At first he thought the crier mad, and to inform himself went to a shop, and said to the merchant, who stood at the door: “Pray, sir, is not that man” (pointing to the crier who cried the ivory perspective glass at thirty purses) “mad? If he is not, I am very much deceived.”

“Indeed, sir,” answered the merchant, “he was in his right senses yesterday; I can assure you he is one of the ablest criers we have, and the most employed of any when anything valuable is to be sold. And if he cries the ivory perspective glass at thirty purses it must be worth as much or more, on some account or other. He will come by presently, and we will call him, and you shall be satisfied; in the meantime sit down on my sofa, and rest yourself.”

Prince Ali accepted the merchant’s obliging offer, and presently afterward the crier passed by. The merchant called him by his name, and, pointing to the Prince, said to him: “Tell that gentleman, who asked me if you were in your right senses, what you mean by crying that ivory perspective glass, which seems not to be worth much, at thirty purses. I should be very much amazed myself if I did not know you.” The crier, addressing himself to Prince Ali, said: “Sir, you are not the only person that takes me for a madman on account of this perspective glass. You shall judge yourself whether I am or no, when I have told you its property and I hope you will value it at as high a price as those I have showed it to already, who had as bad an opinion of me as you."

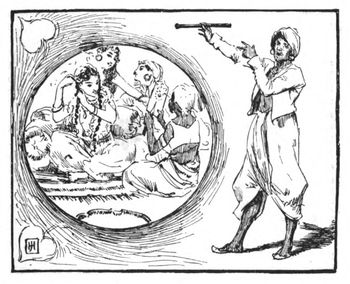

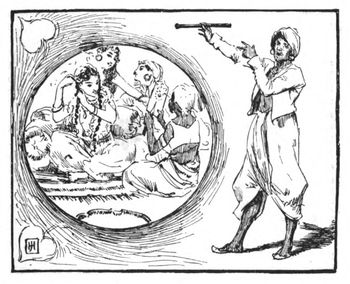

“First, sir,” pursued the crier, presenting the ivory pipe to the Prince, “observe that this pipe is furnished with a glass at both ends; and consider that by looking through one of them you see whatever object you wish to behold.” “I am,” said the Prince, “ready to make you all imaginable reparation for the scandal I have thrown on you if you will make the truth of what you advance appear,” and as he had the ivory pipe in his hand, after he had looked at the two glasses he said: “Show me at which of these ends I must look that I may be satisfied.” The crier presently showed him, and he looked through, wishing at the same time to see the Sultan his father, whom he immediately beheld in perfect health, set on his throne, in the midst of his council. Afterward, as there was nothing in the world so dear to him, after the Sultan, as the Princess Nouronnihar, he wished to see her; and saw her at her toilet laughing, and in a pleasant humor, with her women about her.

Prince Ali wanted no other proof to be persuaded that this perspective glass was the most valuable thing in the world, and believed that if he should neglect to purchase it he should never meet again with such another rarity. He therefore took the crier with him to the khan where he lodged, and counted him out the money, and received the perspective glass.

Prince Ali was overjoyed at his bargain, and persuaded himself that, as his brothers would not be able to meet with anything so rare and admirable, the Princess Nouronnihar would be the recompense of his fatigue and trouble; that he thought of nothing but visiting the Court of Persia incognito, and seeing whatever was curious in Schiraz and thereabouts, till the caravan with which he came returned back to the Indies. As soon as the caravan was ready to set out, the Prince joined them, and arrived happily without any accident or trouble, otherwise than the length of the journey and fatigue of traveling, at the place of rendezvous, where he found Prince Houssain, and both waited for Prince Ahmed.

Prince Ahmed, who took the road of Samarcand, the next day after his arrival there went, as his brothers had done, into the bezestein, where he had not walked long but heard a crier, who had an artificial apple in his hand, cry it at five and thirty purses; upon which he stopped the crier, and said to him: “Let me see that apple, and tell me what virtue and extraordinary properties it has, to be valued at so high a rate.” “Sir,” said the crier, giving it into his hand, “if you look at the outside of this apple, it is very worthless, but if you consider its properties, virtues, and the great use and benefit it is to mankind, you will say it is no price for it, and that he who possesses it is master of a great treasure. In short, it cures all sick persons of the most mortal diseases; and if the patient is dying it will recover him immediately and restore him to perfect health; and this is done after the easiest manner in the world, which is by the patient’s smelling the apple.”

“If I may believe you,” replied Prince Ahmed, “the virtues of this apple are wonderful, and it is invaluable; but what ground have I, for all you tell me, to be persuaded of the truth of this matter?” “Sir,” replied the crier, “the thing is known and averred by the whole city of Samarcand; but, without going any further, ask all these merchants you see here, and hear what they say. You will find several of them will tell you they had not been alive this day if they had not made use of this excellent remedy. And, that you may better comprehend what it is, I must tell you it is the fruit of the study and experiments of a celebrated philosopher of this city, who applied himself all his lifetime to the study and knowledge of the virtues of plants and minerals, and at last attained to this composition, by which he performed such surprising cures in this town as will never be forgot, but died suddenly himself, before he could apply his sovereign remedy, and left his wife and a great many young children behind him, in very indifferent circumstances, who, to support her family and provide for her children, is resolved to sell it.”

While the crier informed Prince Ahmed of the virtues of the artificial apple, a great many persons came about them and confirmed what he said; and one among the rest said he had a friend dangerously ill, whose life was despaired of; and that was a favorable opportunity to show Prince Ahmed the experiment. Upon which Prince Ahmed told the crier he would give him forty purses if he cured the sick person.

The crier, who had orders to sell it at that price, said to Prince Ahmed: “Come, sir, let us go and make the experiment, and the apple shall be yours; and I can assure you that it will always have the desired effect.” In short, the experiment succeeded, and the Prince, after he had counted out to the crier forty purses, and he had delivered the apple to him, waited patiently for the first caravan that should return to the Indies, and arrived in perfect health at the inn where the Princes Houssain and Ali waited for him.

When the Princes met they showed each other their treasures, and immediately saw through the glass that the Princess was dying. They then sat down on the carpet, wished themselves with her, and were there in a moment.

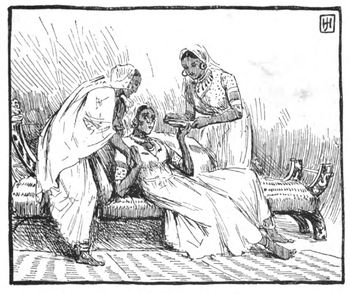

Prince Ahmed no sooner perceived himself in Nouronnihar’s chamber than he rose off the tapestry, as did also the other two Princes, and went to the bedside, and put the apple under her nose; some moments after the Princess opened her eyes, and turned her head from one side to another, looking at the persons who stood about her; and then rose up in the bed, and asked to be dressed, just as if she had waked out of a sound sleep. Her women having presently informed her, in a manner that showed their joy, that she was obliged to the three Princes for the sudden recovery of her health, and particularly to Prince Ahmed; she immediately expressed her joy to see them, and thanked them all together, and afterward Prince Ahmed in particular.

While the Princess was dressing the Princes went to throw themselves at the Sultan their father’s feet, and pay their respects to him. But when they came before him they found he had been informed of their arrival by the chief of the Princess’s eunuchs, and by what means the Princess had been perfectly cured. The Sultan received and embraced them with the greatest joy, both for their return and the recovery of the Princess his niece, whom he loved as well as if she had been his own daughter, and who had been given over by the physicians. After the usual ceremonies and compliments the Princes presented each his rarity: Prince Houssain his tapestry, which he had taken care not to leave behind him in the Princess’s chamber; Prince Ali his ivory perspective glass, and Prince Ahmed his artificial apple; and after each had commended their present, when they put it into the Sultan’s hands, they begged of him to pronounce their fate, and declare to which of them he would give the Princess Nouronnihar for a wife, according to his promise.

The Sultan of the Indies, having heard, without interrupting them, all that the Princes could represent further about their rarities, and being well informed of what had happened in relation to the Princess Nouronnihar’s cure, remained some time silent, as if he were thinking on what answer he should make. At last he broke the silence, and said to them: “I would declare for one of you children with a great deal of pleasure if I could do it with justice; but consider whether I can do it or no. ‘Tis true, Prince Ahmed, the Princess my niece is obliged to your artificial apple for her cure; but I must ask you whether or no you could have been so serviceable to her if you had not known by Prince Ali’s perspective glass the danger she was in, and if Prince Houssain’s tapestry had not brought you so soon. Your perspective glass, Prince Ali, informed you and your brothers that you were like to lose the Princess your cousin, and there you must own a great obligation.

“You must also grant that that knowledge would have been of no service without the artificial apple and the tapestry. And lastly, Prince Houssain, the Princess would be very ungrateful if she should not show her acknowledgment of the service of your tapestry, which was so necessary a means toward her cure. But consider, it would have been of little use if you had not been acquainted with the Princess’s illness by Prince Ali’s glass, and Prince Ahmed had not applied his artificial apple. Therefore, as neither tapestry, ivory perspective glass, nor artificial apple have the least preference one before the other, but, on the contrary, there’s a perfect equality, I cannot grant the Princess to any one of you; and the only fruit you have reaped from your travels is the glory of having equally contributed to restore her health.

“If all this be true,” added the Sultan, “you see that I must have recourse to other means to determine certainly in the choice I ought to make among you; and that, as there is time enough between this and night, I’ll do it to-day. Go and get each of you a bow and arrow, and repair to the great plain, where they exercise horses. I’ll soon come to you, and declare I will give the Princess Nouronnihar to him that shoots the farthest.”

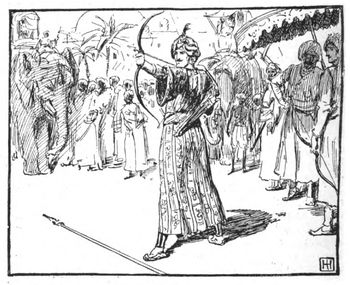

The three Princes had nothing to say against the decision of the Sultan. When they were out of his presence they each provided themselves with a bow and arrow, which they delivered to one of their officers, and went to the plain appointed, followed by a great concourse of people.

The Sultan did not make them wait long for him, and as soon as he arrived Prince Houssain, as the eldest, took his bow and arrow and shot first; Prince Ali shot next, and much beyond him; and Prince Ahmed last of all, but it so happened that nobody could see where his arrow fell; and, notwithstanding all the diligence that was used by himself and everybody else, it was not to be found far or near.

And though it was believed that he shot the farthest, and that he therefore deserved the Princess Nouronnihar, it was, however, necessary that his arrow should be found to make the matter more evident and certain; and, notwithstanding his remonstrance, the Sultan judged in favor of Prince Ali, and gave orders for preparations to be made for the wedding, which was celebrated a few days after with great magnificence.

Prince Houssain would not honor the feast with his presence. In short, his grief was so violent and insupportable that he left the Court, and renounced all right of succession to the crown, to turn hermit.

Prince Ahmed, too, did not come to Prince Ali’s and the Princess Nouronnihar’s wedding any more than his brother Houssain, but did not renounce the world as he had done. But, as he could not imagine what had become of his arrow, he stole away from his attendants and resolved to search after it, that he might not have anything to reproach himself with. With this intent he went to the place where the Princes Houssain’s and Ali’s were gathered up, and, going straight forward from there, looking carefully on both sides of him, he went so far that at last he began to think his labor was all in vain; but yet he could not help going forward till he came to some steep craggy rocks, which were bounds to his journey, and were situated in a barren country, about four leagues distant from where he set out.

II

When Prince Ahmed came pretty nigh to these rocks he perceived an arrow, which he gathered up, looked earnestly at it, and was in the greatest astonishment to find it was the same he shot away. “Certainly,” said he to himself, “neither I nor any man living could shoot an arrow so far,” and, finding it laid flat, not sticking into the ground, he judged that it rebounded against the rock. “There must be some mystery in this,” said he to himself again, “and it may be advantageous to me. Perhaps fortune, to make me amends for depriving me of what I thought the greatest happiness, may have reserved a greater blessing for my comfort.”

As these rocks were full of caves and some of those caves were deep, the Prince entered into one, and, looking about, cast his eyes on an iron door, which seemed to have no lock, but he feared it was fastened. However, thrusting against it, it opened, and discovered an easy descent, but no steps, which he walked down with his arrow in his hand. At first he thought he was going into a dark, obscure place, but presently a quite different light succeeded that which he came out of, and, entering into a large, spacious place, at about fifty or sixty paces distant, he perceived a magnificent palace, which he had not then time enough to look at. At the same time a lady of majestic port and air advanced as far as the porch, attended by a large troop of ladies, so finely dressed and beautiful that it was difficult to distinguish which was the mistress.

As soon as Prince Ahmed perceived the lady, he made all imaginable haste to go and pay his respects; and the lady, on her part, seeing him coming, prevented him from addressing his discourse to her first, but said to him: “Come nearer, Prince Ahmed, you are welcome.”

It was no small surprise to the Prince to hear himself named in a place he had never heard of, though so nigh to his father’s capital, and he could not comprehend how he should be known to a lady who was a stranger to him. At last he returned the lady’s compliment by throwing himself at her feet, and, rising up again, said to her:

“Madam, I return you a thousand thanks for the assurance you give me of a welcome to a place where I believed my imprudent curiosity had made me penetrate too far. But, madam, may I, without being guilty of ill manners, dare to ask you by what adventure you know me? and how you, who live in the same neighborhood with me, should be so great a stranger to me?”

“Prince,” said the lady, “let us go into the hall, there I will gratify you in your request.”

After these words the lady led Prince Ahmed into the hall. Then she sat down on a sofa, and when the Prince by her entreaty had done the same she said: “You are surprised, you say, that I should know you and not be known by you, but you will be no longer surprised when I inform you who I am. You are undoubtedly sensible that your religion teaches you to believe that the world is inhabited by genies as well as men. I am the daughter of one of the most powerful and distinguished genies, and my name is Paribanou. The only thing that I have to add is, that you seemed to me worthy of a more happy fate than that of possessing the Princess Nouronnihar; and, that you might attain to it, I was present when you drew your arrow, and foresaw it would not go beyond Prince Houssain’s. I took it in the air, and gave it the necessary motion to strike against the rocks near which you found it, and I tell you that it lies in your power to make use of the favorable opportunity which presents itself to make you happy.”

As the Fairy Paribanou pronounced these last words with a different tone, and looked, at the same time, tenderly upon Prince Ahmed, with a modest blush on her cheeks, it was no hard matter for the Prince to comprehend what happiness she meant. He presently considered that the Princess Nouronnihar could never be his and that the Fairy Paribanou excelled her infinitely in beauty, agreeableness, wit, and, as much as he could conjecture by the magnificence of the palace, in immense riches. He blessed the moment that he thought of seeking after his arrow a second time, and, yielding to his love, “Madam,” replied he, “should I all my life have the happiness of being your slave, and the admirer of the many charms which ravish my soul, I should think myself the most blessed of men. Pardon in me the boldness which inspires me to ask this favor, and don’t refuse to admit me into your Court, a prince who is entirely devoted to you.”

“Prince,” answered the Fairy, “will you not pledge your faith to me, as well as I give mine to you?” “Yes, madam,” replied the Prince, in an ecstacy of joy; “what can I do better, and with greater pleasure? Yes, my sultaness, my queen, I’ll give you my heart without the least reserve.” “Then,” answered the Fairy, “you are my husband, and I am your wife. But, as I suppose,” pursued she, “that you have eaten nothing to-day, a slight repast shall be served up for you, while preparations are making for our wedding feast at night, and then I will show you the apartments of my palace, and you shall judge if this hall is not the meanest part of it.”

Some of the Fairy’s women, who came into the hall with them, and guessed her intentions, went immediately out, and returned presently with some excellent meats and wines.

When Prince Ahmed had ate and drunk as much as he cared for, the Fairy Paribanou carried him through all the apartments, where he saw diamonds, rubies, emeralds and all sorts of fine jewels, intermixed with pearls, agate, jasper, porphyry, and all sorts of the most precious marbles. But, not to mention the richness of the furniture, which was inestimable, there was such a profuseness throughout that the Prince, instead of ever having seen anything like it, owned that he could not have imagined that there was anything in the world that could come up to it. “Prince,” said the Fairy, “if you admire my palace so much, which, indeed, is very beautiful, what would you say to the palaces of the chief of our genies, which are much more beautiful, spacious, and magnificent? I could also charm you with my gardens, but we will let that alone till another time. Night draws near, and it will be time to go to supper.”

The next hall which the Fairy led the Prince into, and where the cloth was laid for the feast, was the last apartment the Prince had not seen, and not in the least inferior to the others. At his entrance into it he admired the infinite number of sconces of wax candles perfumed with amber, the multitude of which, instead of being confused, were placed with so just a symmetry as formed an agreeable and pleasant sight. A large side table was set out with all sorts of gold plate, so finely wrought that the workmanship was much more valuable than the weight of the gold. Several choruses of beautiful women richly dressed, and whose voices were ravishing, began a concert, accompanied with all sorts of the most harmonious instruments; and when they were set down at table the Fairy Paribanou took care to help Prince Ahmed to the most delicate meats, which she named as she invited him to eat of them, and which the Prince found to be so exquisitely nice that he commended them with exaggeration, and said that the entertainment far surpassed those of man. He found also the same excellence in the wines, which neither he nor the Fairy tasted of till the dessert was served up, which consisted of the choicest sweetmeats and fruits.

The wedding feast was continued the next day, or, rather, the days following the celebration were a continual feast.

At the end of six months Prince Ahmed, who always loved and honored the Sultan his father, conceived a great desire to know how he was, and that desire could not be satisfied without his going to see; he told the Fairy of it, and desired she would give him leave.

“Prince,” said she, “go when you please. But first, don’t take it amiss that I give you some advice how you shall behave yourself where you are going. First, I don’t think it proper for you to tell the Sultan your father of our marriage, nor of my quality, nor the place where you have been. Beg of him to be satisfied in knowing you are happy, and desire no more; and let him know that the sole end of your visit is to make him easy, and inform him of your fate.”

She appointed twenty gentlemen, well mounted and equipped, to attend him. When all was ready Prince Ahmed took his leave of the Fairy, embraced her, and renewed his promise to return soon. Then his horse, which was most finely caparisoned, and was as beautiful a creature as any in the Sultan of Indies’ stables, was led to him, and he mounted him with an extraordinary grace; and, after he had bid her a last adieu, set forward on his journey.

As it was not a great way to his father’s capital, Prince Ahmed soon arrived there. The people, glad to see him again, received him with acclamations of joy, and followed him in crowds to the Sultan’s apartment. The Sultan received and embraced him with great joy, complaining at the same time, with a fatherly tenderness, of the affliction his long absence had been to him, which he said was the more grievous for that, fortune having decided in favor of Prince Ali his brother, he was afraid he might have committed some rash action.

The Prince told a story of his adventures without speaking of the Fairy, whom he said that he must not mention, and ended: “The only favor I ask of your Majesty is to give me leave to come often and pay you my respects, and to know how you do.”

“Son,” answered the Sultan of the Indies, “I cannot refuse you the leave you ask me; but I should much rather you would resolve to stay with me; at least tell me where I may send to you if you should fail to come, or when I may think your presence necessary.” “Sir,” replied Prince Ahmed, “what your Majesty asks of me is part of the mystery I spoke to your Majesty of. I beg of you to give me leave to remain silent on this head, for I shall come so frequently that I am afraid that I shall sooner be thought troublesome than be accused of negligence in my duty.”

The Sultan of the Indies pressed Prince Ahmed no more, but said to him: “Son, I penetrate no farther into your secrets, but leave you at your liberty; but can tell you that you could not do me a greater pleasure than to come, and by your presence restore to me the joy I have not felt this long time, and that you shall always be welcome when you come, without interrupting your business or pleasure.”

Prince Ahmed stayed but three days at the Sultan his father’s Court, and the fourth returned to the Fairy Paribanou, who did not expect him so soon.

A month after Prince Ahmed’s return from paying a visit to his father, as the Fairy Paribanou had observed that the Prince, since the time that he gave her an account of his journey, his discourse with his father, and the leave he asked to go and see him often, had never talked of the Sultan, as if there had been no such person in the world, whereas before he was always speaking of him, she thought he forebore on her account; therefore she took an opportunity to say to him one day: “Prince, tell me, have you forgot the Sultan your father? Don’t you remember the promise you made to go and see him often? For my part I have not forgot what you told me at your return, and so put you in mind of it, that you may not be long before you acquit yourself of your promise.”

So Prince Ahmed went the next morning with the same attendance as before, but much finer, and himself more magnificently mounted, equipped, and dressed, and was received by the Sultan with the same joy and satisfaction. For several months he constantly paid his visits, always in a richer and finer equipage.

At last some viziers, the Sultan’s favorites, who judged of Prince Ahmed’s grandeur and power by the figure he cut, made the Sultan jealous of his son, saying it was to be feared he might inveigle himself into the people’s favor and dethrone him.

The Sultan of the Indies was so far from thinking that Prince Ahmed could be capable of so pernicious a design as his favorites would make him believe that he said to them: “You are mistaken; my son loves me, and I am certain of his tenderness and fidelity, as I have given him no reason to be disgusted.”

But the favorites went on abusing Prince Ahmed till the Sultan said: “Be it as it will, I don’t believe my son Ahmed is so wicked as you would persuade me he is; how ever, I am obliged to you for your good advice, and don’t dispute but that it proceeds from your good intentions.”

The Sultan of the Indies said this that his favorites might not know the impressions their discourse had made on his mind; which had so alarmed him that he resolved to have Prince Ahmed watched unknown to his grand vizier. So he sent for a female magician, who was introduced by a back door into his apartment. “Go immediately,” he said, “and follow my son, and watch him so well as to find out where he retires, and bring me word.”

The magician left the Sultan, and, knowing the place where Prince Ahmed found his arrow, went immediately thither, and hid herself near the rocks, so that nobody could see her.

The next morning Prince Ahmed set out by daybreak, without taking leave either of the Sultan or any of his Court, according to custom. The magician, seeing him coming, followed him with her eyes, till on a sudden she lost sight of him and his attendants.

As the rocks were very steep and craggy, they were an insurmountable barrier, so that the magician judged that there were but two things for it: either that the Prince retired into some cavern, or an abode of genies or fairies. Thereupon she came out of the place where she was hid and went directly to the hollow way, which she traced till she came to the farther end, looking carefully about on all sides; but, notwithstanding all her diligence, could perceive no opening, not so much as the iron gate which Prince Ahmed discovered, which was to be seen and opened to none but men, and only to such whose presence was agreeable to the Fairy Paribanou.

The magician, who saw it was in vain for her to search any farther, was obliged to be satisfied with the discovery she had made, and returned to give the Sultan an account.

The Sultan was very well pleased with the magician’s conduct, and said to her: “Do you as you think fit; I’ll wait patiently the event of your promises,” and to encourage her made her a present of a diamond of great value.

As Prince Ahmed had obtained the Fairy Paribanou’s leave to go to the Sultan of the Indies’ Court once a month, he never failed, and the magician, knowing the time, went a day or two before to the foot of the rock where she lost sight of the Prince and his attendants, and waited there.

The next morning Prince Ahmed went out, as usual, at the iron gate, with the same attendants as before, and passed by the magician, whom he knew not to be such, and, seeing her lie with her head against the rock, and complaining as if she were in great pain, he pitied her, turned his horse about, went to her, and asked her what was the matter with her, and what he could do to ease her.

The artful sorceress looked at the Prince in a pitiful manner, without ever lifting up her head, and answered in broken words and sighs, as if she could hardly fetch her breath, that she was going to the capital city, but on the way thither she was taken with so violent a fever that her strength failed her, and she was forced to lie down where he saw her, far from any habitation, and without any hopes of assistance.

“Good woman,” replied Prince Ahmed, “you are not so far from help as you imagine. I am ready to assist you, and convey you where you will meet with a speedy cure; only get up, and let one of my people take you behind him.”

At these words the magician, who pretended sickness only to know where the Prince lived and what he did, refused not the charitable offer he made her, and that her actions might correspond with her words she made many pretended vain endeavors to get up. At the same time two of the Prince’s attendants, alighting off their horses, helped her up, and set her behind another, and mounted their horses again, and followed the Prince, who turned back to the iron gate, which was opened by one of his retinue who rode before. And when he came into the outward court of the Fairy, without dismounting himself, he sent to tell her he wanted to speak with her.

The Fairy Paribanou came with all imaginable haste, not knowing what made Prince Ahmed return so soon, who, not giving her time to ask him the reason, said: “Princess, I desire you would have compassion on this good woman,” pointing to the magician, who was held up by two of his retinue. “I found her in the condition you see her in, and promised her the assistance she stands in need of, and am persuaded that you, out of your own goodness, as well as upon my entreaty, will not abandon her.”

The Fairy Paribanou, who had her eyes fixed upon the pretended sick woman all the time that the Prince was talking to her, ordered two of her women who followed her to take her from the two men that held her, and carry her into an apartment of the palace, and take as much care of her as she would herself.

While the two women executed the Fairy’s commands, she went up to Prince Ahmed, and, whispering in his ear, said: “Prince, this woman is not so sick as she pretends to be; and I am very much mistaken if she is not an impostor, who will be the cause of a great trouble to you. But don’t be concerned, let what will be devised against you; be persuaded that I will deliver you out of all the snares that shall be laid for you. Go and pursue your journey.”

This discourse of the Fairy’s did not in the least frighten Prince Ahmed. “My Princess,” said he, “as I do not remember I ever did or designed anybody an injury, I cannot believe anybody can have a thought of doing me one, but if they have I shall not, nevertheless, forbear doing good whenever I have an opportunity.” Then he went back to his father’s palace.

In the meantime the two women carried the magician into a very fine apartment, richly furnished. First they sat her down upon a sofa, with her back supported with a cushion of gold brocade, while they made a bed on the same sofa before her, the quilt of which was finely embroidered with silk, the sheets of the finest linen, and the coverlet cloth-of-gold. When they had put her into bed (for the old sorceress pretended that her fever was so violent she could not help herself in the least) one of the women went out, and returned soon again with a china dish in her hand, full of a certain liquor, which she presented to the magician, while the other helped her to sit up. “Drink this liquor,” said she; “it is the Water of the Fountain of Lions, and a sovereign remedy against all fevers whatsoever. You will find the effect of it in less than an hour’s time.”

The magician, to dissemble the better, took it after a great deal of entreaty; but at last she took the china dish, and, holding back her head, swallowed down the liquor. When she was laid down again the two women covered her up. “Lie quiet,” said she who brought her the china cup, “and get a little sleep if you can. We’ll leave you, and hope to find you perfectly cured when we come again an hour hence.”

The two women came again at the time they said they should, and found the magician up and dressed, and sitting upon the sofa. “Oh, admirable potion!” she said: “it has wrought its cure much sooner than you told me it would, and I shall be able to prosecute my journey.”

The two women, who were fairies as well as their mistress, after they had told the magician how glad they were that she was cured so soon, walked before her, and conducted her through several apartments, all more noble than that wherein she lay, into a large hall, the most richly and magnificently furnished of all the palace.

Fairy Paribanou sat in this hall on a throne of massive gold, enriched with diamonds, rubies, and pearls of an extraordinary size, and attended on each hand by a great number of beautiful fairies, all richly clothed. At the sight of so much majesty, the magician was not only dazzled, but was so amazed that, after she had prostrated herself before the throne, she could not open her lips to thank the Fairy as she proposed. However, Paribanou saved her the trouble, and said to her: “Good woman, I am glad I had an opportunity to oblige you, and to see you are able to pursue your journey. I won’t detain you, but perhaps you may not be displeased to see my palace; follow my women, and they will show it you.”

Then the magician went back and related to the Sultan of the Indies all that had happened, and how very rich Prince Ahmed was since his marriage with the Fairy, richer than all the kings in the world, and how there was danger that he should come and take the throne from his father.

Though the Sultan of the Indies was very well persuaded that Prince Ahmed’s natural disposition was good, yet he could not help being concerned at the discourse of the old sorceress, to whom, when she was taking her leave, he said: “I thank thee for the pains thou hast taken, and thy wholesome advice. I am so sensible of the great importance it is to me that I shall deliberate upon it in council.”

Now the favorites advised that the Prince should be killed, but the magician advised differently: “Make him give you all kinds of wonderful things, by the Fairy’s help, till she tires of him and sends him away. As, for example, every time your Majesty goes into the field, you are obliged to be at a great expense, not only in pavilions and tents for your army, but likewise in mules and camels to carry their baggage. Now, might not you engage him to use his interest with the Fairy to procure you a tent which might be carried in a man’s hand, and which should be so large as to shelter your whole army against bad weather?”

When the magician had finished her speech, the Sultan asked his favorites if they had anything better to propose; and, finding them all silent, determined to follow the magician’s advice, as the most reasonable and most agreeable to his mild government.

Next day the Sultan did as the magician had advised him, and asked for the pavilion.

Prince Ahmed never expected that the Sultan his father would have asked such a thing, which at first appeared so difficult, not to say impossible. Though he knew not absolutely how great the power of genies and fairies was, he doubted whether it extended so far as to compass such a tent as his father desired. At last he replied: “Though it is with the greatest reluctance imaginable, I will not fail to ask the favor of my wife your Majesty desires, but will not promise you to obtain it; and if I should not have the honor to come again to pay you my respects that shall be the sign that I have not had success. But beforehand, I desire you to forgive me, and consider that you yourself have reduced me to this extremity.”

“Son,” replied the Sultan of the Indies, “I should be very sorry if what I ask of you should cause me the displeasure of never seeing you more. I find you don’t know the power a husband has over a wife; and yours would show that her love to you was very indifferent if she, with the power she has of a fairy, should refuse you so trifling a request as this I desire you to ask of her for my sake.” The Prince went back, and was very sad for fear of offending the Fairy. She kept pressing him to tell her what was the matter, and at last he said: “Madam, you may have observed that hitherto I have been content with your love, and have never asked you any other favor. Consider then, I conjure you, that it is not I, but the Sultan my father, who indiscreetly, or at least I think so, begs of you a pavilion large enough to shelter him, his Court, and army from the violence of the weather, and which a man may carry in his hand. But remember it is the Sultan my father asks this favor.”

“Prince,” replied the Fairy, smiling, “I am sorry that so small a matter should disturb you, and make you so uneasy as you appeared to me.”

Then the Fairy sent for her treasurer, to whom, when she came, she said: “Nourgihan”—which was her name—“bring me the largest pavilion in my treasury.” Nourgiham returned presently with the pavilion, which she could not only hold in her hand, but in the palm of her hand when she shut her fingers, and presented it to her mistress, who gave it to Prince Ahmed to look at.

When Prince Ahmed saw the pavilion which the Fairy called the largest in her treasury, he fancied she had a mind to jest with him, and thereupon the marks of his surprise appeared presently in his countenance; which Paribanou perceiving burst out laughing. “What! Prince,” cried she, “do you think I jest with you? You’ll see presently that I am in earnest. Nourgihan,” said she to her treasurer, taking the tent out of Prince Ahmed’s hands, “go and set it up, that the Prince may judge whether it may be large enough for the Sultan his father.”

The treasurer went immediately with it out of the palace, and carried it a great way off; and when she had set it up one end reached to the very palace; at which time the Prince, thinking it small, found it large enough to shelter two greater armies than that of the Sultan his father’s, and then said to Paribanou: “I ask my Princess a thousand pardons for my incredulity; after what I have seen I believe there is nothing impossible to you.” “You see,” said the Fairy, “that the pavilion is larger than what your father may have occasion for; for you must know that it has one property—that it is larger or smaller according to the army it is to cover.”

The treasurer took down the tent again, and brought it to the Prince, who took it, and, without staying any longer than till the next day, mounted his horse, and went with the same attendants to the Sultan his father.

The Sultan, who was persuaded that there could not be any such thing as such a tent as he asked for, was in a great surprise at the Prince’s diligence. He took the tent and after he had admired its smallness his amazement was so great that he could not recover himself. When the tent was set up in the great plain, which we have before mentioned, he found it large enough to shelter an army twice as large as he could bring into the field.

But the Sultan was not yet satisfied. “Son,” said he, “I have already expressed to you how much I am obliged to you for the present of the tent you have procured me; that I look upon it as the most valuable thing in all my treasury. But you must do one thing more for me, which will be every whit as agreeable to me. I am informed that the Fairy, your spouse, makes use of a certain water, called the Water of the Fountain of Lions, which cures all sorts of fevers, even the most dangerous, and, as I am perfectly well persuaded my health is dear to you, I don’t doubt but you will ask her for a bottle of that water for me, and bring it me as a sovereign medicine, which I may make use of when I have occasion. Do me this other important piece of service, and thereby complete the duty of a good son toward a tender father.”

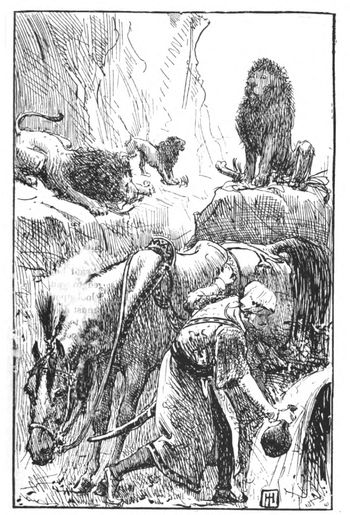

The Prince returned and told the Fairy what his father had said; “There’s a great deal of wickedness in this demand,” she answered, “as you will understand by what I am going to tell you. The Fountain of Lions is situated in the middle of a court of a great castle, the entrance into which is guarded by four fierce lions, two of which sleep alternately, while the other two are awake. But don’t let that frighten you: I’ll give you means to pass by them without any danger.”

The Fairy Paribanou was at that time very hard at work, and, as she had several clews of thread by her, she took up one, and, presenting it to Prince Ahmed, said: “First take this clew of thread. I’ll tell you presently the use of it. In the second place, you must have two horses; one you must ride yourself, and the other you must lead, which must be loaded with a sheep cut into four quarters, that must be killed to-day. In the third place, you must be provided with a bottle, which I will give you, to bring the water in. Set out early to-morrow morning, and when you have passed the iron gate throw the clew of thread before you, which will roll till it comes to the gates of the castle. Follow it, and when it stops, as the gates will be open, you will see the four lions: the two that are awake will, by their roaring, wake the other two, but don’t be frightened, but throw each of them a quarter of mutton, and then clap spurs to your horse and ride to the fountain; fill your bottle without alighting, and then return with the same expedition. The lions will be so busy eating they will let you pass by them.”

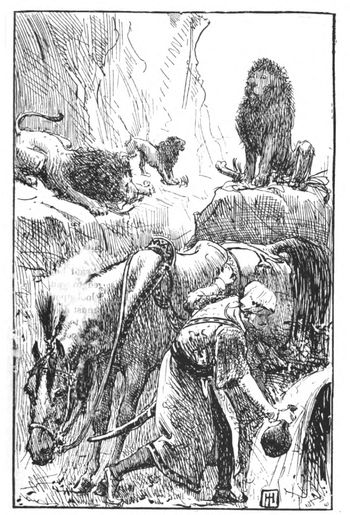

Prince Ahmed set out the next morning at the time appointed by the Fairy, and followed her directions exactly. When he arrived at the gates of the castle he distributed the quarters of mutton among the four lions, and, passing through the midst of them bravely, got to the fountain, filled his bottle, and returned back as safe and sound as he went.

When he had gone a little distance from the castle gates he turned him about, and, perceiving two of the lions coming after him, he drew his sabre and prepared himself for defense. But as he went forward he saw one of them turned out of the road at some distance, and showed by his head and tail that he did not come to do him any harm, but only to go before him, and that the other stayed behind to follow, he put his sword up again in its scabbard. Guarded in this manner, he arrived at the capital of the Indies, but the lions never left him till they had conducted him to the gates of the Sultan’s palace; after which they returned the same way they came, though not without frightening all that saw them, for all they went in a very gentle manner and showed no fierceness.

A great many officers came to attend the Prince while he dismounted his horse, and afterward conducted him into the Sultan’s apartment, who was at that time surrounded with his favorites. He approached toward the throne, laid the bottle at the Sultan’s feet, and kissed the rich tapestry which covered his footstool, and then said:

“I have brought you, sir, the healthful water which your Majesty desired so much to keep among your other rarities in your treasury, but at the same time wish you such extraordinary health as never to have occasion to make use of it.”

After the Prince had made an end of his compliment the Sultan placed him on his right hand, and then said to him: “Son, I am very much obliged to you for this valuable present, as also for the great danger you have exposed yourself to upon my account (which I have been informed of by a magician who knows the Fountain of Lions); but do me the pleasure,” continued he, “to inform me by what address, or, rather, by what incredible power, you have been secured.”

“Sir,” replied Prince Ahmed, “I have no share in the compliment your Majesty is pleased to make me; all the honor is due to the Fairy my spouse, whose good advice I followed.” Then he informed the Sultan what those directions were, and by the relation of this his expedition let him know how well he had behaved himself. When he had done the Sultan, who showed outwardly all the demonstrations of great joy, but secretly became more jealous, retired into an inward apartment, where he sent for the magician.

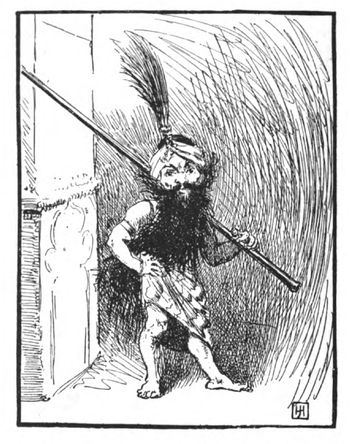

The magician, at her arrival, saved the Sultan the trouble to tell her of the success of Prince Ahmed’s journey, which she had heard of before she came, and therefore was prepared with an infallible means, as she pretended. This means she communicated to the Sultan who declared it the next day to the Prince, in the midst of all his courtiers, in these words: “Son,” said he, “I have one thing more to ask of you, after which I shall expect nothing more from your obedience, nor your interest with your wife. This request is, to bring me a man not above a foot and a half high, and whose beard is thirty feet long who carries a bar of iron upon his shoulders of five hundredweight, which he uses as a quarterstaff.”

Prince Ahmed, who did not believe that there was such a man in the world as his father described, would gladly have excused himself; but the Sultan persisted in his demand, and told him the Fairy could do more incredible things.

The next day the Prince returned to his dear Paribanou, to whom he told his father’s new demand, which, he said, he looked upon to be a thing more impossible than the two first; “for,” added he, “I cannot imagine there can be such a man in the world; without doubt, he has a mind to try whether or no I am so silly as to go about it, or he has a design on my ruin. In short, how can he suppose that I should lay hold of a man so well armed, though he is but little? What arms can I make use of to reduce him to my will? If there are any means, I beg you will tell them, and let me come off with honor this time.”

“Don’t affright yourself, Prince,” replied the Fairy; “you ran a risk in fetching the Water of the Fountain of Lions for your father, but there’s no danger in finding out this man, who is my brother Schaibar, but is so far from being like me, though we both had the same father, that he is of so violent a nature that nothing can prevent his giving cruel marks of his resentment for a slight offense; yet, on the other hand, is so good as to oblige anyone in whatever they desire. He is made exactly as the Sultan your father has described him, and has no other arms than a bar of iron of five hundred pounds weight, without which he never stirs, and which makes him respected. I’ll send for him, and you shall judge of the truth of what I tell you; but be sure to prepare yourself against being frightened at his extraordinary figure when you see him.” “What! my Queen,” replied Prince Ahmed, “do you say Schaibar is your brother? Let him be never so ugly or deformed I shall be so far from being frightened at the sight of him that, as our brother, I shall honor and love him.”

The Fairy ordered a gold chafing-dish to be set with a fire in it under the porch of her palace, with a box of the same metal, which was a present to her, out of which taking a perfume, and throwing it into the fire, there arose a thick cloud of smoke.

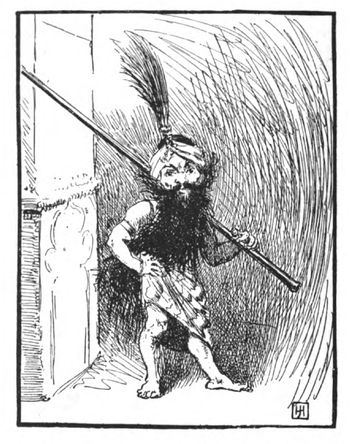

Some moments after the Fairy said to Prince Ahmed: “See, there comes my brother.” The Prince immediately perceived Schaibar coming gravely with his heavy bar on his shoulder, his long beard, which he held up before him, and a pair of thick mustachios, which he tucked behind his ears and almost covered his face; his eyes were very small and deep-set in his head, which was far from being of the smallest size, and on his head he wore a grenadier’s cap; besides all this, he was very much hump-backed.

If Prince Ahmed had not known that Schaibar was Paribanou’s brother, he would not have been able to have looked at him without fear, but, knowing first who he was, he stood by the Fairy without the least concern.

Schaibar, as he came forward, looked at the Prince earnestly enough to have chilled his blood in his veins, and asked Paribanou, when he first accosted her, who that man was. To which she replied: “He is my husband, brother. His name is Ahmed; he is son to the Sultan of the Indies. The reason why I did not invite you to my wedding was I was unwilling to divert you from an expedition you were engaged in, and from which I heard with pleasure you returned victorious, and so took the liberty now to call for you.”

At these words, Schaibar, looking on Prince Ahmed favorably, said: “Is there anything else, sister, wherein I can serve him? It is enough for me that he is your husband to engage me to do for him whatever he desires.” “The Sultan, his father,” replied Paribanou, “has a curiosity to see you, and I desire he may be your guide to the Sultan’s Court.” “He needs but lead me the way I’ll follow him.” “Brother,” replied Paribanou, “it is too late to go to-day, therefore stay till to-morrow morning; and in the meantime I’ll inform you of all that has passed between the Sultan of the Indies and Prince Ahmed since our marriage.”

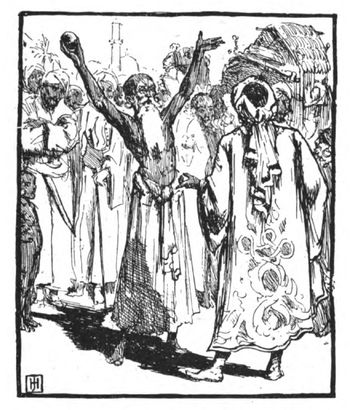

The next morning, after Schaibar had been informed of the affair, he and Prince Ahmed set out for the Sultan’s Court. When they arrived at the gates of the capital the people no sooner saw Schaibar but they ran and hid themselves; and some shut up their shops and locked themselves up in their houses, while others, flying, communicated their fear to all they met, who stayed not to look behind them, but ran too; insomuch that Schaibar and Prince Ahmed, as they went along, found the streets all desolate till they came to the palaces where the porters, instead of keeping the gates, ran away too, so that the Prince and Schaibar advanced without any obstacle to the council-hall, where the Sultan was seated on his throne, and giving audience. Here likewise the ushers, at the approach of Schaibar, abandoned their posts, and gave them free admittance.

Schaibar went boldly and fiercely up to the throne, without waiting to be presented by Prince Ahmed, and accosted the Sultan of the Indies in these words: “Thou hast asked for me,” said he; “see, here I am; what wouldst thou have with me?”

The Sultan, instead of answering him, clapped his hands before his eyes to avoid the sight of so terrible an object; at which uncivil and rude reception Schaibar was so much provoked, after he had given him the trouble to come so far, that he instantly lifted up his iron bar and killed him before Prince Ahmed could intercede in his behalf. All that he could do was to prevent his killing the grand vizier, who sat not far from him, representing to him that he had always given the Sultan his father good advice.

“These are they, then,” said Schaibar, “who gave him bad,” and as he pronounced these words he killed all the other viziers and flattering favorites of the Sultan who were Prince Ahmed’s enemies. Every time he struck he killed some one or other, and none escaped but they who were not so frightened as to stand staring and gaping, and who saved themselves by flight.

When this terrible execution was over Schaibar came out of the council-hall into the midst of the courtyard with the iron bar upon his shoulder, and, looking hard at the grand vizier, who owed his life to Prince Ahmed, he said: “I know here is a certain magician, who is a greater enemy of my brother-in-law than all these base favorites I have chastised. Let the magician be brought to me presently.” The grand vizier immediately sent for her, and as soon as she was brought Schaibar said, at the time he fetched a stroke at her with his iron bar: “Take the reward of thy pernicious counsel, and learn to feign sickness again.”

After this he said: “This is not yet enough; I will use the whole town after the same manner if they do not immediately acknowledge Prince Ahmed, my brother-in-law, for their Sultan and the Sultan of the Indies.” Then all that were there present made the air echo again with the repeated acclamations of: “Long life to Sultan Ahmed”; and immediately after he was proclaimed through the whole town. Schaibar made him be clothed in the royal vestments, installed him on the throne, and after he had caused all to swear homage and fidelity to him went and fetched his sister Paribanou, whom he brought with all the pomp and grandeur imaginable, and made her to be owned Sultaness of the Indies.

As for Prince Ali and Princess Nouronnihar, as they had no hand in the conspiracy against Prince Ahmed and knew nothing of any, Prince Ahmed assigned them a considerable province, with its capital, where they spent the rest of their lives. Afterwards he sent an officer to Prince Houssain to acquaint him with the change and make him an offer of which province he liked best; but that Prince thought himself so happy in his solitude that he bade the officer return the Sultan his brother thanks for the kindness he designed him, assuring him of his submission; and that the only favor he desired of him was to give him leave to live retired in the place he had made choice of for his retreat.

Arabian Nights.

La storia del principe Ahmed e della fata Paribanou

C’era una volta un sultano che aveva tre figli e una nipote. Il più grande dei principi si chiamava Houssain, il secondo Alì, il più giovane Ahmed e la principessa, sua nipote, Nouronnihar.

La principessa Nouronnihar era la figlia del fratello minore del sultano, il quale era morto e aveva lasciato la principessa in tenera età. Il sultano si era fatto carico dell’educazione di sua figlia e l’aveva allevata a palazzo con i tre principi, proponendosi di farla sposare quando fosse arrivata all’età adatta e di contrarre allo scopo un’ alleanza con qualcuno dei principi vicini. Ma quando si accorse che i tre principi suoi figli l’amavano appassionatamente, pensò piuttosto seriamente a questa faccenda. Era molto preoccupato; la difficoltà che prevedeva era che si mettessero d’accordo e che i due fratelli minori acconsentissero a lasciarla al fratello maggiore. Siccome vide che erano molto ostinati, li mandò a chiamare tutti insieme e disse loro: “Figli miei, poiché per il vostro bene e la vostra tranquillità, non riesco a convincervi a non aspirare più alla principessa vostra cugina, penso non sarebbe fuori luogo se ognuno di voi viaggiasse per conto proprio in diversi paesi così da non poter incontrare gli altri. E siccome sapete che sono molto curioso e appassionato di qualsiasi cosa strana, prometto mia nipote in sposa a colui che mi porterà la rarità più straordinaria; e per l’acquisto della rarità di cui andrete in cerca e le spese di viaggio, darà a ciascuno una somma di denaro.”

Siccome i tre principi era sempre sottomessi e obbedienti al volere del sultano, e ciascuno si lusingava che la fortuna lo avrebbe favorito, acconsentirono tutti. Il sultano diede loro il denaro promesso e proprio quel giorno diedero gli ordini dei preparativi per i loro viaggi e presero congedo dal sultano per essere pronti a partire il mattino seguente. Di conseguenza tutti si diressero verso la medesima porta della città, ciascuno vestito come un mercante, seguito da un compagno di fiducia travestito da schiavo, e tutti in sella a bei cavalli e ben equipaggiati. Il primo giorno viaggiarono insieme e scesero in una locanda nel punto in cui la strada si divideva in tre diversi tratti. La notte, dopo che ebbero cenato insieme, concordarono di viaggiare per un anno e di incontrarsi alla locanda; il primo che fosse arrivato, avrebbe aspettato gli altri perché, siccome si erano congedati insieme dal sultano, insieme avrebbero fatto ritorno. Il mattino seguente all’alba, dopo essersi abbracciati e augurati buona fortuna a vicenda, montarono sui cavalli e ciascuno imboccò una strada diversa.

Il principe Houssain, il fratello maggiore, giunse a Bisnagar, capitale del regno che aveva quel nome e residenza del sovrano. Andò ad alloggiare in un caravanserraglio allestito per i mercanti stranieri; avendo appreso che c’erano quattro principali quartieri in cui mercanti di ogni genere vendevano le loro mercanzie e avevano le loro botteghe, in mezzo alle quali sorgeva il castello ossia il palazzo del re, andò il giorno seguente in uno di questi quartieri.

Il principe Houssain non poté che guardare con ammirazione questo quartiere. Era ampio e suddiviso da diverse strade, tutte coperte e riparate dal sole e tuttavia molto luminose. Vi erano botteghe di ogni genere e quelle che vendevano la medesima mercanzia erano in una sola strada, e la medesima cosa avveniva per gli artigiani, i quali avevano le loro botteghe nelle strade più piccole.

Il gran numero di botteghe, colme di ogni genere di mercanzia, come i lini più pregiati da varie parti dell’India, alcuni dipinti nei colori più vivaci e che rappresentavano animali, alberi e fiori; sete e broccati dalla Persia dalla Cina e da altri paesi; porcellane sia dalla Cina che dal Giappone, e arazzi che lo sorpresero tanto da non riuscire a credere ai propri occhi; ma quando giunse dai fabbri e dai gioiellieri fu estasiato nel vedere una tale prodigiosa quantità di oggetti d’oro e d’argento e fu abbagliato dallo splendore delle perle, dei diamanti, dei rubini, degli smeraldi e degli altri gioielli esposti in vendita.

Il principe Houssain ammirò particolarmente anche un’altra cosa ed era il gran numero di venditori di rose che affollava le strade perché gli indiani sono tanto appassionati di quel fiore che nessuno che non ne avesse un mazzo in mano o una ghirlanda sul capo e i mercanti le tenevano in vasi nelle loro botteghe così che l’aria ne era completamente profumata.

Dopo che il principe Houssain ebbe percorso questo quartiere strada per strada, i pensieri colmi delle ricchezze che aveva visto, si sentì molto stanco, e accorgendosi di ciò un mercante, lo invitò educatamente a sedere nella sua bottega e lui accettò; ma non rimase seduto a lungo prima di vedere un venditore ambulante che passava con un arazzo sul braccio, largo sei piedi, e gridava di venderlo a trenta borse (1). Il principe chiamò il venditore ambulante e gli chiese di vedere l’arazzo che gli sembrava essere valutato a un prezzo esorbitante, non solo per le sue dimensioni, ma per la scarsezza della sua qualità; quando l’ebbe esaminato bene, disse al venditore ambulante che non capiva come mai un arazzo così piccolo e dia spetto così insignificante potesse avere un prezzo così alto.

Il venditore ambulante, che l’aveva scambiato per un mercante, rise: “Se questo prezzo vi sembra così esorbitante, vi meraviglierete ancor di più quando vi dirò che ho avuto ordine di alzarlo a quaranta borse e di non separamene a meno.” Il principe rispose: “Di certo deve avere qualcosa di straordinario che io non so.”. “Avete indovinato, signore,” rispose il venditore ambulante “ e ne converrete quando sarete venuto a conoscenza del fatto che ovunque vi sediate su questo arazzo, potrete essere trasportato in un istante ovunque vogliate, senza essere fermato da nessun ostacolo.”

A queste parole del venditore ambulante il principe dell’India, in considerazione del fatto che il motivo principale per il quale stava viaggiando era portare a casa al sultano suo padre qualcosa di particolare rarità, pensò che non avrebbe potuto incontrare nessuno che gli desse maggior soddisfazione. “Disse al venditore ambulante: “Se l’arazzo ha la virtù che gli attribuisci, non penso che quaranta borse siano troppe, ma aggiunta ti farei un regalo. “Il venditore ambulante rispose: “Signore, ho detto la verità e mi sarà facile convincerci, appena avremo pattuito le quaranta borse a condizione di mostrarvi l’esperimento. Siccome suppongo che non abbiate con voi una tale somma e che per riceverla io debba venire con voi nel caravanserraglio in cui alloggiate, con il permesso del padrone del negozio andremo nel retrobottega e io stenderò l’arazzo; quando saremo seduti entrambi e voi avrete formulato il desiderio di essere trasportato nella vostra tende nel caravanserraglio, se non saremo trasportati là non concluderemo l’affare e voi sarete libero dall’impegno. Quanto al vostro regalo, sebbene io sia pagato dal venditore per il mio disturbo, lo riceverò come un favore e ve ne sarò molto obbligato e grato”

Sulla buonafede del venditore ambulante il principe accettò le condizioni e concluse l’affare; avendo ottenuto il permesso del padrone del negozio, andarono nel retrobottega; sedettero entrambi e appena il principe formulò il desiderio di essere trasportato nella sua tenda al caravanserraglio, si trovò subito là con il venditore ambulante; siccome non aveva bisogno di ulteriori prove della virtù dell’arazzo, contò quaranta borse per il venditore ambulante e gliene diede altre venti in dono.

In questo modo il principe Houssain diventò il proprietario dell’arazzo e fu molto contento che al proprio arrivo a Bisnagar avesse trovato un pezzo così raro che gli avrebbe guadagnato senza contese la mano di Nouronnihar. In breve pensava che sarebbe stato impossibile che i suoi fratelli venissero all’appuntamento con qualcosa di paragonabile all’arazzo. Grazie al suo potere, sedendovici sopra, avrebbe potuto trovarsi al luogo dell’appuntamento quel medesimo giorno, ma siccome sarebbe stato obbligato a rimanere lì in attesa dei fratelli, come avevano concordato, e siccome era curioso di vedere il re di Bisnagar e la sua corte e di apprendere la forza, le leggi, i costumi e la religione del regno, scelse di risiedere lì per un po’ e di trascorrere alcuni mesi soddisfacendo la propria curiosità.

Il principe Houssain avrebbe potuto trattenersi un po’ più a lungo nel regno e alla corte di Bisnagar, ma era così ansioso di stare più vicino alla principessa che, spiegando l’arazzo, lui e il compagno che aveva condotto con sé vi sedettero e appena egli ebbe formulato il desiderio, fu trasportato alla locanda nella quale lui e i suoi fratelli dovevano incontrarsi, e lì si fece passare per un mercante fino al loro arrivo.

Il principe Alì, secondo fratello del principe Houssain, che aveva deciso di viaggiare in Persia, prese la strada, essendosi unito a una carovana tre giorni dopo essersi separato dai fratelli, e dopo quattro giorni di viaggio giunse a Schiraz, che era la capitale del regno di Persia. Lì si fece passare per un gioielliere.

Il mattino seguente il principe Alì, che viaggiava solo per il proprio piacere e non aveva portato con se altro che lo stretto necessario, dopo essersi vestito, fece una passeggiata nella parte della città che a Schiraz era chiamata ‘il mercato all’aperto’.

Tra i vari venditori ambulanti che passavano avanti e indietro con diversi generi di mercanzie, offrendole in vendita, fu con non poca sorpresa che ne vide uno che portava in mano un cannocchiale d’avorio, lungo circa un piede e sottile come il pollice di un uomo, e gridava di venderlo per trenta borse. Dapprima pensò che il venditore ambulante fosse pazzo e per informarsi andò in una bottega e chiese al mercante, che stava sulla soglia: “Ve ne prego, signore, quell’uomo (indicando il venditore ambulante che offriva il cannocchiale d’avorio a trenta borse) è matto? Se non lo è, sono molto deluso.”

Il mercante rispose: “In verità, signore, era più sensato ieri; vi posso assicurare che sia uno dei abili venditori ambulanti che abbiamo e il più affidabile quando si tratta di vendere qualcosa di valore. E se per il cannocchiale d’avorio chiede a gran voce trenta borse, deve valere tanto o anche più in un modo o nell’altro. Verrà tra poco e glielo chiederemo, così sarete soddisfatto; nel frattempo sedete sul mio sofà e riposatevi.”

Il principe Alì accettò il cortese invito del mercante e poco dopo il venditore ambulante passò di lì. Il mercante lo chiamò per nome e, indicandogli il principe, gli disse: “Rispondi a quel gentiluomo, che mi ha chiesto se sei assennato quando intendi chiedere a gran voce trenta borse per il cannocchiale d’avorio, il quale non sembra valere tanto. Me ne stupirei io stesso, se non ti conoscessi.” Il venditore ambulante, rivolgendosi al principe Alì, disse: “Signore, non siete l’unica persona che mi prende per pazzo riguardo questo cannocchiale. Giudicherete voi stesso se lo sia o no quando vi avrò raccontato della sua caratteristica e spero vorrete valutarlo secondo questo alto prezzo come gli altri ai quali già l’ho mostrato e che avevano di me la vostra stessa cattiva opinione.”

Il venditore ambulante proseguì, presentando al principe il cannocchiale d’avorio: “Per prima cosa osservate che il tubo è dotato di vetri ad entrambe le estremità e considerate che , guardando attraverso una di esse, voi vedrete qualsiasi oggetto desideriate osservare.” Il principe disse: “Sono pronto a a farti le mie scuse per il discredito che ho gettato su di te se mi dimostrerai la verità di quanto sostieni.” e mentre teneva in mano il tubo d’avorio, dopo aver guardato i due vetri, disse: “Mostrami da quale estremità devo guardare per poter essere soddisfatto.” il venditore ambulante glielo mostrò e lui guardò attraverso, desiderando nel medesimo tempo vedere il sultano suo padre, che vide immediatamente in perfetta salute, seduto sul trono, nel bel mezzo di un consiglio di corte. Quindi, dato che dopo il sultano nessuno gli era più caro al mondo della principessa Nouronnihar, desiderò vederla; e la vide che rideva di ottimo umore mentre si acconciava, circondata dalle sue dame.

Il principe Alì non volle altre prove per essere persuaso che il cannocchiale fosse la cosa più preziosa del mondo e ritenne che se non l’avesse acquistato non avrebbe mai trovato di nuovo un’altra rarità simile. Quindi portò con sé il venditore ambulante nel caravanserraglio in cui alloggiava e gli contò le monete, ricevendo il cannocchiale.

Il principe Alì era molto contento del proprio affare e si convinse che, se i suoi fratelli non fossero stati in grado di trovare qualcosa di altrettanto raro e mirabile, la principessa Nouronnihar sarebbe stata la ricompensa della sua fatica e e delle sue tribolazioni; che oramai poteva pensare solo a visitare la corte di Persia in incognito e vedere qualsiasi cosa lo incuriosisse a Schiraz e dintorni finché la carovana con la quale era giunto facesse ritorno in India. Appena la carovana fu pronta, il principe si unì e, senza alcun incidente o fastidio al di là della durata del tragitto e della fatica del viaggio, arrivò felicemente nel luogo dell’appuntamento in cui trovò il principe Houssain ed entrambi attesero il principe Ahmed.

Il principe Ahmed, che aveva seguito la strada per Samarcanda, il giorno seguente all’arrivo là, come avevano fatto i suoi fratelli, era andato al ‘mercato all’aperto’ dove non aveva camminato a lungo prima di imbattersi in un venditore ambulante che teneva in mano una mela artificiale e la vendeva per trentacinque borse; perciò lo fermò e gli disse: “Fammi vedere la mela e dimmi quale virtù o straordinarie proprietà abbia per valere un prezzo così alto.” Mettendogliela in mano, il venditore ambulante disse. “Signore, se guardate l’aspetto esteriore di questa mela, è molto modesto, ma se considerate le sue proprietà, le sue virtù e i grandi utilità e benefici per il genere umano, vedrete che non ha prezzo e che chi la possieda sia il padrone di un grande tesoro. Per farla breve, cura tutte le persone malate delle malattie più mortali; se il paziente è moribondo, lo cura immediatamente e gli restituisce piena salute; e ciò si può fare nel modo più facile del mondo cioè facendola annusare al paziente.”

“Se devo crederti,” rispose il principe Ahmed “le virtù di questa mela sono meravigliose e ha un valore inestimabile, ma su che cosa mi posso basare, visto tutto cioò che mi hai detto, per essere certo della verità della faccenda?” Il venditore ambulante rispose: “Signore, la cosa è nota e riconosciuta in tutta la città di Samarcanda ma, senza ulteriore indugio, chiedete a tutti i mercanti che vedete e ascoltate ciò che dicono. Scoprirete che diversi di loro vi diranno che non avrebbero creduto di essere ancora vivi se non avessero usato questo eccellente rimedio. E per farvi comprendere meglio di cosa si tratti, vi devo dire che è il risultato dello studio e degli esperimenti di un celebre filosofo di questa città, il quale si è dedicato con tutto se stesso allo studio e alla conoscenza delle virtù delle piante e dei minerali, e alla fine ha ottenuto questo composto che in questa città ha operato guarigioni così sorprendenti che non saranno mai dimenticate, ma è morto improvvisamente prima di poter mettere in pratica il proprio rimedio sovrano e ha lasciato una moglie e un gran numero di figli piccoli dietro di sé in una situazione così precaria che la vedova ha deciso di vendere la mela per provvedere a se stessa e ai suoi bambini.”

Mentre il venditore ambulante informava il principe Ahmed delle virtù della mela artificiale, giunsero persone in gran numero le quali confermarono ciò che diceva; uno tra di loro disse di avere un amico mortalmente malato, la cui vita era appesa a un filo, e che era l’occasione favorevole per mostrare l’esperimento al principe Ahmed. A queste parole il principe disse al venditore ambulante che gli avrebbe dato quaranta borse se avesse curato quella persona malata.

Il venditore ambulante, che aveva l’ordine di venderla a quel prezzo, disse al principe Ahmed: “Venite, signore, andiamo a fare l’esperimento e la mela sarà vostra; posso assicurarvi che sortirà sempre gli effetti sperati. “ Per farla breve, l’esperimento ebbe successo e il principe, dopo aver contato quaranta borse per il venditore ambulante e aver ottenuto da lui la mela, attese pazientemente la prima carovana che facesse ritorno in India e arrivò in perfetta salute alla locanda in cui i principi Houssain e Alì lo stavano aspettando.