The King of the Waterfalls

(25'14'')

When the young king of Easaidh Ruadh came into his kingdom, the first thing he thought of was how he could amuse himself best. The sports that all his life had pleased him best suddenly seemed to have grown dull, and he wanted to do something he had never done before. At last his face brightened.

'I know!' he said. 'I will go and play a game with the Gruagach .' Now the Gruagach was a kind of wicked fairy, with long curly brown hair, and his house was not very far from the king's house.

But though the king was young and eager, he was also prudent, and his father had told him on his deathbed to be very careful in his dealings with the 'good people,' as the fairies were called. Therefore before going to the Gruagach the king sought out a wise man of the countryside.

'I am wanting to play a game with the curly-haired Gruagach,' said he.

'Are you, indeed?' replied the wizard. 'If you will take my counsel, you will play with someone else.'

'No; I will play with the Gruagach,' persisted the king.

'Well, if you must, you must, I suppose,' answered the wizard; 'but if you win that game, ask as a prize the ugly crop-headed girl that stands behind the door.'

'I will,' said the king.

So before the sun rose he got up and went to the house of the Gruagach, who was sitting outside.

'O king, what has brought you here to-day?' asked the Gruagach. 'But right welcome you are, and more welcome will you be still if you will play a game with me.'

'That is just what I want,' said the king, and they played; and sometimes it seemed as if one would win, and sometimes the other, but in the end it was the king who was the winner.

'And what is the prize that you will choose?' inquired the Gruagach.

'The ugly crop-headed girl that stands behind the door,' replied the king.

'Why, there are twenty others in the house, and each fairer than she!' exclaimed the Gruagach.

'Fairer they may be, but it is she whom I wish for my wife, and none other,' and the Gruagach saw that the king's mind was set upon her, so he entered his house, and bade all the maidens in it come out one by one, and pass before the king.

One by one they came; tall and short, dark and fair, plump and thin, and each said 'I am she whom you want. You will be foolish indeed if you do not take me.'

But he took none of them, neither short nor tall, dark nor fair, plump nor thin, till at the last the crop-headed girl came out.

'This is mine,' said the king, though she was so ugly that most men would have turned from her. 'We will be married at once, and I will carry you home.' And married they were, and they set forth across a meadow to the king's house. As they went, the bride stooped and picked a sprig of shamrock, which grew amongst the grass, and when she stood upright again her ugliness had all gone, and the most beautiful woman that ever was seen stood by the king's side.

The next day, before the sun rose, the king sprang from his bed, and told his wife he must have another game with the Gruagach.

'If my father loses that game, and you win it,' said she, 'accept nothing for your prize but the shaggy young horse with the stick saddle.'

'I will do that,' answered the king, and he went.

'Does your bride please you?' asked the Gruagach, who was standing at his own door. 'Ah! does she not!' answered the king quickly. 'Otherwise I should be hard indeed to please. But will you play a game to-day?'

'I will,' replied the Gruagach, and they played, and sometimes it seemed as if one would win, and sometimes the other, but in the end the king was the winner.

'What is the prize that you will choose?' asked the Gruagach.

'The shaggy young horse with the stick saddle,' answered the king, but he noticed that the Gruagach held his peace, and his brow was dark as he led out the horse from the stable. Rough was its mane and dull was its skin, but the king cared nothing for that, and throwing his leg over the stick saddle, rode away like the wind.

On the third morning the king got up as usual before dawn, and as soon as he had eaten food he prepared to go out, when his wife stopped him. 'I would rather,' she said, 'that you did not go to play with the Gruagach, for though twice you have won yet some day he will win, and then he will put trouble upon you.'

'Oh! I must have one more game,' cried the king; 'just this one.' And he went off to the house of the Gruagach.

Joy filled the heart of the Gruagach when he saw him coming, and without waiting to talk they played their game. Somehow or other, the king's strength and skill had departed from him, and soon the Gruagach was the victor.

'Choose your prize,' said the king, when the game was ended, 'but do not be too hard on me, or ask what I cannot give.'

'The prize I choose,' answered the Gruagach, 'is that the crop-headed creature should take thy head and thy neck, if thou dost not get for me the Sword of Light that hangs in the house of the king of the oak windows.'

'I will get it,' replied the young man bravely; but as soon as he was out of sight of the Gruagach he pretended no more, and his face grew dark and his steps lagging.

'You have brought nothing with you to-night,' said the queen, who was standing on the steps awaiting him. She was so beautiful that the king was fain to smile when he looked at her, but then he remembered what had happened, and his heart grew heavy again.

'What is it? What is the matter? Tell me thy sorrow that I may bear it with thee, or, it may be, help thee!' Then the king told her everything that had befallen him, and she stroked his hair the while.

'That is nothing to grieve about,' she said when the tale was finished. 'You have the best wife in Erin, and the best horse in Erin. Only do as I bid you, and all will go well.' And the king suffered himself to be comforted.

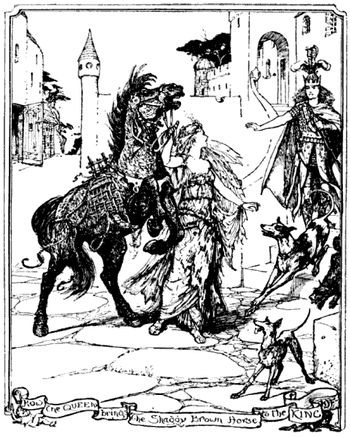

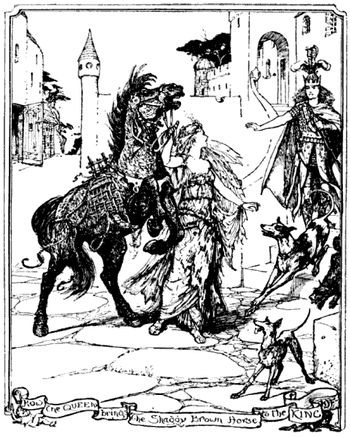

He was still sleeping when the queen rose and dressed herself, to make everything ready for her husband's journey; and the first place she went to was the stable, where she fed and watered the shaggy brown horse and put the saddle on it. Most people thought this saddle was of wood, and did not see the little sparkles of gold and silver that were hidden in it. She strapped it lightly on the horse's back, and then led it down before the house, where the king waited.

'Good luck to you, and victories in all your battles,' she said, as she kissed him before he mounted. 'I need not be telling you anything. Take the advice of the horse, and see you obey it.'

So he waved his hand and set out on his journey, and the wind was not swifter than the brown horse—no, not even the March wind which raced it and could not catch it. But the horse never stopped nor looked behind, till in the dark of the night he reached the castle of the king of the oak windows.

'We are at the end of the journey,' said the horse, 'and you will find the Sword of Light in the king's own chamber. If it comes to you without scrape or sound, the token is a good one. At this hour the king is eating his supper, and the room is empty, so none will see you. The sword has a knob at the end, and take heed that when you grasp it, you draw it softly out of its sheath. Now go! I will be under the window.'

Stealthily the young man crept along the passage, pausing now and then to make sure that no man was following him, and entered the king's chamber. A strange white line of light told him where the sword was, and crossing the room on tiptoe, he seized the knob, and drew it slowly out of the sheath. The king could hardly breathe with excitement lest it should make some noise, and bring all the people in the castle running to see what was the matter. But the sword slid swiftly and silently along the case till only the point was left touching it. Then a low sound was heard, as of the edge of a knife touching a silver plate, and the king was so startled that he nearly dropped the knob.

'Quick! quick!' cried the horse, and the king scrambled hastily through the small window, and leapt into the saddle.

'He has heard and he will follow,' said the horse; 'but we have a good start,' And on they sped, on and on, leaving the winds behind them.

At length the horse slackened its pace. 'Look and see who is behind you,' it said; and the young man looked.

'I see a swarm of brown horses racing madly after us,' he answered.

'We are swifter than those,' said the horse, and flew on again.

'Look again, O king! Is anyone coming now?' 'A swarm of black horses, and one has a white face, and on that horse a man is seated. He is the king of the oak windows.'

'That is my brother, and swifter still than I,' said the horse, 'and he will fly past me with a rush. Then you must have your sword ready, and take off the head of the man who sits on him, as he turns and looks at you. And there is no sword in the world that will cut off his head, save only that one.'

'I will do it,' replied the king; and he listened with all his might, till he judged that the white-faced horse was close to him. Then he sat up very straight and made ready. The next moment there was a rushing noise as of a mighty tempest, and the young man caught a glimpse of a face turned towards him. Almost blindly he struck, not knowing whether he had killed or only wounded the rider. But the head rolled off, and was caught in the brown horse's mouth.

'Jump on my brother, the black horse, and go home as fast as you can, and I will follow as quickly as I may,' cried the brown horse; and leaping forward the king alighted on the back of the black horse, but so near the tail that he almost fell off again. But he stretched out his arm and clutched wildly at the mane and pulled himself into the saddle.

Before the sky was streaked with red he was at home again, and the queen was sitting waiting till he arrived, for sleep was far from her eyes. Glad was she to see him enter, but she said little, only took her harp and sang softly the songs which he loved, till he went to bed, soothed and happy.

It was broad day when he woke, and he sprang up saying:

'Now I must go to the Gruagach, to find out if the spells he laid on me are loose.'

'Have a care,' answered the queen, 'for it is not with a smile as on the other days that he will greet you. Furiously he will meet you, and will ask you in his wrath if you have got the sword, and you will reply that you have got it. Next he will want to know how you got it, and to this you must say that but for the knob you had not got it at all. Then he will raise his head to look at the knob, and you must stab him in the mole which is on the right side of his neck; but take heed, for if you miss the mole with the point of the sword, then my death and your death are certain. He is brother to the king of the oak windows, and sure will he be that the king must be head, or the sword would not be in your hands.' After that she kissed him, and bade him good speed.

'Didst thou get the sword?' asked the Gruagach, when they met in the usual place. 'I got the sword.' 'And how didst thou get it?' 'If it had not had a knob on the top, then I had not got it,' answered the king.

'Give me the sword to look at,' said the Gruagach, peering forward; but like a flash the king had drawn it from under his nose and pierced the mole, so that the Gruagach rolled over on the ground.

'Now I shall be at peace,' thought the king. But he was wrong, for when he reached home he found his servants tied together back to back with cloths bound round their mouths, so that they could not speak. He hastened to set them free, and he asked who had treated them in so evil a manner.

'No sooner had you gone than a great giant came, and dealt with us as you see, and carried off your wife and your two horses,' said the men.

'Then my eyes will not close nor will my head lay itself down till I fetch my wife and horses home again,' answered he, and he stopped and noted the tracks of the horses on the grass, and followed after them till he arrived at the wood, when the darkness fell.

'I will sleep here,' he said to himself, 'but first I will make a fire,' And he gathered together some twigs that were lying about, and then took two dry sticks and rubbed them together till the fire came, and he sat by it.

The twigs cracked and the flame blazed up, and a slim yellow dog pushed through the bushes and laid his head on the king's knee, and the king stroked his head. 'Wuf, wuf,' said the dog. 'Sore was the plight of thy wife and thy horses when the giant drove them last night through the forest.' 'That is why I have come,' answered the king; and suddenly his heart seemed to fail him and he felt that he could not go on. 'I cannot fight that giant,' he cried, looking at the dog with a white face. 'I am afraid, let me turn homewards.'

'No, don't do that,' replied the dog. 'Eat and sleep, and I will watch over you.' So the king ate and lay down, and slept till the sun waked him.

'It is time for you to start on your way,' said the dog, 'and if danger presses, call on me, and I will help you.'

'Farewell, then,' answered the king; 'I will not forget that promise,' and on he went, and on, and on, till he reached a tall cliff with many sticks lying about.

'It is almost night,' he thought; 'I will make a fire and rest,' and thus he did, and when the flames blazed up, the hoary hawk of the grey rock flew on to a bough above him.

'Sore was the plight of thy wife and thy horses when they passed here with the giant,' said the hawk.

'Never shall I find them,' answered the king, 'and nothing shall I get for all my trouble.'

'Oh, take heart,' replied the hawk; 'things are never so bad but what they might be worse. Eat and sleep and I will watch thee,' and the king did as he was bidden by the hawk, and by the morning he felt brave again.

'Farewell,' said the bird, 'and if danger presses call to me, and I will help you.'

On he walked, and on and on, till as dusk was falling he came to a great river, and on the bank there were sticks lying about. 'I will make myself a fire,' he thought, and thus he did, and by and bye a smooth brown head peered at him from the water, and a long body followed it.

'Sore was the plight of thy wife and thy horses when they passed the river last night,' said the otter. 'I have sought them and not found them,' answered the king, 'and nought shall I get for my trouble.'

'Be not so downcast,' replied the otter; 'before noon to-morrow thou shalt behold thy wife. But eat and sleep and I will watch over thee.' So the king did as the otter bid him, and when the sun rose he woke and saw the otter lying on the bank.

'Farewell,' cried the otter as he jumped into the water, 'and if danger presses, call to me and I will help you.' For many hours the king walked, and at length he reached a high rock, which was rent into two by a great earthquake. Throwing himself on the ground he looked over the side, and right at the very bottom he saw his wife and his horses. His heart gave a great bound, and all his fears left him, but he was forced to be patient, for the sides of the rock were smooth, and not even a goat could find foothold. So he got up again, and made his way round through the wood, pushing by trees, scrambling over rocks, wading through streams, till at last he was on flat ground again, close to the mouth of the cavern.

His wife gave a shriek of joy when he came in, and then burst into tears, for she was tired and very frightened. But her husband did not understand why she wept, and he was tired and bruised from his climb, and a little cross too.

'You give me but a sorry welcome,' grumbled he, 'when I have half-killed myself to get to you.' 'Do not heed him,' said the horses to the weeping woman; 'put him in front of us, where he will be safe, and give him food, for he is weary.' And she did as the horses told her, and he ate and rested, till by and bye a long shadow fell over them, and their hearts beat with fear, for they knew that the giant was coming.

'I smell a stranger,' cried the giant, as he entered; but it was dark inside the chasm, and he did not see the king, who was crouching down between the feet of the horses.

'A stranger, my lord! no stranger ever comes here, not even the sun!' and the king's wife laughed gaily as she went up to the giant and stroked the huge hand which hung down by his side. 'Well, I perceive nothing, certainly,' answered he, 'but it is very odd. However, it is time that the horses were fed;' and he lifted down an armful of hay from a shelf of rock and held out a handful to each animal, who moved forward to meet him, leaving the king behind. As soon as the giant's hands were near their mouths they each made a snap, and began to bit them, so that his groans and shrieks might have been heard a mile off. Then they wheeled round and kicked him till they could kick no more. At length the giant crawled away, and lay quivering in a corner, and the queen went up to him.

'Poor thing! poor thing!' she said, 'they seem to have gone mad; it was awful to behold.'

'If I had had my soul in my body they would certainly have killed me,' groaned the giant. 'It was lucky indeed,' answered the queen; 'but tell me, where is thy soul, that I may take care of it?'

'Up there, in the Bonnach stone,' answered the giant, pointing to a stone which was balanced loosely on an edge of rock. 'But now leave me, that I may sleep, for I have far to go to-morrow.'

Soon snores were heard from the corner where the giant lay, and then the queen lay down too, and the horses, and the king was hidden between them, so that none could see him.

Before the dawn the giant rose and went out, and immediately the queen ran up to the Bonnach stone, and tugged and pushed at it till it was quite steady on its ledge, and could not fall over. And so it was in the evening when the giant came home; and when they saw his shadow, the king crept down in front of the horses.

'Why, what have you done to the Bonnach stone?' asked the giant.

'I feared lest it should fall over, and be broken, with your soul in it,' said the queen, 'so I put it further back on the ledge.'

'It is not there that my soul is,' answered he, 'it is on the threshold. But it is time the horses were fed;' and he fetched the hay, and gave it to them, and they bit and kicked him as before, till he lay half dead on the ground.

Next morning he rose and went out, and the queen ran to the threshold of the cave, and washed the stones, and pulled up some moss and little flowers that were hidden in the crannies, and by and bye when dusk had fallen the giant came home.

'You have been cleaning the threshold,' said he.

'And was I not right to do it, seeing that your soul is in it?' asked the queen.

'It is not there that my soul is,' answered the giant. 'Under the threshold is a stone, and under the stone is a sheep, and in the sheep's body is a duck, and in the duck is an egg, and in the egg is my soul. But it is late, and I must feed the horses;' and he brought them the hay, but they only bit and kicked him as before, and if his soul had been within him, they would have killed him outright.

It was still dark when the giant got up and went his way, and then the king and the queen ran forward to take up the threshold, while the horses looked on. But sure enough! just as the giant had said, underneath the threshold was the flagstone, and they pulled and tugged till the stone gave way. Then something jumped out so suddenly, that it nearly knocked them down, and as it fled past, they saw it was a sheep.

'If the slim yellow dog of the greenwood were only here, he would soon have that sheep,' cried the king; and as he spoke, the slim yellow dog appeared from the forest, with the sheep in his mouth. With a blow from the king, the sheep fell dead, and they opened its body, only to be blinded by a rush of wings as the duck flew past.

'If the hoary hawk of the rock were only here, he would soon have that duck,' cried the king; and as he spoke the hoary hawk was seen hovering above them, with the duck in his mouth. They cut off the duck's head with a swing of the king's sword, and took the egg out of its body, but in his triumph the king held it carelessly, and it slipped from his hand, and rolled swiftly down the hill right into the river.

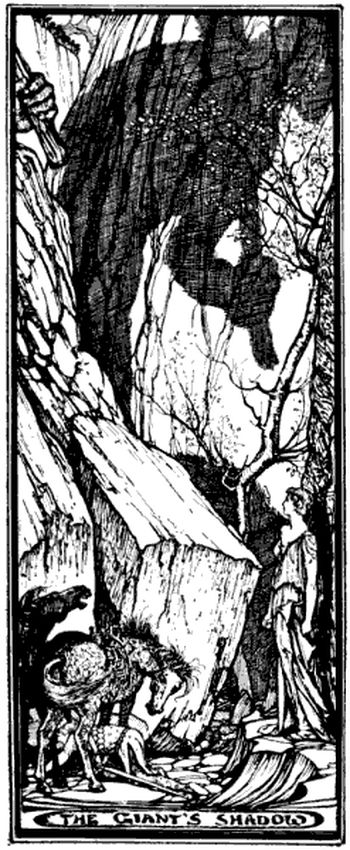

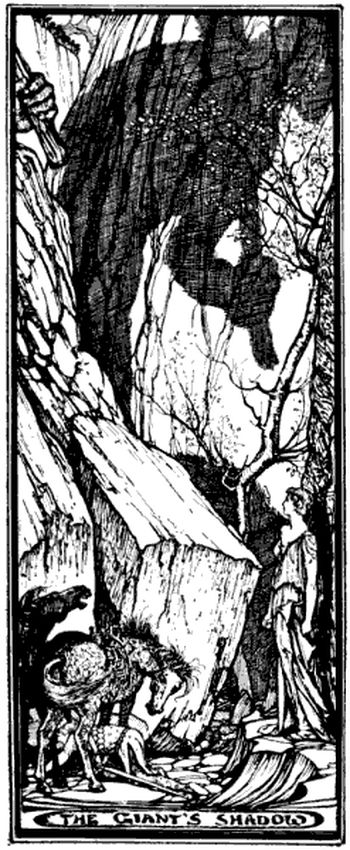

'If the brown otter of the stream were only here, he would soon have that egg,' cried the king; and the next minute there was the brown otter, dripping with water, holding the egg in his mouth. But beside the brown otter, a huge shadow came stealing along—the shadow of the giant.

The king stood staring at it, as if he were turned into stone, but the queen snatched the egg from the otter and crushed it between her two hands. And after that the shadow suddenly shrank and was still, and they knew that the giant was dead, because they had found his soul.

Next day they mounted the two horses and rode home again, visiting their friends the brown otter and the hoary hawk and the slim yellow dog by the way.

From 'West Highland Tales.'

Il re delle cascate

Quando il giovane re di Easaidh Ruadh entrò nel proprio regno, per prima cosa pensò a come avrebbe potuto divertirsi nel miglior modo. Gli sporto che gli erano piaciuti tutta la vita all’improvviso gli erano venuti a noia e voleva fare qualcosa che non avesse mai fatto prima. Alla fine il suo volto si illuminò.

”Ho trovato!” disse, “andrò a fare una partita con il Gruagach (1).” Dovete sapere che il Gruagach era una sorta di creatura malvagia dai lunghi riccioli bruni e la cui casa non era molto lontana da quella del re.

Sebbene il re fosse giovane e impaziente, era anche prudente, e suo padre sul letto di morte gli aveva detto di stare molto attento nei suoi rapporti con il ’buon popolo’, come erano chiamati gli esseri fatati. Perciò prima di andare dal Gruagach il re andò in cerca di un uomo saggio del paese.

”Sto andando a fare una partita con il ricciuto Gruagach,” disse.

”Veramente?” rispose il mago. “Se vuoi il mio consiglio, gioca con chiunque altro.”

”No, giocherò con il Gruagach.” insistette il re.

”Ebbene, se lo devi fare, devi, suppongo,” rispose il mago, “ma se vincerai la gara, chiedi come premio la brutta ragazza rapata che sta dietro la porta.”

”Lo farò.” disse il re.

Così prima che sorgesse il sole si alzò e andò a casa del Gruagach, il quale era seduto fuori.

”O re, che cosa ti ha cpndotto qui oggi?” disse il Gruagach. “Sei il benvenuto e lo sarai ancora di più se vorrai fare una partita con me.”

”È proprio ciò che voglio,” disse il re, e giocarono; a volte sembrava che vincesse l’uno, a volte l’altro, ma alla fine fu il re a vincere.

”Quale premio sceglierai?” chiese il Gruagach.

”La brutta ragazza rapata che sta dietro la porta.” rispose il re.

”Perché? Ce ne sono altre venti in casa, e ognuna più bella di lei!” esclamò il Gruagach.

”Saranno anche più belle, ma è lei che voglio come moglie, nessun’altra.” Il Gruagach vide che il re si era fissato con lei, così entrò in casa e ordinò alle ragazze di uscire a una a una e di sfilare davanti al re.

Vennero a una a una; alte e basse, more e bionde, grassottelle e magre, e ciascuna disse ‘Sono io quella che vuoi. Devi essere pazzo se non mi scegli.’

Ma egli non si curò di loro, né di quella bassa e né di quella alta, né mora né bionda, grassottella o magra, finché alla fine uscì la ragazza rapata.

”Questa è mia.” Disse il re, sebbene fossi così brutta che la maggior parte degli uomini avrebbe distolto il viso da lei. “Ci sposeremo subito e la porterò a casa con me.” Si sposarono e poi si avviarono per un prato verso la casa del re. Come vi giunsero, la sposa si fermò e raccolse un trifoglio che cresceva in mezzo all’erba, e quando si sollevò tutta la sua bruttezza era svanita, e a fianco del re c’era la più splendida donna che si fosse mai vista.

Il mattino dopo, prima che sorgesse il sole, il re saltò fuori dal letto e disse a sua moglie di voler fare un’altra partita con il Gruanach.

“Se mio padre perderà la partita e vincerai tu,” disse lei, “non accettare in premio niente altro che il puledro dal pelo ispido con la sella di legno.

Lo farò.” rispose il re e se ne andò.

”Ti piace la tua sposa?” chiese il Gruagach, che stava fuori della porta.

”No davvero!” rispose senza esitazione il re. “D0’altronde sarebbe difficile che piacesse. Oggi giocherai?”

”Lo farò.” rispose il Gruanach, e giocarono; a volte sembrava che vincesse l’uno, a volte l’altro, ma alla fine fu il vincitore fu il re.

”Quale premio sceglierai?” chiese il Gruagach.

”Il puledro dal pelo ispido con la sella di legno.” rispose il re, ma si accorse che il Gruagach taceva e la sua fronte era aggrottata mentre portava fuori dalla stalla il cavallo. La sua criniera era ruvida e il pelo opaco, ma al re non interessava nulla e montando sulla sella di legno, cavalcò via veloce come il vento.

La terza mattina il re si alzò prima dell’alba come il solito e, appena mangiato, si preparava ad uscire quando sua moglie lo trattenne e disse: “Preferirei di gran lunga che non andassi a giocare con il Gruagach perché sebbene tu abbia vinto due volte, una volta o l’altra vincerà lui e allora ti metterà nei guai.”

”Oh, devo giocare ancora una volta,” gridò il re, “solo questa.” e andò a casa del Gruagach.

Il cuore del Gruagach si colmò di gioia quando lo vide tornare e, senza spettare che parlasse, cominciarono la partita. In un modo o nell’altro la forza e l’abilità abbandonarono il re e ben presto il Gruagach vinse.

”Scegli il tuo premio,” disse il re, quando la partita fu terminata, “ma fa che non sia troppo per me e non chiedermi ciò che non posso darti.”

Il Gruagach rispose: “Il premio che scelgo è che la creatura rapata ti separi la testa dal collo se non prenderai per me la Spada di Luce nella casa del re delle finestre di quercia.”

”La prenderò.” Rispose coraggiosamente il giovane; ma appena non fu più visibile al Gruagach, non seppe più fingere e il suo volto si fece scuro e i suoi passi trascinati.

”Stanotte non hai portato niente con te,” disse la regina, che era rimasta alzata ad aspettarlo. Era così bella che il re fu pronto a sorridere nel guardarla, ma poi rammentò ciò che era accaduto e il suo cuore si fece di nuovo pesante.

”Che c’è? Che cosa è successo? Confidami il tuo dispiacere affinché io possa sopportarlo con te, o aiutarti, se sarà possibile!” allora il re le raccontò tutto ciò che gli era accaduto e intanto gli accarezzava i capelli.

”Non c’è motivo per affliggersi,” disse quando il racconto fu terminato. “Hai la miglior moglie e il miglior cavallo d’Irlanda. Fai ciò che ti dico e tutto andrà bene.” E il re si lasciò confortare.

Stava ancora dormendo quando la regina si alzò e si vestì, per far sì che tutto fosse pronto per il viaggio del marito; prima andò nella stalla dove nutrì e abbeverò l’ispido cavallo marrone e lo sellò. La maggior parte delle persone avrebbe pensato che questa sella fosse di legno, senza vedere le pagliuzze d’oro e d’argento che vi erano celate. La assicurò con delicatezza sul dorso del cavallo e poi lo condusse verso casa, dove il re stava aspettando.

”Buona fortuna a te, e vinci tutte le battaglie,” disse lei, e lo baciò prima che montasse in sella. “Non occorre che ti dica altro. Segui i consigli del cavallo e obbedisci.”

Così la salutò con la mano e iniziò il viaggio, il vento non era più veloce del cavallo marrone, no, neppure il vento di marzo che gareggiava a con lui e non poteva raggiungerlo. Il cavallo non si fermò mai e non si volse indietro finché, nel cuore della notte, raggiunse il castello del re delle finestre di quercia.

”Siamo giunti alla fine del viaggio,” disse il cavallo, “e troverai la Spada di Luce nella camera del re. Se la porterai con te senza che rumore o suono, sarà buon segno. A quest’ora il re sta cenando e la stanza è vuota, così nessuno ti vedrà. La spada ha un’impugnatura all’estremità, tienine conto quando l’afferrerai, così la estrarrai delicatamente dal fodero. Ora va’! Io sarò sotto la finestra.

Il giovane scivolò furtivamente attraverso il passaggio, fermandosi di tanto in tanto per essere sicuro che nessuno lo stesse seguendo, ed entrò nella camera del re. Una strana lama di luce bianca gli disse dove si trovasse la spada e, attraversando la stanza in punta di piedi, scorse l’impugnatura ed estrasse lentamente la spada dal fodero. Il re respirava appena per paura di fare rumore e di far accorrere tutta la gente del castello a vedere che cosa succedesse. Ma la spada scivolò dolcemente e silenziosamente lungo il fodero finché lo sfiorò in un solo punto. Allora si sentì un suono cupo, come di un coltello che sfiorasse un piatto d’argento, e il re fu così sorpreso che quasi lasciò cadere l’impugnatura.

”Presto! Presto!” gridò il cavallo, e il re scavalcò in fretta la finestrella e saltò sulla sella.

”Ti ha sentito e ci inseguirà,” disse il cavallo, “ma abbiamo un buon vantaggio.” e accelerarono, senza sosta, lasciandosi il vento alle spalle.

Finalmente il cavallo rallentò l’andatura. “Guarda chi c’è dietro di te.” disse, e il giovane guardò.

”Vedo un branco di cavalla marroni che corrono freneticamente dietro di noi.” rispose.

”Siamo più veloci di loro.” disse il cavallo e si slanciò di nuovo.

”Guarda di nuovo, maestà! Sta arrivando qualcuno?”

”Un branco di cavalli neri e uno ha il muso bianco, e su quel cavallo c’è in sella un uomo. È il re delle finestre di quercia.”

”Quello è mio fratello ed è più veloce di me,” disse il cavallo, “mi sorpasserà in un soffio. Tieni pronta la spada e taglia la testa dell’uomo che lo cavalca, quando si gira e ti guarda. Non c’è spada al mondo salvo questa che possa tagliargliela.”

”Lo faro,” rispose il re; e ascoltò con la massima attenzione finché ritenne che il cavallo dal muso bianco fosse vicino. Allora raddrizzò la schiena e si tenne pronto. Un momento dopo ci fu un rapido rumore come di una potente tempesta e il giovane scorse un viso rivolto verso di lui. Colpì piuttosto alla cieca, senza sapere se avesse ucciso o solamente ferito il cavaliere. Ma la testa rotolò e fu afferrata dalla bocca del cavallo marrone.

”Salta in groppa a mio fratello, il cavallo nero, e corri a casa più in fretta che puoi, io ti seguirò più in fretta che potrò.” gridò il cavallo marrone; e balzando avanti il re atterrò sul dorso del cavallo nero, ma così vicino alla coda che quasi cadde. Allora allungò le braccia e si afferrò saldamente alla criniera, rimettendosi in sella.

Prima che albeggiasse fu di nuovo a casa e la regina era seduta ad aspettare che arrivasse, perché dormire era l’ultimo dei suoi pensieri. Felice di vederlo entrare, parlò appena e prese l’arpa, cantando dolcemente le canzoni che lui amava finché andò a letto calmo e felice.

Era pieno giorno quando si svegliò e balzò su, dicendo:

”Ora devo andare dal Gruagach per scoprire se gli incantesimi che mi ha lanciato sono sciolti.”

”Fa’ attenzione,” disse la regina, “ perché non ti accoglierà con un sorriso come nei giorni passati. Ti verrà incontro furibondo e ti chiederà in collera se hai portato la spada, allora tu rispondigli che l’hai fatto. Poi vorrà sapere come ci sei riuscito e a questo punto devi dirgli che ci sei riuscito solo grazie all’impugnatura. Allora lui solleverà la testa per guardarla e tu devi conficcargliela nel neo che ha sul lato destro del collo. Bada bene, perché se manchi il neo con la punta della spada, allora la mia morte e la tua saranno certe. Lui è il fratello del re delle finestre di quercia e di sicuro sa che il re è stato decapitato, o la spada non potrebbe essere nelle tue mani.” Dopodiché lo baciò e gli augurò buona fortuna.

”Hai preso la spada?” chiese il Gruagach quando s’incontrarono al solito posto.

”Ce l’ho”

”E come l’hai presa?”

”Se no avesse avuto all’estremità un’impugnatura, non avrei potuto prenderla.” rispose il re.

”Dammi la spada perché possa guardarla.” disse il Gruagach, sbirciando davanti; veloce come un lampo il re gliela tolse da sotto il naso e trapassò il neo, cosicché il Gruagach rotolò a terra.

”Ora staremo in pace.” pensò il re, ma si sbagliava perché, quando fu giunto a casa, trovò i servi legati dorso a dorso e con un bavaglio sulla bocca affinché non potessero parlare. Si affrettò a liberarli e chiese chi li avesse trattati in modo tanto malvagio.

”Ve n’eravate appena andato quando è arrivato un gigante e ci ha sistemati come avete visto, poi ha portato via vostra moglie e i vostri due cavalli.” dissero gli uomini.

”Che gli occhi non mi si chiudano e la testa non si posi finché non avrò riportato a casa mia moglie e i cavalli.” rispose, e si fermò a osservare le tracce dei cavalli nell’erba, seguendole finché giunse nella foresta al calar delle tenebre.

”Dormirò qui,” si disse, “ma prima accenderò un fuoco.” Raccolse un po’ di rametti che stavano lì attorno , poi prese due bastoncini secchi e li strofinò l’uno contro l’altro finché presero fuoco, poi si sedette lì accanto.

I rametti crepitavano e la fiamma divampò; un cane magro e giallo sbucò dai cespugli e appoggiò la testa sulle ginocchia del re e lui gli strofinò la testa. “Bau, bau,” fece il cane. “Triste la sorte di tua moglie e dei tuoi cavalli quando il gigante la scorsa notte li ha condotti per la foresta.”

”Ecco perché devo andare.” rispose il re; improvvisamente il cuore sembrò venirgli meno e sentì che non sarebbe riuscito ad andare avanti.

”Non posso combattere quel gigante,” gridò, fissando il cane con volto pallido. “Ho paura, lasciami tornare indietro.”

”No, non farlo,” rispose il cane. “Magia e dormi, io veglierò su di te.” Così il re mangiò e si sdraiò, dormendo finché il sole lo svegliò.

”È tempo che tu riprenda il cammino,” disse il cane, “e se il pericolo ti minaccia, chiamami, ti aiuterò.”

”Addio, dunque,” rispose il re, “non dimenticherò questa promessa.” e se ne andò, avanti e avanti, finché raggiunse un’alta scogliera con numerosi rami sparsi qua e là.

”È quasi notte,” pensò, “accenderò un fuoco e mi riposerò.” E così fece; quando la fiamma divampò, il venerabile falco della roccia grigia si posò su un ramo vicino a lui.

”Triste la sorte di tua moglie e dei tuoi cavalla quando sono passati di qui con il gigante.” Disse il falco.

”Non li troverò mai,” rispose il re, “E non potrò far nulla per tutte le mie tribolazioni.”

Il falco rispose: “Oh, fatti forza, le cose non stanno così male, ma potrebbero peggiorare. Mangia e dormi e io veglierò su di te.” Il re fece come gli aveva detto il falco e il mattino seguente si sentì di nuovo coraggioso.

”Addio,” disse l’uccello, “e se il pericolo ti minaccia, io ti aiuterò.”

Il re proseguì, oltre e ancora oltre, finché al crepuscolo giunse presso un grande fiume, sulle cui rive c’erano molti ramoscelli.

”Accenderò un bel fuoco,” pensò, e così fece, e di lì a poco una liscia testa marrone lo sbirciò dall’acqua, seguita da un lungo corpo.

”Triste la sorte di tua moglie e dei tuoi cavalla quando hanno attraversato il fiume la scorsa notte.” disse la lontra.

”Li ho cercati e non li ho trovati,” rispose il re, “ e non c’è nulla che possa fare per le mie pene.”

”Non abbatterti così,” rispose la lontra, “prima che venga il mezzogiorno di domani vedrai tua moglie. Mangia e dormi, io veglierò su di te.” Il re fece come gli aveva detto la lontra; quando sorse il sole si svegliò e vide la lontra sulla riva.

”Addio,” gridò la lontra saltando nell’acqua, “se il pericolo ti minaccerà, chiamami e ti aiuterò.”

Il re camminò per molte ore e infine giunse ad un’alta roccia, che si era spaccata in due per un grande terremoto. Gettandosi per terra, guardò dall’altra parte e proprio in fondo vide sua moglie e i cavalli. Il suo cuore fece un gran balzo e la paura lo abbandonò, ma doveva avere pazienza perché i fianchi della roccia erano lisci e nemmeno una capra avrebbe trovato un appiglio. Così si rialzò e si fece strada attraverso la foresta, spingendosi tra gli alberi, arrampicandosi sulle rocce, guadando le correnti, finché alla fine fu di nuovo sul terreno, accanto all’imboccatura della caverna.

Sua moglie lanciò un grido di gioia quando entrò, poi scoppiò in lacrime perché era sfinita e assai spaventata. Suo marito non capiva perché piangesse, era stanco e malconcio per l’arrampicata e anche un po’ arrabbiato.

”Mi dai uno sgradevole benvenuto,” borbottò, “quando sono mezzo morto per raggiungerti.”

”Non dargli retta,” disse il cavallo alla donna in lacrime, “mettilo di fronte a noi, dive sarà al sicuro, e dagli del cibo perché è affaticato.” Lei fece come aveva detto il cavallo, lui mangiò e si riposò finché una lunga ombra li coprì e i loro cuori batterono impauriti perché sapevano che il gigante stava arrivando.

”Sento odore di straniero,” gridò il gigante mentre entrava; ma era buio all’interno della cavità e non vide il re, che si era accucciato tra le zampe dei cavalli.

”Uno straniero, mio signore! Nessuno straniero è mai entrato qui, nemmeno il sole!” e la moglie del re rise allegramente mentre si avvicinava al gigante e accarezzava la grande mano che pendeva lungo il suo fianco.

”Beh, non vedo nulla, certamente,” rispose, “ ma è molto strano. In ogni modo è ora che i cavalli siano nutriti.” e tirò giù da una sporgenza di roccia una bracciata di fieno e ne diede una manciata a ciascun animale, che si mosse verso di lui, lasciando indietro il re. Appena le mani del gigante furono vicino alle loro bocche, ciascuno la chiuse di scatto e cominciarono a morderle, tanto che i suoi lamenti e le sue urla di sarebbero potute sentire per miglia. Allora si voltarono improvvisamente e lo presero a calci finché non ne poterono più. Alla fine il gigante si trascinò via e si acquattò tremante in un angolo; la regina si levò su di lui.

”Poverino! Poverino!” disse. “Sembra ti abbiano conciato male; è orribile a vedersi.”

”Se avessi avuto l’anima in corpo, mi avrebbero ucciso certamente.” Gemette il gigante.

”Davvero una bella fortuna,” rispose la regina; “Dimmi, dov’è la tua anima, cisì che io possa avere cura di lei?”

”Lassù, nella pietra di Bonnach,” rispose il gigante, indicando una pietra in bilico sul bordo di una roccia. “Adesso lasciami, così che io possa dormire perché domani devo andare lontano.”

Ben presto si sentì russare dall’angolo in cui era sdraiato il gigante e allora anche la regina si sdraiò, e i cavalli, e il re era nascosto tra di loro così che nessuno avrebbe potuto vederlo.

Prima dell’alba il gigante si alzò e uscì, e subito la regina corse alla pietra di Bonnach e la tirò e la spinse finché fu quasi ferma sulla sporgenza e non sarebbe potuta cadere. E fu così che era sera, quando il gigante tornò a casa; quando videro la sua ombra, il re sgattaiolò sotto i cavalli.

”Che cosa hai fatto alla pietra di Bonnach?” chiese il gigante.

”Avevo paura che potesse cadere e rompersi, con dentro la tua anima,” disse la regina, “così l’ho spostata più indietro sulla sporgenza.”

”Non è lì dentro che c’è la mia anima,” rispose lui, “è sulla soglia. Adesso è ora di dar da magiare ai cavalli.” e andò a prendere il fieno, lo diede loro ed essi lo morsero e lo presero a calci come la volta precedente, lasciandolo mezzo morto per terra.

La mattina seguente si alzò e uscì, la regina corse verso la soglia della caverna e lavò la pietra, la adornò di muschio e di fiorellini che erano cresciuti in una crepa, e presto, quando scesce l’imbrunire, il gigante tornò a casa.

”Hai pulito la soglia.” disse.

”E non era giusto farlo, visto che la tua anima si trova lì?” disse la regina.

”La mia anima non è lì,” rispose il gigante. “Sotto la soglia c’è una pietra, sotto la pietra c’è una pecora, nel corpo della pecora c’è un’anatra, nell’anatra c’è un uovo e nell’uovo c’è la mia anima. Ma è tardi e devo dar da mangiare ai cavalli.” E portò loro il fieno, ma lo morsero e lo calciarono come la volta precedente, cosicché se l’anima fosse stata in lui, l’avrebbero ucciso del tutto.

Era ancora buio quando il gigante si alzò e andò per la propria strada, allora il re ela regina corsero a sollevare la soglia mentre i cavalli guardavano. In effetti, proprio come aveva detto il gigante, sotto la soglia c’era una pietra da lastrico, e loro due tirarono e strattonarono finché venne via. Qualcosa balzò fuori improvvisamente e quasi li colpì, e come scappò oltre, videro che era una pecora.

”Se solo il magro cane giallo del bosco fosse qui, prenderebbe subito la pecora.” Gridò il re. Aveva appena parlato che dalla foresta comparve il cane giallo e magro con la pecora in bocca. Al primo colpo del re, la pecora cadde morta, e aprirono il suo corpo per essere quasi accecati da un frullo d’ali mentre l’anatra volava via veloce.

”Se solo il venerabile falco della roccia fosse qui, prenderebbe subito l’anatra.” Gridò il re; aveva appena parlato che videro librarsi su loro il falco con l’anatra nel becco. Tagliarono la testa dell’anatra con un colpo della spada del re e presero l’uovo nel suo corpo, ma nell’esultanza del momento il re lo afferrò in modo maldestro e gli scivolò di mano, rotolando per la collina verso il fiume.

”Se solo la marmotta marrone della corrente fosse qui, prenderebbe subito l’uovo.” gridò il re; un minuto dopo c’era la marmotta marrone che, uscita gocciolante dall’acqua, teneva in bocca l’uovo. Ma dietro la marmotta marrone si levò una grossa ombra, l’ombra del gigante.

Il re rimase a fissarlo, come se si fosse tramutato in pietra, ma la regina prese l’uovo alla lontra e lo schiacciò tra le mani. Poco dopo l’ombra improvvisamente si rattrappì e sparì, così seppero che il gigante era morto perché avevano trovato la sua anima.

Il giorno seguente montarono sui cavalli e galopparono verso casa, facendo visita lungo la strada ai loro amici la marmotta marrone, il venerabile falco e il magro cane giallo.

Da Storie delle Highland occidentali

(1) Apprendo dal Dizionario di fate, gnomi e folletti di Khatarine Briggs che i Gruagach maschi delle Highlands scozzesi sono spiriti simili ai Brownie, belli e slanciati, elegantemente vestiti di rosso e dotati di capelli biondi, dediti alla sorveglianza del bestiame. La maggior parte però sono brutti e trasandati e come i Brownie aiutano gli uomini nei lavori domestici e agricoli.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)