Once upon a time there was a youth called Moti, who was very big and strong, but the clumsiest creature you can imagine. So clumsy was he that he was always putting his great feet into the bowls of sweet milk or curds which his mother set out on the floor to cool, always smashing, upsetting, breaking, until at last his father said to him:

'Here, Moti, are fifty silver pieces which are the savings of years; take them and go and make your living or your fortune if you can.'

Then Moti started off one early spring morning with his thick staff over his shoulder, singing gaily to himself as he walked along.

In one way and another he got along very well until a hot evening when he came to a certain city where he entered the travellers' 'serai' or inn to pass the night. Now a serai, you must know, is generally just a large square enclosed by a high wall with an open colonnade along the inside all round to accommodate both men and beasts, and with perhaps a few rooms in towers at the corners for those who are too rich or too proud to care about sleeping by their own camels and horses. Moti, of course, was a country lad and had lived with cattle all his life, and he wasn't rich and he wasn't proud, so he just borrowed a bed from the innkeeper, set it down beside an old buffalo who reminded him of home, and in five minutes was fast asleep.

In the middle of the night he woke, feeling that he had been disturbed, and putting his hand under his pillow found to his horror that his bag of money had been stolen. He jumped up quietly and began to prowl around to see whether anyone seemed to be awake, but, though he managed to arouse a few men and beasts by falling over them, he walked in the shadow of the archways round the whole serai without coming across a likely thief. He was just about to give it up when he overheard two men whispering, and one laughed softly, and peering behind a pillar, he saw two Afghan horse dealers counting out his bag of money! Then Moti went back to bed!

In the morning Moti followed the two Afghans outside the city to the horsemarket in which they horses were offered for sale. Choosing the best-looking horse amongst them he went up to it and said:

'Is this horse for sale? may I try it?' and, the merchants assenting, he scrambled up on its back, dug in his heels, and off they flew. Now Moti had never been on a horse in his life, and had so much ado to hold on with both hands as well as with both legs that the animal went just where it liked, and very soon broke into a break-neck gallop and made straight back to the serai where it had spent the last few nights.

'This will do very well,' thought Moti as they whirled in at the entrance. As soon as the horse had arrived at its table it stopped of its own accord and Moti immediately rolled off; but he jumped up at once, tied the beast up, and called for some breakfast. Presently the Afghans appeared, out of breath and furious, and claimed the horse.

'What do you mean?' cried Moti, with his mouth full of rice, 'it's my horse; I paid you fifty pieces of silver for it - quite a bargain, I'm sure!'

'Nonsense! it is our horse,' answered one of the Afghans beginning to untie the bridle.

'Leave off,' shouted Moti, seizing his staff; 'if you don't let my horse alone I'll crack your skulls! you thieves! I know you! Last night you took my money, so to-day I took your horse; that's fair enough!'

Now the Afghans began to look a little uncomfortable, but Moti seemed so determined to keep the horse that they resolved to appeal to the law, so they went off and laid a complaint before the king that Moti had stolen one of their horses and would not give it up nor pay for it.

Presently a soldier came to summon Moti to the king; and, when he arrived and made his obeisance, the king began to question him as to why he had galloped off with the horse in this fashion. But Moti declared that he had got the animal in exchange for fifty pieces of silver, whilst the horse merchants vowed that the money they had on them was what they had received for the sale of other horses; and in one way and another the dispute got so confusing that the king (who really thought that Moti had stolen the horse) said at last, 'Well, I tell you what I will do. I will lock something into this box before me, and if he guesses what it is, the horse is his, and if he doesn't then it is yours.'

To this Moti agreed, and the king arose and went out alone by a little door at the back of the Court, and presently came back clasping something closely wrapped up in a cloth under his robe, slipped it into the little box, locked the box, and set it up where all might see.

'Now,' said the king to Moti, 'guess!'

It happened that when the king had opened the door behind him, Moti noticed that there was a garden outside: without waiting for the king's return he began to think what could be got out of the garden small enough to be shut in the box. 'Is it likely to be a fruit or a flower? No, not a flower this time, for he clasped it too tight. Then it must be a fruit or a stone. Yet not a stone, because he wouldn't wrap a dirty stone in his nice clean cloth. Then it is a fruit! And a fruit without much scent, or else he would be afraid that I might smell it. Now what fruit without much scent is in season just now? When I know that I shall have guessed the riddle!'

As has been said before, Moti was a country lad, and was accustomed to work in his father's garden. He knew all the common fruits, so he thought he ought to be able to guess right; but so as not to let it seem too easy, he gazed up at the ceiling with a puzzled expression, and looked down at the floor with an air or wisdom and his fingers pressed against his forehead, and then he said, slowly, with his eyes on the king:

'It is freshly plucked! It is round and it is red! It is a pomegranate!'

Now the king knew nothing about fruits except that they were good to eat; and, as for seasons, he asked for whatever fruit he wanted whenever he wanted it, and saw that he got it; so to him Moti's guess was like a miracle, and clear proof not only of his wisdom but of his innocence, for it was a pomegranate that he had put into the box. Of course when the king marvelled and praised Moti's wisdom, everybody else did so too; and, whilst the Afghans went off crestfallen, Moti took the horse and entered the king's service.

Very soon after this, Moti, who continued to live in the serai, came back one wet and stormy evening to find that his precious horse had strayed. Nothing remained of him but a broken halter cord, and no one knew what had become of him. After inquiring of everyone who was likely to know, Moti seized the cord and his big staff and sallied out to look for him. Away and away he tramped out of the city and into the neighbouring forest, tracking hoof-marks in the mud. Presently it grew late, but still Moti wandered on until suddenly in the gathering darkness he came right upon a tiger who was contentedly eating his horse.

'You thief!' shrieked Moti, and ran up and, just as the tiger, in astonishment, dropped a bone - whack! came Moti's staff on his head with such good will that the beast was half stunned and could hardly breathe or see. Then Moti continued to shower upon him blows and abuse until the poor tiger could hardly stand, whereupon his tormentor tied the end of the broken halter round his neck and dragged him back to the serai.

'If you had my horse,' he said, 'I will at least have you, that's fair enough!' And he tied him up securely by the head and heels, much as he used to tie the horse; then, the night being far gone, he flung himself beside him and slept soundly.

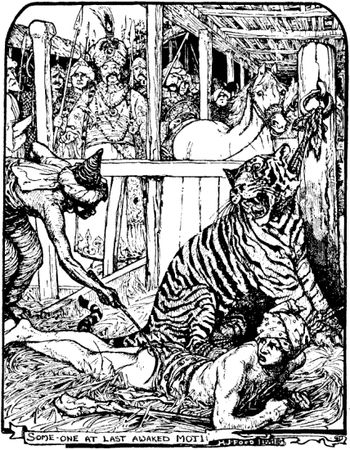

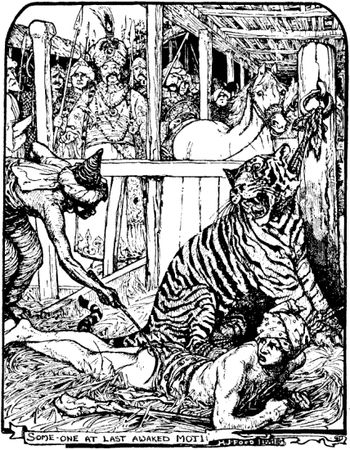

You cannot imagine anything like the fright of the people in the serai, when they woke up and found a tiger—very battered but still a tiger—securely tethered amongst themselves and their beasts! Men gathered in groups talking and exclaiming, and finding fault with the innkeeper for allowing such a dangerous beast into the serai, and all the while the innkeeper was just as troubled as the rest, and none dared go near the place where the tiger stood blinking miserably on everyone, and where Moti lay stretched out snoring like thunder.

At last news reached the king that Moti had exchanged his horse for a live tiger; and the monarch himself came down, half disbelieving the tale, to see if it were really true. Someone at last awaked Moti with the news that his royal master was come; and he arose yawning, and was soon delightedly explaining and showing off his new possession. The king, however, did not share his pleasure at all, but called up a soldier to shoot the tiger, much to the relief of all the inmates of the serai except Moti. If the king, however, was before convinced that Moti was one of the wisest of men, he was now still more convinced that he was the bravest, and he increased his pay a hundredfold, so that our hero thought that he was the luckiest of men.

A week or two after this incident the king sent for Moti, who on arrival found his master in despair. A neighbouring monarch, he explained, who had many more soldiers than he, had declared war against him, and he was at his wits' end, for he had neither money to buy him off nor soldiers enough to fight him - what was he to do?

'If that is all, don't you trouble,' said Moti. 'Turn out your men, and I'll go with them, and we'll soon bring this robber to reason.'

The king began to revive at these hopeful words, and took Moti off to his stable where he bade him choose for himself any horse he liked. There were plenty of fine horses in the stalls, but to the king's astonishment Moti chose a poor little rat of a pony that was used to carry grass and water for the rest of the stable.

'But why do you choose that beast?' said the king.

'Well, you see, your majesty,' replied Moti, 'there are so many chances that I may fall off, and if I choose one of your fine big horses I shall have so far to fall that I shall probably break my leg or my arm, if not my neck, but if I fall off this little beast I can't hurt myself much.'

A very comical sight was Moti when he rode out to the war. The only weapon he carried was his staff, and to help him to keep his balance on horseback he had tied to each of his ankles a big stone that nearly touched the ground as he sat astride the little pony. The rest of the king's cavalry were not very numerous, but they pranced along in armour on fine horses. Behind them came a great rabble of men on foot armed with all sorts of weapons, and last of all was the king with his attendants, very nervous and ill at ease. So the army started.

They had not very far to go, but Moti's little pony, weighted with a heavy man and two big rocks, soon began to lag behind the cavalry, and would have lagged behind the infantry too, only they were not very anxious to be too early in the fight, and hung back so as to give Moti plenty of time. The young man jogged along more and more slowly for some time, until at last, getting impatient at the slowness of the pony, he gave him such a tremendous thwack with his staff that the pony completely lost his temper and bolted. First one stone became untied and rolled away in a cloud of dust to one side of the road, whilst Moti nearly rolled off too, but clasped his steed valiantly by its ragged mane, and, dropping his staff, held on for dear life. Then, fortunately the other rock broke away from his other leg and rolled thunderously down a neighbouring ravine. Meanwhile the advanced cavalry had barely time to draw to one side when Moti came dashing by, yelling bloodthirsty threats to his pony:

'You wait till I get hold of you! I'll skin you alive! I'll wring your neck! I'll break every bone in your body!' The cavalry thought that this dreadful language was meant for the enemy, and were filled with admiration of his courage. Many of their horses too were quite upset by this whirlwind that galloped howling through their midst, and in a few minutes, after a little plunging and rearing and kicking, the whole troop were following on Moti's heels.

Far in advance, Moti continued his wild career. Presently in his course he came to a great field of castor-oil plants, ten or twelve feet high, big and bushy, but quite green and soft. Hoping to escape from the back of his fiery steed Moti grasped one in passing, but its roots gave way, and he dashed on, with the whole plant looking like a young tree flourishing in his grip.

The enemy were in battle array, advancing over the plain, their king with them confident and cheerful, when suddenly from the front came a desperate rider at a furious gallop.

'Sire!' he cried, 'save yourself! the enemy are coming!'

'What do you mean?' said the king.

'Oh, sire!' panted the messenger, 'fly at once, there is no time to lose. Foremost of the enemy rides a mad giant at a furious gallop. He flourishes a tree for a club and is wild with anger, for as he goes he cries, "You wait till I get hold of you! I'll skin you alive! I'll wring your neck! I'll break every bone in your body!" Others ride behind, and you will do well to retire before this whirlwind of destruction comes upon you.'

Just then out of a cloud of dust in the distance the king saw Moti approaching at a hard gallop, looking indeed like a giant compared with the little beast he rode, whirling his castor-oil plant, which in the distance might have been an oak tree, and the sound of his revilings and shoutings came down upon the breeze! Behind him the dust cloud moved to the sound of the thunder of hoofs, whilst here and there flashed the glitter of steel. The sight and the sound struck terror into the king, and, turning his horse, he fled at top speed, thinking that a regiment of yelling giants was upon him; and all his force followed him as fast as they might go. One fat officer alone could not keep up on foot with that mad rush, and as Moti came galloping up he flung himself on the ground in abject fear. This was too much for Moti's excited pony, who shied so suddenly that Moti went flying over his head like a sky rocket, and alighted right on the top of his fat foe.

Quickly regaining his feet Moti began to swing his plant round his head and to shout:

'Where are your men? Bring them up and I'll kill them. My regiments! Come on, the whole lot of you! Where's your king? Bring him to me. Here are all my fine fellows coming up and we'll each pull up a tree by the roots and lay you all flat and your houses and towns and everything else! Come on!'

But the poor fat officer could do nothing but squat on his knees with his hands together, gasping. At last, when he got his breath, Moti sent him off to bring his king, and to tell him that if he was reasonable his life should be spared. Off the poor man went, and by the time the troops of Moti's side had come up and arranged themselves to look as formidable as possible, he returned with his king. The latter was very humble and apologetic, and promised never to make war any more, to pay a large sum of money, and altogether do whatever his conqueror wished.

So the armies on both sides went rejoicing home, and this was really the making of the fortune of clumsy Moti, who lived long and contrived always to be looked up to as a fountain of wisdom, valour, and discretion by all except his relations, who could never understand what he had done to be considered so much wiser than anyone else.

A Pushto Story.

Moti

C’era una volta un giovane di nome Moti che era molto grande e forte, ma era anche la creatura più maldestra che possiate immaginare. Era così maldestro che metteva sempre i grossi piedi nelle ciotole di latte o di cagliata che sua madre metteva sul pavimento a raffreddare, rompendole, rovesciandole e spaccandole sempre finché alla fine suo padre gli disse:

”Moti, ecco qui cinquanta pezzi d’argento che sono i risparmi di tanti anni; prendili e va’ a guadagnarti da vivere o a fare fortuna, se puoi.”

Allora Moti partì una mattina presto a primavera con il pesante bastone sulle spalle, cantando allegramente tra sé mentre camminava da solo. In un modo o nell’altro tirò avanti molto bene fino a una calda sera in cui giunse in una certa città dove entrò in un caravanserraglio per viaggiatori per trascorrere la notte. Dovete sapere che un caravanserraglio generalmente è una vasta piazza cinta da alte mura con all’interno tutto attorno un colonnato aperto per alloggiare sia uomini che animali, e con forse poche stanze nelle torri d’angolo per coloro i quali sono abbastanza ricchi o troppo superbi per darsi la briga di dormire con i loro cammelli e cavalli. Moti naturalmente era un campagnolo e per tutta la vita aveva vissuto con il bestiame, non era né ricco né superbo così prese in prestito un letto dal padrone, lo mise accanto a un vecchio bufalo che gli rammentava casa sua e in cinque minuti si addormentò.

Si svegliò nel cuore della note, con la sensazione di essere stato disturbato e, mettendo la mano sotto il guanciale, si accorse con orrore che il borsellino con le monete era stato rubato. Balzò in piedi senza far rumore e cominciò ad aggirarsi furtivamente all’intorno per vedere se qualcuno fosse sveglio, ma, sebbene riuscisse a svegliare un po’ di uomini e di animali cadendo loro addosso, percorse nell’ombra tutti porticati dell’intero caravanserraglio senza imbattersi in un probabile ladro. Stava quasi per arrendersi quando sentì per caso due uomini che bisbigliavano e uno rideva sommessamente; facendo capolino da dietro una colonna, vide due mercanti afgani di cavalli che contavano a una a una le monete del suo borsellino! Allora Moti tornò a letto!

La mattina Moti seguì i due afgani fuori dalla città verso il mercato dei cavalli in cui i loro cavalli erano in vendita. Scegliendo tra di essi il cavallo dall’aspetto migliore, gli andò vicino e disse:

”È in vendita questo cavallo? Posso provarlo?” e, avendo i mercanti acconsentito, gli montò in groppa, vi piantò i talloni e cavalcò via. Dovete sapere che Moti non aveva mai avuto un cavallo in vita propria ed ebbe così tanta difficoltà a tenerlo tanto con entrambe le mani che con le gambe, che l’animale andava dove gli pareva e ben presto si lanciò al galoppo a rotta di collo e tornò dritto nel caravanserraglio in cui aveva trascorso le ultime notti.

”Andrà benissimo.” pensò Moti mentre correvano verso l’ingresso. Appena il cavallo fu arrivato al suo posto, si fermò di sua spontanea volontà e Moti rotolò giù immediatamente; ma balzò subito in piedi, legò l’animale e chiese la colazione. Di lì a poco comparvero gli afgani a reclamare il cavallo, ansanti e furibondi.

”Che cosa volete dire?” strillò Moti, con la bocca piena di riso, “è il mio cavallo; ve l’ho pagato cinquanta pezzi d’argento – proprio un bell’affare, senza dubbio!”

”Sciocchezze! È il nostro cavallo.” rispose uno degli afghani cominciando a sciogliere le briglie.

”Andatevene!” strillò Moti, afferrando il bastone, “se non lascerete stare il mio cavallo, vi romperò la testa! Ladri! Vi conosco! La scorsa notte avete preso il mio denaro, così oggi io prendo il vostro cavallo, mi sembra giusto!”

Gli afgani cominciavano a guardarlo un po’ a disagio, ma Moti sembrava così risoluto a tenere il cavallo che decisero di rivolgersi alla legge, così andarono a sporgere denuncia al re che Moti aveva rubato uno dei loro cavalli e non voleva né restituirlo né pagarlo.

Di lì a poco un soldato venne a convocare Moti dal re; e, quando fu arrivato e gli ebbe reso omaggio, il re cominciò con il chiedergli perché fosse scappato via a cavallo in quel modo. Moti dichiarò di aver preso l’animale in cambio di cinquanta pezzi d’argento, sebbene i mercanti di cavalli giurassero che il denaro che avevano con sé era ciò che avevano ricavato dalla vendita di altri cavalli; in un modo o nell’altro la disputa diventò così confusa che il re (il quale pensava davvero che Moti avesse rubato il cavallo) alla fine disse: “Ebbene, vi dirò che cosa farò. Chiuderò a chiave qualcosa in questa scatola davanti a me, se lui indovinerà che cosa sia. Il cavallo sarà suo; se non indovina, allora sarà vostro.”

Moti acconsentì e il re si alzò e se ne andò da solo attraverso una porticina sul retro della corte e di lì a poco tornò stringendo sotto la veste qualcosa strettamente avvolto in un panno, la fece scivolare nella scatoletta, la chiuse e la collocò dove tutti potessero vederla.

”Adesso indovina!” disse il re a Moti.

Si dava il caso che quando il mentre aveva aperto la porta davanti a sé, Moti avesse notato che fuori vi fosse un giardino; senza aspettare il ritorno del re, aveva incominciato a pensare che cosa vi potesse essere preso di abbastanza piccolo da essere chiuso nella scatola. “Potrebbe trattarsi di un frutto o di un fiore? No, stavolta non un fiore perché lo ha tenuto troppo stretto. Allora deve essere un frutto o una pietra. Eppure una pietra no, perché non avvolgerebbe una pietra sporca nel suo bell’abito pulito. Allora è un frutto! E un frutto senza troppo profumo altrimenti avrebbe paura che io lo annusassi. In questa stagione quale frutto c’è che non profuma troppo? Quando lo saprò, avrò risolto l’indovinello!”

Come vi avevo detto in precedenza, Moti era un ragazzo di campagna, abituato a lavorare nell’orto con il padre, conosceva tutti i frutti più comuni così pensava di essere in grado di indovinare; ma per non farlo sembrare troppo semplice, fissò il soffitto con un’espressione perplessa guardò il pavimento con aria sagace e le dita premute sulla fronte, poi disse, lentamente, con lo sguardo fisso in quello del re:

”È stato appena colto! È rotondo e rosso! È una melagrana!”

Il re non sapeva altro della frutta eccetto che fosse buona da mangiare; e, riguardo le stagioni, chiedeva qualsiasi frutto volesse in qualsiasi momento lo volesse, e lo riceveva; così per lui la supposizione di Moti era qualcosa di miracoloso, nonché prova evidente non solo della sua saggezza, ma anche della sua innocenza, perché era una melagrana ciò che aveva messo nella scatola. Naturalmente quando il re si stupì della saggezza di Moti e la elogiò, tutti gli altri fecero altrettanto; e mentre gli Afghani se ne andavano mortificati, Moti prese il cavallo ed entrò al servizio del re.

Poco tempo dopo tutto ciò Moti, che continuava a vivere nel caravanserraglio, in una tempestosa sera di pioggia tornò per scoprire il suo prezioso cavallo si era allontanato. Di lui non restava che la corda spezzata della cavezza e nessuna sapeva che ne fosse stato di lui. Dopo aver chiesto a chiunque probabilmente sapesse, Moti afferrò la corda e il grosso bastone e uscì di gran carriera a cercarlo. Cammina cammina, si aggirò per città e nella vicina foresta, seguendo le tracce degli zoccoli nel fango. Si fece tardi rapidamente, ma Moti ancora vagabondava finché improvvisamente nelle tenebre che avanzavano, giunse proprio vicino a una tigre che stava mangiando con soddisfazione il suo cavallo.

”Ladra!” strillò Moti e corse e, proprio mentre la tigre, stupita, lasciava cedere un osso, sbam! Il bastone di Morti le calò sulla testa con tanta buona lena che la belva ne fu mezzo stordita e a malapena poteva respirare o vedere. Allora Moti continuò a farle piovere addosso colpi e violenze che la povera tigre a malapena stava ritta, dopo di che il suo aguzzino le legò intorno al collo la cavezza rotta e la trascinò al caravanserraglio.

”Visto che hai preso il mio cavallo, alla fine io prenderò te, mi sembra giusto!” disse. E la legò saldamente per la testa e le estremità delle zampe, più di quanto fosse solito legare il cavallo; poi, siccome la notte era avanzata, gli si gettò di fianco e dormì saporitamente.

Non potete immaginare nulla di simile allo spavento degli occupanti del caravanserraglio quando la mattina si svegliarono e trovarono una tigre – assai malconcia, ma pur sempre una tigre - saldamente legata in mezzo a loro e agli animali! Gli uomini si raggrupparono tra commenti ed esclamazioni, lamentandosi con il gestore per aver accettato nel caravanserraglio una belva così pericolosa, mentre il gestore era preoccupato proprio quanto gli altri, e nessuno osava avvicinarsi al posto in cui stava la tigre, guardando ciascuno ad occhi socchiusi, e in cui Moti era giaceva lungo disteso, russando come un mantice.

Alla fine giunse all’orecchio del re la notizia che Moti aveva scambiato il proprio cavallo con una tigre viva; il re in persona scese, mezzo incredulo alla nuova, per vedere quanto vi fosse di vero. Qualcuno alla fine svegliò Moti con al notizia che il suo regale padrone stava venendo; si alzò sbadigliando e subito fu contento di spiegare ed esibire la sua nuova proprietà. Il re, in ogni modo, non condivideva affatto la sua soddisfazione, ma chiamò un soldato per sparare alla tigre, con grande sollievo di tutti gli ospiti del caravanserraglio escluso Moti. Se prima il re era persuaso che fosse uno degli uomini più saggi, adesso si era viepiù convinto che fosse il più coraggioso, e aumentò la sua paga di cento volte, così che il nostro eroe pensò di essere il più fortunato degli uomini.

Una settimana o due dopo questo incidente il re mandò a chiamare Moti, che al proprio arrivò trovò il padrone disperato. Gli spiegò che un sovrano vicino, il quale aveva molti più soldati di lui, gli aveva dichiarato guerra ed era al limite delle proprie risorse perché non aveva né denaro per corromperlo né abbastanza soldati per combatterlo – che cosa doveva fare?

”Se è tutto qui, non preoccupatevi,” disse Moti. “Mandate i vostri uomini, io andrò con loro e presto ridurremo alla ragione questo ladro.”

Il re cominciò a riprendersi a quelle parole piene di speranza e portò Moti nella stalla dove gli diede la possibilità di scegliersi qualsiasi cavallo gli piacesse. C’era una gran quantità di bei cavalli negli stalli, ma con sbigottimento da parte del re Moti scelse un povero cosino di pony che era usato per trasportare l’erba e l’acqua agli altri cavalli della stalla.

”Perché hai scelto questo animale?” disse il re.

Moti rispose: “Ebbene vedete, maestà, ci sono molte possibilità che io possa cadere e se scegliessi uno dei vostri bei cavalli grandi, lo farei da così in alto che probabilmente mi romperei una gamba o un braccio, se non l’osso del collo, ma se cadrò da questa bestiola, non mi farò molto male.”

Fu una visione assai buffa Moti che cavalcava verso la guerra. L’unica arma che portava era il suo bastone e per aiutarsi a mantenere l’equilibrio a cavallo, aveva legato a ciascuna caviglia una grossa pietra che quasi sfiorava il terreno mentre lui era a cavalcioni del pony. Il resto dei cavalieri del re non era assai numeroso, ma indossavano l’armatura cavalcando bei cavalli. Dietro di loro veniva una gran folla di fanti con le armi più disparate e dietro a tutti c’era il re con il suo attendente, assai nervoso e a disagio. Così l’armata partì.

Non erano arrivati molto lontano che il piccolo pony di Moti, appesantito da un uomo robusto e da due grosse pietre, ben presto cominciò a restare indietro alla cavalleria, e sarebbe rimasto anche dietro la fanteria, solo che non erano ansiosi di giungere troppo presto in battaglia e rallentavano in modo tale da dare a Moti tanto tempo. Il giovane procedette lentamente, sempre più adagio per diverso tempo, finché alla fine, diventando impaziente per la lentezza del pony, gli dette una tale tremenda botta con il bastone che il pony perse completamente la calma e si imbizzarrì. Dapprima una pietra fu sciolta e rotolò via in una nube di polvere da un lato della strada, mentre Moti quasi rotolò anche lui, ma afferrò coraggiosamente il cavallo per la criniera ispida e, mollando il bastone, si resse con tutte le forze. Allora fortunatamente l’altra pietra si staccò dalla gamba e rotolò fragorosamente nella gola vicina. Nel frattempo la cavalleria in avanguardia aveva a malapena avuto il tempo di farsi da parte quando Moti giunse impetuosamente, gridando sanguinarie minacce al pony:

”Aspetta che ti prenda! Ti spellerò vivo! Ti torcerò il collo! Ti spezzerò ogni osso del corpo!” La cavalleria pensò che le spaventose parole fosse rivolte al nemico e tutti furono ammirati per il suo coraggio. Anche molti dei loro cavalli furono così scombussolati da questo trambusto che galopparono nitrendo nel bel mezzo e in pochi minuti, dopo un po’ di affondi, impennate e calci, l’intera truppa era alle calcagna di Moti.

Molto avanti Moti continuava la sua folle corsa. Di lì a poco nel suo percorso giunse in un grande campo di ricino, alto dieci o dodici piedi, grande e folto, ma quasi completamente verde e soffice. Sperando di lanciarsi dalla groppa del suo irascibile destriero, Moti si afferrò a un ciuffo mentre passava, ma le radici furono estirpate e lui fu sbalzato, con l’intera pianta simile a un giovane albero rigoglioso nella sua stretta.

Il nemico era in assetto da battaglia, mentre avanzava nella pianura, e con esso il re, fiducioso e contento, quando improvvisamente di fronte a loro giunse un cavaliere disperato che galoppava furiosamente.

”Sire!” gridò “Mettevi in salvo! Il nemico sta arrivando!”

”Che cosa vuoi dire?” chiese il re.

”Oh, sire!” ansimò il messaggero, “andatevene subito, non c’è tempo da perdere. Nella prima fila dei nemici cavalca un gigante folle al galoppo furioso. Ostenta un albero come bastone ed è folle di rabbia perché mentre avanza, grida: ‘Aspetta che ti prenda! Ti spellerò vivo! Ti torcerò il collo! Ti spezzerò ogni osso del corpo!’ Gli altri cavalieri lo seguono e farete meglio a ritirarvi prima che questo turbine di distruzione si abbatta su di voi.”

Proprio allora in una nuvola di polvere in lontananza il re vide Moti avvicinarsi a folle corsa, e sembrava davvero un gigante a paragone del piccolo animale che cavalcava, roteando il ricino che a distanza poteva sembrare una quercia, e il suono delle sue minacce e delle sue urla giungeva trasportato dalla brezza! Dietro di lui si alzava una nuvola di polvere al rombo degli zoccoli mentre qua e là lampeggiava il luccichio dell’acciaio. Quella vista e quel suono gettarono il re nel terrore e, volgendo il cavallo, fuggì a gambe levate, pensando che un esercito di giganti urlanti gli fosse vicino; tutte le sue truppe lo seguirono più in fretta che poterono. Solo un grasso ufficiale non riuscì a stare in piedi in quella folle corsa, e siccome Moti giungeva al galoppo, si gettò per terra nel terrore assoluto. Questo fu troppo per l’agitato pony di Moti, il quale scartò così rapidamente che Moti volò sopra la sua testa come un razzo e atterrò dritto sul grasso nemico.

Rimettendosi in piedi rapidamente, Moti cominciò a mulinare la pianta attorno alla testa e a urlare:

”Uomini, dove siete? Portatemeli, che li ucciderò. Il mio reggimento! Venite, tutti voi! Dov’è il vostro re? Portatemelo. Stanno vendendo qui tutti i miei bravi compagni e solleveremo un albero dalle radici e abbatteremo tutti voi, le vostre case e città e qualsiasi altra cosa! Venite!”

Il povero ufficiale grasso non poté fare altro che inginocchiarsi a mani giunte, boccheggiando. Alla fine, quando riprese fiato, Moti lo mandò a prendere il suo re e a dirgli che se fosse stato ragionevole, la sua vita sarebbe stata risparmiata. Il pover’uomo se ne andò e, mentre le truppe erano arrivate al fianco di Moti e si erano sistemate per apparire temibili il più possibile, egli tornò con il re. Quest’ultimo era assai umile e mortificato, e promise che non avrebbe mai più dichiarato guerra, che avrebbe pagato una forte somma di denaro e che oltretutto avrebbe fatto qualsiasi cosa desiderasse il suo conquistatore.

Così gli eserciti di entrambi gli schieramenti tornarono a casa esultanti e ciò fu davvero l’origine della fortuna del goffo Moti, il quale visse a lungo e riuscì sempre ad apparire come una fonte di saggezza, di coraggio e di prudenza a tutti, tranne ai suoi parenti, i quali non capirono mai come avesse fatto ad essere considerato più saggio di chiunque altro.

Storia in lingua iranica parlata in Afghanistan e in Pakistan settentrionale

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)