How Ball-Carrier finished his task

After Ball-Carrier had managed to drown the Bad One so that he could not do any more mischief, he forgot the way to his grandmother's house, and could not find it again, though he searched everywhere. During this time he wandered into many strange places, and had many adventures; and one day he came to a hut where a young girl lived. He was tired and hungry and begged her to let him in and rest, and he stayed a long while, and the girl became his wife. One morning he saw two children playing in front of the hut, and went out to speak to them. But as soon as they saw him they set up cries of horror and ran away. 'They are the children of my sister who has been on a long journey,' replied his wife, 'and now that she knows you are my husband she wants to kill you.'

'Oh, well, let her try,' replied Ball-Carrier. 'It is not the first time people have wished to do that. And here I am still, you see!'

'Be careful,' said the wife, 'she is very cunning.' But at this moment the sister-in-law came up.

'How do you do, brother-in-law? I have heard of you so often that I am very glad to meet you. I am told that you are more powerful than any man on earth, and as I am powerful too, let us try which is the strongest.'

'That will be delightful,' answered he. 'Suppose we begin with a short race, and then we will go on to other things.'

'That will suit me very well,' replied the woman, who was a witch. 'And let us agree that the one who wins shall have the right to kill the other.'

'Oh, certainly,' said Ball-Carrier;' and I don't think we shall find a flatter course than the prairie itself—no one knows how many miles it stretches. We will run to the end and back again.'

This being settled they both made ready for the race, and Ball-Carrier silently begged the good spirits to help him, and not to let him fall into the hands of this wicked witch.

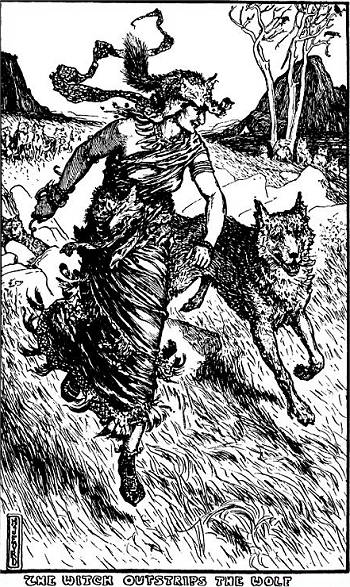

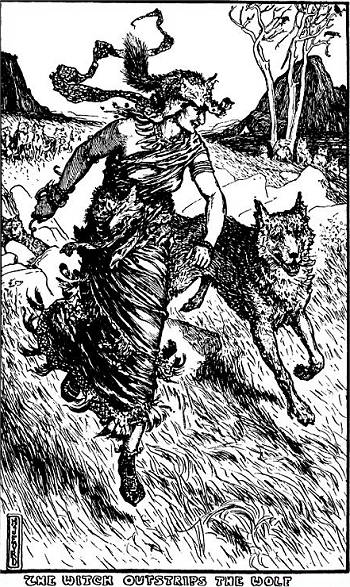

'When the sun touches the trunk of that tree we will start,' said she, as they both stood side by side. But with the first step Ball-Carrier changed himself into a wolf and for a long way kept ahead. Then gradually he heard her creeping up behind him, and soon she was in front. So Ball-Carrier took the shape of a pigeon and flew rapidly past her, but in a little while she was in front again and the end of the prairie was in sight. 'A crow can fly faster than a pigeon,' thought he, and as a crow he managed to pass her and held his ground so long that he fancied she was quite beaten. The witch began to be afraid of it too, and putting out all her strength slipped past him. Next he put on the shape of a hawk, and in this form he reached the bounds of the prairie, he and the witch turning homewards at the moment.

Bird after bird he tried, but every time the witch gained on him and took the lead. At length the goal was in sight, and Ball-Carrier knew that unless he could get ahead now he would be killed before his own door, under the eyes of his wife. His eyes had grown dim from fatigue, his wings flapped wearily and hardly bore him along, while the witch seemed as fresh as ever. What bird was there whose flight was swifter than his? Would not the good spirits tell him? Ah, of course he knew; why had he not thought of it at first and spared himself all that fatigue? And the next instant a humming bird, dressed in green and blue, flashed past the woman and entered the house.

The witch came panting up, furious at having lost the race which she felt certain of winning; and Ball-Carrier, who had by this time changed back into his own shape, struck her on the head and killed her.

For a long while Ball-Carrier was content to stay quietly at home with his wife and children, for he was tired of adventures, and only did enough hunting to supply the house with food. But one day he happened to eat some poisonous berries that he had found in the forest, and grew so ill that he felt he was going to die.

'When I am dead do not bury me in the earth,' he said, 'but put me over there, among that clump of trees.' So his wife and her three children watched by him as long as he was alive, and after he was dead they took him up and laid the body on a platform of stakes which they had prepared in the grove. And as they returned weeping to the hut they caught a glimpse of the ball rolling away down the path back to the old grandmother. One of the sons sprang forward to stop it, for Ball-Carrier had often told them the tale of how it had helped him to cross the river, but it was too quick for him, and they had to content themselves with the war club and bow and arrows, which were put carefully away.

By-and-by some travellers came past, and the chief among them asked leave to marry Ball-Carrier's daughter. The mother said she must have a little time to think over it, as her daughter was still very young; so it was settled that the man should go away for a month with his friends, and then come back to see if the girl was willing.

Now ever since Ball-Carrier's death the family had been very poor, and often could not get enough to eat. One morning the girl, who had had no supper and no breakfast, wandered off to look for cranberries, and though she was quite near home was astonished at noticing a large hut, which certainly had not been there when last she had come that way. No one was about, so she ventured to peep in, and her surprise was increased at seeing, heaped up in one corner, a quantity of food of all sorts, while a little robin redbreast stood perched on a beam looking down upon her.

'It is my father, I am sure,' she cried; and the bird piped in answer.

From that day, whenever they wanted food they went to the hut, and though the robin could not speak, he would hop on their shoulders and let them feed him with the food they knew he liked best.

When the man came back he found the girl looking so much prettier and fatter than when he had left her, that he insisted that they should be married on the spot. And the mother, who did not know how to get rid of him, gave in.

The husband spent all his time in hunting, and the family had never had so much meat before; but the man, who had seen for himself how poor they were, noticed with amazement that they did not seem to care about it, or to be hungry. 'They must get food from somewhere,' he thought, and one morning, when he pretended to be going out to hunt, he hid in a thicket to watch. Very soon they all left the house together, and walked to the other hut, which the girl's husband saw for the first time, as it was hid in a hollow. He followed, and noticed that each one went up to the redbreast, and shook him by the claw; and he then entered boldly and shook the bird's claw too. The whole party afterwards sat down to dinner, after which they all returned to their own hut.

The next day the husband declared that he was very ill, and could not eat anything; but this was only a presence so that he might get what he wanted. The family were all much distressed, and begged him to tell them what food he fancied.

'Oh! I could not eat any food,' he answered every time, and at each answer his voice grew fainter and fainter, till they thought he would die from weakness before their eyes.

'There must be some thing you could take, if you would only say what it is,' implored his wife.

'No, nothing, nothing; except, perhaps—but of course that is impossible!'

'No, I am sure it is not,' replied she; 'you shall have it, I promise—only tell me what it is.'

'I think—but I could not ask you to do such a thing. Leave me alone, and let me die quietly.'

'You shall not die,' cried the girl, who was very fond of her husband, for he did not beat her as most girls' husbands did. 'Whatever it is, I will manage to get it for you.'

'Well, then, I think, if I had that—redbreast, nicely roasted, I could eat a little bit of his wing!'

The wife started back in horror at such a request; but the man turned his face to the wall, and took no notice, as he thought it was better to leave her to herself for a little.

Weeping and wringing her hands, the girl went down to her mother. The brothers were very angry when they heard the story, and declared that, if any one were to die, it certainly should not be the robin. But all that night the man seemed getting weaker and weaker, and at last, quite early, the wife crept out, and stealing to the hut, killed the bird, and brought him home to her husband.

Just as she was going to cook it her two brothers came in. They cried out in horror at the sight, and, rushing out of the hut, declared they would never see her any more. And the poor girl, with a heavy heart, took the body of the redbreast up to her husband.

But directly she entered the room the man told her that he felt a great deal better, and that he would rather have a piece of bear's flesh, well boiled, than any bird, however tender. His wife felt very miserable to think that their beloved redbreast had been sacrificed for nothing, and begged him to try a little bit.

'You felt so sure that it would do you good before,' said she, 'that I can't help thinking it would quite cure you now.' But the man only flew into a rage, and flung the bird out of the window. Then he got up and went out.

Now all this while the ball had been rolling, rolling, rolling to the old grandmother's hut on the other side of the world, and directly it rolled into her hut she knew that her grandson must be dead. Without wasting any time she took a fox skin and tied it round her forehead, and fastened another round her waist, as witches always do when they leave their own homes. When she was ready she said to the ball: 'Go back the way you came, and lead me to my grandson.' And the ball started with the old woman following.

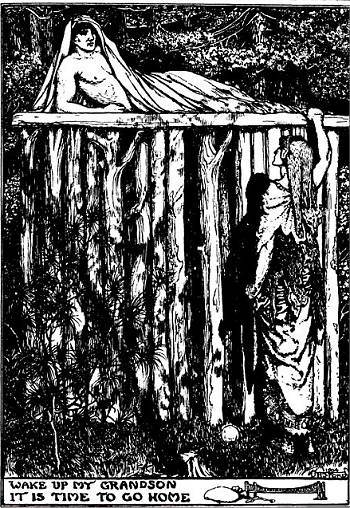

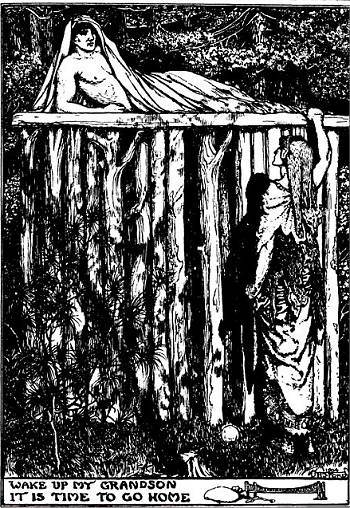

It was a long journey, even for a witch, but, like other things, it ended at last; and the old woman stood before the platform of stakes, where the body of Ball-Carrier lay.

'Wake up, my grandson, it is time to go home,' the witch said. And Ball-Carrier stepped down off the platform, and brought his club and bow and arrows out of the hut, and set out, for the other side of the world, behind the old woman.

When they reached the hut where Ball-Carrier had fasted so many years ago, the old woman spoke for the first time since they had started on their way.

'My grandson, did you ever manage to get that gold from the Bad One?'

'Yes, grandmother, I got it.'

'Where is it?' she asked.

'Here, in my left arm-pit,' answered he.

So she picked up a knife and scraped away all the gold which had stuck to his skin, and which had been sticking there ever since he first stole it. After she had finished she asked again:

'My grandson, did you manage to get that bridge from the Bad One?'

'Yes, grandmother, I got that too,' answered he.

'Where is it?' she asked, and Ball-Carrier lifted his right arm, and pointed to his arm-pit.

'Here is the bridge, grandmother,' said he.

Then the witch did something that nobody in the world could have guessed that she would do. First, she took the gold and said to Ball-carrier:

'My grandson, this gold must be hidden in the earth, for if people think they can get it when they choose, they will become lazy and stupid. But if we take it and bury it in different parts of the world they will have to work for it if they want it, and then will only find a little at a time.' And as she spoke, she pulled up one of the poles of the hut, and Ball-Carrier saw that underneath was a deep, deep hole, which seemed to have no bottom. Down this hole she poured all the gold, and when it was out of sight it ran about all over the world, where people that dig hard sometimes find it. And after that was done she put the pole back again.

Next she lifted down a spade from a high shelf, where it had grown quite rusty, and dug a very small hole on the opposite side of the hut—very small, but very deep.

'Give me the bridge,' said she, 'for I am going to bury it here. If anyone was to get hold of it, and find that they could cross rivers and seas without any trouble, they would never discover how to cross them for themselves. I am a witch, and if I had chosen I could easily have cast my spells over the Bad One, and have made him deliver them to you the first day you came into my hut. But then you would never have fasted, and never have planned how to get what you wanted, and never have known the good spirits, and would have been fat and idle to the end of your days. And now go; in that hut, which you can just see far away, live your father and mother, who are old people now, and need a son to hunt for them. You have done what you were set to do, and I need you no more.'

Then Ball-Carrier remembered his parents and went back to them.

[From Bureau of Ethnology. 'Indian Folklore.']

Come Porta-la-Palla terminò la sua impresa

Dopo che Porta-la-Palla era riuscito ad affogare Il Cattivo, così che non potesse più commettere alcuna malvagità, aveva dimenticato la strada per la casa della nonna e non riusciva a trovarla di nuovo benché la cercasse dappertutto. Durante quel periodo aveva vagato per molti luoghi strani e vissuto molte avventure; un giorno giunse in una capanna nella quale viveva una ragazza. Era stanco e affamato e la pregò di permettergli di entrare e riposare; vi rimase a lungo e la ragazza divenne sua moglie. Una mattina vide due bambini che giocavano davanti alla capanna e andò a parlare con loro. Ma appena lo videro, lanciarono grida di paura e corsero via. "Sono i bambini di mia sorella, che ha fatto un lungo viaggio" replicò sua moglie, "e ora che sai che tu sei mio marito, vuole ucciderti."

"Bene, lascia che ci provi, " rispose Porta-la-Palla. "Non è la prima volta che qualcuno abbia desiderato farlo. E sono ancora qui, come vedi!"

"Stai attento, " disse la moglie, " è molto astuta." Ma in quel momento venne la cognata.

"Come stai, cognato? Ho sentito parlare di te così spesso che sono molto contenta di incontrarti. Mi è stato detto che sei più potente di qualunque uomo sulla terra, e siccome anche io sono potente, vediamo chi tra noi è il più forte."

"Sarebbe assai piacevole, " rispose lui, "suppongo che potremmo cominciare con una breve corsa e poi potremmo fare altre cose."

"Mi va benissimo, " replicò la donna, che era una strega. "e accordiamoci che chi vincerà, avrà il diritto di uccidere l'altro."

"Certamente, " disse Porta-la-Palla, "e non credo che troveremo un percorso più pianeggiante del prato stesso - nessuno sa per quante miglia si estenda. Correremo fino alla fine e torneremo di nuovo indietro."

Stabilito ciò, entrambi furono pronti per la gara, Porta-la-Palla pregò silenziosamente gli spiriti buoni affinché lo aiutassero e non lo lasciassero cadere nelle grinfie di quella perfida strega.

"Partiremo quando il sole toccherà il tronco di quei tre alberi, " disse lei, ed entrambi si misero fianco a fianco. Al primo passo Porta-la-Palla si trasformò in un lupo e rimase in testa per un lungo tratto di strada. Poi pian piano la sentì avanzare quatta quatta dietro di sé e ben presto gli fu davanti. Allora Porta-la-Palla assunse l'aspetto di un piccione e volò rapidamente oltre lei, ma in un attimo lei fu in testa e la fine del prato era in vista. "Un corvo può volare più veloce di un piccione, " pensò lui e sotto l'aspetto di un corvo riuscì a sorpassarla e a guadagnare terreno tanto che fu sicuro che lei fosse completamente sconfitta. La strega cominciò a essere spaventata e mettendoci tutte le proprie forse, scivolò davanti a lui. Dopodiché Porta-la-Palla assunse l'aspetto di un falco e in tale forma raggiunse i confini del prato, mentre lui e la strega nel medesimo momento si giravano verso casa.

Provò a mutarsi di uccello in uccello, ma ogni volta la strega lo riagguantava e passava in testa. Infine la meta fu in vista e Porta-la-Palla sapeva che se non avesse riguadagnato terreno, sarebbe stato ucciso davanti alla porta, sotto gli occhi della moglie. I suoi occhi erano spenti per la fatica, le ali sbattevano stancamente e difficilmente lo avrebbero sostenuto ancora a lungo mentre la strega sembrava più riposta che mai. Quale uccello c'era, il cui volo fosse più veloce del suo? I buoni spiriti non glielo avrebbero detto? Ah, naturalmente lo sapeva; perché non ci aveva pensato prima, risparmiandosi tutta quella fatica? Un istante dopo un colibrì, dal piumaggio verde e blu, sorpassò velocemente la donna ed entrò in casa.

La strega giunse ansimando, furibonda per aver perso una gara che credeva vinta con certezza; Porta-la-Palla, che aveva ripreso in quel momento il proprio aspetto, la colpì sulla testa e la uccise.

Per parecchio tempo Porta-la-Palla fu contento di starsene tranquillamente a casa con la moglie e i bambini perché era stanco di avventure, e cacciava solo quel tanto che bastava per procurare il cibo a casa. Ma un giorno gli successe di mangiare alcune bacche velenose che aveva raccolto nella foresta e cadde così malato che si sentì come se stesse per morire.

"Quando sarò morto, non seppellirmi in terra, " disse, "ma mettimi lassù, tra quel gruppo di alberi." Così la moglie e i tre figli lo vegliarono finché fu vivo e dopo che morì, lo presero e posarono il corpo su una piattaforma di pali che avevano preparato nel boschetto. E mentre tornavano piangendo alla capanna, intravidero la palla che rotolava lungo il sentiero verso la vecchia nonna. Uno dei figli si gettò avanti per fermarla, perché Porta-la-Palla spesso aveva raccontato loro la storia di come la palla lo avesse aiutato ad attraversare il fiume, ma era troppo veloce per lui e dovettero accontentarsi del randello, dell'arco e delle frecce, che erano stati messi da parte con cura.

Subito vennero in fretta alcuni viaggiatori e il loro capo chiese in moglie la figlia di Porta-la-Palla. La madre disse che voleva un po' di tempo per pensarci perché la figlia era ancora molto giovane; così fu stabilito che l'uomo se ne andasse per un mese con i suoi amici e poi tornasse a vedere se la ragazza era disponibile.

Dalla morte di Porta-la-Palla la famiglia era diventata molto povera e spesso non aveva abbastanza da mangiare. Una mattina la ragazza, che non aveva né cenato né fatta colazione, vagava in cerca di mirtilli e benché fosse abbastanza vicina a casa, rimase sbalordita accorgendosi di una grande capanna che certamente non c'era l'ultima volta in cui aveva percorso quella strada. Non c'era nessuno nei paraggi, così osò sbirciare all'interno e la sua sorpresa crebbe nel vedere, ammucchiata in un angolo, una quantità di ogni sorta di cibo, mentre un piccolo pettirosso stava appollaiato su una trave, guardando in basso verso di lei.

"È mio padre, ne sono certa, " gridò e in risposta l'uccello cinguettò.

Da quel giorno, ogni volta in cui volevano cibo, andavano alla capanna e benché il pettirosso non potesse parlare, saltava sulle loro spalle e lasciava che lo nutrissero con il cibo che più gli piaceva.

Quando l'uomo tornò indietro, si accorse che la ragazza era assai più graziosa e robusta di quando l'aveva lasciata, così insistette perché potessero sposarsi sul posto. E la madre, che non sapeva come liberarsi di lui, gliela concesse.

Il marito trascorreva tutto il proprio tempo andando a caccia e la famiglia non aveva mai avuto prima tanta carne; ma l'uomo, che aveva visto con i propri occhi quanto fossero poveri, si accorse con stupore che non sembravano preoccuparsene, né essere affamati. "Devono prendere il cibo da qualche parte, " pensava, e una mattina, quando fece finta di andare a caccia, si nascose a spiare in un boschetto. Assai presto lasciarono la casa tutti insieme e s'incamminarono verso l'altra capanna, che il marito della ragazza vedeva per la prima volta, essendo celato in una valle. Li seguì e si accorse che ciascuno di loro andava dal pettirosso e lo scuoteva per gli artigli; allora entrò baldanzosamente e anche lui scosse gli artigli dell'uccello. Dopo che furono tornati alla loro capanna, tutti sedettero a cena.

Il giorno successivo il marito dichiarò di sentirsi male e che non avrebbe potuto mangiare niente; ma era solo un'apparenza per poter ottenere ciò che voleva. L'intera famiglia era assai angosciata e lo pregava di dire che ci cibo gradisse.

"Oh, non potrei mangiare niente, " rispondeva ogni volta, e ad ogni risposta la sua voce si faceva più fioca e più fioca, finché sembrò che stesse per morire di debolezza sotto i loro occhi.

"Deve esserci qualcosa che vorresti prendere, se solo tu ci dicessi che cos'è." implorava la moglie.

"Niente, no, niente, eccetto, forse… ma naturalmente è impossibile!"

"No, sono certa di no, " replicò lei; "lo avrai, te lo prometto… dimmi solo che cos'è."

"Penso… ma non potrei chiedervi di fare una cosa simile. Lasciatemi solo, lasciatemi morire in pace."

"Non morirai, " gridò la ragazza, che era assai innamorata del marito perché non la picchiava come facevano la maggior parte dei mariti delle ragazze. "Qualunque cosa sia, riuscirò ad averla per te."

"Beh, allora, penso che se avessi un pettirosso, arrostito al punto giusto, potrei mangiare un bocconcino della sua ala!"

La moglie rimase inorridita a una simile richiesta; allora l'uomo voltò la faccia verso il muro e non ci fece caso, pensando che fosse meglio lasciarla con se stessa per un po'.

Piangendo e torcendosi le mani, la ragazza andò dalla madre. I fratelli si arrabbiarono molto quando udirono la storia e dichiararono che, se qualcuno doveva morire, di certo non sarebbe stato il pettirosso. Ma per tutta la notte l'uomo sembrò diventare più debole e più debole, e infine, appena fu giorno, la moglie uscì di soppiatto e, entrando furtivamente nella capanna, uccise l'uccello e lo portò a casa al marito.

Proprio mentre lo stava cucinando, vennero i suoi due fratelli. Gridarono di orrore alla vista e, correndo fuori dalla capanna, dichiararono di non volerla vedere mai più. La povera ragazza, con il cuore pesante, portò il corpicino del pettirosso al marito.

Ma appena entrò nella stanza, l'uomo le disse che si sentiva molto meglio e che avrebbe voluto piuttosto un pezzo di carne d'orso, ben cotto, piuttosto che qualunque uccello per quanto tenero. La moglie si sentì assai infelice al pensiero che l'amato pettirosso fosse stato sacrificato per niente e lo pregò di prenderne un pezzetto.

"Prima eri così certo che ti avrebbe fatto bene, "disse, "che non posso fare a meno di pensare che ti gioverebbe adesso." Ma l'uomo si arrabbiò e gettò l'uccello dalla finestra poi si alzò e uscì.

Ora tutto ciò accadeva mente la palla stava rotolando, rotolando, rotolando verso la capanna della vecchia nonna dall'altra parte del mondo e appena rotolò nella sua capanna, lei seppe che suo nipote doveva essere morto. Senza perdere tempo, prese una pelle di volpe e se la avvolse intorno alla fronte, un'altra la fissò intorno alla vita, come fanno sempre le streghe quando lasciano le loro case. Quando fu pronta, disse alla palla: "Torna da dove sei venuta e conducimi da mio nipote." E la palla partì, seguita dalla vecchia.

Fu un viaggio lungo persino per una strega, ma, come tutte le cose, giunse alla fine; e la vecchia stette sotto la piattaforma di pali sulla quale giaceva il corpo di Porta-la-Palla.

"Svegliati, nipote, è ora di tornare a casa." disse la strega. Porta-la-Palla scese giù falla piattaforma, prese dalla capanna il randello, l'arco e le frecce e si mise in cammino, verso l'altra parte del mondo, dietro la vecchia.

Quando raggiunsero la capanna in cui Porta-la-Palla aveva digiunato tanti anni prima, la vecchia parlò per la prima volta da quando avevano intrapreso il loro cammino.

"Nipote, sei riuscito ad ottenere quell'oro da Il Cattivo?"

"Sì, nonna, l'ho avuto."

"Dov'è?" chiese lei.

"Qui, nella cicatrice del mio braccio sinistro." rispose lui.

Così lei brandì un coltello e grattò via tutto l'oro che gli si era attaccato alla pelle e che vi era fissato fin dalla prima volta in cui lo aveva rubato. Dopo che ebbe finito, lei chiese di nuovo:

"Nipote, sei riuscito a prendere quel ponte da Il Cattivo?"

"Sì, nonna, ho avuto anche quello." Rispose lui.

"Dov'è?" chiese lei e Porta-la-Palla sollevò il braccio destro e indicò la cicatrice.

"Il ponte è qui, nonna." disse.

Allora la strega fece qualcosa che nessuno al mondo avrebbe immaginato potesse fare. Prima prese l'oro e disse a Porta-la-Palla:

"Nipote mio, quest'oro deve essere nascosto nella terra, perché se la gente pensasse di poterlo prendere quando vogliono, diventeranno pigri e stupidi. Se lo prendiamo e lo seppelliamo in diversi punti della terra, dovranno lavorare per averlo e ne troveranno solo un poco alla volta." Come ebbe parlato, estrasse uno dei pali della capanna e Porta-la-Palla vide che sotto c'era una buca profondissima, che sembrava non avere fondo. Lei verso tutto l'oro nella buca e quando non fu più possibile vederlo, corse dappertutto nel mondo, dove la gente che scava lo avrebbe trovato con difficoltà. E dopo aver fatto ciò, rimise a posto il palo.

Poi tirò giù una vanga da un alto scaffale, sul quale si era piuttosto arrugginita, e scavò una piccola buca sul lato opposto della capanna - assai piccola, ma molto profonda.

"Dammi il ponte," disse lei, "perché lo possa seppellire qui. Se qualcuno ne entrasse in possesso e scoprisse di poter attraversare fiumi e mari senza fatica, non scoprirebbe mai come attraversarli con le proprie forze. Sono una strega, e se lo avessi scelto, avrei potuto facilmente gettare i miei incantesimi su il Cattivo e gli avrei fatto consegnare essi a te il primo giorno in cui venisti nella mia capanna. Ma poi non avresti digiunato e non avresti mai progettato come ottenere ciò che volevi, non avresti conosciuto gli spiriti buoni e saresti stato grasso e inattivo sino alla fine dei tuoi giorni. Ora va; in quella capanna che puoi vedere in lontananza, vivono tuo padre e tua madre, i quali ora sono vecchi e hanno bisogno di un figlio che vada a caccia per loro. Hai fatto ciò che era stato stabilito tu facessi e non ho più bisogno di te."

Allora Porta-la-Palla ricordò i genitori e tornò da loro.

(Dipartimento di Etnologia - "folklore dei nativi d'America")

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)