Once upon a time there lived two peasants who had three daughters, and, as generally happens, the youngest was the most beautiful and the best tempered, and when her sisters wanted to go out she was always ready to stay at home and do their work.

Years passed quickly with the whole family, and one day the parents suddenly perceived that all three girls were grown up, and that very soon they would be thinking of marriage.

'Have you decided what your husband's name is to be?' said the father, laughingly, to his eldest daughter, one evening when they were all sitting at the door of their cottage. 'You know that is a very important point!'

'Yes; I will never wed any man who is not called Sigmund,' answered she.

'Well, it is lucky for you that there are a great many Sigmunds in this part of the world,' replied her father, 'so that you can take your choice! And what do YOU say?' he added, turning to the second. 'Oh, I think that there is no name so beautiful as Sigurd,' cried she.

'Then you won't be an old maid either,' answered he. 'There are seven Sigurds in the next village alone! And you, Helga?'

Helga, who was still the prettiest of the three, looked up. She also had her favourite name, but, just as she was going to say it, she seemed to hear a voice whisper: 'Marry no one who is not called Habogi.'

The girl had never heard of such a name, and did not like it, so she determined to pay no attention; but as she opened her mouth to tell her father that her husband must be called Njal, she found herself answering instead: 'If I do marry it will be to no one except Habogi.'

'Who IS Habogi?' asked her father and sisters; 'We never heard of such a person.'

'All I can tell you is that he will be my husband, if ever I have one,' returned Helga; and that was all she would say.

Before very long the young men who lived in the neighbouring villages or on the sides of the mountains, had heard of this talk of the three girls, and Sigmunds and Sigurds in scores came to visit the little cottage. There were other young men too, who bore different names, though not one of them was called 'Habogi,' and these thought that they might perhaps gain the heart of the youngest. But though there was more than one 'Njal' amongst them, Helga's eyes seemed always turned another way.

At length the two elder sisters made their choice from out of the Sigurds and the Sigmunds, and it was decided that both weddings should take place at the same time. Invitations were sent out to the friends and relations, and when, on the morning of the great day, they were all assembled, a rough, coarse old peasant left the crowd and came up to the brides' father.

'My name is Habogi, and Helga must be my wife,' was all he said. And though Helga stood pale and trembling with surprise, she did not try to run away.

'I cannot talk of such things just now,' answered the father, who could not bear the thought of giving his favourite daughter to this horrible old man, and hoped, by putting it off, that something might happen. But the sisters, who had always been rather jealous of Helga, were secretly pleased that their bridegrooms should outshine hers.

When the feast was over, Habogi led up a beautiful horse from a field where he had left it to graze, and bade Helga jump up on its splendid saddle, all embroidered in scarlet and gold. 'You shall come back again,' said he; 'but now you must see the house that you are to live in.' And though Helga was very unwilling to go, something inside her forced her to obey.

The old man settled her comfortably, then sprang up in front of her as easily as if he had been a boy, and, shaking the reins, they were soon out of sight.

After some miles they rode through a meadow with grass so green that Helga's eyes felt quite dazzled; and feeding on the grass were a quantity of large fat sheep, with the curliest and whitest wool in the world.

'What lovely sheep! whose are they?' cried Helga.

'Your Habogi's,' answered he, 'all that you see belongs to him; but the finest sheep in the whole herd, which has little golden bells hanging between its horns, you shall have for yourself.'

This pleased Helga very much, for she had never had anything of her own; and she smiled quite happily as she thanked Habogi for his present.

They soon left the sheep behind them, and entered a large field with a river running through it, where a number of beautiful grey cows were standing by a gate waiting for a milk-maid to come and milk them.

'Oh, what lovely cows!' cried Helga again; 'I am sure their milk must be sweeter than any other cows. How I should like to have some! I wonder to whom they belong?'

'To your Habogi,' replied he; 'and some day you shall have as much milk as you like, but we cannot stop now. Do you see that big grey one, with the silver bells between her horns? That is to be yours, and you can have her milked every morning the moment you wake.'

And Helga's eyes shone, and though she did not say anything, she thought that she would learn to milk the cow herself. A mile further on they came to a wide common, with short, springy turf, where horses of all colours, with skins of satin, were kicking up their heels in play. The sight of them so delighted Helga that she nearly sprang from her saddle with a shriek of joy.

'Whose are they?' Oh! whose are they?' she asked. 'How happy any man must be who is the master of such lovely creatures!' 'They are your Habogi's,' replied he, 'and the one which you think the most beautiful of all you shall have for yourself, and learn to ride him.'

At this Helga quite forgot the sheep and the cow.

'A horse of my own!' said she. 'Oh, stop one moment, and let me see which I will choose. The white one? No. The chestnut? No. I think, after all, I like the coal-black one best, with the little white star on his forehead. Oh, do stop, just for a minute.'

But Habogi would not stop or listen. 'When you are married you will have plenty of time to choose one,' was all he answered, and they rode on two or three miles further.

At length Habogi drew rein before a small house, very ugly and mean-looking, and that seemed on the point of tumbling to pieces.

'This is my house, and is to be yours,' said Habogi, as he jumped down and held out his arms to lift Helga from the horse. The girl's heart sank a little, as she thought that the man who possessed such wonderful sheep, and cows, and horses, might have built himself a prettier place to live in; but she did not say so. And, taking her arm, he led her up the steps.

But when she got inside, she stood quite bewildered at the beauty of all around her. None of her friends owned such things, not even the miller, who was the richest man she knew. There were carpets everywhere, thick and soft, and of deep rich colours; and the cushions were of silk, and made you sleepy even to look at them; and curious little figures in china were scattered about. Helga felt as if it would take her all her life to see everything properly, and it only seemed a second since she had entered the house, when Habogi came up to her.

'I must begin the preparations for our wedding at once,' he said; 'but my foster-brother will take you home, as I promised. In three days he will bring you back here, with your parents and sisters, and any guests you may invite, in your company. By that time the feast will be ready.'

Helga had so much to think about, that the ride home appeared very short. Her father and mother were delighted to see her, as they did not feel sure that so ugly and cross-looking man as Habogi might not have played her some cruel trick. And after they had given her some supper they begged her to tell them all she had done. But Helga only told them that they should see for themselves on the third day, when they would come to her wedding.

It was very early in the morning when the party set out, and Helga's two sisters grew green with envy as they passed the flocks of sheep, and cows, and horses, and heard that the best of each was given to Helga herself; but when they caught sight of the poor little house which was to be her home their hearts grew light again.

'I should be ashamed of living in such a place,' whispered each to the other; and the eldest sister spoke of the carved stone over HER doorway, and the second boasted of the number of rooms SHE had. But the moment they went inside they were struck dumb with rage at the splendour of everything, and their faces grew white and cold with fury when they saw the dress which Habogi had prepared for his bride—a dress that glittered like sunbeams dancing upon ice.

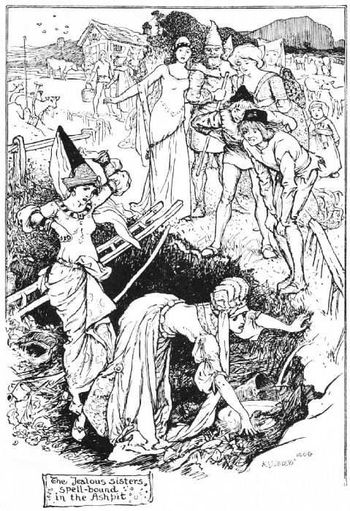

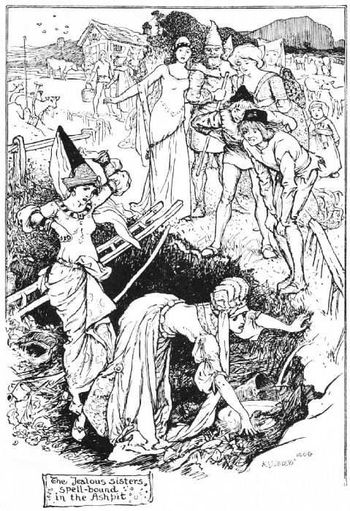

'She SHALL not look so much finer than us,' they cried passionately to each other as soon as they were alone; and when night came they stole out of their rooms, and taking out the wedding-dress, they laid it in the ash-pit, and heaped ashes upon it. But Habogi, who knew a little magic, and had guessed what they would do, changed the ashes into roses, and cast a spell over the sisters, so that they could not leave the spot for a whole day, and every one who passed by mocked at them.

The next morning when they all awoke the ugly tumble-down house had disappeared, and in its place stood a splendid palace. The guests' eyes sought in vain for the bridegroom, but could only see a handsome young man, with a coat of blue velvet and silver and a gold crown upon his head.

'Who is that?' they asked Helga.

'That is my Habogi,' said she.

From Neuislandischem Volksmarcher.

Habogi

C’erano una volta due contadini che avevano tre figlie e, come succede di solito, la più giovane era la più bella e la più amabile, e quando le sorelle volevano uscire, lei era sempre pronta a restare a casa a fare il loro lavoro.

Gli anni passavano in fretta per tutta la famiglia e un giorno i genitori si resero conto all’improvviso che tutte e tre le ragazze erano cresciute e assai presto avrebbero dovuto pensare al matrimonio.

”Hai deciso quale debba essere il nome di tuo marito?” disse ridendo il padre alla figlia maggiore, una sera in cui erano seduti sulla porta della casetta. “Sai che è una cosa molto importante!”

”Sì, non sposerò mai un uomo che non si chiami Sigismondo.” rispose lei.

”Ebbene, è una fortuna per te che da questi parti ci sia una gran quantità di Sigismondi,” rispose il padre; “così potrai fare la tua scelta! E tu che cosa dici?” aggiunse, rivolto alla seconda.

”Oh, io penso che non ci sia un nome meraviglioso come Sigfrido.” esclamò lei.

”Allora non diventerai neanche tu una zitella,” rispose lui. “Ci sono sette Sigfridi solo nel villaggio vicino! E tu, Elga?”

Elga, che era sempre la più bella delle tre, alzò lo sguardo. Anche lei aveva un nome preferito ma, proprio mentre stava per pronunciarlo, le parve di sentire una voce sussurrare: “Non sposare nessuno che non si chiami Habogi.”

La ragazza non aveva mai sentito un nome simile e non le piacque, così decise di non badarvi; ma come aprì la bocca per dire al padre che suo marito si sarebbe dovuto chiamare Neil, si ritrovò a rispondere invece: “Se mi sposerò, non sarà con nessuno tranne Habogi.”

”Chi è Habogi?” chiesero il padre e le sorelle; “non abbiamo mai sentito di una persona simile.”

”Tutto ciò che posso dirvi è che sarà mio marito, se mai ne avrò uno.” replicò Elga, e fu tutto ciò che ebbe da dire.

Dopo non molto tempo i giovanotti che vivevano nei villaggi vicini o sui fianchi della montagna avevano saputo di queste parole delle tre ragazze, e i Sigismondi e i Sigfridi vennero a decine in visita nella casetta. C’erano anche altri giovanotti, con nomi diversi, sebbene nessuno di loro si chiamava Habogi, e pensavano che forse sarebbero riusciti a conquistare il cuore della più giovane. Ma sebbene vi fosse più di un Neil tra di loro, gli occhi di Elga sembravano sempre rivolgersi altrove.

Infine le due sorelle maggiori fecero le loro scelte tra i Sigismondi e i Sigfridi, e fu deciso che entrambi i matrimoni sarebbero stati celebrati il medesimo giorno. Furono mandati gli inviti ai parenti e agli amici e quando la mattina del gran giorno furono tutti riuniti, un vecchio contadino rozzo uscì dal gruppo e si avvicinò al padre delle spose.

”Mi chiamo Habogi e Elga deve diventare mia moglie.” fu ciò che disse. Sebbene Elga fosse pallida e tremante per la sorpresa, non cercò di scappare.

”Non posso parlarne proprio adesso,” rispose il padre, che non sopportava il pensiero di dare la sua figlia prediletta a quel vecchio orribile, e sperava, rimandando, che potesse accadere qualcosa. Ma le sorelle, che erano sempre state gelose di Elga, furono segretamente compiaciute che i loro sposi le superassero in bellezza.

Quando la festa fu terminate, Habogi condusse un magnifico cavallo dal campo in cui l’aveva lasciato pascolare e ordinò a Elga di salire sulla splendida sella, tutta ricamata di porpora e d’oro. “Tornerai indietro di nuovo,” disse lui, “ma adesso dobbiamo andare a vedere la casa in cui dovrai vivere. “ e sebbene Elga fosse assai riluttante ad andare, qualcosa dentro di lei la induceva a obbedire.

Il vecchio la sistemò confortevolmente poi balzò in sella davanti a lei con l’agilità di un ragazzo e, scuotendo le redini, ben presto sparirono alla vista.

Dopo alcune miglia passarono per un prato di erba così verde che gli occhi di Elga quasi ne furono abbagliati; e sull’erba brucava una gran quantità di grasse pecore con la lana più bianca e più riccioluta del mondo.

”Che belle pecore! Di chi sono?” esclamò Elga.

”Del tuo Habogi,” rispose lui, “tutto ciò che vedi gli appartiene; la più bella pecora di tutto il gregge, quella che ha le campanelle d’oro tra le corna, l’avrai per te.”

Questo piacque molto a Elga, perchè non aveva mai posseduto nulla; sorrise felice e ringraziò Habogi per il dono.

Ben presto si lasciarono alle spalle le pecore ed entrarono in un vasto campo in cui scorreva un torrente, dove una gran quantità di meravigliose mucche stava vicino a un cancello in attesa che una mungitrice venisse a mungerle.

”Oh, che belle mucche!” esclamò di nuovo Elga; “sono certa che il loro latte debba essere più dolce di quello delle altre mucche: come mi piacerebbe averne un po’! Mi chiedo a chi appartengano.”

”Al tuo Habogi,” rispose lui; “e un giorno avrai più latte di quanto desideri, ma non possiamo fermarci ora. Vedi quella grossa mucca grigia con campanelle d’argento tra le corna? Sarà tua e potrai avere il suo latte ogni mattina al risveglio.”

Gli occhi di Elga brillarono e, sebbene non dicesse niente, pensò che avrebbe voluto imparare a mungerla da sé.

Un miglio più avanti giunsero ad un ampio pascolo dall’erba corta e morbida, dove cavalli di tutti i colori, con i manti come seta, stavano scalciando con gli zoccoli per gioco. La loro vista piacque tanto a Elga che quasi balzò di sella con un grido di gioia.

”Di chi sono? Oh! Di chi sono?” chiese. “Come deve essere felice qualunque uomo sia il padrone di queste splendide creature!”

”Sono del tuo Habogi,” rispose lui, “e quello che ti sembra il più bello di tutti sarà tuo e imparerai a cavalcarlo.”

A queste parole Elga quasi dimenticò la pecora e la mucca.

”Un cavallo tutto per me!” disse lei. “Oh, fermiamoci un momento e lasciami vedere quale potrei scegliere. Quello bianco? No. Quello marrone? No. Dopo tutto penso di preferire quello nero carbone con la stella bianca in fronte. Oh, fermiamoci solo un minuto.”

Ma Habogi non volle fermarsi o ascoltare. “Quando sarai sposata avrai tutto il tempo per sceglierne uno.” fu tutto ciò che rispose, e cavalcarono ancora due o tre miglia.

Infine Habogi tirò le redini davanti a una casetta, assai brutta e modesta a vedersi, che sembrava sul punto di cadere a pezzi.

”Questa è la mia casa e sarà la tua,” disse Habogi, come fu sceso e tendendo le braccia per farla scendere da cavallo. Il cuore della ragazza cedette un po’ perché pensava che un uomo che possedeva pecore, mucche e cavalli così belli si fosse costruito un posto più grazioso in cui vivere; ma non lo disse. E, presala per un braccio, la guidò sugli scalini.

Quando fu all’interno, fu sconcertata dalla bellezza di ciò che la circondava. Nessuno dei suoi amici possedeva cose simili, nemmeno il mugnaio che era l’uomo più ricco che conoscesse. C’erano tappeti dappertutto, folti e morbidi, dai colori caldi e intesi; e cuscini di seta che vi avrebbero fatto addormentare al solo guardarli; e qua e là erano sparpagliate strane statuine di porcellana . Elga si sentiva come se le occorresse tutta la vita per vedere con agio ogni cosa, e le era sembrato che fosse passato un solo minuto da che era entrata in casa, quando Habogi le si avvicinò.

”Devo cominciare subito i preparativi per le nostre nozze,” disse, “ma il mio fratello adottivo ti porterà a casa, come ho promesso. Fra tre giorni ti riporterà qui con i tuoi genitori e le tue sorelle e ogni altro ospite tu voglia invitare a farti compagnia. Per quel momento la festa sarà pronta.”

Elga aveva così tante cose a cui pensare che il ritorno a casa le sembrò assai rapido. Il padre e la madre furono felici di vederla perché non erano sicuri che un uomo brutto e bisbetico come Habogi non avesse potuto giocare loro qualche perfido tiro. E dopo che le ebbero dato la cena, la pregarono di raccontare loro tutto ciò che aveva fatto. Elga disse solo che lo avrebbero visto da soli il terzo giorno, quando sarebbero venuti al matrimonio.

Era mattina assai presto quando la festa fu approntata, e le due sorelle di Elga divennero verdi di invidia mentre superavano i greggi di pecore, le mucche e i cavalli e sentirono che i migliori di ciascuno era stato dato a Elga; ma quando dettero un’occhiata alla povera abitazione che sarebbe stata la sua casa, i loro cuori si risollevarono.

”Io mi vergognerei di vivere in un posto simile.” sussurrarono l’una all’altra, e la maggiore parlò della pietra scolpita sulla sua soglia e la seconda si vantò del numero di stanze che aveva. Ma nel momento in cui entrarono, ammutolirono per la rabbia di fronte allo splendore di ogni cosa, e i loro volti si fecero bianchi e gelidi di collera quando videro l’abito che Habogi aveva preparato per la sua sposa, un abito che scintillava come raggi di sole che danzassero sul ghiaccio.

”Non apparirà più bella di noi,” esclamarono con fervore l’uno all’altra quando furono sole; e quando scese la notte, scivolarono fuori dalle loro stanze e, prendendo il vestito di nozze, lo gettarono nel ceneratoio (1) e vi ammucchiarono sopra la cenere. Ma Habogi, che conosceva un po’ di magia, e aveva indovinato che cosa volessero fare, tramutò la cenere in rose e gettò un incantesimo sulle sorelle, così che non poterono lasciare il posto per l’intero giorno e ognuno che passava si faceva beffe di loro.

La mattina seguente, quando tutti si svegliarono, la brutta casa diroccata era sparita e al suo posto sorgeva uno splendido palazzo. Gli occhi degli ospiti cercarono invano lo sposo, ma videro solo un affascinante giovane con un mantello di velluto blu e d’argento e con una corona in testa.

“Chi è?” chiesero a Elga

”È il mio Habogi.” rispose lei.

Fiaba popolare islandese

(1) luodo destinato alla raccolta della cenere

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)