Once upon a time there lived by herself, in a city, an old woman who was desperately poor. One day she found that she had only a handful of flour left in the house, and no money to buy more nor hope of earning it. Carrying her little brass pot, very sadly she made her way down to the river to bathe and to obtain some water, thinking afterwards to come home and to make herself an unleavened cake of what flour she had left; and after that she did not know what was to become of her.

Whilst she was bathing she left her little brass pot on the river bank covered with a cloth, to keep the inside nice and clean; but when she came up out of the river and took the cloth off to fill the pot with water, she saw inside it the glittering folds of a deadly snake. At once she popped the cloth again into the mouth of the pot and held it there; and then she said to herself:

‘Ah, kind death! I will take thee home to my house, and there I will shake thee out of my pot and thou shalt bite me and I will die, and then all my troubles will be ended.’

With these sad thoughts in her mind the poor old woman hurried home, holding her cloth carefully in the mouth of the pot; and when she got home she shut all the doors and windows, and took away the cloth, and turned the pot upside down upon her hearthstone. What was her surprise to find that, instead of the deadly snake which she expected to see fall out of it, there fell out with a rattle and a clang a most magnificent necklace of flashing jewels!

For a few minutes she could hardly think or speak, but stood staring; and then with trembling hands she picked the necklace up, and folding it in the corner of her veil, she hurried off to the king’s hall of public audience.

‘A petition, O king!’ she said. ‘A petition for thy private ear alone!’ And when her prayer had been granted, and she found herself alone with the king, she shook out her veil at his feet, and there fell from it in glittering coils the splendid necklace. As soon as the king saw it he was filled with amazement and delight, and the more he looked at it the more he felt that he must possess it at once. So he gave the old woman five hundred silver pieces for it, and put it straightway into his pocket. Away she went full of happiness; for the money that the king had given her was enough to keep her for the rest of her life.

As soon as he could leave his business the king hurried off and showed his wife his prize, with which she was as pleased as he, if not more so; and, as soon as they had finished admiring the wonderful necklace, they locked it up in the great chest where the queen’s jewellery was kept, the key of which hung always round the king’s neck.

A short while afterwards, a neighbouring king sent a message to say that a most lovely girl baby had been born to him; and he invited his neighbours to come to a great feast in honour of the occasion. The queen told her husband that of course they must be present at the banquet, and she would wear the new necklace which he had given her. They had only a short time to prepare for the journey, and at the last moment the king went to the jewel chest to take out the necklace for his wife to wear, but he could see no necklace at all, only, in its place, a fat little boy baby crowing and shouting. The king was so astonished that he nearly fell backwards, but presently he found his voice, and called for his wife so loudly that she came running, thinking that the necklace must at least have been stolen.

‘Look here! look!’ cried the king, ‘haven’t we always longed for a son? And now heaven has sent us one!’

‘What do you mean?’ cried the queen. ‘Are you mad?’

‘Mad? no, I hope not,’ shouted the king, dancing in excitement round the open chest. ‘Come here, and look! Look what we’ve got instead of that necklace!’

Just then the baby let out a great crow of joy, as though he would like to jump up and dance with the king; and the queen gave a cry of surprise, and ran up and looked into the chest.

‘Oh!’ she gasped, as she looked at the baby, ‘what a darling! Where could he have come from?’

‘I’m sure I can’t say,’ said the king; ‘all I know is that we locked up a necklace in the chest, and when I unlocked it just now there was no necklace, but a baby, and as fine a baby as ever was seen.’

By this time the queen had the baby in her arms. ‘Oh, the blessed one!’ she cried, ‘fairer ornament for the bosom of a queen than any necklace that ever was wrought. Write,’ she continued, ‘write to our neighbour and say that we cannot come to his feast, for we have a feast of our own, and a baby of our own! Oh, happy day!’

So the visit was given up; and, in honour of the new baby, the bells of the city, and its guns, and its trumpets, and its people, small and great, had hardly any rest for a week; there was such a ringing, and banging, and blaring, and such fireworks, and feasting, and rejoicing, and merry-making, as had never been seen before.

A few years went by; and, as the king’s boy baby and his neighbour’s girl baby grew and throve, the two kings arranged that as soon as they were old enough they should marry; and so, with much signing of papers and agreements, and wagging of wise heads, and stroking of grey beards, the compact was made, and signed, and sealed, and lay waiting for its fulfilment. And this too came to pass; for, as soon as the prince and princess were eighteen years of age, the kings agreed that it was time for the wedding; and the young prince journeyed away to the neighbouring kingdom for his bride, and was there married to her with great and renewed rejoicings.

Now, I must tell you that the old woman who had sold the king the necklace had been called in by him to be the nurse of the young prince; and although she loved her charge dearly, and was a most faithful servant, she could not help talking just a little, and so, by-and-by, it began to be rumoured that there was some magic about the young prince’s birth; and the rumour of course had come in due time to the ears of the parents of the princess. So now that she was going to be the wife of the prince, her mother (who was curious, as many other people are) said to her daughter on the eve of the ceremony:

‘Remember that the first thing you must do is to find out what this story is about the prince. And in order to do it, you must not speak a word to him whatever he says until he asks you why you are silent; then you must ask him what the truth is about his magic birth; and until he tells you, you must not speak to him again.’

And the princess promised that she would follow her mother’s advice.

Therefore when they were married, and the prince spoke to his bride, she did not answer him. He could not think what was the matter, but even about her old home she would not utter a word. At last he asked why she would not speak; and then she said:

‘Tell me the secret of your birth.’

Then the prince was very sad and displeased, and although she pressed him sorely he would not tell her, but always reply:

‘If I tell you, you will repent that ever you asked me.’

For several months they lived together; and it was not such a happy time for either as it ought to have been, for the secret was still a secret, and lay between them like a cloud between the sun and the earth, making what should be fair, dull and sad.

At length the prince could bear it no longer; so he said to his wife one day: ‘At midnight I will tell you my secret if you still wish it; but you will repent it all your life.’ However, the princess was overjoyed that she had succeeded, and paid no attention to his warnings.

That night the prince ordered horses to be ready for the princess and himself a little before midnight. He placed her on one, and mounted the other himself, and they rode together down to the river to the place where the old woman had first found the snake in her brass pot. There the prince drew rein and said sadly: ‘Do you still insist that I should tell you my secret?’ And the princess answered ‘Yes.’ ‘If I do,’ answered the prince, ‘remember that you will regret it all your life.’ But the princess only replied ‘Tell me!’

‘Then,’ said the prince, ‘know that I am the son of the king of a far country, but by enchantment I was turned into a snake.’

The word ‘snake’ was hardly out of his lips when he disappeared, and the princess heard a rustle and saw a ripple on the water; and in the faint moonlight she beheld a snake swimming into the river. Soon it disappeared and she was left alone. In vain she waited with beating heart for something to happen, and for the prince to come back to her. Nothing happened and no one came; only the wind mourned through the trees on the river bank, and the night birds cried, and a jackal howled in the distance, and the river flowed black and silent beneath her.

In the morning they found her, weeping and dishevelled, on the river bank; but no word could they learn from her or from anyone as to the fate of her husband. At her wish they built on the river bank a little house of black stone; and there she lived in mourning, with a few servants and guards to watch over her.

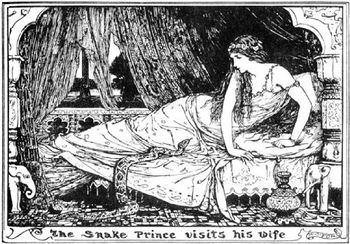

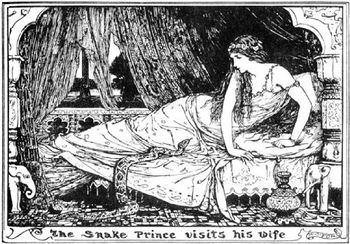

A long, long time passed by, and still the princess lived in mourning for her prince, and saw no one, and went nowhere away from her house on the river bank and the garden that surrounded it. One morning, when she woke up, she found a stain of fresh mud upon the carpet. She sent for the guards, who watched outside the house day and night, and asked them who had entered her room while she was asleep. They declared that no one could have entered, for they kept such careful watch that not even a bird could fly in without their knowledge; but none of them could explain the stain of mud. The next morning, again, the princess found another stain of wet mud, and she questioned everyone most carefully; but none could say how the mud came there. The third night the princess determined to lie awake herself and watch; and, for fear that she might fall asleep, she cut her finger with a penknife and rubbed salt into the cut, that the pain of it might keep her from sleeping. So she lay awake, and at midnight she saw a snake come wriggling along the ground with some mud from the river in its mouth; and when it came near the bed, it reared up its head and dropped its muddy head on the bedclothes. She was very frightened, but tried to control her fear, and called out:

‘Who are you, and what do you here?’

And the snake answered:

‘I am the prince, your husband, and I am come to visit you.’

Then the princess began to weep; and the snake continued:

‘Alas! did I not say that if I told you my secret you would repent it? and have you not repented?’

‘Oh, indeed!’ cried the poor princess, ‘I have repented it, and shall repent it all my life! Is there nothing I can do?’

And the snake answered:

‘Yes, there is one thing, if you dared to do it.’

‘Only tell me,’ said the princess, ‘and I will do anything!’

‘Then,’ replied the snake, ‘on a certain night you must put a large bowl of milk and sugar in each of the four corners of this room. All the snakes in the river will come out to drink the milk, and the one that leads the way will be the queen of the snakes. You must stand in her way at the door, and say: “Oh, Queen of Snakes, Queen of Snakes, give me back my husband!” and perhaps she will do it. But if you are frightened, and do not stop her, you will never see me again.’ And he glided away.

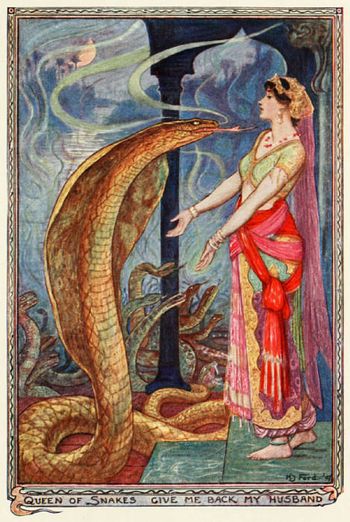

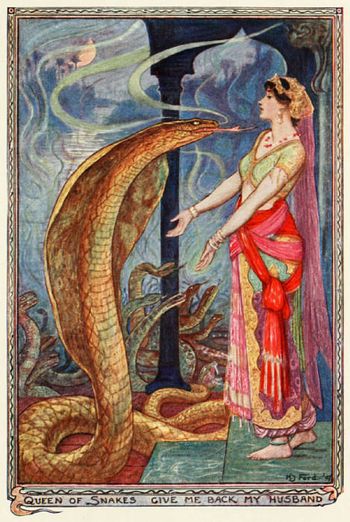

On the night of which the snake had told her, the princess got four large bowls of milk and sugar, and put one in each corner of the room, and stood in the doorway waiting. At midnight there was a great hissing and rustling from the direction of the river, and presently the ground appeared to be alive with horrible writhing forms of snakes, whose eyes glittered and forked tongues quivered as they moved on in the direction of the princess’s house. Foremost among them was a huge, repulsive scaly creature that led the dreadful procession. The guards were so terrified that they all ran away; but the princess stood in the doorway, as white as death, and with her hands clasped tight together for fear she should scream or faint, and fail to do her part. As they came closer and saw her in the way, all the snakes raised their horrid heads and swayed them to and fro, and looked at her with wicked beady eyes, while their breath seemed to poison the very air. Still the princess stood firm, and, when the leading snake was within a few feet of her, she cried: ‘Oh, Queen of Snakes, Queen of Snakes, give me back my husband!’ Then all the rustling, writhing crowd of snakes seemed to whisper to one another ‘Her husband? her husband?’ But the queen of snakes moved on until her head was almost in the princess’s face, and her little eyes seemed to flash fire. And still the princess stood in the doorway and never moved, but cried again: ‘Oh, Queen of Snakes, Queen of Snakes, give me back my husband!’ Then the queen of snakes replied: ‘To-morrow you shall have him—to-morrow!’ When she heard these words and knew that she had conquered, the princess staggered from the door, and sank upon her bed and fainted. As in a dream, she saw that her room was full of snakes, all jostling and squabbling over the bowls of milk until it was finished. And then they went away.

In the morning the princess was up early, and took off the mourning dress which she had worn for five whole years, and put on gay and beautiful clothes. And she swept the house and cleaned it, and adorned it with garlands and nosegays of sweet flowers and ferns, and prepared it as though she were making ready for her wedding. And when night fell she lit up the woods and gardens with lanterns, and spread a table as for a feast, and lit in the house a thousand wax candles. Then she waited for her husband, not knowing in what shape he would appear. And at midnight there came striding from the river the prince, laughing, but with tears in his eyes; and she ran to meet him, and threw herself into his arms, crying and laughing too.

So the prince came home; and the next day they two went back to the palace, and the old king wept with joy to see them. And the bells, so long silent, were set a-ringing again, and the guns firing, and the trumpets blaring, and there was fresh feasting and rejoicing.

And the old woman who had been the prince’s nurse became nurse to the prince’s children—at least she was called so; though she was far too old to do anything for them but love them. Yet she still thought that she was useful, and knew that she was happy. And happy, indeed, were the prince and princess, who in due time became king and queen, and lived and ruled long and prosperously.

Major Campbell, Feroshepore.

Il principe serpente

C’era una volta una vecchia che viveva in una città ed era disperatamente povera. Un giorno si accorse che in casa le era rimasta solo una manciata di farina e non aveva denaro per comperarne altra, né speranza di guadagnarne. Trasportando il suo piccolo vaso di ottone, prese tristemente la strada per il fiume per bagnarsi e attingere un po’ d’acqua, pensando poi di tornare a casa e farsi una focaccia non lievitata con la farina che le era rimasta; e dopo non sapeva che cosa ne sarebbe stato di lei.

Mentre si bagnava, lasciò il piccolo vaso di ottone sulla riva, coperto con un panno per tenerlo pulito all’interno, ma quando uscì dal fiume e tolse il panno per riempire d’acqua il piccolo vaso, vide dentro le spire luccicanti di un serpente letale. Subito ficcò di nuovo il panno sull’imboccatura del vaso e ve lo tenne, poi si disse:

‘Ah, dolce morte! Ti porterò a casa con me e lì ti scuoterò fuori dal mio vaso, tu mi morderai e io morirò, allora le mie tribolazioni saranno finite’

Con questi tristi pensieri in testa la povera donna tornò in fretta a casa, tenendo con cura il panno sulla bocca del vaso; quando fu a casa, chiuse tutte le porte e le finestre, tolse il panno e capovolse il vaso sulla pietra del focolare. Quale fu la sua sorpresa nello scoprire che, invece del serpente letale che si aspettava di veder cadere, era caduta con un rumore secco e un suono metallico una splendida collana di pietre scintillanti.

Per qualche minuto seppe a malapena che pensare o dire e rimase a fissarla, poi prese la collana con mani tremanti e, nascondendola in un lembo del velo, corse nella sala delle udienze pubbliche del re.

“Una petizione, maestà!” disse “Una petizione in privato solo per le vostre orecchie!” e quando la sua preghiera fu esaudita e si trovò sola con il re, scosse il velo ai suoi piedi e da lì cadde la splendida collana in una spirale scintillante. Appena il re la vide, fu stupefatto e compiaciuto, e più la guardava, più desiderava che diventasse subito sua. Così diede alla vecchia cinquecento pezzi d’argento per la collana e la infilò in tasca senza indugio. La vecchia andò via felicissima perché le monete che il re le aveva dato le sarebbero bastate per il resto della vita.

Appena poté liberarsi degli impegni ufficiali, il re corse a mostrare il gioiello alla moglie, che ne fu compiaciuta quanto lui, se non di più; appena ebbero finito di ammirare la meravigliosa collana, la chiusero nel grande forziere in cui la regina teneva i gioielli, la cui chiave era appesa al collo del re.

Poco dopo un re vicino mandò un messaggio per annunciare che gli era nata la più adorabile bambina e invitava i vicini a partecipare alla grande festa in onore dell’evento. La regina disse al marito che naturalmente avrebbero partecipato al banchetto e che intendeva indossare la nuova collana che le aveva dato. Avevano solo poco tempo per prepararsi al viaggio e all’ultimo momento il re andò prendere nel forziere la collana per sua moglie, ma non vide nessuna collana, solo al suo posto c’era un bambino grassottello che vagiva e cacciava gridolini. Il re fu così sbalordito che quasi cadde all’indietro, ma poco dopo ritrovò la voce e chiamò così forte la moglie che lei venne di corsa, pensando che la collana infine fosse stata rubata.

“Guarda qui! Guarda!” gridava il re “Non abbiamo sempre desiderato un figlio? E adesso il cielo ce ne ha mandato uno!”

“Che vuoi dire?” strillò la regina “Sei pazzo?”

“Pazzo? No, spero di no,” urlò il re, ballando eccitato intorno al forziere aperto. “Vieni qui e guarda! Guarda che cosa abbiamo invece di quella collana!”

Proprio allora il bambino emise un grande grido di gioia, come se volesse saltare e ballare con il re, e la regina gettò un grido di sorpresa e corse a guardare nel forziere.

“Che tesoro! Da dove può essere venuto?” ansimò, mentre guardava il bambino.

“Di certo non so che dire,” disse il re “tutto ciò che so è che avevamo chiuso una collana in questo forziere e quando l’ho aperto giusto poco fa non c’era nessuna collana, ma un bambino, e il bambino più bello che si sia mai visto.”

Nel frattempo la regina aveva preso in braccio il bambino. “Sia benedetto!” esclamò “Il più bell’ornamento per il seno di una regina che qualsiasi collana mai forgiata. Scrivi,” continuò “scrivi al nostro vicino e digli che non possiamo andare alla sua festa perché abbiamo una festa tutta nostra e un bambino tutto nostro! Oh, giorno felice!”

Così la visita fu annullata e in onore del nuovo bambino le campane della città, le sue armi, le sue trombe, i suoi abitanti, grandi e piccoli, non ebbero riposo per una settimana perché fu uno scampanare e sparare e squillare e un far esplodere fuochi d’artificio e un festeggiare e gioire e stare allegri come non si era mai visto prima.

Trascorsero un po’ di anni e siccome il figlio del re e la figlia del suo vicino crescevano e prosperavano, i due sovrani si accordarono perché si sposassero quando fossero grandi abbastanza; con molte firme sui documenti e molti accordi, e scuotimento di sagge teste e stropicciar di barbe grigie, l’accordo fu concluso, firmato e sigillato e poi depositato in attesa della sua applicazione. E passò anche questo perché appena il principe e la principessa ebbero diciotto anni, i re concordarono che era il momento delle nozze; il principe viaggiò fino al regno vicino per raggiungere la fidanzata e lì la sposò con grande e rinnovata gioia.

Adesso devo dirvi che la vecchia che aveva venduto la collana al re era stata chiamata per fare da balia al giovane principe, e sebbene amasse il proprio incarico e fosse una serva molto fedele, non poté fare a meno di parlarne solo un po’ e così, via via, si cominciò a mormorare che vi fosse qualcosa di magico nella nascita del principe; le chiacchiere naturalmente in poco tempo giunsero alle orecchie dei genitori della principessa. Siccome stava per diventare la moglie del principe, sua madre (che era curiosa come lo sono molte persone) disse alla figlia alla vigilia della cerimonia:

“Rammenta che per prima cosa devi scoprire che cosa sia questa storia sul principe. E per farlo non devi dirgli una parola finché lui non ti chiederà perché stai in silenzio; allora dovrai chiedergli la verità sulla sua nascita magica e non dovrai parlargli finché non te l’avrà detta.”

La principessa promise che avrebbe seguito il consiglio della madre.

Perciò quando furono sposati e il principe parlava alla sua sposa, lei non gli rispondeva. Egli non poteva immaginare quale fosse il motivo, ma persino sulla sua precedente casa non pronunciava una parola. Alla fine le chiese perché non parlasse e allora lei disse:

“Dimmi il segreto della tua nascita.”

Allora il principe si rattristò molto e si dispiacque e, sebbene lei insistesse molto, lui non glielo diceva, ma rispondeva sempre:

“Se te lo dicessi, ti pentiresti di avermelo chiesto.”

Vissero insieme per vari mesi e non fu per entrambi un periodo così felice come sarebbe dovuto essere perché il segreto rimaneva segreto e si frapponeva come una nuvola tra il sole e la terra, rendendo grigio e triste ciò che doveva essere lieto.

Infine il principe non poté sopportarlo più così un giorno disse alla moglie: “A mezzanotte ti dirò il mio segreto, se lo vorrai; ma te ne pentirai per tutta la vita.” La principessa fu felicissima di esserci riuscita e non badò all’avvertimento.

Quella notte il principe ordinò che un po’ prima di mezzanotte fossero pronti i cavalli per lui e per la principessa. La mise in sella su uno e montò sull’altro e cavalcarono insieme fino al fiume, nel posto in cui la vecchia aveva trovato per la prima volta il serpente nel vaso di ottone. Allora il principe tirò le redini e disse tristemente: “Insisti ancora perché ti dica il mio segreto?” e la principessa rispose: “Sì.” “Se lo faccio,” disse il principe, “ricordati che te ne pentirai per tutta la vita.” Ma la principessa rispose solo: “Dimmi!”

“Allora” disse il principe “sappi che sono il figlio del re di un paese lontano, ma un incantesimo mi ha trasformato in un serpente.”

La parola “serpente” gli era appena uscita dalle labbra che scomparve e la principessa sentì un fruscio e vide un’increspatura sull’acqua; nella tremula luce lunare intravide un serpente che nuotava presso la riva. Ben presto sparì e lei rimase sola. Invano attese con il batticuore che accadesse qualcosa e che il principe tornasse da lei. Non accadde nulla e non venne nessuno; solo il vento mormorava tra gli alberi sulla riva del fiume e gli uccelli notturni gridavano, lo sciacallo ululava in lontananza e il fiume scorreva nero e silenzioso sotto di lei.

La trovarono la mattina che piangeva scarmigliata sulla riva del fiume: non seppero da lei o da nessun altro una sola parola sul destino del principe. Secondo il suo desiderio costruirono sulla riva del fiume una casetta di pietra nera e lì visse in lutto, con pochi servitori e guardie a vegliare su di lei.

Trascorse molto, molto tempo e ancora la principessa viveva nel lutto per il principe; non vedeva nessuno e non andava mai via dalla casa sulla riva del fiume e dal giardino la circondava. Una mattina, quando si svegliò, si accorse di una macchia di fango fresco sul tappeto. Mandò a chiamare le guardie, che sorvegliavano la casa giorno e notte, e chiese loro chi fosse entrato nella stanza mentre lei dormiva. Loro affermarono che nessuno sarebbe potuto entrare perché loro facevano la guardia così attentamente che nemmeno un uccello poteva volare senza che lo sapessero, ma nessuno di loro poté spiegare come fosse arrivato lì il fango. Il mattino seguente, di nuovo, la principessa trovò un’altra macchia di fango fresco e interrogò di nuovo tutti con cura, ma nessuno seppe dirle da dove venisse il fango. La terza notte la principessa decise di restare sveglia lei stessa e fare la guardia; per paura di addormentarsi, si tagliò le dita con un temperino e mise il sale sulle ferite così che il dolore la tenesse sveglia. Così giacque sveglia e a mezzanotte vide un serpente che strisciava sul pavimento con in bocca un po’ di fango della riva del fiume; quando fu vicino al letto, sollevò la testa sporca di fango e la sgocciolò sulle lenzuola. La principessa era molto spaventata, ma cercò di controllare la paura e chiese:

“Chi sei tu e che cosa fai qui?”

“Sono il principe, tuo marito, e sono venuto a farti visita.”

Allora la principessa cominciò a piangere e il serpente proseguì:

“Ahimè, non ti avevo detto che se ti avessi rivelato il mio segreto te ne saresti pentita? E non sei pentita?”

La povera principessa esclamò: “Certo che mi sono pentita, e mi pentirò per tutta la vita! Non c’è niente che possa fare?”

E il serpente rispose:

“Sì, una cosa c’è, se oserai farla.”

“Devi solo dirmelo,” disse la principessa “e io farò qualsiasi cosa!”

Il serpente rispose: “Allora una certa notte dovrai mettere una grossa scodella di latte e di zucchero in ciascuno dei quattro angoli di questa stanza. Tutti i serpenti del fiume verranno a bere il latte e quello che aprirà la strada sarà la regina dei serpenti. Devi stare in attesa di lei sulla porta e dire: ‘Oh, Regina dei Serpenti, restituiscimi mio marito!’ e forse lei lo farà. Ma se avrai paura e non la fermerai, non mi vedrai di nuovo.” E scivolò via.

La notte della quale il serpente gli aveva parlato, la principessa prese quattro grosse scodelle di latte e zucchero e le mise una in ogni angolo della stanza e rimase in attesa sulla soglia. A mezzanotte ci fu un gran sibilare e frusciare dalla parte del fiume e subito il terreno sembrò prendere vita con le orribili forme striscianti dei serpenti, i cui occhi luccicavano e le lingue saettavano mentre si muovevano in direzione della casa della principessa. Avanti a tutti tra di loro c’era una grossa e repellente creatura coperta di scaglie che guidava la paurosa processione. Le guardie furono così spaventate che corsero via tutte, ma la principessa rimase sulla soglia, bianca come un cadavere, e con le mani serrate forte per timore di gridare o svenire e sbagliare a compiere la sua parte. Quando si fecero più vicini e la videro in attesa, tutti i serpenti sollevarono le orribili teste e le fecero ondeggiare avanti e indietro e la guardarono con i loro lucenti occhi malvagi, mentre i loro respiri sembravano avvelenare l’aria. La principessa rimaneva immobile e quando il serpente alla testa fu a pochi passi da lei, gridò: “Oh, Regina dei Serpenti, restituiscimi mio marito!” Allora tutta quella massa di serpenti fruscianti e sibilanti sembrò che si sussurrassero l’uno con l’altro ‘suo marito? suo marito?’ Ma la regina dei serpenti si mosse finché la sua testa fu quasi all’altezza del viso della principessa e i suoi occhi sembrarono emanare fiamme. E la principessa, immobile sulla soglia, non si mosse e di nuovo esclamò: “Oh, Regina dei Serpenti, Regina dei Serpenti, restituiscimi mio marito!” Allora la regina dei serpenti rispose: =Domani, lo riavrai… domani!” quando ebbe sentito queste parole e seppe di avercela fatta, la principessa si mosse barcollando dalla porta e cadde svenuta sul letto. Come in un sogno, vide la stanza piena di serpenti, tutti che si spingevano e bisticciavano per le tazze di latte finché le ebbero finite. Poi se ne andarono.

La mattina la principessa si alzò presto, gettò l’abito da lutto che aveva indossato per cinque anni e prese indumenti allegri e bellissimi. Pulì a fondo la casa, l’adornò di ghirlande e di mazzolini di fiori profumati e felci, come se si stesse preparando per le nozze. Quando scese la notte, illuminò il bosco e il giardino con lanterne, apparecchiò la tavola per un banchetto e accese in casa un migliaio di candele di cera. Poi attese il marito, non sapendo con quale aspetto sarebbe apparso. A mezzanotte il principe giunse dal fiume a grandi passi, ridendo, ma con le lacrime agli occhi; lei gli corse incontro e gli si gettò tra le braccia, piangendo e ridendo nel medesimo tempo.

Così il principe tornò a casa e il giorno seguente tornarono a palazzo e il vecchio re pianse di gioia, vedendoli. Dopo un lungo silenzio le campane furono fatte di nuovo suonare, le armi sparare e le trombe squillare e ci fu un banchetto con tanta contentezza.

La vecchia, che era stata balia del principe, divenne la balia anche dei suoi bambini… infine fu chiamata così, sebbene fosse troppo vecchia per fare qualsiasi altra cosa che amarli. Eppure pensava di essere ancora utile e sapere ciò la rendeva felice. E felici davvero furono il principe e la principessa, che a tempo debito divennero re e regina, e vissero e governarono a lungo e in prosperità.

Fiaba della città di Firozpur ( o Ferozepur) nella regione indiana del Punjab, tradotta dal maggiore Campbell.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)