Hans, the Mermaid's Son

(MP3-MB;24'33'')

In a village there once lived a smith called Basmus, who was in a very poor way. He was still a young man, and a strong handsome fellow to boot, but he had many little children and there was little to be earned by his trade. He was, however, a diligent and hard-working man, and when he had no work in the smithy he was out at sea fishing, or gathering wreckage on the shore.

It happened one time that he had gone out to fish in good weather, all alone in a little boat, but he did not come home that day, nor the following one, so that all believed he had perished out at sea. On the third day, however, Basmus came to shore again and had his boat full of fish, so big and fat that no one had ever seen their like. There was nothing the matter with him, and he complained neither of hunger or thirst. He had got into a fog, he said, and could not find land again. What he did not tell, however, was where he had been all the time; that only came out six years later, when people got to know that he had been caught by a mermaid out on the deep sea, and had been her guest during the three days that he was missing. From that time forth he went out no more to fish; nor, indeed, did he require to do so, for whenever he went down to the shore it never failed that some wreckage was washed up, and in it all kinds of valuable things. In those days everyone took what they found and got leave to keep it, so that the smith grew more prosperous day by day.

When seven years had passed since the smith went out to sea, it happened one morning, as he stood in the smithy, mending a plough, that a handsome young lad came in to him and said, 'Good-day, father; my mother the mermaid sends her greetings, and says that she has had me for six years now, and you can keep me for as long.'

He was a strange enough boy to be six years old, for he looked as if he were eighteen, and was even bigger and stronger than lads commonly are at that age.

'Will you have a bite of bread?' said the smith.

'Oh, yes,' said Hans, for that was his name.

The smith then told his wife to cut a piece of bread for him. She did so, and the boy swallowed it at one mouthful and went out again to the smithy to his father.

'Have you got all you can eat?' said the smith.

'No,' said Hans, 'that was just a little bit.'

The smith went into the house and took a whole loaf, which he cut into two slices and put butter and cheese between them, and this he gave to Hans. In a while the boy came out to the smithy again.

'Well, have you got as much as you can eat?' said the smith. 'No, not nearly,' said Hans; 'I must try to find a better place than this, for I can see that I shall never get my fill here.'

Hans wished to set off at once, as soon as his father would make a staff for him of such a kind as he wanted.

'It must be of iron,' said he, 'and one that can hold out.'

The smith brought him an iron rod as thick as an ordinary staff, but Hans took it and twisted it round his finger, so that wouldn't do. Then the smith came dragging one as thick as a waggon-pole, but Hans bent it over his knee and broke it like a straw. The smith then had to collect all the iron he had, and Hans held it while his father forged for him a staff, which was heavier than the anvil. When Hans had got this he said, 'Many thanks, father; now I have got my inheritance.' With this he set off into the country, and the smith was very pleased to be rid of that son, before he ate him out of house and home.

Hans first arrived at a large estate, and it so happened that the squire himself was standing outside the farmyard.

'Where are you going?' said the squire.

'I am looking for a place,' said Hans, 'where they have need of strong fellows, and can give them plenty to eat.'

'Well,' said the squire, 'I generally have twenty-four men at this time of the year, but I have only twelve just now, so I can easily take you on.'

'Very well,' said Hans, 'I shall easily do twelve men's work, but then I must also have as much to eat as the twelve would.'

All this was agreed to, and the squire took Hans into the kitchen, and told the servant girls that the new man was to have as much food as the other twelve. It was arranged that he should have a pot to himself, and he could then use the ladle to take his food with.

It was in the evening that Hans arrived there, so he did nothing more that day than eat his supper—a big pot of buck-wheat porridge, which he cleaned to the bottom and was then so far satisfied that he said he could sleep on that, so he went off to bed. He slept both well and long, and all the rest were up and at their work while he was still sleeping soundly. The squire was also on foot, for he was curious to see how the new man would behave who was both to eat and work for twelve.

But as yet there was no Hans to be seen, and the sun was already high in the heavens, so the squire himself went and called on him.

'Get up, Hans,' he cried; 'you are sleeping too long.'

Hans woke up and rubbed his eyes. 'Yes, that's true,' he said, 'I must get up and have my breakfast.'

So he rose and dressed himself, and went into the kitchen, where he got his pot of porridge; he swallowed all of this, and then asked what work he was to have.

He was to thresh that day, said the squire; the other twelve men were already busy at it. There were twelve threshing-floors, and the twelve men were at work on six of them—two on each. Hans must thresh by himself all that was lying upon the other six floors. He went out to the barn and got hold of a flail. Then he looked to see how the others did it and did the same, but at the first stroke he smashed the flail in pieces. There were several flails hanging there, and Hans took the one after the other, but they all went the same way, every one flying in splinters at the first stroke. He then looked round for something else to work with, and found a pair of strong beams lying near. Next he caught sight of a nailed up on the barn-door. With the beams he made a flail, using the skin to tie them together. The one beam he used as a handle, and the other to strike with, and now that was all right. But the barn was too low, there was no room to swing the flail, and the floors were too small. Hans, however, found a remedy for this—he simply lifted the whole roof off the barn, and set it down in the field beside. He then emptied down all the corn that he could lay his hands on and threshed away. He went through one lot after another, and it was all the same to him what he got hold of, so before midday he had threshed all the squire's grain, his rye and wheat and barley and oats, all mixed through each other. When he was finished with this, he lifted the roof up on the barn again, like setting a lid on a box, and went in and told the squire that the job was done.

The squire opened his eyes at this announcement; and came out to see if it was really true. It was true, sure enough, but he was scarcely delighted with the mixed grain that he got from all his crops. However, when he saw the flail that Hans had used, and learned how he had made room for himself to swing it, he was so afraid of the strong fellow, that he dared not say anything, except that it was a good thing he had got it threshed; but it had still to be cleaned.

'What does that mean?' asked Hans.

It was explained to him that the corn and the chaff had to be separated; as yet both were lying in one heap, right up to the roof. Hans began to take up a little and sift it in his hands, but he soon saw that this would never do. He soon thought of a plan, however; he opened both barn-doors, and then lay down at one end and blew, so that all the chaff flew out and lay like a sand-bank at the other end of the barn, and the grain was as clean as it could be. Then he reported to the squire that that job also was done. The squire said that that was well; there was nothing more for him to do that day. Off went Hans to the kitchen, and got as much as he could eat; then he went and took a midday nap which lasted till supper-time.

Meanwhile the squire was quite miserable, and made his moan to his wife, saying that she must help him to find some means to getting rid of this strong fellow, for he durst not give him his leave. She sent for the steward, and it was arranged that next day all the men should go to the forest for fire-wood, and that they should make a bargain among them, that the one who came home last with his load should be hanged. They thought they could easily manage that it would be Hans who would lose his life, for the others would be early on the road, while Hans would certainly oversleep himself. In the evening, therefore, the men sat and talked together, saying that next morning they must set out early to the forest, and as they had a hard day's work and a long journey before them, they would, for their amusement, make a compact, that whichever of them came home last with his load should lose his life on the gallows. So Hans had no objections to make.

Long before the sun was up next morning, all the twelve men were on foot. They took all the best horses and carts, and drove off to the forest. Hans, however, lay and slept on, and the squire said, 'Just let him lie.'

At last, Hans thought it was time to have his breakfast, so he got up and put on his clothes. He took plenty of time to his breakfast, and then went out to get his horse and cart ready. The others had taken everything that was any good, so that he had a difficulty in scraping together four wheels of different sizes and fixing them to an old cart, and he could find no other horses than a pair of old hacks. He did not know where it lay, but he followed the track of the other carts, and in that way came to it all right. On coming to the gate leading into the forest, he was unfortunate enough to break it in pieces, so he took a huge stone that was lying on the field, seven ells long, and seven ells broad, and set this in the gap, then he went on and joined the others. These laughed at him heartily, for they had laboured as hard as they could since daybreak, and had helped each other to fell trees and put them on the carts, so that all of these were now loaded except one.

Hans got hold of a woodman's axe and proceeded to fell a tree, but he destroyed the edge and broke the shaft at the first blow. He therefore laid down the axe, put his arms round the tree, and pulled it up by the roots. This he threw upon his cart, and then another and another, and thus he went on while all the others forgot their work, and stood with open mouths, gazing at this strange woodcraft. All at once they began to hurry; the last cart was loaded, and they whipped up their horses, so as to be the first to arrive home.

When Hans had finished his work, he again put his old hacks into the cart, but they could not move it from the spot. He was annoyed at this, and took them out again, twisted a rope round the cart, and all the trees, lifted the whole affair on his back, and set off home, leading the horses behind him by the rein. When he reached the gate, he found the whole row of carts standing there, unable to get any further for the stone which lay in the gap.

'What!' said Hans, 'can twelve men not move that stone?' With that he lifted it and threw it out of the way, and went on with his burden on his back, and the horses behind him, and arrived at the farm long before any of the others. The squire was walking about there, looking and looking, for he was very curious to know what had happened. Finally, he caught sight of Hans coming along in this fashion, and was so frightened that he did not know what to do, but he shut the gate and put on the bar. When Hans reached the gate of the courtyard, he laid down the trees and hammered at it, but no one came to open it. He then took the trees and tossed them over the barn into the yard, and the cart after them, so that every wheel flew off in a different direction.

When the squire saw this, he thought to himself, 'The horses will come the same way if I don't open the door,' so he did this.

'Good day, master,' said Hans, and put the horses into the stable, and went into the kitchen, to get something to eat. At length the other men came home with their loads. When they came in, Hans said to them, 'Do you remember the bargain we made last night? Which of you is it that's going to be hanged?' 'Oh,' said they, 'that was only a joke; it didn't mean anything.' 'Oh well, it doesn't matter, 'said Hans, and there was no more about it.

The squire, however, and his wife and the steward, had much to say to each other about the terrible man they had got, and all were agreed that they must get rid of him in some way or other. The steward said that he would manage this all right. Next morning they were to clean the well, and they would use of that opportunity. They would get him down into the well, and then have a big mill-stone ready to throw down on top of him—that would settle him. After that they could just fill in the well, and then escape being at any expense for his funeral. Both the squire and his wife thought this a splendid idea, and went about rejoicing at the thought that now they would get rid of Hans.

But Hans was hard to kill, as we shall see. He slept long next morning, as he always did, and finally, as he would not waken by himself, the squire had to go and call him. 'Get up, Hans, you are sleeping too long,' he cried. Hans woke up and rubbed his eyes. 'That's so,' said he, 'I shall rise and have my breakfast.' He got up then and dressed himself, while the breakfast stood waiting for him. When he had finished the whole of this, he asked what he was to do that day. He was told to help the other men to clean out the well. That was all right, and he went out and found the other men waiting for him. To these he said that they could choose whichever task they liked - either to go down into the well and fill the buckets while he pulled them up, or pull them up, and he alone would go down to the bottom of the well. They answered that they would rather stay above-ground, as there would be no room for so many of them down in the well.

Hans therefore went down alone, and began to clean out the well, but the men had arranged how they were to act, and immediately each of them seized a stone from a heap of huge blocks, and threw them down above him, thinking to kill him with these. Hans, however, gave no more heed to this than to shout up to them, to keep the hens away from the well, for they were scraping gravel down on the top of him.

They then saw that they could not kill him with little stones, but they had still the big one left. The whole twelve of them set to work with poles and rollers and rolled the big mill-stone to the brink of the well. It was with the greatest difficulty that they got it thrown down there, and now they had no doubt that he had got all that he wanted. But the stone happened to fall so luckily that his head went right through the hole in the middle of the mill-stone, so that it sat round his neck like a priest's collar. At this, Hans would stay down no longer. He came out of the well, with the mill-stone round his neck, ad went straight to the squire and complained that the other men were trying to make a fool of him. He would not be their priest, he said; he had too little learning for that. Saying this, he bent down his head and shook the stone off, so that it crushed one of the squire's big toes.

The squire went limping in to his wife, and the steward was sent for. He was told that he must devise some plan for getting rid of this terrible person. The scheme he had devised before had been of no use, and now good counsel was scarce.

'Oh, no' said the steward, 'there are good enough ways yet. The squire can send him this evening to fish in Devilmoss Lake: he will never escape alive from there, for no one can go there by night for Old Eric.'

That was a grand idea, both the squire and his wife thought, and so he limped out again to Hans, and said that he would punish his men for having tried to make a fool of him. Meanwhile, Hans could do a little job where he would be free from these rascals. He should go out on the lake and fish there that night, and would then be free from all work on the following day.

'All right,' said Hans; 'I am well content with that, but I must have something with me to eat—a baking of bread, a cask of butter, a barrel of ale, and a keg of brandy. I can't do with less than that.'

The squire said that he could easily get all that, so Hans got all of these tied up together, hung them over his shoulder on his good staff, and tramped away to Devilmoss Lake.

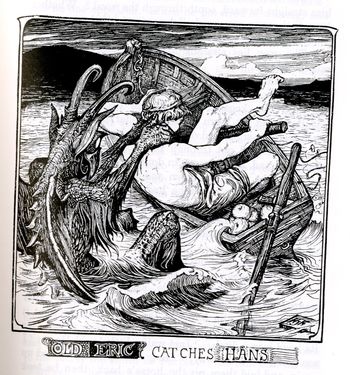

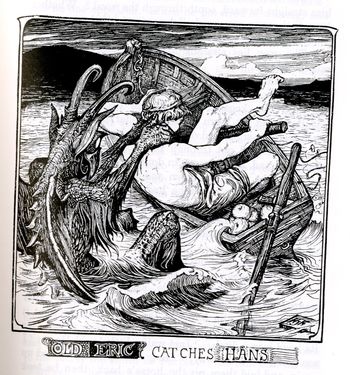

There he got into the boat, rowed out upon the lake, and got everything ready to fish. As he now lay out there in the middle of the lake, and it was pretty late in the evening, he thought he would have something to eat first, before starting to work. Just as he was at his busiest with this, Old Eric rose out of the lake, caught him by the cuff of the neck, whipped him out of the boat, and dragged him down to the bottom.

It was a lucky thing that Hans had his walking-stick with him that day, and had just time to catch hold of it when he felt Old Eric's claws in his neck, so when they got down to the bottom he said, 'Stop now, just wait a little; here is solid ground.' With that he caught Old Eric by the back of the neck with one hand, and hammered away on his back with the staff, till he beat him out as flat as a pancake. Old Eric then began to lament and howl, begging him just to let him go, and he would never come back to the lake again.

'No, my good fellow,' said Hans, 'you won't get off until you promise to bring all the fish in the lake up to the squire's courtyard, before to-morrow morning.'

Old Eric eagerly promised this, if Hans would only let him go; so Hans rowed ashore, ate up the rest of his provisions, and went home to bed.

Next morning, when the squire rose and opened his front door, the fish came tumbling into the porch, and the whole yard was crammed full of them. He ran in again to his wife, for he could never devise anything himself, and said to her, 'What shall we do with him now? Old Eric hasn't taken him. I am certain that all the fish are out of the lake, for the yard is just filled with them.'

'Yes, that's a bad business,' said she; 'you must see if you can't get him sent to Purgatory, to demand tribute.' The squire therefore made his way to the men's quarters, to speak to Hans, and it took him all his time to push his way along the walls, under the eaves, on account of the fish that filled the yard. He thanked Hans for having fished so well, and said that now he had an errand for him, which he could only give to a trusty servant, and that was to journey to Purgatory, and demand three years tribute, which, he said, was owing to him from that quarter.

'Willingly,' said Hans; 'but what road do I go, to get there?'

The squire stood, and did not know what to say, and had first to go in to his wife to ask her.

'Oh, what a fool you are!' said she, 'can't you direct him straight forward, south through the wood? Whether he gets there or not, we shall be quit of him.'

Out goes the squire again to Hans.

'The way lies straight forward, south through the wood,' said he.

Hans then must have his provisions for the journey; two bakings of bread, two casks of butter, two barrels of ale, and two kegs of brandy. He tied all these up together, and got them on his shoulder hanging on his good walking-stick, and off he tramped southward.

After he had got through the wood, there was more than one road, and he was in doubt which of them was the right one, so he sat down and opened up his bundle of provisions. He found he had left his knife at home, but by good chance, there was a plough lying close at hand, so he took the coulter of this to cut the bread with. As he sat there and took his bite, a man came riding past him.

'Where are you from?' said Hans.

'From Purgatory,' said the man.

'Then stop and wait a little,' said Hans; but the man was in a hurry, and would not stop, so Hans ran after him and caught the horse by the tail. This brought it down on its hind legs, and the man went flying over its head into a ditch. 'Just wait a little,' said Hans; 'I am going the same way.' He got his provisions tied up again, and laid them on the horse's back; then he took hold of the reins and said to the man, 'We two can go along together on foot.'

As they went on their way Hans told the stranger both about the errand he had on hand and the fun he had had with Old Eric. The other said but little but he was well acquainted with the way, and it was no long time before they arrived at the gate. There both horse and rider disappeared, and Hans was left alone outside. 'They will come and let me in presently,' he thought to himself; but no one came. He hammered at the gate; still no one appeared. Then he got tired of waiting, and smashed at the gate with his staff until he knocked it in pieces and got inside. A whole troop of little demons came down upon him and asked what he wanted. His master's compliments, said Hans, and he wanted three years' tribute. At this they howled at him, and were about to lay hold of him and drag him off; but when they had got some raps from his walking-stick they let go again, howled still louder than before, and ran in to Old Eric, who was still in bed, after his adventure in the lake. They told him that a messenger had come from the squire at Devilmoss to demand three years' tribute. He had knocked the gate to pieces and bruised their arms and legs with his iron staff. 'Give him three years'! give him ten!' shouted Old Eric, 'only don't let him come near me.' So all the little demons came dragging so much silver and gold that it was something awful. Hans filled his bundle with gold and silver coins, put it on his neck, and tramped back to his master, who was scared beyond all measure at seeing him again.

But Hans was also tired of service now. Of all the gold and silver he brought with him he let the squire keep one half, and he was glad enough, both for the money and at getting rid of Hans. The other half he took home to his father the smith in Furreby. To him also he said, 'Farewell;' he was now tired of living on shore among mortal men, and preferred to go home again to his mother. Since that time no one has ever seen Hans, the Mermaid's son.

Translated from the Danish.

Hans, il figlio della sirena

C’era una volta in un villaggio un fabbro che si chiamava Basmus ed era assai povero. Era ancora giovane e per giunta forte e di bell’aspetto, ma aveva molti bambini che erano troppo piccoli per poter essere istruiti nel suo mestiere. In ogni modo era un uomo diligente e laborioso e, quando non aveva lavoro nella fucina, era fuori a pescare o a raccogliere relitti sulla spiaggia.

Una volta accadde che fosse uscito a pescare con il bel tempo, tutto solo in una barchetta, ma che quel giorno non fosse tornato a casa, neppure il giorno seguente, così tutti cedettero che fosse morto in mare. In ogni modo il terzo giorno Basmus tornò di nuovo sulla spiaggia e con la barca piena di pesci, così grandi e grossi come nessuno li aveva mai visti prima. Non si ottenne nulla da lui, e non si lamentò di aver sofferto la fame o la sete. Era finito in mezzo alla nebbia, disse, e non riusciva a trovare di nuovo la terra. Ciò che non disse, in ogni modo, fu dove fosse stato tutto il tempo; cosa che venne fuori solo sei anni più tardi, quando la gente scoprì che era stato catturato da una sirena in fondo al mare ed era stato suo ospite in quei tre giorni durante i quali era stato dato per disperso. Da quella volta in poi non andò più a pescare; non che avesse davvero bisogno di farlo, perché ogni volta in cui scendeva alla spiaggia, non mancava mai che vi fosse finito qualche relitto e ogni altro genere di cose di valore. In quei giorni ciascuno prendeva ciò che trovava e lo poteva tenere, cosicché di giorno in giorno il fabbro divenne sempre più agiato.

Quando furono trascorsi sette anni senza che il fabbro andasse per mare, una mattina accadde, mentre si trovava nella fucina a riparare un aratro, che un bel ragazzino andasse da lui e gli dicesse. “Buongiorno, padre; mia madre la sirena vi manda i suoi saluti e dice che mi ha tenuto fino ad ora per sei anni e che potete tenermi voi per altrettanto tempo.”

Era un bambino abbastanza strano per avere sei anni perché sembrava piuttosto ne avesse otto ed era più grosso e più robusto di quanto normalmente sia un bambino a quel’età.

“Vorresti un tozzo di pane?” disse il fabbro.

”Oh, sì.” rispose Hans, perché quello era il suo nome.

Il fabbro allora disse alla moglie di tagliare un pezzo di pane per lui. Glielo diede e il ragazzo lo ingoiò in un sol boccone poi andò di nuovo nella fucina con suo padre.

”Hai mangiato abbastanza?” disse il fabbro.

Hans disse: “No, è stato solo un bocconcino.”

Il fabbro tornò in casa, prese una pagnotta intera, che tagliò in due parti, mettendovi in mezzo burro e formaggio, e la diede a Hans. In un attimo il ragazzo tornò di nuovo nella fucina.

”Ebbene, adesso hai mangiato abbastanza?” disse il fabbro.

”Neanche un po’,” disse Hans; “devo trovare un posto migliore di questo perché vedo bene che qui non mi sazierò mai.”

Hans voleva andarsene subito, appena suo padre avesse fatto per lui un bastone proprio come lo voleva.

”Deve essere di ferro,” disse, “e che si possa allungare.”

Il fabbro gli portò un bastone di ferro pesante come un qualsiasi bastone, ma Hans lo prese e lo attorcigliò intorno alle dita, come non si potrebbe fare. Allora il fabbro arrivò trascinandone uno grosso come una sbarra di vagone, ma Hans lo piegò sul ginocchio e lo spezzò come una pagliuzza. Allora il fabbro raccolse tutto il ferro che aveva e Hans aspettò mentre suo padre forgiava con esso un bastone che era più pesante dell’incudine. Quando Hans l’ebbe, preso, disse: “Ti ringrazio molto, padre; adesso ho ottenuto la mia eredità.” E con ciò se ne andò per il paese e il fabbro fu assai contento di essersi sbarazzato di un figlio simile, prima che gli facesse fuori la casa.

Dapprima Hans arrivò in una vasta tenuta e il caso volle che il gentiluomo stesso si trovasse fuori in cortile.

”Dove stai andando?” chiese il gentiluomo.

”Sto cercando un posto in cui abbiano bisogno di persone forti e possano dal loro da mangiare in abbondanza.”

Il gentiluomo disse: “Ebbene, io di solito in questo periodo dell’anno ho ventiquattro uomini, ma proprio adesso ne ho solo dodici, così posso assumerti senza problemi.”

Hans disse: “Benissimo, svolgerò facilmente il lavoro di dodici uomini, ma allora dovrò avere abbastanza da mangiare come lo avrebbero dodici.”

Accordatisi su ciò, il gentiluomo condusse Hans in cucina e disse alla sguattera che lui era il nuovo assunto che doveva avere tanto cibo quanto gli altri dodici. Fu deciso che avrebbe avuto una pentola per sé e che avrebbe usato un mestolo per prenderne il cibo.

Era sera quando Hans arrivò là, così non ebbe altro da fare che mangiare la propria cena – una grossa pentola di pappa d’avena con il montone, che ripulì fino in fondo e ne fu così soddisfatto che disse che sarebbe andato a dormire, così andò a letto. Dormì saporitamente e tutti erano già in piedi e al lavoro mentre lui stava ancora russando sonoramente. Anche il gentiluomo era alzato perché era curioso di vedere se il nuovo assunto si sarebbe comportato davvero come uno che mangia e lavora per dodici.

Ma fino a quel momento Hans non si era ancora visto e il sole era già piuttosto alto nel cielo, così il gentiluomo in persona andò a chiamarlo.

”Tirati su, Hans,” gridò, “stai dormendo troppo.”

Hans si svegliò e si stropicciò gli occhi. “Sì, è vero,” disse, “devo alzarmi e fare colazione.

Così si alzò, si vestì e andò in cucina, dove prese la sua pentola di pappa d’avena; la trangugiò tutta e poi chiese che lavoro dovesse fare.

Il gentiluomo gli disse che quel giorno avrebbe dovuto trebbiare; gli altri dodici uomini erano già occupati a farlo. C’erano dodici aie e i dodici uomini si occupavano di sei di esse, due per ciascuno. Hans doveva trebbiare da solo tutto ciò che cresceva nelle altre sei aie. Andò nel fienile e prese un correggiato. (1) Poi guardò per vedere come facessero gli altri e imitarli, ma al primo colpo mandò in pezzi il correggiato. C’erano appesi là vari correggiati, e Hans li prese l’uno dopo l’altro, ma fecero tutti la medesima fine, ognuno finiva in pezzi al primo colpo. Allora si guardò attorno in cerca di qualcosa con cui lavorare e trovò lì vicino un paio di robuste travi. Poi si accorse di una pelle di cavallo inchiodata sulla porta del fienile. Fece così un correggiato con le travi, usando la pelle per legarle insieme. Usava una trave come manico e l’altra per battere, e così fu tutto sistemato. Ma il fienile era troppo basso, non c’era una stanza in cui far roteare il correggiato, e il pavimento era troppo piccolo. Tuttavia Hans trovò una soluzione anche a questo problema; semplicemente scoperchiò il fienile e lo mise accanto al campo. Poi versò tutto il mais che poteva tenere in mano e proseguì con la trebbiatura. Attraversò un appezzamento dopo l’altro e per lui non faceva differenza che cosa raccogliesse, così prima di mezzogiorno aveva trebbiato tutti i cereali del gentiluomo, la segale, il grano, l’orzo e l’avena, e li aveva mischiati tutti l’uno con l’altro. Quando ebbe finito, mise di nuovo il tetto sul fienile, come se chiudesse il coperchio di una scatola, e andò a dire al gentiluomo che il lavoro era finito.

Il gentiluomo spalancò gli occhi a una tale notizia e andò a vedere se fosse proprio vera. Era vera, effettivamente, ma non fu molto contento del miscuglio di cereali che aveva fatto di tutti i suoi raccolti. In ogni modo, quando vide il correggiato che Hans aveva usato, e appreso in quale modo avesse modificato il locale per rotearlo, ebbe così paura del giovane forzuto che non osò dirgli nulla, tranne che era stata una buona cosa che avesse trebbiato, ma doveva essere ripulito.

”Che significa?” chiese Hans.

Gli fu spiegato che il grano e la pula dovevano essere separati, visto che erano in un solo mucchio, che quasi giungeva al soffitto. Hans cominciò a prenderne un po’ e a setacciarlo con le mani, ma si accorse ben presto che non ce l’avrebbe fatta. Comunque escogitò subito un piano; aprì entrambe le porte del fienile, si sdraiò all’estremità di una e soffiò, così che tutta la pula volò via e si depose come un banco di sabbia all’altra estremità del fienile, e il grano fu pulito come doveva essere. Allora riferì al gentiluomo che anche quel lavoro era fatto. il gentiluomo disse che andava bene, per quel giorno non aveva da dargli altro da fare. Hans andò in cucina e mangiò più che poté, poi fece un sonnellino pomeridiano che durò fino all’ora di cena.

Nel frattempo il gentiluomo era piuttosto infelice e andò a lamentarsi con la moglie, dicendo che doveva aiutarlo a trovare un modo per liberarsi del giovane forzuto perché non osava licenziarlo. La donna chiamò il fattore e fu stabilito che il giorno seguente tutti gli uomini sarebbe andati nella foresta a procurare legna da ardere e che avrebbero fatto un patto tra di loro: l’ultimo che fosse giunto a casa con il proprio carico, sarebbe stato impiccato. Pensavano che sarebbero riusciti facilmente a fare in modo che fosse Hans a perdere la vita, perché gli altri si sarebbero messi presto in cammino mentre Hans certamente avrebbe continuato a dormire. Perciò la sera gli uomini sedettero insieme a parlare, dicendo che la mattina seguente sarebbero dovuti andare di buon’ora nella foresta e che, siccome avevano davanti un giorno di duro lavoro e un lungo viaggio, per divertirsi avrebbero fatto l’accordo che chiunque di loro fosse tornato a casa per ultimo con il proprio carico avrebbe perso la vita sulla forca. Hans non fece obiezioni.

Assai prima che il sole si alzasse il mattino seguente, tutti e dodici gli uomini erano alzati. Presero i migliori cavalli e carri e andarono verso la foresta. Hans, tuttavia, rimase a dormire e il gentiluomo disse. “Lasciamolo proprio coricato.”

Infine Hans ritenne che fosse il momento di fare colazione, così si alzò e indossò gli abiti. Si prese parecchio tempo per la colazione e poi uscì a preparare il cavallo e il carro. Gli altri avevano preso tutto ciò che c’era di buono cosi che lui ebbe difficoltà a mettere insieme quattro ruote di misure diverse e a fissarle a un vecchio carro, e non poté trovare altri cavalli che un paio di vecchi ronzini. Non conosceva la direzione, ma seguì le tracce degli altri carri e in tal modo gli andò tutto bene. Passando per il cancello che conduceva nella foresta, fu abbastanza sfortunato da farlo a pezzi, così prese un’enorme pietra che si trovava in un campo, lunga e larga sette braccia, e la mise nel varco, poi proseguì e raggiunse gli altri. Là risero di cuore di lui perché avevano lavorato più alacremente che avevano potuto fino al tramonto e si erano aiutati gli uni con gli altri ad abbattere gli alberi e a metterli sui carri, così che a quel punto erano tutti carichi tranne uno.

Hans impugnò una vecchia ascia e cominciò a tagliare un albero, ma distrusse la lama e ruppe il manico al primo colpo. Quindi gettò via l’ascia, abbracciò il tronco e lo sradicò. Lo gettò nel carro, e poi, un altro, e un altro ancora, e andò avanti così mentre tutti gli altri dimenticavano il lavoro e restavano a bocca aperta, osservando questa sua strana abilità di boscaiolo. All’improvviso cominciarono ad affrettarsi; l’ultimo carro fu caricato e frustarono i cavalli così da essere i primi ad arrivare a casa.

Quando Hans ebbe terminato il lavoro, attaccò di nuovo al carro i vecchi ronzini, ma essi non volevano muoversi da quel punto. Infastidito da ciò, li tolse di nuovo, avvolse una fune intorno al carro, con tutti gli alberi, si caricò il tutto sulle spalle e tornò a casa, portandosi dietro i cavalli per le redini. Quando raggiunse il cancello, trovò l’intera fila di carri che stavano lì, incapaci di andare avanti a causa della pietra posta nel varco.

”Ma come!” disse Hans, “Dodici uomini non possono muovere quella pietra?” E detto ciò, la sollevò e la gettò via dalla strada, poi ripartì con il carico sulle spalle e i cavalli dietro di sé, arrivando alla fattoria assai prima degli altri. Il gentiluomo stava passeggiando, guardando e riguardando, perché era assai curioso di sapere che cosa sarebbe accaduto. Infine scorse Hans che veniva in tal modo ed ebbe così paura da non sapere che cosa fare, così chiuse il cancello e mise la sbarra. Quando Hans raggiunse il cancello del cortile, depose gli alberi e bussò con forza, ma nessuno veniva ad aprirgli. Allora prese gli alberi e li gettò oltre la sbarra nel cortile, con il carro appresso, cosicché ogni ruota schizzò in una direzione diversa.

Quando il gentiluomo vide ciò, pensò tra sé: “I cavalla subiranno la medesima sorte, se non aprirò la porta.” E così fece.

”Buongiorno, padrone,” disse Hans, e mise I cavalla nella stalla, poi andò in cucina a prendersi qualcosa da mangiare. Finalmente giunsero a casa gli altri uomini con i loro carichi. Quando entrarono, Hans disse loro: “Rammentate il patto che facemmo la scorsa notte? Chi di voi sta per essere impiccato?” Risposero: “Oh, era solo uno scherzo, non voleva dir nulla.” “Bene, non importa.” disse Hans e non se ne fece più nulla.

In ogni modo il signorotto, sua moglie e il fattore ebbero molto di cui parlare tra di loro riguardo il terribile individuo che avevano lì, e concordarono di doversi liberare di lui in un modo o nell’altro. Il fattore disse che avrebbe organizzato lui ben bene. Il mattino dovevano pulire il pozzo e avrebbero sfruttato l’occasione. Lo avrebbero gettato nel pozzo e poi avrebbero avuta pronta una grossa macina di mulino da gettare sopra di lui, che lo avrebbe sistemato. Dopo avrebbero solo dovuto riempire il pozzo e si sarebbero risparmiati la spesa del suo funerale. Sia il gentiluomo che la moglie pensarono fosse una splendida idea e se ne andarono rallegrandosi al pensiero che ora si sarebbero liberati di Hans.

Ma Hans aveva la pelle dura, come vedremo. Dormì fino al mattino seguente, come faceva sempre, e siccome non si sarebbe svegliato da solo, il gentiluomo dovette andare a chiamarlo. “Alzati, Hans, stai dormendo troppo.” Gridò. Hans si svegliò e si stropicciò gli occhi. “È vero,” disse, “Mi alzerò e farò colazione.” Allora si alzò e si vestì, mentre la colazione lo stava aspettando. Quando l’ebbe finita tutta, chiese che cosa dovesse fare quel giorno. Gli fu detto di aiutare gli altri uomini a pulire il pozzo. Era tutto a posto e così uscì e trovò gli altri uomini che lo stavano aspettando. Disse loro che avrebbero potuto scegliere qualsiasi compito preferissero – sia scendere nel pozzo e riempire i secchi mentre lui li tirava su oppure tirare su loro e lui da solo sarebbe sceso sul fondo del pozzo. Risposero che avrebbero preferito restare in superficie perché non ci sarebbe stato abbastanza spazio per così tanti di loro nel pozzo.

Quindi Hans scese solo e cominciò a pulire il pozzo, ma gli uomini si erano messi d’accordo su che cosa dovessero fare e subito alcuni di loro presero una pietra da un mucchio di grossi blocchi e la gettarono giù addosso a lui, pensando di ucciderlo con essa. In ogni modo Hans non vi badò se non per gridare loro di tenere le galline lontane dal pozzo perché gli stavano gettando in testa la ghiaia.

Allora videro che non sarebbero riusciti a ucciderlo con pietre piccole, ma che dovevano gettare la più grossa. Tutti e dodici lavorarono di pali e rulli e fecero rotolare la grossa macina da mulino fino all’orlo del pozzo. Fu con la più grande difficoltà che ve la gettarono giù e adesso non avevano più dubbi che avrebbe avuto ciò che si meritava. Ma per fortuna successe che la pietra cadesse in modo che la sua testa passò proprio per il buco in mezzo alla macina da mulino, così che rimase intorno al suo collo come il collare di un sacerdote. A questo punto Hans non rimase giù più a lungo. Venne fuori dal pozzo, con la macina da mulino intorno al collo, e andò difilato dal gentiluomo a lagnarsi che gli altri uomini stavano tentando di imbrogliarlo. Non sarebbe stato il loro sacerdote, disse; ne sapeva troppo poco. Così dicendo, chinò la testa e scosse via la pietra, che schiacciò un alluce del gentiluomo.

Il gentiluomo andò da sua moglie zoppicando e fu mandato a chiamare il fattore. Gli fu detto che doveva escogitare un piano diverso per sbarazzarsi di quel terribile individuo. Il progetto che aveva ideato prima non era stato utile e scarseggiavano i buoni suggerimenti.

Il fattore disse: “Oh, no, si sono ancora abbastanza scappatoie. Il padrone deve mandarlo stasera a pescare nel lago detto Palude del Diavolo: non ne uscirà vivo perché nessuno va là di notte per via del Vecchio Eric.”

Era un’idea geniale, lo pensavano sia il gentiluomo che sua moglie, e così zoppicò di nuovo da Hans e gli disse che avrebbe punito gli uomini per aver tentato di imbrogliarlo. Nel frattempo Hans avrebbe dovuto fare un lavoretto in un luogo in cui sarebbe stato libero da quelle canaglie. Quella notte sarebbe dovuto andare al lago a pescare e poi sarebbe stato libero dal lavoro per tutto il giorno seguente.

Hans disse: “D’accordo, ne sono assai soddisfatto, ma devo portare con me qualcosa da mangiare – un’infornata di pane, un barile di burro, una botte di birra e un barilotto di acquavite. Non possa farcela senza almeno queste cose.”

Il gentiluomo disse che avrebbe avuto tutto facilmente, così Hans legò tutto insieme, se lo mise in spalla con il suo fido bastone e s’incamminò verso il lago Palude del Diavolo.

Lì salì su una barca, remò nel lago e preparò tutto l’occorrente per pescare. Siccome adesso si trovava in mezzo al lago ed era sera piuttosto tardi, pensò che avrebbe mangiato qualcosa, prima di cominciare a lavorare. mentre era occupato così, il Vecchio Eric emerse dal lago, lo afferrò per il colletto, lo tirò via dalla barca e lo trascinò sul fondo.

Fu una fortuna che quel giorno Hans avesse avuto con sé il bastone da passeggio, ed ebbe appena il tempo di afferrarlo quando sentì sul collo gli artigli del Vecchio Eric, così quando arrivarono sul fondo, disse. “Adesso fermati, aspetta un po’; qui siamo sul terreno solido.” E con ciò afferrò il Vecchio Eric dietro il collo con una mano e picchiò col bastone finché l’ebbe appiattito come una tavola. Il Vecchio Eric allora cominciò a lamentarsi e a gemere, pregandolo di lasciarlo andare, e non sarebbe mai più tornato nel lago.

”No, vecchio mio,” disse Hans, “non te ne andrai finché non mi avrai promesso di portare tutto il pesce del lago nel cortile del padrone prima di domani mattina.”

Il Vecchio Eric promise con ardore, se solo Hans lo avesse lasciato andare; così Hans remò verso la spiaggia, mangiò la rimanenza delle provviste e andò a casa a dormire.

Il mattino seguente, quando il gentiluomo si alzò e aprì la porta davanti al cortile, il pesce ruzzolò nella veranda e l’intero cortile ne fu pieno zeppo. Corse di nuovo dentro da sua moglie, perché da solo non riusciva a pensare a niente, e le disse: “Che facciamo con lui adesso? Il Vecchio Eric non l’ha divorato. Sono certo che sono venuti fuori dal lago tutti i pesci perché il cortile ne è proprio pieno.”

”Già, brutto affare,” disse lei, “devi vedere se puoi mandarlo in Purgatorio a riscuotere il tributo.” Perciò il gentiluomo andò negli alloggi degli uomini, per parlare con Hans, e gli ci volle tutto il tempo per farsi strada verso le mura, sotto le grondaie, a causa del pesce che riempiva il cortile. Ringraziò Hans per avere pescato così bene e disse che adesso aveva un incarico per lui, che poteva dare solo a un servitore fidato, ed era un viaggio in Purgatorio, a chiedere tre anni di tributi i quali, gli disse, gli erano dovuti da quell’alloggio.

”Volentieri,” disse Hans, “ma quale strada dovrò seguire, per arrivare là?”

Il gentiluomo rimase lì su due piedi e non sapeva che cosa dire, prima dovette andare da sua moglie a chiedere.

”Oh, sei proprio uno sciocco!” disse lei, “non puoi mandarlo direttamente avanti, a sud attraverso il bosco? Che ci arrivi o no, ci saremo liberati di lui per un po’.”

Il gentiluomo tornò da Hans.

”La strada va dritta avanti, verso sud attraverso il bosco.” Disse.

Hans doveva avere provviste per il viaggio: due infornate di pane, due barili di burro, due botti di birra e due barilotti di acquavite. Li legò tutti insieme, se li appese sulle spalle al suo buon bastone da passeggio e si incamminò verso sud.

Dopo che ebbe attraversato il bosco, c’era più di una strada e lui non sapeva quale fosse quella giusta, così sedette e aprì il fagotto delle provviste. Scoprì di aver lasciato a casa il coltello, ma per fortuna c’era un aratro a portata di mano, così ne prese la lama per tagliare il pane. Mentre era seduto e ne mangiava un boccone, lo oltrepassò un uomo a cavallo.

”Da dove vieni?” disse Hans.

”Dal Purgatorio.” disse l’uomo.

”Allora fermata e aspetta un attimo.” disse Hans, ma l’uomo aveva fretta e non volle fermarsi, così Hans lo inseguì e afferrò il cavallo per la coda. Ciò lo fece piegare sulle zampe posteriori e l’uomo volò sopra la sua testa in un fossato. “Aspetta solo un attimo,” disse Hans, “Devo fare la medesima strada.” Legò di nuovo le provviste e le gettò sul dorso del cavallo, poi afferrò le redini e disse all’uomo: “Noi due andremo avanti insieme piedi.”

Mentre percorrevano la strada, Hans raccontò allo straniero sia il compito che gli era stato affidato sia come si fosse divertito con il Vecchio Eric. L’altro disse poco e niente, ma conosceva bene la strada e non ci volle molto prima che giungessero a un cancello. Allora sia il cavallo che il cavaliere sparirono e Hans rimase lì fuori da solo. “Verranno da me tra poco.” pensò fra sé, ma non venne nessuno. Picchiò sul cancello; ancora non apparve nessuno. Allora si stancò di aspettare e fracassò il cancello con il bastone finché lo ridusse in pezzi e entrò. Gli venne davanti un intero squadrone di piccoli demoni e chiese che cosa volesse. Portava gli omaggi del padrone, disse, e esigeva tre anni di tributi. A queste parole ulularono verso di lui e stavano per afferrarlo e trascinarlo, ma quando ebbero assaggiato alcuni colpi del suo bastone da passeggio, se ne andarono di nuovo, ululando più forte di prima, e corsero dal Vecchio Eric, che era ancora a letto dopo l’avventura del lago. Gli dissero che un messaggero veniva da parte del gentiluomo della Palude del Diavolo a chiedere tre anni di tributi. Aveva ridotto in pezzi il cancello e ammaccato loro braccia e gambe con il suo bastone d’acciaio.

”Dargli tre anni di tributi! Diamogliene dieci!” strillo il Vecchio Eric, “purché non mi venga vicino.” Così i piccoli demoni tornarono trascinando così tanto argento e oro che era qualcosa di enorme, Hans riempì il fagotto con le monete d’argento e d’oro, se lo mise in spalla e tornò a piedi dal padrone, che temeva più di ogni cosa di rivederlo.

Ma Hans si era stancato di stare a servizio. Lasciò che il gentiluomo prendesse la metà di tutto l’argento e l’oro che aveva portato con sé, e ne fu abbastanza contento, sia per le monete che per sbarazzarsi di Hans. L’altra metà la portò a casa a suo padre, il fabbro di Furreby. Gli disse anche: “Addio.”; a desso si era stancato di vivere sulla terra tra i mortali e preferiva tornare a casa da sua madre. Da quella volta nessuno ha mai più visto Hans, il figlio della sirena.

Traduzione dal danese

(1) Arnese per la battitura dei cereali e di altre piante da seme, formato da due bastoni, detti rispettivam. manfanile (quello più lungo che costituisce il manico) e vetta, uniti da una correggia di cuoio (gómbina). (dal vocabolario Treccani)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)