The Jackal, the Dove and the Panther

(MP3-9'42'')

There was once a dove who built a nice soft nest as a home for her three little ones. She was very proud of their beauty, and perhaps talked about them to her neighbours more than she need have done, till at last everybody for miles round knew where the three prettiest baby doves in the whole country-side were to be found.

One day a jackal who was prowling about in search of a dinner came by chance to the foot of the rock where the dove's nest was hidden away, and he suddenly bethought himself that if he could get nothing better he might manage to make a mouthful of one of the young doves. So he shouted as loud as he could, 'Ohe, ohe, mother dove.'

And the dove replied, trembling with fear, 'What do you want, sir?'

'One of your children,' said he; 'and if you don't throw it to me I will eat up you and the others as well.'

Now, the dove was nearly driven distracted at the jackal's words; but, in order to save the lives of the other two, she did at last throw the little one out of the nest. The jackal ate it up, and went home to sleep.

Meanwhile the mother dove sat on the edge of her nest, crying bitterly, when a heron, who was flying slowly past the rock, was filled with pity for her, and stopped to ask, 'What is the matter, you poor dove?'

And the dove answered, 'A jackal came by, and asked me to give him one of my little ones, and said that if I refused he would jump on my nest and eat us all up.'

But the heron replied, 'You should not have believed him. He could never have jumped so high. He only deceived you because he wanted something for supper.' And with these words the heron flew off.

He had hardly got out of sight when again the jackal came creeping slowly round the foot of the rock. And when he saw the dove he cried out a second time, 'Ohe, ohe, mother dove! give me one of your little ones, or I will jump on your nest and eat you all up.'

This time the dove knew better, and she answered boldly, 'Indeed, I shall do nothing of the sort,' though her heart beat wildly with fear when she saw the jackal preparing for a spring.

However, he only cut himself against the rock, and thought he had better stick to threats, so he started again with his old cry, 'Mother dove, mother dove! be quick and give me one of your little ones, or I will eat you all up.'

But the mother dove only answered as before, 'Indeed, I shall do nothing of the sort, for I know we are safely out of your reach.'

The jackal felt it was quite hopeless to get what he wanted, and asked, 'Tell me, mother dove, how have you suddenly become so wise ?'

'It was the heron who told me,' replied she.

'And which way did he go?' said the jackal.

'Down there among the reeds. You can see him if you look,' said the dove.

Then the jackal nodded good-bye, and went quickly after the heron. He soon came up to the great bird, who was standing on a stone on the edge of the river watching for a nice fat fish. 'Tell me, heron,' said he, 'when the wind blows from that quarter, to which side do you turn?'

'And which side do you turn to?' asked the heron.

The jackal answered, 'I always turn to this side.'

'Then that is the side I turn to,' remarked the heron.

'And when the rain comes from that quarter, which side do you turn to?'

And the heron replied, 'And which side do you turn to?'

'Oh, I always turn to this side,' said the jackal.

'Then that is the side I turn to,' said the heron.

'And when the rain comes straight down, what do you do?'

'What do you do yourself?' asked the heron.

'I do this,' answered the jackal. 'I cover my head with my paws.'

'Then that is what I do,' said the heron. 'I cover my head with my wings,' and as he spoke he lifted his large wings and spread them completely over his head.

With one bound the jackal had seized him by the neck, and began to shake him.

'Oh, have pity, have pity!' cried the heron. 'I never did you any harm.'

'You told the dove how to get the better of me, and I am going to eat you for it.'

'But if you will let me go,' entreated the heron, 'I will show you the place where the panther has her lair.'

'Then you had better be quick about it,' said the jackal, holding tight on to the heron until he had pointed out the panther's den. 'Now you may go, my friend, for there is plenty of food here for me.'

So the jackal came up to the panther, and asked politely, 'Panther, would you like me to look after your children while you are out hunting?'

'I should be very much obliged,' said the panther; 'but be sure you take care of them. They always cry all the time that I am away.'

So saying she trotted off, and the jackal marched into the cave, where he found ten little panthers, and instantly ate one up. By-and-bye the panther returned from hunting, and said to him, 'Jackal, bring out my little ones for their supper.'

The jackal fetched them out one by one till he had brought out nine, and he took the last one and brought it out again, so the whole ten seemed to be there, and the panther was quite satisfied.

Next day she went again to the chase, and the jackal ate up another little panther, so now there were only eight. In the evening, when she came back, the panther said, 'Jackal, bring out my little ones!'

And the jackal brought out first one and then another, and the last one he brought out three times, so that the whole ten seemed to be there.

The following day the same thing happened, and the next and the next and the next, till at length there was not even one left, and the rest of the day the jackal busied himself with digging a large hole at the back of the den.

That night, when the panther returned from hunting, she said to him as usual, 'Jackal, bring out my little ones.'

But the jackal replied: 'Bring out your little ones, indeed! Why, you know as well as I do that you have eaten them all up.'

Of course the panther had not the least idea what the jackal meant by this, and only repeated, 'Jackal, bring out my children.' As she got no answer she entered the cave, but found no jackal, for he had crawled through the hole he had made and escaped. And, what was worse, she did not find the little ones either.

Now the panther was not going to let the jackal get off like that, and set off at a trot to catch him. The jackal, however, had got a good start, and he reached a place where a swarm of bees deposited their honey in the cleft of a rock. Then he stood still and waited till the panther came up to him: 'Jackal, where are my little ones?' she asked.

And the jackal answered: 'They are up there. It is where I keep school.'

The panther looked about, and then inquired, 'But where? I see nothing of them.'

'Come a little this way,' said the jackal, 'and you will hear how beautifully they sing.'

So the panther drew near the cleft of the rock.

'Don't you hear them?' said the jackal; 'they are in there,' and slipped away while the panther was listening to the song of the children.

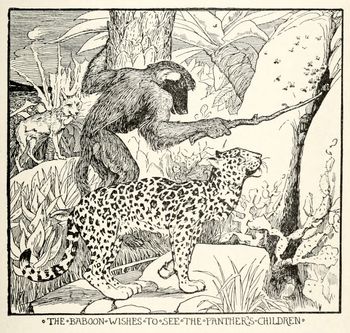

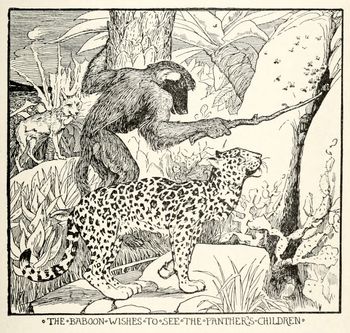

She was still standing in the same place when a baboon went by. 'What are you doing there, panther?'

'I am listening to my children singing. It is here that the jackal keeps his school.'

Then the baboon seized a stick, and poked it in the cleft of the rock, exclaiming, 'Well, then, I should like to see your children!'

The bees flew out in a huge swarm, and made furiously for the panther, whom they attacked on all sides, while the baboon soon climbed up out of the way, crying, as he perched himself on the branch of a tree, 'I wish you joy of your children!' while from afar the jackal's voice was heard exclaiming: 'Sting, her well! don't let her go!'

The panther galloped away as if she was mad, and flung herself into the nearest lake, but every time she raised her head, the bees stung her afresh so at last the poor beast was drowned altogether.

Contes populaires des Bassoutos. Recueillis et traduits par E. Jacottet. Paris: Leroux, Editeur.

Lo sciacallo, la colomba e la pantera

C'era una volta una colomba che costruì un bel nido morbido come casa per i suoi tre piccoli. Era molto orgogliosa della loro bellezza, e forse ne parlava ai suoi vicini più di quanto avrebbe dovuto fare, finché alla fine tutti, per miglia e miglia, sapevano dove si potessero trovare le tre più graziose piccole colombe dell’intero paese.

Un giorno uno sciacallo che si aggirava in cerca di cena giunse per caso ai piedi della roccia dove era nascosto il nido della colomba, e all'improvviso pensò che se non avesse potuto ottenere niente di meglio avrebbe potuto fare un boccone di una delle giovani colombe. Così gridò più forte che poteva, "Ohe, ohe, madre colomba."

E la colomba rispose, tremando di paura: "Che cosa volete, signore?"

"Uno dei vostri figli", disse lui; "e se non me lo farete, mangerò anche voi e gli altri."

La colomba fu quasi sconvolta dalle parole dello sciacallo, ma, per salvare le vite degli altri due, alla fine lanciò il piccolo fuori dal nido. Lo sciacallo lo mangiò e tornò a casa a dormire.

Nel frattempo la madre si era seduta sul bordo del suo nido, piangendo amaramente, quando un airone, che stava volando lentamente oltre la roccia, era preso da compassione per lei e si fermò a chiedere: "Che succede, povera colomba?"

E la colomba rispose: "Uno sciacallo è venuto e mi ha chiesto di dargli uno dei miei piccoli e ha detto che se avessi rifiutato, sarebbe saltato sul mio nido e ci avrebbe mangiati tutti".

Ma l'airone rispose: "Non avreste dovuto credergli. Non avrebbe mai potuto saltare così in alto. Vi ha solo ingannato perché voleva qualcosa per cena." E con queste parole l'airone volò via.

Era appena scomparso quando di nuovo lo sciacallo si avvicinò lentamente ai piedi della roccia. Quando vide la colomba, gridò una seconda volta: "Ohe, ohe, madre colomba!Datemi uno dei vostri piccoli, o salterò sul vostro nido e vi mangerò tutto.

Questa volta la colomba ne sapeva di più e rispose audacemente: "In verità non farò nulla del genere", sebbene le battesse forte il cuore per la paura quando vide lo sciacallo prepararsi a saltare.

Tuttavia, riuscì solo a ferirsi contro la roccia e pensò che sarebbe stato meglio limitarsi alle minacce, così ricominciò con il suo vecchio grido: "Madre colomba, madre colomba! Sbrigatevi a darmi uno dei vostri piccoli o vi mangerò tutti.”

Ma la madre si limitò a rispondere come prima: "In verità non farò nulla del genere, perché so che siamo al sicuro fuori dalla vostra portata".

Lo sciacallo capì che fosse quasi impossibile ottenere ciò che voleva e chiese: "Ditemi, madre colomba, come siete diventata improvvisamente così saggia?"

"È stato l'airone a dirmelo.", rispose.

"E da che parte è andato?"chiese lo sciacallo.

"Laggiù tra le canne. Potete vederlo se guardate, "disse la colomba.

Allora lo sciacallo le accennò un saluto e andò subito dietro l'airone. Ben presto si avvicinò al grande uccello, che stava in piedi su una pietra sul bordo del fiume a guardare un bel pesce grasso. "Dimmi, airone," disse lui, "quando il vento soffia da quel punto, verso quale lato ti volti?"

"E tu verso quale lato ti volti?" chiese l'airone.

Lo sciacallo rispose: "Mi volto sempre da questo lato".

"Allora quello è il lato verso il quale mi volto." disse l'airone.

"E quando piove da quel quartiere, a quale lato ti rivolgi?"

E l'airone rispose: "A quale lato ti rivolgi?"

"Oh, mi rivolgo sempre a questo lato", disse lo sciacallo.

"Allora quello è il lato a cui mi rivolgo," disse l'airone.

"E quando piove forte, che cosa fai?"

"Che cosa fai tu?" chiese l'airone.

Lo sciacallo rispose: “'Mi copro la testa con le zampe.”

"Ed è quello che faccio io", disse l'airone. "Mi copro la testa con le ali" e mentre parlava, sollevò le grandi ali e le spiegò completamente sopra la testa.

Con un sol colpo lo sciacallo l’afferrò per il collo e cominciò a scuoterlo.

"Oh, abbi pietà, abbi pietà!" gridò l'airone. "Non ti ho mai fatto del male."

"Hai detto alla colomba come farmela e ti mangerò per questo."

“Ma se mi lascerai andare”, implorò l'airone, “ti mostrerò il posto in cui la pantera ha il suo covo”.

“Allora è meglio che ti sbrighi” disse lo sciacallo, tenendosi stretto all'airone finché non gli mostrò la tana della pantera. "Ora puoi andare, amico mio, perché qui c'è molto da mangiare per me."

Così lo sciacallo si avvicinò alla pantera e chiese educatamente: "Pantera, vorresti che io badassi ai tuoi figli mentre sei fuori a caccia?"

"Ti sarei molto obbligato," disse la pantera; "ma assicurati di prenderti cura di loro. Piangono sempre per tutto il tempo in cui sono lontana. "

Così dicendo si allontanò e lo sciacallo entrò di buon passo nella caverna, in cui trovò dieci piccole pantere e ne mangiò subito una. Di lì a poco la pantera tornò dalla caccia e gli disse: "Sciacallo, fai i miei piccoli per la cena".

Lo sciacallo li recuperò uno alla volta finché ne ebbe portati fuori nove, prese l'ultimo e lo tirò fuori di nuovo, così che sembrassero essere lì tutti i dieci e la pantera fu abbastanza soddisfatta.

Il giorno seguente tornò di nuovo all'inseguimento e lo sciacallo mangiò un'altra piccola pantera, così ora ce n'erano solo otto. La sera, quando tornò, la pantera disse: "Sciacallo, fai uscire i miei piccoli!"

E lo sciacallo tirò fuori prima l'uno e poi l'altro e l'ultimo lo fece uscire tre volte, così che sembrò fossero lì tutti e dieci.

Il giorno dopo accadde la stessa cosa, la seguente, la successiva e l'altra, finché alla fine non ne rimase neppure uno, e il resto della giornata lo sciacallo si dedicò a scavare un grosso buco nella parte posteriore della tana.

Quella notte, quando la pantera tornò dalla caccia, gli disse come al solito: "Sciacallo, fai uscire i miei piccoli".

Ma lo sciacallo rispose: "Far uscire i tuoi piccoli, ma davvero!Lo sai bene quanto me che li hai mangiati tutti. "

Ovviamente la pantera non aveva la minima idea di cosa intendesse lo sciacallo e ripeté solo: "Sciacallo, fai uscire i miei cuccioli". Non avendo ottenuto risposta, entrò nella caverna, ma non trovò sciacallo, perché era strisciato attraverso il buco che aveva fatto ed era scappato. E, quel che è peggio, non trovò neanche i piccoli.

Ora la pantera non aveva intenzione di permettere che lo sciacallo se ne andasse in quel modo, e partì a passo veloce per catturarlo. Lo sciacallo, tuttavia, aveva un buon vantaggio e raggiunse un luogo in cui uno sciame di api depositava il miele nella fenditura di una roccia. Si fermò e attese che la pantera gli si avvicinasse: "Sciacallo, dove sono i miei piccoli?"chiese essa.

E lo sciacallo rispose: "Sono lassù. È lì che faccio lezione. "

La pantera si guardò intorno e poi domandò: "Ma dove? Non li vedo per niente.”

"Vieni un po' da questa parte", disse lo sciacallo, "e sentirai come cantano bene."

Così la pantera si avvicinò alla fenditura della roccia.

"Non li senti?" disse lo sciacallo; “Sono lì dentro” e sgusciò via mentre la pantera ascoltava la canzone dei bambini.

Era ancora nello stesso posto quando passò un babbuino. "Che cosa ci fai lì, pantera?"

'Sto ascoltando i miei bambini cantare. È qui che lo Sciacallo tiene lezione."

Poi il babbuino afferrò un bastone e lo infilò nella fessura della roccia, esclamando: "Bene, allora, mi piacerebbe vedere i tuoi figli!"

Le api volarono fuori in un enorme sciame e si gettarono furiosamente sulla pantera, che attaccarono da tutte le parti, mentre il babbo si arrampicò presto fuori dalla loro portata, strillando mentre si appollaiava sul ramo di un albero, "Ti auguro di goderti i tuoi piccoli!” mentre da lontano si udiva la voce dello sciacallo che esclamava: "Pungetela bene! Non lasciarla andare!”

La pantera galoppò via come se fosse impazzita e si gettò nel lago più vicino, ma ogni volta in cui alzava la testa, le api la pungevano di nuovo così che alla fine la povera bestia affogò.

Racconti popolari dei Basotho raccolti e tradotti da E. Jacottet, Parigi, e pubblicati da Leroux.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)