The Enchanted Snake

(MP3-15'14'')

There was once upon a time a poor woman who would have given all she possessed for a child, but she hadn't one.

Now it happened one day that her husband went to the wood to collect brushwood, and when he had brought it home, he discovered a pretty little snake among the twigs.

When Sabatella, for that was the name of the peasant's wife, saw the little beast, she sighed deeply and said, 'Even the snakes have their brood; I alone am unfortunate and have no children.' No sooner had she said these words than, to her intense surprise, the little snake looked up into her face and spoke: 'Since you have no children, be a mother to me instead, and I promise you will never repent it, for I will love you as if I were your own son.'

At first Sabatella was frightened to death at hearing a snake speak, but plucking up her courage, she replied, 'If it weren't for any other reason than your kindly thought, I would agree to what you say, and I will love you and look after you like a mother.'

So she gave the snake a little hole in the house for its bed, fed it with all the nicest food she could think of, and seemed as if she never could show it enough kindness. Day by day it grew bigger and fatter, and at last one morning it said to Cola-Mattheo, the peasant, whom it always regarded as its father, 'Dear papa, I am now of a suitable age and wish to marry.'

'I'm quite agreeable,' answered Mattheo, 'and I'll do my best to find another snake like yourself and arrange a match between you.'

'Why, if you do that,' replied the snake, 'we shall be no better than the vipers and reptiles, and that's not what I want at all. No; I'd much prefer to marry the King's daughter; therefore I pray you go without further delay, and demand an audience of the King, and tell him a snake wishes to marry his daughter.'

Cola-Mattheo, who was rather a simpleton, went as he was desired to the King, and having obtained an audience, he said, 'Your Majesty, I have often heard that people lose nothing by asking, so I have come to inform you that a snake wants to marry your daughter, and I'd be glad to know if you are willing to mate a dove with a serpent?'

The King, who saw at once that the man was a fool, said, in order to get quit of him, 'Go home and tell your friend the snake that if he can turn this palace into ivory, inlaid with gold and silver, before to-morrow at noon, I will let him marry my daughter.' And with a hearty laugh he dismissed the peasant.

When Cola-Mattheo brought this answer back to the snake, the little creature didn't seem the least put out, but said, 'To-morrow morning, before sunrise, you must go to the wood and gather a bunch of green herbs, and then rub the threshold of the palace with them, and you'll see what will happen.'

Cola-Mattheo, who was, as I have said before, a great simpleton, made no reply; but before sunrise next morning he went to the wood and gathered a bunch of St. John's Wort, and rosemary, and suchlike herbs, and rubbed them, as he had been told, on the floor of the palace. Hardly had he done so than the walls immediately turned into ivory, so richly inlaid with gold and silver that they dazzled the eyes of all beholders. The King, when he rose and saw the miracle that had been performed, was beside himself with amazement, and didn't know what in the world he was to do.

But when Cola-Mattheo came next day, and, in the name of the snake, demanded the hand of the Princess, the King replied, 'Don't be in such a hurry; if the snake really wants to marry my daughter, he must do some more things first, and one of these is to turn all the paths and walls of my garden into pure gold before noon to-morrow.'

When the snake was told of this new condition, he replied, 'To-morrow morning, early, you must go and collect all the odds and ends of rubbish you can find in the streets, and then take them and throw them on the paths and walls of the garden, and you'll see then if we won't be more than a match for the old King.'

So Cola-Mattheo rose at cock-crow, took a large basket under his arm, and carefully collected all the broken fragments of pots and pans, and jugs and lamps, and other trash of that sort. No sooner had he scattered them over the paths and walls of the King's garden than they became one blaze of glittering gold, so that everyone's eyes were dazzled with the brilliancy, and everyone's soul was filled with wonder. The King, too, was amazed at the sight, but still he couldn't make up his mind to part with his daughter, so when Cola-Mattheo came to remind him of his promise he replied, 'I have still a third demand to make. If the snake can turn all the trees and fruit of my garden into precious stones, then I promise him my daughter in marriage.'

When the peasant informed the snake what the King had said, he replied, 'To-morrow morning, early, you must go to the market and buy all the fruit you see there, and then sow all the stones and seeds in the palace garden, and, if I'm not mistaken, the King will be satisfied with the result.'

Cola-Mattheo rose at dawn, and taking a basket on his arm, he went to the market, and bought all the pomegranates, apricots, cherries, and other fruit he could find there, and sowed the seeds and stones in the palace garden. In one moment, the trees were all ablaze with rubies, emeralds, diamonds, and every other precious stone you can think of.

This time the King felt obliged to keep his promise, and calling his daughter to him, he said, 'My dear Grannonia,' for that was the Princess's name, 'more as a joke than anything else, I demanded what seemed to me impossibilities from your bridegroom, but now that he has done all I required, I am bound to stick to my part of the bargain. Be a good child, and as you love me, do not force me to break my word, but give yourself up with as good grace as you can to a most unhappy fate.'

'Do with me what you like, my lord and father, for your will is my law,' answered Grannonia.

When the King heard this, he told Cola-Mattheo to bring the snake to the palace, and said that he was prepared to receive the creature as his son-in-law.

The snake arrived at court in a carriage made of gold and drawn by six white elephants; but wherever it appeared on the way, the people fled in terror at the sight of the fearful reptile.

When the snake reached the palace, all the courtiers shook and trembled with fear down to the very scullion, and the King and Queen were in such a state of nervous collapse that they hid themselves in a far-away turret. Grannonia alone kept her presence of mind, and although both her father and mother implored her to fly for her life, she wouldn't move a step, saying, 'I'm certainly not going to fly from the man you have chosen for my husband.'

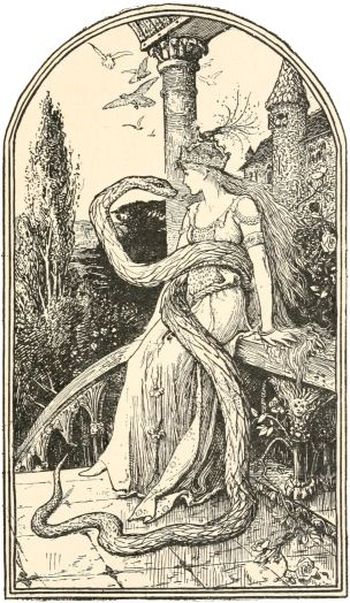

As soon as the snake saw Grannonia, it wound its tail round her and kissed her.

Then, leading her into a room, it shut the door, and throwing off its skin, it changed into a beautiful young man with golden locks, and flashing eyes, who embraced Grannonia tenderly, and said all sorts of pretty things to her.

When the King saw the snake shut itself into a room with his daughter, he said to his wife, 'Heaven be merciful to our child, for I fear it is all over with her now. This cursed snake has most likely swallowed her up.' Then they put their eyes to the keyhole to see what had happened.

Their amazement knew no bounds when they saw a beautiful youth standing before their daughter with the snake's skin lying on the floor beside him. In their excitement they burst open the door, and seizing the skin they threw it into the fire. But no sooner had they done this than the young man called out, 'Oh, wretched people! what have you done?' and before they had time to look round he had changed himself into a dove, and dashing against the window he broke a pane of glass, and flew away from their sight.

But Grannonia, who in one and the same moment saw herself merry and sad, cheerful and despairing, rich and beggared, complained bitterly over this robbery of her happiness, this poisoning of her cup of joy, this unlucky stroke of fortune, and laid all the blame on her parents, though they assured her that they had meant no harm. But the Princess refused to be comforted, and at night, when all the inhabitants of the palace were asleep, she stole out by a back door, disguised as a peasant woman, determined to seek for her lost happiness till she found it. When she got to the outskirts of the town, led by the light of the moon, she met a fox, who offered to accompany her, an offer which Grannonia gladly accepted, saying 'You are most heartily welcome, for I don't know my way at all about the neighbourhood.'

So they went on their way together, and came at last to a wood, where, being tired with walking, they paused to rest under the shade of a tree, where a spring of water sported with the tender grass, refreshing it with its crystal spray.

They laid themselves down on the green carpet and soon fell fast asleep, and did not waken again till the sun was high in the heavens. They rose up and stood for some time listening to the birds singing, because Grannonia delighted in their songs.

When the fox perceived this, he said: 'If you only understood, as I do, what these little birds are saying, your pleasure would be even greater.'

Provoked by his words—for we all know that curiosity is as deeply inborn in every woman as even the love of talking—Grannonia implored the fox to tell her what the birds had said.

At first the wily fox refused to tell her what he had gathered from the conversation of the birds, but at last he gave way to her entreaties, and told her that they had spoken of the misfortunes of a beautiful young Prince, whom a wicked enchantress had turned into a snake for the period of seven years. At the end of this time he had fallen in love with a charming Princess, but that when he had shut himself up into a room with her, and had thrown off his snake's skin, her parents had forced their way into the room and had burnt the skin, whereupon the Prince, changed into the likeness of a dove, had broken a pane of glass in trying to fly out of the window, and had wounded himself so badly that the doctors despaired of his life.

Grannonia, when she learnt that they were talking of her lover, asked at once whose son he was, and if there was any hope of his recovery; to which the fox made answer that the birds had said he was the son of the King of Vallone Grosso, and that the only thing that could cure him was to rub the wounds on his head with the blood of the very birds who had told the tale.

Then Grannonia knelt down before the fox, and begged him in her sweetest way to catch the birds for her and procure their blood, promising at the same time to reward him richly.

'All right,' said the fox, 'only don't be in such a hurry; let's wait till night, when the little birds have gone to roost, then I'll climb up and catch them all for you.'

So they passed the day, talking now of the beauty of the Prince, now of the father of the Princess, and then of the misfortune that had happened. At last the night arrived, and all the little birds were asleep high up on the branches of a big tree. The fox climbed up stealthily and caught the little creatures with his paws one after the other; and when he had killed them all he put their blood into a little bottle which he wore at his side and returned with it to Grannonia, who was beside herself with joy at the result of the fox's raid. But the fox said, 'My dear daughter, your joy is in vain, because, let me tell you, this blood is of no earthly use to you unless you add some of mine to it,' and with these words he took to his heels.

Grannonia, who saw her hopes dashed to the ground in this cruel way, had recourse to flattery and cunning, weapons which have often stood the sex in good stead, and called out after the fox, 'Father Fox, you would be quite right to save your skin, if, in the first place, I didn't feel I owed so much to you, and if, in the second, there weren't other foxes in the world; but as you know how grateful I feel to you, and as there are heaps of other foxes about, you can trust yourself to me. Don't behave like the cow that kicks the pail over after it has filled it with milk, but continue your journey with me, and when we get to the capital you can sell me to the King as a servant girl.'

It never entered the fox's head that even foxes can be outwitted, so after a bit he consented to go with her; but he hadn't gone far before the cunning girl seized a stick, and gave him such a blow with it on the head, that he dropped down dead on the spot. Then Grannonia took some of his blood and poured it into her little bottle; and went on her way as fast as she could to Vallone Grosso.

When she arrived there she went straight to the Royal palace, and let the King be told she had come to cure the young Prince.

The King commanded her to be brought before him at once, and was much astonished when he saw that it was a girl who undertook to do what all the cleverest doctors of his kingdom had failed in. As an attempt hurts no one, he willingly consented that she should do what she could.

'All I ask,' said Grannonia, 'is that, should I succeed in what you desire, you will give me your son in marriage.'

The King, who had given up all hopes of his son's recovery, replied: 'Only restore him to life and health and he shall be yours. It is only fair to give her a husband who gives me a son.'

And so they went into the Prince's room. The moment Grannonia had rubbed the blood on his wounds the illness left him, and he was as sound and well as ever. When the King saw his son thus marvellously restored to life and health, he turned to him and said: 'My dear son, I thought of you as dead, and now, to my great joy and amazement, you are alive again. I promised this young woman that if she should cure you, to bestow your hand and heart on her, and seeing that Heaven has been gracious, you must fulfil the promise I made her; for gratitude alone forces me to pay this debt.'

But the Prince answered: 'My lord and father, I would that my will were as free as my love for you is great. But as I have plighted my word to another maiden, you will see yourself, and so will this young woman, that I cannot go back from my word, and be faithless to her whom I love.'

When Grannonia heard these words, and saw how deeply rooted the Prince's love for her was, she felt very happy, and blushing rosy red, she said: 'But should I get the other lady to give up her rights, would you then consent to marry me?'

'Far be it from me,' replied the Prince, 'to banish the beautiful picture of my love from my heart. Whatever she may say, my heart and desire will remain the same, and though I were to lose my life for it, I couldn't consent to this exchange.'

Grannonia could keep silence no longer, and throwing off her peasant's disguise, she discovered herself to the Prince, who was nearly beside himself with joy when he recognised his fair lady-love. He then told his father at once who she was, and what she had done and suffered for his sake.

Then they invited the King and Queen of Starza-Longa to their Court, and had a great wedding feast, and proved once more that there is no better seasoning for the joys of true love than a few pangs of grief.

Unknown.

Il serpente incantato

C’era una volta una povera donna che avrebbe dato tutto ciò che possedeva per un bambino, ma non ne aveva nessuno.

Un giorno accadde che il marito andasse nel bosco a raccogliere rami e quando fu tornato a casa, scoprì un grazioso serpentello tra i ramoscelli.

Quando Sabatella, perché così si chiamava la moglie del contadino, vide la bestiola, sospiro profondamente e disse: “Persino i serpenti hanno una covata; solo io sono così sfortunata da non avere bambini.” Non appena ebbe pronunciato queste parole, con sua grande sorpresa il serpentello la guardò in faccia e parlò: “Poiché non hai bambini, fai piuttosto da madre a me e ti prometto che non te ne pentirai mai perché ti amerò come fossi tuo figlio.”

Dapprima Sabatella fu spaventata a morte nel sentir parlare un serpente, ma, fattasi coraggio, rispose: “Non fosse per nessun’altra ragione che il tuo gentile pensiero, farò volentieri ciò che dici e ti amerò e ti accudirò come una madre.”

Così fece una piccola tana in casa come letto per il serpentello, lo nutrì con i cibi più deliziosi ai quali pensò e sembrava che non potesse mai mostrargli abbastanza gentilezza. Giorno dopo giorno il serpentello divenne più grande e più grosso e infine una mattina disse a Cola Matteo, il contadino, che aveva sempre considerato suo padre: “Caro papà, ora sono nell’età giusta e desidero sposarmi.”

Matteo rispose: “Sono completamente d’accordo e farò del mio meglio per trovare un altro serpente come te e combinare le nozze tra di voi.”

Il serpente rispose: “Ebbene, se lo fai, non saranno né vipere né rettili, io non li voglio affatto. No, preferirei di più sposare la figlia del Re; perciò ti prego di andare senza ulteriore indugio, di chiedere udienza al Re e di dirgli che un serpente desidera sposare sua figlia.”

Cola Matteo, che era alquanto sempliciotto, andò dal Re come lui desiderava e, ottenuta udienza, disse: “Vostra Maestà, ho spesso sentito die che la gente non ottiene nulla se non chiede, così sono venuto a informarvi che un serpente vuole sposare vostra figlia e che gradirei sapere se voi siete disposto a unire una colomba con un serpente.”

Il Re, il quale aveva capito subito che l’uomo era uno sciocco, per farlo stare tranquillo, disse: “Andate a casa e dite al vostro amico serpente che se potrà tramutare questo palazzo in avorio, intarsiato d’oro e d’argento, prima di domani a mezzogiorno, io gli lascerò sposare mia figlia.” E con una risata di cuore, congedò il contadino.

Quando Cola Matteo riferì questa risposta al serpente, la creaturina non sembrò minimamente darsi pena, ma disse: “Domattina, prima dell’alba, devi andare nel bosco a raccogliere una manciata di erbe verdi e poi strofinare con esse la soglia del palazzo e vedrai che cosa accadrà.”

Come abbiamo detto prima, Cola Matteo era un gran sempliciotto e non rispose; il mattino seguente prima dell’alba andò nel bosco e raccolse una manciata di iperico, di rosmarino e di erbe simili e, come gli era stato detto, le strofinò sul pavimento del palazzo. Lo aveva appena fatto che i muri immediatamente si tramutarono in avorio, così riccamente intarsiati d’oro e d’argento che abbagliarono gli occhi di tutti i presenti. Quando il Re si alzò e vide il miracolo compiuto, fu egli stesso stupefatto e non sapeva che diamine dovesse fare.

Quando Cola Matteo venne il giorno seguente e, in nome del serpente, chiese la mano della Principessa, il Re rispose: “Non avere tanta fretta; se il serpente vuole davvero sposare mia figlia, deve prima fare altre cose e una di esse è tramutare tutti i sentieri e i muri del mio giardino in oro puro prima di domani a mezzogiorno.”

Quando fu detta al serpente questa nuova condizione, rispose: “Domattina presto dovrai andare a raccogliere tutti i rifiuti che troverai nelle strade e poi gettarli sui sentieri e sui muri del giardino, e vedrai se non terremo testa al vecchio Re.”

Così Cola Matteo si alzò al canto del gallo, si mise sottobraccio un grosso cesto e raccolse attentamente tutti i cocci di vasi e di tegami, di brocche e di lampade e ogni altro gene re di spazzatura. Li aveva appena sui sentieri e sui muri del giardino del Re che divennero una vampa d’oro scintillante così che ognuno ebbe gli occhi abbagliati da tanta lucentezza e l’animo colmo di stupore. Anche il Re fu stupito a quella vista, ma non poteva decidersi a separarsi dalla figlia, così quando Cola Matteo venne a rammentargli la promessa, rispose: “Ho una terza richiesta da fare. Se il serpente può trasformare tutti gli alberi e i frutti del mio giardino in pietre preziose, gli prometto in sposa mia figlia.”

Quando il contadino informò il serpente di ciò che il Re aveva detto, rispose: “Domattina presto devi andare al mercato e comprare tutta la frutta che vedrai là e poi seminare tutti i noccioli e i semi nel giardino del palazzo e, se non mi sbaglio, il Re sarà soddisfatto del risultato.

Cola Matteo si alzò all’alba e, infilandosi al braccio un cestino, andò al mercato e acquistò tutte le melagrane, le albicocche, le ciliegie e gli altri frutti che poté trovare; seminò i semi e i noccioli nel giardino del palazzo. In un istante gli alberi furono tutti risplendenti di rubini, smeraldi, diamanti e ogni altra pietra preziosa che potete immaginare.

Stavolta il Re si sentì obbligato a mantenere la promessa e, chiamando la figlia, le disse: “Mia cara Grannonia” perché così si chiamava la Principessa, “più per gioco che per altro, ho chiesto al tuo pretendente ciò che mi sembrava impossibile, ma ora che lui ha esaudito tutte le mie richieste, sono costretto a stare ai patti. Sii una brava figliola e siccome mi ami, non costringermi a infrangere la promessa, ma accetta con la buona grazia di cui sei in grado il più infelice dei destini.”

”Mio signor e padre mio, fate di me ciò che volete perché il vostro desiderio per me è legge.” rispose Grannonia.

Quando il Re lo sentì, disse a Cola Matteo di portare a palazzo il serpente e di essere pronto ad accogliere la creatura come genero.

Il serpente giunse a corte in una carrozza d’oro trainata da sei elefanti; ma in qualsiasi luogo comparisse lungo il tragitto, la gente fuggiva terrorizzata alla vista dello spaventoso rettile.

Quando il serpente raggiunse il palazzo, tutti i cortigiani fino all’ultimo sguattero tremarono di paura e il Re e la Regina si trovavano in un tale stato di tracollo nervoso che si nascosero in una torretta lontana. Solo Grannonia mantenne il controllo di sé e sebbene sia il padre che la madre l’avessero implorata di salvarsi la vita, lei non volle muovere un passo, dicendo: “Di certo non fuggirò davanti all’uomo che mi avete scelto come marito.”

Appena il serpente vide Grannonia, le si avvolse attorno e la baciò.

Poi conducendola in una stanza, chiuse la porta e, liberandosi della pelle, si trasformò in un bellissimo giovane con I riccioli Biondi e gli occhi luminosi, che abbracciò teneramente Grannonia e le disse ogni sorta di parole gentili.

Quando il Re vide il serpente chiudersi in camera con la figlia, disse alla moglie: “Il cielo abbia pietà della nostra bambina, perché temo che per lei sia finita. È più probabile che questo maledetto serpente l’abbia divorata.” Poi appoggiarono l’occhio al buco della serratura per vedere che cosa fosse accaduto.

Il loro stupore fu senza limiti quando videro uno splendido giovane in piedi davanti a loro figlia, con la pelle del serpente che giaceva sul pavimento accanto a lui. Per l’eccitazione irruppero dalla porta e afferrata la pelle, la gettarono nel fuoco. Lo avevano appena fatto che il giovane gridò: ”Sventurati! Che cosa avete fatto?” e prima che avessero il tempo di guardarsi attorno, si trasformò in una colomba e, lanciandosi contro la finestra, ruppe una lastra di vetro e volò via dalla loro vista.

Ma Grannonia, che in un solo momento si sentì allegra e triste, speranzosa e disperata, ricca e povera, si rammaricò amaramente per la perdita della felicità, l’avvelenamento della coppa della sua gioia, lo sfortunato colpo del destino e diede tutta la colpa ai genitori, sebbene essi le assicurassero che non intendevano fare alcun male. La Principessa rifiutò ogni conforto e la notte, quando tutti gli abitanti del palazzo erano addormentati, fuggì da una porta secondaria, travestita da contadina, decisa a cercare la fortuna perduta fino a ritrovarla. Quando fu alla periferia della città, illuminata dalla luce della luna, incontrò una volpe che si offrì di accompagnarla, offerta che Grannonia accettò volentieri, dicendo: “Ti do il benvenuto di cuore perché non so dove andare nei dintorni.”

Così proseguirono insieme e infine giunsero in un bosco in cui, essendo stanchi per la camminata, si fermarono a riposare all’ombra di un albero, presso il quale un ruscello giocava con la tenera erba, rinfrescandola con spruzzi cristallini.

Giacquero sul manto verde e ben presto si addormentarono; non si svegliarono finché il sole fu alto nel cielo. Si alzarono e restarono per un po’ di tempo ad ascoltare gli uccelli che cantavano perché Grannonia era deliziata dalle loro canzoni.

Quando la volpe se ne accorse, disse: “Se solo tu comprendessi, come me, ciò che stanno dicendo gli uccelli, il tuo piacere sarebbe ancora maggiore.”

Stimolata da queste parole – perché sappiamo che la curiosità è profondamente connaturata in ogni donna, così come la passione per le chiacchiere – Grannonia implorò la volpe di dirle ciò che avessero detto gli uccelli.

Dapprima la scaltra volpe rifiutò di dirle ciò che aveva appreso dalla conversazione degli uccelli, ma alla fine accolse la sua preghiera e le raccontò che avevano parlato delle disgrazie di un bellissimo Principe, che un malvagio incantesimo aveva trasformato in un serpente per sette anni. Alla fine di quel periodo si era innamorato di un’affascinante Principessa, ma quando si era chiuso in una stanza con lei e liberato della pelle di serpente, i suoi genitori si erano introdotti a forza nella stanza e avevano bruciato la pelle, dopo di che il Principe, tramutato in sembianza di colomba, aveva rotto una lastra di vetro nel tentativo di volare fuori dalla finestra e si era ferito così gravemente che i dottori temevano per la sua vita.

Quando Grannonia comprese che stavano parlando del suo innamorato, chiese subito di chi fosse figlio e se ci fosse alcuna speranza di ritrovarlo; al che la volpe rispose che gli uccelli aveva detto fosse il figlio del Re di Vallone Grosso, e che l’unica cosa che potesse curarlo fosse lo strofinargli le ferite sul capo proprio con il sangue degli uccelli che avevano narrato la storia.

Allora Grannonia cadde in ginocchio davanti alla volpe e lo pregò nel modo più dolce di catturare gli uccelli per lei e di procurarle il loro sangue, promettendogli nel medesimo tempo di ricompensarlo generosamente.

La volpe rispose: “D’accordo, solo non devi avere fretta, lascia che cali la notte, quando gli uccellini si preparano a dormire, allora mi arrampicherò e li catturerò tutti per te.”

Così trascorsero il giorno chiacchierando ora della bellezza del principe, ora del padre della Principessa e poi della disgrazia che era capitate. Infine scese la notte e gli uccellini si erano addormentati in alto tra i rami di un grosso albero. La volpe si arrampicò furtivamente e catturò una dopo l’altra le creaturine con le zampe; quando le ebbe uccise tutte, mise il loro sangue in una bottiglietta che si mise al fianco e con essa tornò da Grannonia, felice per il risultato della caccia della volpe. Ma la volpe disse: “Mia cara figlia, inutile è la tua gioia, perché, lascia che te lo dica, questo sangue non serve assolutamente a niente a meno che tu non gli aggiunga un po’ del mio.” E con queste parole girò i tacchi.

Grannonia, che vedeva le proprie speranze crollare in un questo crudele modo, ricorse all’adulazione all’astuzia, armi che spesso tornano utili al sesso femminile, e chiamò la volpe: “Padre volpe, sarebbe giusto che ti salvassi la vita se, in primo luogo, io non sapessi di doverti molto e se, in secondo luogo, non ci fossero altre volpi al mondo; tu sai quanto ti sia grata e siccome c’è gran quantità di altre volpi, puoi fidarti di me. Non comportarti come la mucca che calcia via il secchio che è stato riempito di latte, ma continua il viaggio con me e, quando saremo giunti nella capitale, potrai offrirmi al Re come sguattera.”

Alla volpe non passò nemmeno per l’anticamera del cervello che le volpi potessero mai essere superate in astuzia, così dopo un po’ acconsentì ad andare con lei; ma non erano ancora andati molto lontano che l’astuta ragazza afferrò un bastone e gli diede una tale botta in testa, che la volpe cadde a terra morta. Allora Grannonia prese un po’ del suo sangue e lo versò nella bottiglietta; poi riprese la strada verso Vallone Grosso più in fretta che poté.

Quando arrivò, andò dritta al palazzo reale e fece dire al Re di essere venuta per curare il giovane Principe.

Il Re ordinò che fosse condotta subito al suo cospetto e rimase sbalordito quando vide che si trattava di una ragazza che si assumeva l’impegno di fare ciò in cui tutti i più abili dottori del suo regno avevano fallito. Siccome un tentativo non avrebbe fatto male a nessuno, acconsentì volentieri che lei facesse ciò che poteva.

Grannonia disse: “Tutto ciò che chiedo è che mi facciate sposare vostro figlio, se avrò successo in ciò che desiderate.”

Il Re, il quale che riponeva tutte le speranze nella guarigione del figlio, disse: “Restituiscili la vita e la salute e sarà tuo. È giusto dare un marito a colei che mi restituisce un figlio.”

Così andarono nella stanza del Principe. Nel momento in cui Grannonia strofinò il sangue sulle sue ferite, la malattia lo abbandonò e lui fu sano e salvo come sempre. Quando il Re vide suo figlio così meravigliosamente restituito alla vita e alla salute, gli si rivolse e disse: “Figlio caro, ti davo per morto e adesso, con mia grande gioia e sorpresa, sei di nuovo vivo. Ho promesso a questa giovane donna, se ti avesse curato, di concederle la tua mano e il tuo cuore e, vedendo che il Cielo è stato così benevolo, devi mantenere la promessa che le ho fatto perché solo la gratitudine mi obbliga a pagare questo debito.”

Il Principe rispose: “Mio signore e padre, vorrei che la mia volontà fosse tanto libera quanto è grande il mio amore per voi. Ma siccome io mi sono impegnato con un’altra fanciulla, potrete vedere voi stesso, e altrettanto farà questa giovane donna, che non posso infrangere la mia promessa e essere infedele a colei che amo.”

Quando Grannonia udì queste parole e vide quanto fosse profondamente radicato l’amore del Principe per lei, si sentì assai felice e, arrossendo, disse: “Ma se io ottenessi che l’altra dama rinunciasse ai propri diritti, allora acconsentiresti a sposarmi?”

Il Principe rispose: “Lungi da me il bandire dal mio cuore il bellissimo volto del mio amore. Qualsiasi cosa lei dicesse, il mio cuore e il mio desiderio rimarrebbero i medesimi e quantunque io dovessi perde per ciò la vita, non permetterei questo cambio.”

Grannonia non rimase più a lungo in silenzio e, gettando via il travestimento da contadina, si rivelò al Principe il quale quasi venne meno per la felicità nel riconoscere la sua amata. Allora disse subito a suo padre chi fosse e che cosa avesse fatto e sofferto nel suo interesse.

Poi invitarono a corte il Re e la Regina di Starza-Longa e ci fu una grande festa di nozze, a riprova ancora una volta del fatto che non esiste miglior condimento di qualche fitta di dolore per le gioie del vero amore.

Origine sconosciuta

Non viene citata l’origine, ma si tratta di una fiaba italiana, più precisamente un adattamento de La serpe, inclusa ne Il racconto dei racconti di Giambattista Basile, in cui costituisce il trattenimento quinto della giornata seconda (edizione Adelphi 1994, pagg. 211-221) (N.d.T.)

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)