A Tale Of The Tontlawald

Long, long ago there stood in the midst of a country covered with lakes a vast stretch of moorland called the Tontlawald, on which no man ever dared set foot. From time to time a few bold spirits had been drawn by curiosity to its borders, and on their return had reported that they had caught a glimpse of a ruined house in a grove of thick trees, and round about it were a crowd of beings resembling men, swarming over the grass like bees. The men were as dirty and ragged as gipsies, and there were besides a quantity of old women and half-naked children.

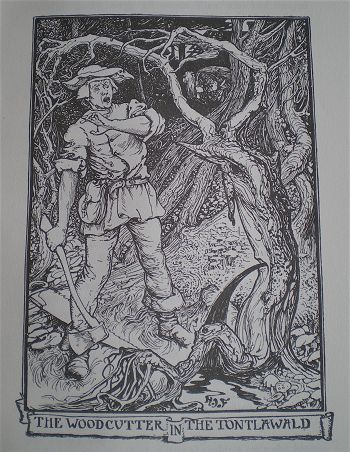

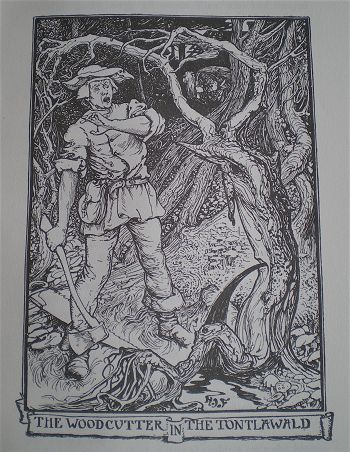

One night a peasant who was returning home from a feast wandered a little farther into the Tontlawald, and came back with the same story. A countless number of women and children were gathered round a huge fire, and some were seated on the ground, while others danced strange dances on the smooth grass. One old crone had a broad iron ladle in her hand, with which every now and then she stirred the fire, but the moment she touched the glowing ashes the children rushed away, shrieking like night owls, and it was a long while before they ventured to steal back. And besides all this there had once or twice been seen a little old man with a long beard creeping out of the forest, carrying a sack bigger than himself. The women and children ran by his side, weeping and trying to drag the sack from off his back, but he shook them off, and went on his way. There was also a tale of a magnificent black cat as large as a foal, but men could not believe all the wonders told by the peasant, and it was difficult to make out what was true and what was false in his story. However, the fact remained that strange things did happen there, and the King of Sweden, to whom this part of the country belonged, more than once gave orders to cut down the haunted wood, but there was no one with courage enough to obey his commands. At length one man, bolder than the rest, struck his axe into a tree, but his blow was followed by a stream of blood and shrieks as of a human creature in pain. The terrified woodcutter fled as fast as his legs would carry him, and after that neither orders nor threats would drive anybody to the enchanted moor.

A few miles from the Tontlawald was a large village, where dwelt a peasant who had recently married a young wife. As not uncommonly happens in such cases, she turned the whole house upside down, and the two quarrelled and fought all day long.

By his first wife the peasant had a daughter called Elsa, a good quiet girl, who only wanted to live in peace, but this her stepmother would not allow. She beat and cuffed the poor child from morning till night, but as the stepmother had the whip-hand of her husband there was no remedy.

For two years Elsa suffered all this ill-treatment, when one day she went out with the other village children to pluck strawberries. Carelessly they wandered on, till at last they reached the edge of the Tontlawald, where the finest strawberries grew, making the grass red with their colour. The children flung themselves down on the ground, and, after eating as many as they wanted, began to pile up their baskets, when suddenly a cry arose from one of the older boys:

'Run, run as fast as you can! We are in the Tontlawald!'

Quicker than lightning they sprang to their feet, and rushed madly away, all except Elsa, who had strayed farther than the rest, and had found a bed of the finest strawberries right under the trees. Like the others, she heard the boy's cry, but could not make up her mind to leave the strawberries.

'After all, what does it matter?' thought she. 'The dwellers in the Tontlawald cannot be worse than my stepmother'; and looking up she saw a little black dog with a silver bell on its neck come barking towards her, followed by a maiden clad all in silk.

'Be quiet,' said she; then turning to Elsa she added: 'I am so glad you did not run away with the other children. Stay here with me and be my friend, and we will play delightful games together, and every day we will go and gather strawberries. Nobody will dare to beat you if I tell them not. Come, let us go to my mother'; and taking Elsa's hand she led her deeper into the wood, the little black dog jumping up beside them and barking with pleasure.

Oh! what wonders and splendours unfolded themselves before Elsa's astonished eyes! She thought she really must be in Heaven. Fruit trees and bushes loaded with fruit stood before them, while birds gayer than the brightest butterfly sat in their branches and filled the air with their song. And the birds were not shy, but let the girls take them in their hands, and stroke their gold and silver feathers. In the centre of the garden was the dwelling-house, shining with glass and precious stones, and in the doorway sat a woman in rich garments, who turned to Elsa's companion and asked:

'What sort of a guest are you bringing to me?'

'I found her alone in the wood,' replied her daughter, 'and brought her back with me for a companion. You will let her stay?'

The mother laughed, but said nothing, only she looked Elsa up and down sharply. Then she told the girl to come near, and stroked her cheeks and spoke kindly to her, asking if her parents were alive, and if she really would like to stay with them. Elsa stooped and kissed her hand, then, kneeling down, buried her face in the woman's lap, and sobbed out:

'My mother has lain for many years under the ground. My father is still alive, but I am nothing to him, and my stepmother beats me all the day long. I can do nothing right, so let me, I pray you, stay with you. I will look after the flocks or do any work you tell me; I will obey your lightest word; only do not, I entreat you, send me back to her. She will half kill me for not having come back with the other children.'

And the woman smiled and answered, 'Well, we will see what we can do with you,' and, rising, went into the house.

Then the daughter said to Elsa, 'Fear nothing, my mother will be your friend. I saw by the way she looked that she would grant your request when she had thought over it,' and, telling Elsa to wait, she entered the house to seek her mother. Elsa meanwhile was tossed about between hope and fear, and felt as if the girl would never come.

At last Elsa saw her crossing the grass with a box in her hand.

'My mother says we may play together to-day, as she wants to make up her mind what to do about you. But I hope you will stay here always, as I can't bear you to go away. Have you ever been on the sea?'

'The sea?' asked Elsa, staring; 'what is that? I've never heard of such a thing!'

'Oh, I'll soon show you,' answered the girl, taking the lid from the box, and at the very bottom lay a scrap of a cloak, a mussel shell, and two fish scales. Two drops of water were glistening on the cloak, and these the girl shook on the ground. In an instant the garden and lawn and everything else had vanished utterly, as if the earth had opened and swallowed them up, and as far as the eye could reach you could see nothing but water, which seemed at last to touch heaven itself. Only under their feet was a tiny dry spot. Then the girl placed the mussel shell on the water and took the fish scales in her hand. The mussel shell grew bigger and bigger, and turned into a pretty little boat, which would have held a dozen children. The girls stepped in, Elsa very cautiously, for which she was much laughed at by her friend, who used the fish scales for a rudder. The waves rocked the girls softly, as if they were lying in a cradle, and they floated on till they met other boats filled with men, singing and making merry.

'We must sing you a song in return,' said the girl, but as Elsa did not know any songs, she had to sing by herself. Elsa could not understand any of the men's songs, but one word, she noticed, came over and over again, and that was 'Kisika.' Elsa asked what it meant, and the girl replied that it was her name.

It was all so pleasant that they might have stayed there for ever had not a voice cried out to them, 'Children, it is time for you to come home!'

So Kisika took the little box out of her pocket, with the piece of cloth lying in it, and dipped the cloth in the water, and lo! they were standing close to a splendid house in the middle of the garden. Everything round them was dry and firm, and there was no water anywhere. The mussel shell and the fish scales were put back in the box, and the girls went in.

They entered a large hall, where four and twenty richly dressed women were sitting round a table, looking as if they were about to attend a wedding. At the head of the table sat the lady of the house in a golden chair.

Elsa did not know which way to look, for everything that met her eyes was more beautiful than she could have dreamed possible. But she sat down with the rest, and ate some delicious fruit, and thought she must be in heaven. The guests talked softly, but their speech was strange to Elsa, and she understood nothing of what was said. Then the hostess turned round and whispered something to a maid behind her chair, and the maid left the hall, and when she came back she brought a little old man with her, who had a beard longer than himself. He bowed low to the lady and then stood quietly near the door.

'Do you see this girl?' said the lady of the house, pointing to Elsa. 'I wish to adopt her for my daughter. Make me a copy of her, which we can send to her native village instead of herself.'

The old man looked Elsa all up and down, as if he was taking her measure, bowed again to the lady, and left the hall. After dinner the lady said kindly to Elsa, 'Kisika has begged me to let you stay with her, and you have told her you would like to live here. Is that so?'

At these words Elsa fell on her knees, and kissed the lady's hands and feet in gratitude for her escape from her cruel stepmother; but her hostess raised her from the ground and patted her head, saying, 'All will go well as long as you are a good, obedient child, and I will take care of you and see that you want for nothing till you are grown up and can look after yourself. My waiting-maid, who teaches Kisika all sorts of fine handiwork, shall teach you too.'

Not long after the old man came back with a mould full of clay on his shoulders, and a little covered basket in his left hand. He put down his mould and his basket on the ground, took up a handful of clay, and made a doll as large as life. When it was finished he bored a hole in the doll's breast and put a bit of bread inside; then, drawing a snake out of the basket, forced it to enter the hollow body.

'Now,' he said to the lady, 'all we want is a drop of the maiden's blood.'

When she heard this Elsa grew white with horror, for she thought she was selling her soul to the evil one.

'Do not be afraid!' the lady hastened to say; 'we do not want your blood for any bad purpose, but rather to give you freedom and happiness.'

Then she took a tiny golden needle, pricked Elsa in the arm, and gave the needle to the old man, who stuck it into the heart of the doll. When this was done he placed the figure in the basket, promising that the next day they should all see what a beautiful piece of work he had finished.

When Elsa awoke the next morning in her silken bed, with its soft white pillows, she saw a beautiful dress lying over the back of a chair, ready for her to put on. A maid came in to comb out her long hair, and brought the finest linen for her use; but nothing gave Elsa so much joy as the little pair of embroidered shoes that she held in her hand, for the girl had hitherto been forced to run about barefoot by her cruel stepmother. In her excitement she never gave a thought to the rough clothes she had worn the day before, which had disappeared as if by magic during the night. Who could have taken them? Well, she was to know that by-and-by. But we can guess that the doll had been dressed in them, which was to go back to the village in her stead. By the time the sun rose the doll had attained her full size, and no one could have told one girl from the other. Elsa started back when she met herself as she looked only yesterday.

'You must not be frightened,' said the lady, when she noticed her terror; 'this clay figure can do you no harm. It is for your stepmother, that she may beat it instead of you. Let her flog it as hard as she will, it can never feel any pain. And if the wicked woman does not come one day to a better mind your double will be able at last to give her the punishment she deserves.'

From this moment Elsa's life was that of the ordinary happy child, who has been rocked to sleep in her babyhood in a lovely golden cradle. She had no cares or troubles of any sort, and every day her tasks became easier, and the years that had gone before seemed more and more like a bad dream. But the happier she grew the deeper was her wonder at everything around her, and the more firmly she was persuaded that some great unknown power must be at the bottom of it all.

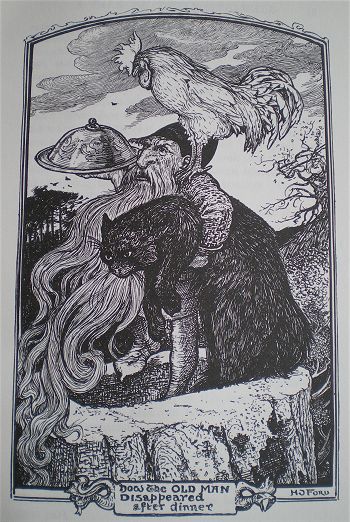

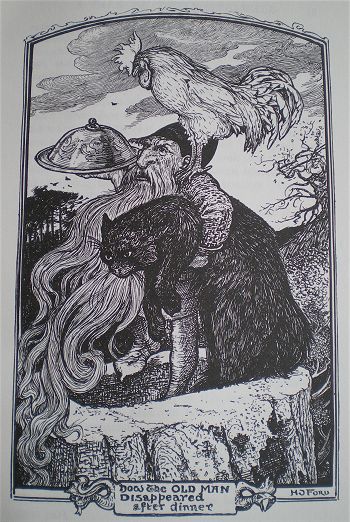

In the courtyard stood a huge granite block about twenty steps from the house, and when meal times came round the old man with the long beard went to the block, drew out a small silver staff, and struck the stone with it three times, so that the sound could be heard a long way off. At the third blow, out sprang a large golden cock, and stood upon the stone. Whenever he crowed and flapped his wings the rock opened and something came out of it. First a long table covered with dishes ready laid for the number of persons who would be seated round it, and this flew into the house all by itself.

When the cock crowed for the second time, a number of chairs appeared, and flew after the table; then wine, apples, and other fruit, all without trouble to anybody. After everybody had had enough, the old man struck the rock again. The golden cock crowed afresh, and back went dishes, table, chairs, and plates into the middle of the block.

When, however, it came to the turn of the thirteenth dish, which nobody ever wanted to eat, a huge black cat ran up, and stood on the rock close to the cock, while the dish was on his other side.

There they all remained, till they were joined by the old man.

He picked up the dish in one hand, tucked the cat under his arm, told the cock to get on his shoulder, and all four vanished into the rock. And this wonderful stone contained not only food, but clothes and everything you could possibly want in the house.

At first a language was often spoken at meals which was strange to Elsa, but by the help of the lady and her daughter she began slowly to understand it, though it was years before she was able to speak it herself.

One day she asked Kisika why the thirteenth dish came daily to the table and was sent daily away untouched, but Kisika knew no more about it than she did. The girl must, however, have told her mother what Elsa had said, for a few days later she spoke to Elsa seriously:

'Do not worry yourself with useless wondering. You wish to know why we never eat of the thirteenth dish? That, dear child, is the dish of hidden blessings, and we cannot taste of it without bringing our happy life here to an end. And the world would be a great deal better if men, in their greed, did not seek to snatch every thing for themselves, instead of leaving something as a thankoffering to the giver of the blessings. Greed is man's worst fault.'

The years passed like the wind for Elsa, and she grew into a lovely woman, with a knowledge of many things that she would never have learned in her native village; but Kisika was still the same young girl that she had been on the day of her first meeting with Elsa. Each morning they both worked for an hour at reading and writing, as they had always done, and Elsa was anxious to learn all she could, but Kisika much preferred childish games to anything else. If the humour seized her, she would fling aside her tasks, take her treasure box, and go off to play in the sea, where no harm ever came to her.

'What a pity,' she would often say to Elsa, 'that you have grown so big, you cannot play with me any more.'

Nine years slipped away in this manner, when one day the lady called Elsa into her room. Elsa was surprised at the summons, for it was unusual, and her heart sank, for she feared some evil threatened her. As she crossed the threshold, she saw that the lady's cheeks were flushed, and her eyes full of tears, which she dried hastily, as if she would conceal them from the girl. 'Dearest child,' she began, 'the time has come when we must part.'

'Part?' cried Elsa, burying her head in the lady's lap. 'No, dear lady, that can never be till death parts us. You once opened your arms to me; you cannot thrust me away now.'

'Ah, be quiet, child,' replied the lady; 'you do not know what I would do to make you happy. Now you are a woman, and I have no right to keep you here. You must return to the world of men, where joy awaits you.'

'Dear lady,' entreated Elsa again. 'Do not, I beseech you, send me from you. I want no other happiness but to live and die beside you. Make me your waiting maid, or set me to any work you choose, but do not cast me forth into the world. It would have been better if you had left me with my stepmother, than first to have brought me to heaven and then send me back to a worse place.'

'Do not talk like that, dear child,' replied the lady; 'you do not know all that must be done to secure your happiness, however much it costs me. But it has to be. You are only a common mortal, who will have to die one day, and you cannot stay here any longer. Though we have the bodies of men, we are not men at all, though it is not easy for you to understand why. Some day or other you will find a husband who has been made expressly for you, and will live happily with him till death separates you. It will be very hard for me to part from you, but it has to be, and you must make up your mind to it.' Then she drew her golden comb gently through Elsa's hair, and bade her go to bed; but little sleep had the poor girl! Life seemed to stretch before her like a dark starless night.

Now let us look back a moment, and see what had been going on in Elsa's native village all these years, and how her double had fared. It is a well-known fact that a bad woman seldom becomes better as she grows older, and Elsa's stepmother was no exception to the rule; but as the figure that had taken the girl's place could feel no pain, the blows that were showered on her night and day made no difference. If the father ever tried to come to his daughter's help, his wife turned upon him, and things were rather worse than before.

One day the stepmother had given the girl a frightful beating, and then threatened to kill her outright. Mad with rage, she seized the figure by the throat with both hands, when out came a black snake from her mouth and stung the woman's tongue, and she fell dead without a sound. At night, when the husband came home, he found his wife lying dead upon the ground, her body all swollen and disfigured, but the girl was nowhere to be seen. His screams brought the neighbours from their cottages, but they were unable to explain how it had all come about. It was true, they said, that about mid-day they had heard a great noise, but as that was a matter of daily occurrence they did not think much of it. The rest of the day all was still, but no one had seen anything of the daughter. The body of the dead woman was then prepared for burial, and her tired husband went to bed, rejoicing in his heart that he had been delivered from the firebrand who had made his home unpleasant. On the table he saw a slice of bread lying, and, being hungry, he ate it before going to sleep.

In the morning he too was found dead, and as swollen as his wife, for the bread had been placed in the body of the figure by the old man who made it. A few days later he was placed in the grave beside his wife, but nothing more was ever heard of their daughter.

All night long after her talk with the lady Elsa had wept and wailed her hard fate in being cast out from her home which she loved.

Next morning, when she got up, the lady placed a gold seal ring on her finger, strung a little golden box on a ribbon, and placed it round her neck; then she called the old man, and, forcing back her tears, took leave of Elsa. The girl tried to speak, but before she could sob out her thanks the old man had touched her softly on the head three times with his silver staff. In an instant Elsa knew that she was turning into a bird: wings sprang from beneath her arms; her feet were the feet of eagles, with long claws; her nose curved itself into a sharp beak, and feathers covered her body. Then she soared high in the air, and floated up towards the clouds, as if she had really been hatched an eagle.

For several days she flew steadily south, resting from time to time when her wings grew tired, for hunger she never felt. And so it happened that one day she was flying over a dense forest, and below hounds were barking fiercely, because, not having wings themselves, she was out of their reach. Suddenly a sharp pain quivered through her body, and she fell to the ground, pierced by an arrow.

When Elsa recovered her senses, she found herself lying under a bush in her own proper form. What had befallen her, and how she got there, lay behind her like a bad dream.

As she was wondering what she should do next the king's son came riding by, and, seeing Elsa, sprang from his horse, and took her by the hand, sawing, 'Ah! it was a happy chance that brought me here this morning. Every night, for half a year, have I dreamed, dear lady, that I should one day find you in this wood. And although I have passed through it hundreds of times in vain, I have never given up hope. To-day I was going in search of a large eagle that I had shot, and instead of the eagle I have found you.' Then he took Elsa on his horse, and rode with her to the town, where the old king received her graciously.

A few days later the wedding took place, and as Elsa was arranging the veil upon her hair fifty carts arrived laden with beautiful things which the lady of the Tontlawald had sent to Elsa. And after the king's death Elsa became queen, and when she was old she told this story. But that was the last that was ever heard of the Tontlawald.

(From Ehstnische Marchen.)

Una favola del Tontlawald

Tanto, tanto tempo fa in un paese costellato di laghi si trovava un vasto tratto di brughiera chiamato il Tontlawald nel quale nessun uomo osava mettere piede. Di tanto in tanto alcuni spiriti audaci erano attirati ai suoi confini dalla curiosità, e la ritorno riferivano di aver intravisto una casa in rovina in un folto boschetto, attorniata da creature simili a uomini che sciamavano come api sull'erba. Gli uomini erano sporchi e laceri come zingari e c'erano inoltre una quantità di vecchie e di bambini semi nudi

Una notte un contadino che stava ritornando a casa da un banchetto girovagò un poco oltre il Tontlawald e tornò indietro raccontando la stessa storia. Un'innumerevole quantità di donne e bambini erano radunati intorno a un enorme fuoco e alcuni erano seduti per terra mentre altri eseguivano strane danze sull'erba vellutata. Una vecchia megera teneva in mano un grande mestolo d'acciaio con il quale di quando in quando rimestava il fuoco, ma nel momento in cui toccò le ceneri ardenti, i bambini corsero via, strillando come gufi e ci volle un bel po' prima che si avventurassero a ritornare furtivamente. Oltre a tutto ciò era stato veduto una o due volte un vecchio ometto con una lunga barba che avanzava quatto quatto dalla foresta, trasportando un sacco più grande di lui. La donna e i bambini gli corsero accanto, piangendo e tentando di trascinare il sacco giù dalla sua schiena, ma lui se li scrollò di dosso e continuò la propria strada. Si narrava anche la storia di un magnifico gatto nero, grande come un puledro, ma gli uomini non avrebbero potuto credere a tutte le meraviglie raccontate dal contadino ed era difficile ricavare che cosa ci fosse di vero e di falso nella sua storia. Comunque resta il fatto che là accaddero strane cose e il Re di Svezia, al quale apparteneva quella parte di territorio, più di una volta diede ordine di abbattere il bosco infestato, ma non c'era nessuno che avesse abbastanza coraggio per obbedire ai suoi ordini. Alla fine un uomo, più audace degli altri, conficcò la scure in un albero, ma al suo colpo seguirono un fiume di sangue e urla simili a quelle di una creatura che soffriva. L'atterrito boscaiolo scappò quanto più in fretta gli consentirono le sue gambe e dopo di ciò né ordini né minacce avrebbero potuto condurre nessuno nella brughiera stregata.

A poche miglia dal Tontlawald c'era un grande villaggio in cui viveva un contadino che aveva sposato da poco una giovane donna. Come non è raro che accada in casi del genere, lei buttava all'aria l'intera casa e i due litigavano e si scontravano tutto il giorno.

Dalla prima moglie il contadino aveva avuto una figlia che si chiamava Elsa, una ragazza tranquilla che desiderava solo vivere in pace, ma con la sua matrigna ciò non era possibile. Ella picchiava e schiaffeggiava la povera bambina dal mattino alla sera, e siccome aveva il sopravvento sul marito non c'era rimedio.

Per due anni Elsa patì questo crudele trattamento finché un giorno uscì con altri bambini del villaggio per andare a raccogliere fragole. Incautamente gironzolarono finché raggiunsero il confine del Tontlawald, dove crescevano le più belle fragole che punteggiavano di rosso l'erba con i loro colori. I bambini si buttarono per terra e, dopo aver mangiato quanto potevano, cominciarono a riempire i loro cestini quando improvvisamente uno dei bambini più grandi gridò:

"Correte, correte più in fretta che potete! Siamo nel Tontlawald!"

Più veloci del lampo balzarono in piedi e corsero via come matti, tutti eccetto Elsa, che si era allontanata più degli altri e aveva trovato una distesa di bellissime fragole proprio sotto un albero. Come gli altri aveva udito il grido del bambino ma non si persuadeva a lasciare le fragole.

"Dopotutto che importa?" pensò. "Chi vive nel Tontlawald non può essere peggiore della mia matrigna." E sollevando lo sguardo vide un cagnolino nero con una campana d'argento al collo, il quale veniva verso di lei seguito da una fanciulla vestita di seta.

"Stai tranquilla," disse ella, poi girandosi verso Elsa, aggiunse:"Sono così contenta che tu non sia corsa via con gli altri fanciulli. Stai qui con me, diventa mia amica e faremo deliziosi giochi insieme, e ogni giorno andremo e raccoglieremo fragole. Nessuno oserà picchiarti se io dico di no. Vieni, andiamo da mia madre." E prendendo la mano di Elsa la condusse nel più folto del bosco, con il cagnolino nero che saltellava accanto a loro e abbaiava contento.

Quali meraviglie e splendori si svelarono agli occhi sbalorditi di Elsa! Pensava davvero di essere giunta in Paradiso. Davanti a loro sorgevano alberi da frutta e cespugli carichi mentre fra i rami stavano uccelli, più vivaci delle farfalle più splendide,e riempivano l'aria con i loro canti. E non erano diffidenti, ma lasciavano che le fanciulle li prendessero in mano e accarezzassero le loro piume d'oro e d'argento. In mezzo al giardino sorgeva la dimora, scintillante come cristallo e pietre preziose, e sulla soglia c'era una donna in ricche vesti che si rivolse alla compagna di Elsa e chiese:

"Che specie di ospite mi stai portando?"

"L'ho trovata sola nel bosco", replicò la figlia, "e l'ho portata con me come compagna. Lascerai che rimanga qui?"

La madre rise, ma non disse nulla, la squadrò solo dall'alto in basso. Poi disse alla ragazza di avvicinarsi, le accarezzò una guancia e le parlò cortesemente, chiedendole dove vivessero i suoi genitori e se davvero le piaceva stare con loro. Elsa s'inchinò e le baciò la mano poi, inginocchiandosi, seppellì il viso in grembo alla donna e singhiozzò:

"Mia madre giace sottoterra da molti anni. Mio padre è ancora vivo, ma non sono niente per lui, e la mia matrigna mi picchia tutto il giorno. Non ne faccio una giusta perciò, vi prego, lasciatemi stare con voi. Pascolerò le greggi o farò qualunque altro lavoro mi chiederete; obbedirò a qualsiasi cosa mi direte, solo, vi scongiuro, non rimandatemi da lei. Sarebbe quasi capace di uccidermi per non essere tornata con gli altri bambini." La donna sorrise e rispose:"Beh, vedremo che cosa fare di te" e, alzandosi, entrò in casa.

Allora la figlia disse a Elsa, "Non temere, mia madre ti sarà amica. A proposito, ho notato che sembrava propensa a esaudire la tua richiesta dopo averci pensato un po' su", e dicendo a Elsa di aspettare, entrò in casa a cercare sua madre. Elsa intanto era combattuta tra speranza e timore e sentiva che la ragazza non sarebbe più tornata.

Alla fine Elsa la vide che attraversava l'erba con una scatola in mano.

"Mia madre dice che oggi possiamo giocare insieme, mentre vuole decidere che cosa fare di te. Io spero che tu stia qui sempre, perché non potrei sopportare che tu vada via. Sei mai stata sul mare?

"Il mare?" chiese Elsa, fissandola; "Che cos'è? Non ne ho mai sentito parlare."

"Oh, te lo mostrerò presto", rispose la ragazza, levando il coperchio dalla scatola che sul fondo conteneva un brandello di un manto, una valva di cozza e due squame di pesce. Due gocce d'acqua scintillavano sul manto e la ragazza le sparse sul terreno. In un attimo il giardino, il prato e ogni altra cosa svanirono completamente, come se la terra si fosse aperta e li avesse inghiottiti, e fin dove gli occhi potevano arrivare non avresti visto altro che acqua, la quale sembrava toccasse il cielo stesso. Solo sotto i loro piedi c'era un minuscolo lembo asciutto. Allora la ragazza collocò la valva di cozza sull'acqua e prese in mano le squame di pesce. La valva diventò sempre più grande e si trasformò in una graziosa barchetta che avrebbe potuto contenere una dozzina di bambini. La ragazza vi salì, Elsa con molta cautela perché era molto divertita dalla sua amica che usava le squame di pesce come timone. Le onde dondolavano delicatamente le ragazze come se fossero adagiate in una culla e navigarono finché incontrarono altre barche pieni di uomini che cantavano e facevano festa.

"Dobbiamo cantarvi una canzone in cambio", disse la ragazza, ma siccome Elsa non conosceva nessuna canzone, dovette cantare da sola. Elsa non riusciva a capire nessuna delle canzoni degli uomini, ma notò che una parola si ripeteva in continuazione, ed era 'Kisika'. Elsa chiese che cosa significasse e la ragazza replicò che era il suo nome.

Fu tutto così piacevole che sarebbero potute restare lì per sempre se non ci fosse stata una voce che gridava loro "Bambine, per voi è ora di tornare a casa!"

Così Kisika prese la scatoletta dalla borsa, con il brandello di stoffa che conteneva, lo immerse nell'acqua ed ecco! si ritrovarono vicino a una splendida casa in mezzo a un giardino. Ogni cosa intorno a loro era asciutta e solida, e non c'era acqua da nessuna parte. La valva di cozza e le squame di pesce furono riposte nella scatola e le ragazze entrarono.

Si trovarono in un grande atrio in cui ventiquattro donne riccamente abbigliate sedevano intorno a un tavolo come se fossero a una festa di nozze. A capotavola c'era la padrona di casa su una sedia dorata.

Elsa non sapeva dove guardare perché qualunque cosa incontrasse il suo sguardo era più bella di quanto avrebbe creduto possibile. Tuttavia sedette con le altre, mangiò dei frutti deliziosi e pensò di essere in paradiso. Le ospiti parlavano a voce bassa, ma in una lingua sconosciuta a Elsa, che non capiva nulla di ciò che dicevano. Allora la padrona di casa si girò e sussurrò qualcosa alla serva dietro la sua sedia; la serva lasciò la sala e, quando tornò indietro, condusse con sé un ometto anziano con una barba più lunga di lui. S'inchinò profondamente alla dama e poi rimase tranquillamente vicino alla porta.

"Vedi questa ragazza?" disse la padrona di casa, indicando Elsa. "Desidero adottarla come figlia. Creane una copia che io possa mandare al villaggio natale al posto suo.

Il vecchio squadrò Elsa da cima a fondo, come se le stesse prendendo le misure, s'inchinò di nuovo alla dama e lasciò la sala. Dopo cena la dama disse gentilmente a Elsa, "Kisika mi ha pregata di lasciarti rimanere qui con lei e tu hai detto che ti piacerebbe vivere qui, è così?"

A quelle parole Elsa cadde sulle ginocchia e baciò con gratitudine le mani e i piedi della dama perché le permetteva di sfuggire alla crudele matrigna, ma la sua ospite la sollevò da terra e le accarezzò la testa, dicendo, "Tutto andrà bene finché sarai una ragazza buona e obbediente, mi prenderò cura di te e provvederò a ciò che vuoi senza ricompensa finché sarai cresciuta e potrai badare a te stessa. La mia cameriera, che ha insegnato a Kisika ogni sorta di bei lavori manuali, insegnerà anche a te".

Poco tempo dopo il vecchio tornò con uno stampo pieno di argilla sulle spalle e un cestino coperto nella mano sinistra. Depose a terra lo stampo e il cestino, prese una manciata di argilla e fece inaspettatamente una bambola. Quando ebbe finito fece un buco nel petto della bambola e vi mise un pezzetto di pane, poi, estraendo un serpente dal cestino, lo costrinse a entrare nel corpo vuoto.

"Adesso", disse alla dama, "tutto ciò che occorre è una goccia di sangue della fanciulla."

Quando sentì ciò, Elsa impallidì per l'orrore, perché pensò che stava vendendo l'anima al diavolo.

"Non temere!" si affrettò a dire la dama, "Non vogliamo il tuo sangue per qualche scopo malefico, ma piuttosto per darti libertà e felicità ".

Allora prese un minuscolo ago d'oro, punse Elsa sul braccio e diede l'ago al vecchio, che lo conficcò nel cuore della bambola. Fatto ciò, collocò la figura nel cestino, promettendo che il giorno dopo avrebbero visto che meraviglioso compito avesse svolto.

Quando Elsa si svegliò la mattina seguente nel proprio letto di seta, con soffici guanciali bianchi, vide un meraviglioso abito appoggiato sul dorso della sedia, pronto perché lo indossasse. Una cameriera venne a pettinarle i lunghi capelli e portò la biancheria più fine per lei, ma nulla rese Elsa tanto felice come il piccolo paio di scarpe ricamate che teneva in mano, perché fino ad allora la sua matrigna l'aveva obbligata a correre scalza. Nell'eccitazione non si preoccupò più delle rozze scarpe che aveva indossato il giorno prima e che erano sparite per magia durante la notte. Chi poteva averle prese? Bene, lo avrebbe saputo tra breve. Ma noi possiamo supporre che le avesse indossate la bambola, che doveva tornare indietro al villaggio al posto suo. Quando il sole era sorto la bambola aveva raggiunto la giusta taglia e nessuno avrebbe potuto distinguere una ragazza dall'altra. Elsa fece un balzo all'indietro quando incontrò se stessa come appariva appena ieri.

"Non devi spaventarti", disse la dama, quando si accorse del suo terrore, "Questa figura di argilla non può farti alcun danno. È per la tua matrigna, che potrà picchiarla al posto tuo. Lascia che la colpisca tanto duramente quanto vorrà, non può sentire alcun male. E se la malvagia donna non scenderà un giorno a più miti propositi, la tua copia sarà in grado di darle infine la punizione che merita".

Da quel momento la vita di Elsa fu quella di qualsiasi bambino felice, che nella propria infanzia fosse stato trastullato per addormentarsi in una graziosa culla d'oro. Non ebbe preoccupazioni o tribolazioni di qualunque tipo, ogni giorno i suoi compiti diventavano più facili e gli anni passati sembravano sempre più un brutto sogno. Ma più cresceva felice, più si faceva profonda la sua meraviglia per tutto ciò che la circondava, e ancor più fermamente si persuadeva che una sorta di grande potere sconosciuto fosse all'origine di tutto.

Nel cortile c'era un enorme blocco di granito a circa venti passi dalla casa e quando era l'ora dei pasti il vecchio con la lunga barba andava vicino al blocco, estraeva un bastoncino d'argento e percuoteva la pietra tre volte, così che il suono si poteva udire molto lontano. Al terzo colpo balzava fuori un grande gallo d'oro e stava sulla pietra. Ogni volta che cantava e sbatteva le ali, la roccia si apriva e ne usciva qualcosa. Dapprima una lunga tavola apparecchiata con piatti pronti per il numero di persone che vi si sarebbero sedute attorno, e che volava dentro la casa da solo.

Quando il gallo cantò per la seconda volta, apparve una certa quantità di sedie e volarono dietro il tavolo, poi vino, mele e altri frutti, tutto senza disturbo per nessuno. Dopo che tutti ne avevano avuto abbastanza, il vecchio percuoteva di nuovo la roccia. Il gallo d'oro cantava da capo e piatti, tavolo, sedie e stoviglie tornavano dentro la roccia.

Comunque, quando fu il turno del tredicesimo piatto, nel quale nessuno aveva voluto mangiare, un enorme gatto nero salì di corsa sulla roccia vicino al gallo mentre il piatto gli stava all'altro lato.

Rimasero tutti lì, finché furono raggiunti dal vecchio.

Egli prese il piatto in una mano, mise sottobraccio il gatto, disse al gallo di salirgli sulla spalla e tutti e quattro svanirono nella roccia. E questa pietra meravigliosa conteneva non solo cibo, ma abiti e qualunque cosa potreste volere in casa.

In principio spesso la lingua parlata durante i pasti era incomprensibile per Elsa, ma con l'aiuto della dama e di sua figlia piano piano la comprese benché ci vollero anni prima che fosse capace di parlarla.

Un giorno chiese a Kisika perché il tredicesimo piatto compariva ogni giorno sulla tavola ed era restituito ogni giorno intatto, ma Kisika non ne sapeva più di lei. La ragazza, comunque, raccontò a sua madre ciò che Elsa aveva detto, per cui alcuni giorni più tardi ella parlò con Elsa molto seriamente.

"Non angustiarti con vane domande. Vuoi sapere perché non mangiamo mai nel tredicesimo piatto? Quello, cara bambina, è il piatto delle benedizioni segrete e non possiamo gustarlo senza porre fine alla nostra felice vita qui. Il mondo sarebbe assai migliore se gli uomini, nella loro avidità, non cercassero di arraffare tutto per sé invece di offrire qualcosa in sacrificio a colui che dispensa benedizioni. L'avidità è il peggior difetto dell'uomo.

Gli anni passarono come il vento per Elsa e diventò una bella donna. Con un bagaglio di conoscenze che non avrebbe mai appreso nel suo villaggio natale., ma Kisika era sempre la stessa ragazzina del giorno del primo incontro con Elsa. Ogni mattina entrambe si dedicavano per un'ora alla lettura e alla scrittura come avevano sempre fatto, e Elsa era avida di imparare tutto ciò che potesse, ma Kisika preferiva i giochi infantili a qualunque altra cosa. Se era dell'umore giusto, poteva accantonare i compiti, prendere la sua scatola del tesoro e scappare a giocare sul mare, dove non correva nessun pericolo.

"Che peccato" diceva spesso a Elsa, "che tu sia diventata troppo grande e non possa più giocare con me."

Nove anni scivolarono via in questo modo, quando un giorno la dama chiamò Elsa nella propria stanza. Elsa si sorprese a quella chiamata, che era insolita, e il suo cuore sprofondò perché temeva che qualcosa di male la minacciasse. Come oltrepassò la soglia, vide che la dama aveva le guance arrossate e gli occhi pieni di lacrime, che asciugò in fretta come se avesse voluto nasconderle alla ragazza. "Mia cara bambina", incominciò, "è tempo che ci separiamo."

"Separarci?" gridò Elsa, nascondendo la testa nel grembo della dama. "No, cara signora, neppure la morte potrà separarci. Mi avete spalancato le braccia, non potete respingermi ora?"

"Ah, stai tranquilla, bambina" replicò la dama, "non sa che cosa farei per renderti felice. Ora sei una donna e non ho il diritto di trattenerti qui. Devi tornare nel mondo degli uomini in cui la gioia ti aspetta."

"Cara signora", supplicò di nuovo Elsa, "Vi imploro, non allontanatemi da voi. Non voglio altra felicità che vivere e morire accanto a voi. Fate di me la vostra cameriera o affidatemi qualunque lavoro scegliate, ma non sospingetemi di nuovo nel mondo. Sarebbe stato meglio se mi aveste lasciata con la mia matrigna, piuttosto che avermi prima condotta in paradiso e poi rispedirmi in un luogo peggiore."

"Non dire così, cara bambina" replicò la dama, " tu non sai quanto è stato fatto per garantirti la felicità, per quanto mi costi. Ma così deve essere. Sei solo una comune mortale, che un giorno dovrà morire, e non puoi stare qui più a lungo. Benché abbiamo corpi di uomini, non siamo completamente umani, per quanto non sia facile per te comprendere il perché. Un giorno o l'altro troverai un marito fatto apposta per te e vivrai felicemente con lui finché la morte vi separi. È molto duro per me separarmi da te, ma così deve essere, e tu devi deciderti a farlo". Poi passò delicatamente il pettine d'oro tra i capelli di Elsa e la invitò ad andare a letto, ma che breve sonno ebbe la povera ragazza! Le sembrò che la vita si stendesse davanti a lei come una cupa notte priva di stelle.

Adesso lasciate che torniamo indietro un momento, vediamo che cosa è accaduto nel villaggio natale di Elsa in tutti questi anni e come se l'è cavata la sua copia. È risaputo che una donna cattiva raramente migliora diventando vecchia, e la matrigna di Elsa non fece eccezione; ma siccome la copia che aveva preso il posto della ragazza non poteva sentire dolore, i colpi che cadevano giorno e notte su di lei la lasciavano indifferente. Se mai il padre tentava di venire in aiuto della figlia, sua moglie prendeva il sopravvento su di lui e le cose andavano peggio di prima.

Un giorno la matrigna l'aveva picchiata in maniera orribile e addirittura minacciato di ucciderla. Folle di rabbia, aveva afferrato la figura per la gola con entrambe le mani, quando un serpente nero venne fuori dalla bocca e morsicò la lingua della donna, che cadde morta senza un suono. Di notte, quando suo marito tornò a casa, trovò la moglie che giaceva morta sul pavimento, il corpo gonfio e sfigurato, ma la ragazza non si vedeva da nessuna parte. Le sue grida fecero uscire di casa i vicini, che non furono in grado di spiegare come il tutto fosse accaduto. Era vero, dissero, che verso mezzogiorno avevano sentito un gran rumore, ma era cosa di tutti i giorni e non ci avevano fatto troppo caso. Il resto della giornata fu tranquillo, ma nessuno aveva visto traccia della figlia. Il corpo della morta fu preparato per il funerale e il marito spossato andò a letto, rallegrandosi in cuor proprio di essere stato liberato da colei che aveva reso sgradevole la sua casa. Sulla tavola vide una fetta di pane e, sentendosi affamato, la mangiò prima di andare a dormire.

La mattina fu trovato morto, e gonfio come la moglie, per colpa del pane che era stato collocato nel corpo della figura dal vecchio che l'aveva modellata. Alcuni giorni più tardi fu deposto nella tomba accanto alla moglie, ma nessuno aveva sentito più nulla della figlia.

Per tutta la notte dopo il colloquio con la dama Elsa aveva pianto e si era lagnata del duro destino che la voleva lontana dalla casa che amava.

Il mattino successivo, quando si alzò, la dama le infilò al dito un anello d'oro con sigillo, legò con un nastro una scatoletta d'oro e gliela mise al collo; poi chiamò il vecchio e, ricacciando indietro le lacrime, si separò da Elsa. La ragazza cercò di parlare, ma prima che potesse esprimere tra i singhiozzi i propri ringraziamenti, il vecchio la toccò delicatamente tre volte sulla testa con il suo bastone d'argento. In un attimo Elsa capì di essere stata trasformata in un uccello, le ali spuntarono da sotto le braccia; i piedi divennero zampe di aquila dai lunghi artigli; il naso s'incurvò in un becco affilato e le piume coprirono il suo corpo. Allora si sollevò in aria, e fluttò tra le nuvole come se realmente fosse nata aquila.

Per vari giorni volò costantemente a sud, riposando di volta in volta quando le ali erano stanche, perché non sentiva mai fame. E così avvenne che un giorno stesse volando su una fitta foresta e sotto i segugi stavano abbaiando ferocemente perché, non avendo essi le ali, era fuori della loro portata. Improvvisamente un dolore acuto le trapassò il corpo e cadde a terra, colpita da una freccia.

Quando Elsa riprese i sensi, si ritrovò sotto un cespuglio con il proprio aspetto. Ciò che le era accaduto e come fosse arrivata lì le sembrò un brutto sogno.

Mentre si domandava che cosa avrebbe fatto, il figlio del re arrivò cavalcando e, vedendo Elsa, balzò da cavallo e la prese per mano, dicendo, "Ah, è una felice circostanza che mi ha condotto qui stamattina. Ogni notte, per sei mesi, ho sognato, mia cara dama, che un giorno vi avrei trovata in questa foresta. Sebbene vi sia passato centinaia di volte invano, non ho mai perso la speranza. Oggi stavo cercando una grande aquila che avevo colpito e invece dell'aquila ho trovato voi." Quindi fece salire in sella Elsa e cavalcò con lei in città, dove l'anziano re la ricevette cortesemente.

Alcuni giorni più tardi avvennero le nozze e appena Elsa sistemò il velo sui capelli, arrivarono cinquanta carrette cariche di cose meravigliose che la dama del Tontlawald le aveva mandato. E dopo la morte del re Elsa diventò regina, e quando fu vecchia narrò questa storia. E fu l'ultima a essere mai udita sul Tontlawald.

Da Ehstnische Marchen.

È una storia estone raccolta da Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (Scrittore e medico estone, 1803-82) in Eestirahwa Ennemuistesed jutud. William Forsell Kirby (entomologo e folklorista inglese, 1844-1912) l'ha inclusa con il titolo The Wood of Tontla nella raccolta The Hero of Esthonia.Questa di Andrew Lang è la traduzione della versione tedesca Der Tontlawald fatta da Ferdinand Löwe. (riferita sempre alla raccolta di Kreutzwald)

Qui il collegamento alla pagina in inglese dedicata a questa favola su Wikipedia

Qui un poema dedicato all'eroina della favola

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)