The Nine Pea-Hens and the Golden Apples

(20'12'')

Once upon a time there stood before the palace of an emperor a golden apple tree, which blossomed and bore fruit each night. But every morning the fruit was gone, and the boughs were bare of blossom, without anyone being able to discover who was the thief.

At last the emperor said to his eldest son, 'If only I could prevent those robbers from stealing my fruit, how happy I should be!'

And his son replied, 'I will sit up to-night and watch the tree, and I shall soon see who it is!'

So directly it grew dark the young man went and hid himself near the apple tree to begin his watch, but the apples had scarcely begun to ripen before he fell asleep, and when he awoke at sunrise the apples were gone. He felt very much ashamed of himself, and went with lagging feet to tell his father!

Of course, though the eldest son had failed, the second made sure that he would do better, and set out gaily at nightfall to watch the apple tree. But no sooner had he lain himself down than his eyes grew heavy, and when the sunbeams roused him from his slumbers there was not an apple left on the tree.

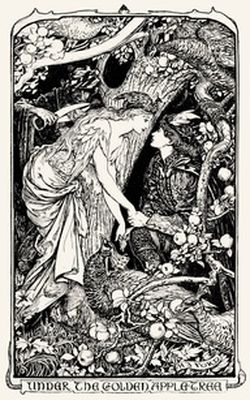

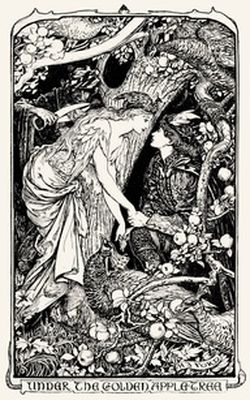

Next came the turn of the youngest son, who made himself a comfortable bed under the apple tree, and prepared himself to sleep. Towards midnight he awoke, and sat up to look at the tree. And behold! the apples were beginning to ripen, and lit up the whole palace with their brightness. At the same moment nine golden pea-hens flew swiftly through the air, and while eight alighted upon the boughs laden with fruit, the ninth fluttered to the ground where the prince lay, and instantly was changed into a beautiful maiden, more beautiful far than any lady in the emperor's court. The prince at once fell in love with her, and they talked together for some time, till the maiden said her sisters had finished plucking the apples, and now they must all go home again. The prince, however, begged her so hard to leave him a little of the fruit that the maiden gave him two apples, one for himself and one for his father. Then she changed herself back into a pea-hen, and the whole nine flew away.

As soon as the sun rose the prince entered the palace, and held out the apple to his father, who was rejoiced to see it, and praised his youngest son heartily for his cleverness. That evening the prince returned to the apple tree, and everything passed as before, and so it happened for several nights. At length the other brothers grew angry at seeing that he never came back without bringing two golden apples with him, and they went to consult an old witch, who promised to spy after him, and discover how he managed to get the apples. So, when the evening came, the old woman hid herself under the tree and waited for the prince. Before long he arrived and laid down on his bed, and was soon fast asleep. Towards midnight there was a rush of wings, and the eight pea-hens settled on the tree, while the ninth became a maiden, and ran to greet the prince. Then the witch stretched out her hand, and cut off a lock of the maiden's hair, and in an instant the girl sprang up, a pea-hen once more, spread her wings and flew away, while her sisters, who were busily stripping the boughs, flew after her.

When he had recovered from his surprise at the unexpected disappearance of the maiden, the prince exclaimed, 'What can be the matter?' and, looking about him, discovered the old witch hidden under the bed. He dragged her out, and in his fury called his guards, and ordered them to put her to death as fast as possible. But that did no good as far as the pea-hens went. They never came back any more, though the prince returned to the tree every night, and wept his heart out for his lost love. This went on for some time, till the prince could bear it no longer, and made up his mind he would search the world through for her. In vain his father tried to persuade him that his task was hopeless, and that other girls were to be found as beautiful as this one. The prince would listen to nothing, and, accompanied by only one servant, set out on his quest.

After travelling for many days, he arrived at length before a large gate, and through the bars he could see the streets of a town, and even the palace. The prince tried to pass in, but the way was barred by the keeper of the gate, who wanted to know who he was, why he was there, and how he had learnt the way, and he was not allowed to enter unless the empress herself came and gave him leave. A message was sent to her, and when she stood at the gate the prince thought he had lost his wits, for there was the maiden he had left his home to seek. And she hastened to him, and took his hand, and drew him into the palace. In a few days they were married, and the prince forgot his father and his brothers, and made up his mind that he would live and die in the castle.

One morning the empress told him that she was going to take a walk by herself, and that she would leave the keys of twelve cellars to his care. 'If you wish to enter the first eleven cellars,' said she, 'you can; but beware of even unlocking the door of the twelfth, or it will be the worse for you.'

The prince, who was left alone in the castle, soon got tired of being by himself, and began to look about for something to amuse him.

'What CAN there be in that twelfth cellar,' he thought to himself, 'which I must not see?' And he went downstairs and unlocked the doors, one after the other. When he got to the twelfth he paused, but his curiosity was too much for him, and in another instant the key was turned and the cellar lay open before him. It was empty, save for a large cask, bound with iron hoops, and out of the cask a voice was saying entreatingly, 'For goodness' sake, brother, fetch me some water; I am dying of thirst!'

The prince, who was very tender-hearted, brought some water at once, and pushed it through a hole in the barrel; and as he did so one of the iron hoops burst.

He was turning away, when a voice cried the second time, 'Brother, for pity's sake fetch me some water; I'm dying of thirst!'

So the prince went back, and brought some more water, and again a hoop sprang.

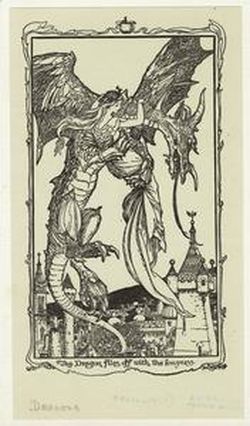

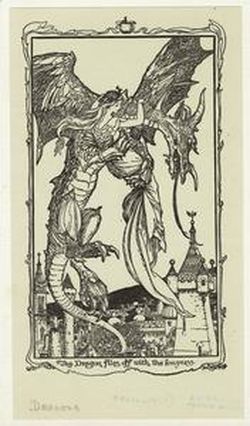

And for the third time the voice still called for water; and when water was given it the last hoop was rent, the cask fell in pieces, and out flew a dragon, who snatched up the empress just as she was returning from her walk, and carried her off. Some servants who saw what had happened came rushing to the prince, and the poor young man went nearly mad when he heard the result of his own folly, and could only cry out that he would follow the dragon to the ends of the earth, until he got his wife again.

For months and months he wandered about, first in this direction and then in that, without finding any traces of the dragon or his captive. At last he came to a stream, and as he stopped for a moment to look at it he noticed a little fish lying on the bank, beating its tail convulsively, in a vain effort to get back into the water.

'Oh, for pity's sake, my brother,' shrieked the little creature, 'help me, and put me back into the river, and I will repay you some day. Take one of my scales, and when you are in danger twist it in your fingers, and I will come!'

The prince picked up the fish and threw it into the water; then he took off one of its scales, as he had been told, and put it in his pocket, carefully wrapped in a cloth. Then he went on his way till, some miles further down the road, he found a fox caught in a trap.

'Oh! be a brother to me!' called the fox, 'and free me from this trap, and I will help you when you are in need. Pull out one of my hairs, and when you are in danger twist it in your fingers, and I will come.'

So the prince unfastened the trap, pulled out one of the fox's hairs, and continued his journey. And as he was going over the mountain he passed a wolf entangled in a snare, who begged to be set at liberty.

'Only deliver me from death,' he said, 'and you will never be sorry for it. Take a lock of my fur, and when you need me twist it in your fingers.' And the prince undid the snare and let the wolf go.

For a long time he walked on, without having any more adventures, till at length he met a man travelling on the same road.

'Oh, brother!' asked the prince, 'tell me, if you can, where the dragon-emperor lives?'

The man told him where he would find the palace, and how long it would take him to get there, and the prince thanked him, and followed his directions, till that same evening he reached the town where the dragon-emperor lived. When he entered the palace, to his great joy he found his wife sitting alone in a vast hall, and they began hastily to invent plans for her escape.

There was no time to waste, as the dragon might return directly, so they took two horses out of the stable, and rode away at lightning speed. Hardly were they out of sight of the palace than the dragon came home and found that his prisoner had flown. He sent at once for his talking horse, and said to him:

'Give me your advice; what shall I do—have my supper as usual, or set out in pursuit of them?'

'Eat your supper with a free mind first,' answered the horse, 'and follow them afterwards.'

So the dragon ate till it was past midday, and when he could eat no more he mounted his horse and set out after the fugitives. In a short time he had come up with them, and as he snatched the empress out of her saddle he said to the prince:

'This time I will forgive you, because you brought me the water when I was in the cask; but beware how you return here, or you will pay for it with your life.'

Half mad with grief, the prince rode sadly on a little further, hardly knowing what he was doing. Then he could bear it no longer and turned back to the palace, in spite of the dragon's threats. Again the empress was sitting alone, and once more they began to think of a scheme by which they could escape the dragon's power.

'Ask the dragon when he comes home,' said the prince, 'where he got that wonderful horse from, and then you can tell me, and I will try to find another like it.'

Then, fearing to meet his enemy, he stole out of the castle.

Soon after the dragon came home, and the empress sat down near him, and began to coax and flatter him into a good humour, and at last she said:

'But tell me about that wonderful horse you were riding yesterday. There cannot be another like it in the whole world. Where did you get it from?'

And he answered:

'The way I got it is a way which no one else can take. On the top of a high mountain dwells an old woman, who has in her stables twelve horses, each one more beautiful than the other. And in one corner is a thin, wretched-looking animal whom no one would glance at a second time, but he is in reality the best of the lot. He is twin brother to my own horse, and can fly as high as the clouds themselves. But no one can ever get this horse without first serving the old woman for three whole days. And besides the horses she has a foal and its mother, and the man who serves her must look after them for three whole days, and if he does not let them run away he will in the end get the choice of any horse as a present from the old woman. But if he fails to keep the foal and its mother safe on any one of the three nights his head will pay.'

The next day the prince watched till the dragon left the house, and then he crept in to the empress, who told him all she had learnt from her gaoler. The prince at once determined to seek the old woman on the top of the mountain, and lost no time in setting out. It was a long and steep climb, but at last he found her, and with a low bow he began:

'Good greeting to you, little mother!'

'Good greeting to you, my son! What are you doing here?'

'I wish to become your servant,' answered he.

'So you shall,' said the old woman. 'If you can take care of my mare for three days I will give you a horse for wages, but if you let her stray you will lose your head'; and as she spoke she led him into a courtyard surrounded with palings, and on every post a man's head was stuck. One post only was empty, and as they passed it cried out:

'Woman, give me the head I am waiting for!'

The old woman made no answer, but turned to the prince and said:

'Look! all those men took service with me, on the same conditions as you, but not one was able to guard the mare!'

But the prince did not waver, and declared he would abide by his words.

evening came he led the mare out of the stable and mounted her, and the colt ran behind. He managed to keep his seat for a long time, in spite of all her efforts to throw him, but at length he grew so weary that he fell fast asleep, and when he woke he found himself sitting on a log, with the halter in his hands. He jumped up in terror, but the mare was nowhere to be seen, and he started with a beating heart in search of her. He had gone some way without a single trace to guide him, when he came to a little river. The sight of the water brought back to his mind the fish whom he had saved from death, and he hastily drew the scale from his pocket. It had hardly touched his fingers when the fish appeared in the stream beside him.

'What is it, my brother?' asked the fish anxiously.

'The old woman's mare strayed last night, and I don't know where to look for her.'

'Oh, I can tell you that: she has changed herself into a big fish, and her foal into a little one. But strike the water with the halter and say, "Come here, O mare of the mountain witch!" and she will come.'

The prince did as he was bid, and the mare and her foal stood before him. Then he put the halter round her neck, and rode her home, the foal always trotting behind them. The old woman was at the door to receive them, and gave the prince some food while she led the mare back to the stable.

'You should have gone among the fishes,' cried the old woman, striking the animal with a stick.

'I did go among the fishes,' replied the mare; 'but they are no friends of mine, for they betrayed me at once.'

'Well, go among the foxes this time,' said she, and returned to the house, not knowing that the prince had overheard her.

So when it began to grow dark the prince mounted the mare for the second time and rode into the meadows, and the foal trotted behind its mother. Again he managed to stick on till midnight: then a sleep overtook him that he could not battle against, and when he woke up he found himself, as before, sitting on the log, with the halter in his hands. He gave a shriek of dismay, and sprang up in search of the wanderers. As he went he suddenly remembered the words that the old woman had said to the mare, and he drew out the fox hair and twisted it in his fingers.

'What is it, my brother?' asked the fox, who instantly appeared before him.

'The old witch's mare has run away from me, and I do not know where to look for her.'

'She is with us,' replied the fox, 'and has changed herself into a big fox, and her foal into a little one, but strike the ground with a halter and say, "Come here, O mare of the mountain witch!"'

The prince did so, and in a moment the fox became a mare and stood before him, with the little foal at her heels. He mounted and rode back, and the old woman placed food on the table, and led the mare back to the stable.

'You should have gone to the foxes, as I told you,' said she, striking the mare with a stick.

'I did go to the foxes,' replied the mare, 'but they are no friends of mine and betrayed me.'

'Well, this time you had better go to the wolves,' said she, not knowing that the prince had heard all she had been saying.

The third night the prince mounted the mare and rode her out to the meadows, with the foal trotting after. He tried hard to keep awake, but it was of no use, and in the morning there he was again on the log, grasping the halter. He started to his feet, and then stopped, for he remembered what the old woman had said, and pulled out the wolf's grey lock.

'What is it, my brother?' asked the wolf as it stood before him.

'The old witch's mare has run away from me,' replied the prince, 'and I don't know where to find her.'

'Oh, she is with us,' answered the wolf, 'and she has changed herself into a she-wolf, and the foal into a cub; but strike the earth here with the halter, and cry, "Come to me, O mare of the mountain witch."'

The prince did as he was bid, and as the hair touched his fingers the wolf changed back into a mare, with the foal beside her. And when he had mounted and ridden her home the old woman was on the steps to receive them, and she set some food before the prince, but led the mare back to her stable.

'You should have gone among the wolves,' said she, striking her with a stick.

'So I did,' replied the mare, 'but they are no friends of mine and betrayed me.'

The old woman made no answer, and left the stable, but the prince was at the door waiting for her.

'I have served you well,' said he, 'and now for my reward.'

'What I promised that will I perform,' answered she. 'Choose one of these twelve horses; you can have which you like.'

'Give me, instead, that half-starved creature in the corner,' asked the prince. 'I prefer him to all those beautiful animals.'

'You can't really mean what you say?' replied the woman.

'Yes, I do,' said the prince, and the old woman was forced to let him have his way. So he took leave of her, and put the halter round his horse's neck and led him into the forest, where he rubbed him down till his skin was shining like gold. Then he mounted, and they flew straight through the air to the dragon's palace. The empress had been looking for him night and day, and stole out to meet him, and he swung her on to his saddle, and the horse flew off again.

Not long after the dragon came home, and when he found the empress was missing he said to his horse, 'What shall we do? Shall we eat and drink, or shall we follow the runaways?' and the horse replied, 'Whether you eat or don't eat, drink or don't drink, follow them or stay at home, matters nothing now, for you can never, never catch them.'

But the dragon made no reply to the horse's words, but sprang on his back and set off in chase of the fugitives. And when they saw him coming they were frightened, and urged the prince's horse faster and faster, till he said, 'Fear nothing; no harm can happen to us,' and their hearts grew calm, for they trusted his wisdom.

Soon the dragon's horse was heard panting behind, and he cried out, 'Oh, my brother, do not go so fast! I shall sink to the earth if I try to keep up with you.'

And the prince's horse answered, 'Why do you serve a monster like that? Kick him off, and let him break in pieces on the ground, and come and join us.'

And the dragon's horse plunged and reared, and the dragon fell on a rock, which broke him in pieces. Then the empress mounted his horse, and rode back with her husband to her kingdom, over which they ruled for many years.

Volksmarchen der Serben.

Le nove pavonesse e le mele d’oro

C’era una volta un albero di mele d’oro che cresceva davanti al palazzo al palazzo di un imperatore e che fioriva e dava frutti ogni notte. Ma ogni mattina un frutto era sparito e i rami erano privi di fiori senza che nessuno riuscisse a scoprire chi fosse il ladro.

Alla fine l’imperatore disse la figlio maggiore: “Se solo potessi impedire a quei ladri di rubare il mio frutto, come sarei felice!”

E suo figlio rispose: “Stanotte mi siederò e osserverò l’albero, e vedrò presto chi sia!”

Così appena fece buio il giovanotto andò e si nascose vicino al melo per cominciare la sorveglianza, ma le mele avevano appena incominciato a maturare prima che lui si addormentasse, e quando si svegliò all’alba le mele erano sparite. Si vergognò molto di se stesso e andò con passo lento a raccontarlo al padre!

Naturalmente, sebbene il maggiore avesse fallito, il secondo figlio fu certo che gli sarebbe andata meglio e al crepuscolo sedette allegramente a sorvegliare il melo. Ma dopo un po’ si sdraiò con gli occhi appesantiti e quando i raggi del sole lo svegliarono dal sonno, sull’albero non era rimasta una mela.

Poi fu il turno del figlio più giovane, che si preparò un comodo letto sotto il melo e si preparò a dormire. Intorno alla mezzanotte si svegliò e sedette a osservare l’albero. E guarda un po’! Le mele stavano cominciando a maturare e rischiaravano l’intero palazzo con la loro lucentezza. Nello stesso momento nove pavonesse volarono rapidamente nell’aria e mentre otto atterrarono sui rami carichi di frutti, la nona svolazzò sul terreno su cui stava il principe e all’istante fu trasformata in una meravigliosa ragazza, più bella di qualsiasi dama alla corte dell’imperatore. Il principe si innamorò subito di lei e parlarono per un po’ di tempo finché la ragazza disse che le sue sorelle avevano terminato di cogliere le mele e ora dovevano tornare tutte di nuovo a casa. Tuttavia il principe la pregò tanto intensamente di lasciarli un piccolo frutto che la ragazza gli diede due mele, una per lui e una per il padre. Poi si mutò di nuovo in una pavonessa e tutte e nove volarono via.

Appena il sole si levò, il principe entrò nel palazzo e offrì la mela al padre, il quale fu contento di vederla, e elogiò il figlio minore per la sua abilità. Quella sera il principe tornò presso il melo e tutto fu come la volta precedente, e così avvenne per diverse notti Alla fine gli altri fratelli si arrabbiarono vedendo che non tornava mai portando due mele d’oro per loro, e andarono a consultare una vecchia strega, che promise di spiarlo e di scoprire come riuscisse a ottenere le mele. Così, quando fu sera, la vecchia si nascose sotto l’albero e attese il principe. Ben presto arrivò e si distese sul letto, poi si addormentò profondamente. Verso mezzanotte ci fu un frullo d’ali e le otto pavonesse si posarono sull’albero, mentre la nona divenne una ragazza e corse a salutare il principe. Allora la strega allungò la mano e tagliò una ciocca dei capelli della ragazza; in un attimo la ragazza fece un balzo, di nuovo sotto forma di pavonessa, spiegò le ali e volò via, mentre le sue sorelle, che stavano spogliando laboriosamente i rami, volarono via dopo di lei.

Quando si riebbe dalla sorpresa per l’inattesa sparizione della ragazza, il principe esclamò: “Che cosa può essere stato?” e, guardandosi attorno, scoprì la vecchia strega nascosta sotto il letto. La trascinò fuori, e chiamò furibondo le guardie, ordinando loro di mandarla a morte il più presto possibile. Ma ciò non servì a far venire le pavonesse. Non tornarono indietro mai più, sebbene il principe tornasse sotto l’albero ogni notte e si struggesse il cuore per l’amore perduto. Fu così per diverso tempo, finché il principe non poté sopportarlo più a lungo e decise che sarebbe andato per il mondo in cerca di lei. Invano suo padre tentò di convincerlo che il suo compito era senza speranza, e che avrebbe trovato altre ragazze belle come quella. Il principe non volle ascoltare nulla e, accompagnato solo da un servitore, partì per la ricerca.

Dopo aver viaggiato per diversi giorni, arrivò infine davanti a un grande cancello, e attraverso le sbarre poteva vedere le strade di una città, e persino un palazzo. Il principe tentò di passare, ma la strada era sbarrata dai guardiani del cancello, che volevano sapere chi fosse, perché fosse lì, come avesse scoperto la strada, e non gli era concesso entrare a meno che l’imperatrice in persona venisse e gli desse il permesso. Le fu inviato un messaggio e quando fu al cancello il principe pensò di aver perso la ragione, perché era la ragazza per cercare la quale aveva lasciato la propria casa. Lei lo sollecitò, lo prese per mano e lo condusse nel palazzo. Nel giro di pochi giorni furono sposati e il principe dimenticò il padre e i fratelli e decise che sarebbe vissuto e morto nel castello.

Una mattina l’imperatrice gli disse che sarebbe andata a fare una passeggiata da sola e che gli avrebbe lasciato in custodia le chiavi di dodici sotterranei. Gli disse: “Se desideri entrare nei primi undici sotterranei, puoi farlo; ma bada bene di non aprire mai la porta del dodicesimo, o sarà peggio per te.”

Il principe, che era rimasto solo nel castello, ben presto si stanco di stare per conto proprio e cominciò a cercare qualcosa che lo distraesse.

”Che cosa può esserci mai nel dodicesimo sotterraneo che io non debba vedere?” pensò tra sé. Così scese al piano di sotto e aprì le porte, una dopo l’altra.. quando raggiunse la dodicesima porta, si fermò, ma la curiosità era insopportabile e un momento dopo la chiave fu girata e il sotterraneo era aperto davanti a lui. Era vuoto, all’infuori di una grossa botte, tenuta insieme da cerchi di ferro, e dalla botte una voce diceva supplichevole: “Per amor del cielo, fratello, vammi a prendere un poi’ d’acqua; sto morendo di sete!”

Il principe, che aveva un cuore buono, portò subito dell’acqua e la versò in un buco della botte; ma come l’ebbe fatto, uno dei cerchi di ferro si spezzò.

Stava per andarsene quando la voce gridò per la seconda volta: “Fratello, per carità, vammi a prendere un po’ d’acqua; sto morendo di sete!”

Così il principe tornò indietro e portò ancora un po’ d’acqua, e di nuovo un cerchio si spezzò. Per la terza volta la voce chiese di nuovo acqua, e quando l’acqua fu versata, l’ultimo cerchio si spezzò, la botte andò in pezzi e ne uscì un drago che ghermì l’imperatrice, proprio mentre era appena ritornata dalla passeggiata, e la portò via. Alcuni servi che avevano visto l’accaduto si gettarono sul principe, e il povero ragazzo quasi impazzì quando si rese conto del risultato della propria impresa, e poté solo gridare che avrebbe seguito il drago fino ai confini della terra, fino a riprendere sua moglie.

Vagabondò per mesi e mesi, dapprima in una direzione e poi nell’altra, senza trovare tracce del drago o della sua prigioniera. Infine giunse a un ruscello e siccome si era fermato per un momento a guardare, notò un pesciolino sulla riva, che sbatteva convulsamente la coda, e tentava invano di tornare in acqua.

La piccola creatura gridò: “Oh, per carità, fratello mio, aiutami e gettami di nuovo nel ruscello, un giorno ti ricompenserò. Prendi una delle mie squame e quando sarai in pericolo, avvolgitela sulle dita e io verrò!”

Il principe sollevò il pesce e lo gettò nell’acqua, poi prese una delle sue squame come gli aveva detto e la mise in tasca, avvolta con cura in una stoffa. Poi riprese la strada e alcune miglia più giù nella via trovò una volpe prigioniera di una trappola.

La volpe gridò: “Oh! Sii buono con me, liberami da questa trappola e io ti aiuterò quando ne avrai bisogno. Strappa uno dei miei peli e, quando sarai in pericolo, avvolgilo intorno alle dita, io verrò.”

Così il principe aprì la trappola, strappò uno dei peli della volpe e continuò il viaggio. Mentre stava per oltrepassare la montagna, superò un lupo intrappolato in un laccio, che lo pregò di restituirgli la libertà.

”Salvami dalla morte,” disse, “e non te ne pentirai mai. Prendi un ciuffo della mia pelliccia e, quando ne avrai bisogno, avvolgilo intorno alle dita.” E il principe sciolse il laccio e lasciò andare il lupo.

Camminò a lungo, senza vivere altre avventure, finché alla fine incontrò un uomo che percorreva la sua stessa strada.

”Oh, fratello!” chiese il principe, “dimmi, se puoi, dove vive l’imperatore dei draghi?”

L’uomo gli disse dove avrebbe trovato il palazzo e quanto gli sarebbe occorso per arrivare là, il principe lo ringraziò e seguì le sue istruzioni finché quella sera stessa arrivò nella città in cui viveva l’imperatore dei draghi. Quando entrò nel palazzo, con grande gioia trovò la moglie seduta da sola in un’ampia sala e si affrettarono a ideare un piano per la sua fuga.

Non c’era tempo da perdere, il drago sarebbe potuto ritornare entro poco tempo, così condussero fuori dalle stalle due cavalli e se ne andarono al galoppo con la velocità del lampo. Avevano appena perso di vista il palazzo che il drago tornò a casa e scoprì che la prigioniera era scappata. Mandò a chiamare il cavallo parlante e gli disse:

”Dammi il tuo parere; che cosa devo fare –cenare come il solito o uscire al loro inseguimento?”

”Prima cena a mente serena,” rispose il cavallo, “ e seguili più tardi.”

Così il drago mangiò fino a che fu trascorso mezzogiorno e quando non avrebbe più potuto mangiare nulla, montò a cavallo e inseguì i fuggitivi. In poco tempo li raggiunse e come ebbe strappato l’imperatrice dalla sella, disse al principe:

”Per questa volta ti perdono, perché mi hai dato l’acqua quando ero nella botte; ma bada bene di non tornare o la pagherai con la vita.”

Quasi pazzo di dolore, il principe cavalcò tristemente un poco oltre, sapendo a stento che cosa facesse. Poi non potendo sopportarlo più a lungo, tornò al palazzo, nonostante la minaccia del drago. Di nuovo l’imperatrice era seduta da sola, e ancora una volta cominciarono a pensare a un piano con il quale liberarsi dal dominio del drago.

Il principe disse: ”Quando il drago viene a casa, domandagli da dove venga quel magnifico cavallo e poi dimmelo, così io ne troverò uno simile.”

Poi, temendo di incontrare il nemico, uscì furtivamente dal castello.

Poco dopo il drago tornò a casa; l’imperatrice sedette accanto a lui e cominciò a lusingarlo e ad adularlo per metterlo di buonumore, poi alla fine disse:

”Parlami del meraviglioso cavallo che stavi cavalcando ieri. Non può essercene uno simile in tutto il mondo. Dove lo hai preso?”

E lui rispose:

La strada che ho seguito, nessun altro può percorrerla. In cima a un’alta montagna abita una vecchia, la quale ha nelle sue stalle dodici cavalli, ognuno dei quali è più splendido dell’altro. E in un angolo c’è un animale magro e sgraziato alla vista, che nessuno guarda per la seconda volta, ma in realtà è il migliore di tutti. È il gemello del mio cavallo più in alto delle nuvole. Ma nessuno può prendere questo cavallo senza prima aver servito la vecchia per tre giorni interi. E oltre al cavallo, ha un puledro e sua madre e l’uomo che la serve deve sorvegliarli per tre giorni interi, e se non li lascia scappare alla fine avrà la possibilità uno qualsiasi dei cavalli come dono da parte della vecchia. Ma se fallisce nel mantenere sani e salvi il puledro e sua madre anche una sola delle tre notti, pagherà con la testa.”

Il giorno seguente il principe tenne d’occhio il palazzo finché il drago se ne fu andato e poi entrò furtivamente dall’imperatrice, che gli raccontò tutto ciò che aveva appreso dal proprio carceriere. Il principe decise subito di andare in cerca della vecchia in cima alla montagna, e non perse tempo indugiando. Fu un’arrampicata lunga e ripida, ma infine la trovò e con un umile inchino incominciò:

”Salute a te, madrina!”

”Salute a te, figlio mio! Che cosa ci fai qui?”

”Desidero diventare tuo servitore.” rispose lui.

La vecchia disse: “E così sarà. Se potrai prenderti cura della mia giumenta per tre giorni, ti darò un cavallo come paga, ma se me la smarrisci, perderai la testa.” E dopo aver così parlato lo condusse in un cortile circondato di paletti, e su ognuno di essi era infilzata una testa d’uomo. Uno solo paletto era vuoto e quando passarono, gridò:

”Donna, dammi la testa che sto aspettando!”

La vecchia non rispose, ma si voltò verso il principe e disse:

”Guarda! Tutti quegli uomini mi hanno servita alle stesse tue condizioni, me nemmeno uno di loro è stato in grado di custodire la giumenta!”

Ma il principe non esitò e dichiarò che avrebbe tenuto fede alla parola data.

Quando scese la sera, condusse la giumenta fuori dalla stalla e la montò, e il puledro corse dietro. Riuscì a stare in sella per un bel po’, malgrado tutti i tentativi della giumenta di disarcionarlo, ma alla fine si sentì così stanco che si addormentò subito e quando si svegliò si ritrovò seduto su un ceppo con le briglie in mano. Balzò in piedi terrorizzato, ma la giumenta non si vedeva da nessuna parte, e con il cuore in gola cominciò a cercarla. Aveva seguito varie strade senza una sola traccia che lo guidasse quando giunse presso un fiumiciattolo. La vista dell’acqua gli rammentò il pesce che aveva salvato da morte certa e rapidamente estrasse la squama dalla borsa. L’aveva appena avvolta intorno al dito che il pesce comparve nel corso d’acqua accanto a lui.

”Che c’è, fratello?” chiese ansiosamente il pesce.

”La giumenta della vecchia si è allontanata la notte scorsa e non so dove cercarla.”

”Oh, posso dirtelo io: si è trasformata in un grosso pesce e il suo puledro in uno piccolo. Ma tu colpisci l’acqua con le briglie e di’: ‘Vieni qui, giumenta della strega della montagna!’ e lei verrà.”

Il principe fece come gli era stato ordinato e la giumenta e il puledro furono davanti a lui. Allora le mise le redini al collo e la guidò a casa, il puledrino che trottava dietro di loro. La vecchia era sulla porta ad accoglierli e diede al principe un po’ di cibo mentre lei conduceva la giumenta nella stalla.

”Saresti dovuta andare in mezzo ai pesci,” gridò la vecchia, colpendo l’animale con un bastone.

“Sono andata tra i pesci,” replicò la giumenta; “ma non erano miei amici perché mi hanno subito tradita.”

”Ebbene, la prossima volta vai nella foresta,” le disse la vecchia, e tornò a casa senza sapere che il principe l’aveva ascoltata di nascosto.

Così quando scese il buio, il principe montò sulla giumenta per la seconda volta e la condusse per i prati, e il puledro trotterellava dietro la madre. Di nuovo riuscì a resistere fino a mezzanotte; poi lo colse un sonno che di nuovo non avrebbe potuto combattere, e quando si svegliò si ritrovò da solo, come la volta precedente, seduto su un ceppo e con le redini in mano. Lanciò un grido di sgomento e si gettò alla ricerca dei vagabondi. Mentre camminava, si rammentò le parole che la vecchia aveva detto alla puledra e tirò fuori i peli di volpe e se li avvolse intorno alle dita.

”Che c’è fratello mio?” chiese la volpe, che in istante era comparsa accanto a lui.

”La giumenta della vecchia strega e scappata via da me e io non so dove cercarla.”

La volpe rispose: “È con noi e si è trasformata in una grossa volpe e il suo puledro in una piccola, ma colpisci il terreno con la briglia e grida: ‘Vieni qui, o puledra della strega della montagna!’”

Il principe fece così e in un attimo la volpe divenne una giumenta e fu dinnanzi a lui, con il puledrino alle calcagna. Egli montò in sella e ritornò indietro; la vecchia mise il cibo sulla tavola e condusse la puledra nella stalla.

”Saresti dovuta andare dalle volpi, come ti avevo detto.” Disse, colpendo la puledra con un bastone.

”Sono andata tra le volpi,” replicò la puledra, “ma non sono mie amiche e mi hanno tradita.”

”Ebbene, stavolta farai meglio ad andare tra i lupi.” Disse la vecchia, senza sapere che il principe aveva sentito tutto ciò che aveva detto.

La terza notte il principe montò la puledra e cavalcò oltre i prati, con il puledro che trottava dopo di loro. Fece molta fatica a restare sveglio, non ci era abituato, e la mattina era di nuovo sul ceppo, che afferrava le redini. Si alzò in piedi e poi si fermò, perché si era rammentato di ciò che aveva detto la vecchia, e tirò fuori la ciocca del lupo grigio.

”Che c’è, fratello mio?” chiese il lupo appena gli fu davanti.

”La giumenta della vecchia strega e scappata via da me,” rispose il principe, “e non so dove trovarla.”

Ilo lupo rispose: “Oh, è con noi e si è trasformata in una lupa, e il puledro in un lupacchiotto; ma colpisci la terra con le briglie e grida: ‘Torna da me, o puledra della strega della montagna.’”

Il principe fece come gli era stato ordinato, e come il pelo toccò le sue dita, il lupo ritornò giumenta con puledro accanto. E quando l’ebbe montata e condotta a casa, la vecchia era sui gradini a riceverlo; mise il cibo davanti al principe e condusse la giumenta nella stalla.

”Saresti dovuta andare tra i lupi,” disse la vecchia, colpendola con un bastone.

“E così ho fatto,” rispose la giumenta, “ma non sono miei amici e mi hanno tradita.”

La vecchia non rispose e lasciò la stalla, ma il principe era sulla porta ad aspettarla.

Le disse: “Ti ho servito bene e adesso dammi la ricompensa.”

”Manterrò ciò che ho promesso,” rispose lei. “Scegli uno dei dodici cavalli; puoi avere quello che vuoi.”

”Invece dammi quell’animale nell’angolo, mezzo morto di fame.” chiese il principe. “Preferisco lui a tutti quegli splendidi animali.”

”Non puoi voler intendere davvero ciò che hai detto.” rispose la donna.

”Invece sì.” disse il principe, e la vecchia fu obbligata a fare ciò che doveva. Così prese commiato da lei e mise le briglie al collo del cavallo, conducendolo nella foresta, dove lo strofinò finché il suo pelo fu scintillante come l’oro. Allora lo montò e volarono dritto nell’aria fino al palazzo del drago. L’imperatrice lo aveva atteso notte e giorno e uscì furtivamente per incontrarlo; lui la sollevò sulla sella e il cavallo volo via di nuovo.

Poco dopo il drago tornò a casa e, quando scoprì che l’imperatrice era scomparsa, disse al suo cavallo: “Che cosa faremo? Mangeremo e berremo o inseguiremo i fuggitivi?” e il cavallo rispose: “Sia che tu mangi o non mangi, beva o non beva, li insegua o resti a casa, non avrà nessuna importanza, perché tu mai e poi mai li potrai catturare.”

il drago non rispose alle parole del cavallo, ma gli balzò in groppa e si lanciò all’inseguimento dei fuggiaschi. Quando lo videro arrivare, ebbero paura e spronarono il cavallo del principe sempre di più finché disse: “Non abbiate paura; non può accaderci alcun male.” E i loro cuori si calmarono perché si fidavano della sua saggezza.

Ben presto si sentì ansimare dietro il cavallo del drago e gridare: “Oh, fratello mio, non andare così veloce! Cadrò a terra se tento di stare al passo con te.”

E il cavallo del principe rispose: “Perché servi un simile mostro? Prendilo a calci e fallo a pezzi sul terreno, poi vieni e unisciti a noi.”

Il cavallo del drago si chinò e si impennò, e il drago cadde su una roccia che lo fece a pezzi. Allora l’imperatrice montò a cavallo e cavalcò dietro il marito verso il suo regno, sul quale governarono per molti anni.

Storia folcloristica delle Serbia

NdT: l'incipit di questa fiaba ci riporta a L'uccello d'oro dei fratelli Grimm. Anche in questa storia dei Grimm c'è un uccello, dalle piume d'oro, che ruba di notte le mele d'oro del re. Tuttavia la fiaba poi si discosta in quanto tre giovani, l'uno dopo l'altro, (i figli del re o del giardiniere, secondo le varianti) vengono mandati a caccia dell'uccello d'oro. i primi due finiscono male e solo l'intervento del fratello minore li salverà, grazie all'aiuto di una volpe magica. I due ingrati e traditori si liberano del fratello generoso e si spacciano per gli eroi della storia, ma la giustizia verrà ristabilita. Qui potete leggere la favola dei fratelli Grimm./small>

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)