The story of a gazelle

(MP3-32'13'')

Once upon a time there lived a man who wasted all his money, and grew so poor that his only food was a few grains of corn, which he scratched like a fowl from out of a dust-heap.

One day he was scratching as usual among a dust-heap in the street, hoping to find something for breakfast, when his eye fell upon a small silver coin, called an eighth, which he greedily snatched up. 'Now I can have a proper meal,' he thought, and after drinking some water at a well he lay down and slept so long that it was sunrise before he woke again. Then he jumped up and returned to the dust-heap. 'For who knows,' he said to himself, 'whether I may not have some good luck again.'

As he was walking down the road, he saw a man coming towards him, carrying a cage made of twigs. 'Hi! you fellow!' called he, 'what have you got inside there?'

'Gazelles,' replied the man.

'Bring them here, for I should like to see them.'

As he spoke, some men who were standing by began to laugh, saying to the man with the cage: 'You had better take care how you bargain with him, for he has nothing at all except what he picks up from a dust-heap, and if he can't feed himself, will he be able to feed a gazelle?'

But the man with the cage made answer: 'Since I started from my home in the country, fifty people at the least have called me to show them my gazelles, and was there one among them who cared to buy? It is the custom for a trader in merchandise to be summoned hither and thither, and who knows where one may find a buyer?' And he took up his cage and went towards the scratcher of dust-heaps, and the men went with him.

'What do you ask for your gazelles?' said the beggar. 'Will you let me have one for an eighth?'

And the man with the cage took out a gazelle, and held it out, saying, 'Take this one, master!'

And the beggar took it and carried it to the dust-heap, where he scratched carefully till he found a few grains of corn, which he divided with his gazelle. This he did night and morning, till five days went by.

Then, as he slept, the gazelle woke him, saying, 'Master.'

And the man answered, 'How is it that I see a wonder?'

'What wonder?' asked the gazelle.

'Why, that you, a gazelle, should be able to speak, for, from the beginning, my father and mother and all the people that are in the world have never told me of a talking gazelle.'

'Never mind that,' said the gazelle, 'but listen to what I say! First, I took you for my master. Second, you gave for me all you had in the world. I cannot run away from you, but give me, I pray you, leave to go every morning and seek food for myself, and every evening I will come back to you. What you find in the dust-heaps is not enough for both of us.'

'Go, then,' answered the master; and the gazelle went.

When the sun had set, the gazelle came back, and the poor man was very glad, and they lay down and slept side by side.

In the morning it said to him, 'I am going away to feed.'

And the man replied, 'Go, my son,' but he felt very lonely without his gazelle, and set out sooner than usual for the dust-heap where he generally found most corn. And glad he was when the evening came, and he could return home. He lay on the grass chewing tobacco, when the gazelle trotted up.

'Good evening, my master; how have you fared all day? I have been resting in the shade in a place where there is sweet grass when I am hungry, and fresh water when I am thirsty, and a soft breeze to fan me in the heat. It is far away in the forest, and no one knows of it but me, and to-morrow I shall go again.'

So for five days the gazelle set off at daybreak for this cool spot, but on the fifth day it came to a place where the grass was bitter, and it did not like it, and scratched, hoping to tear away the bad blades. But, instead, it saw something lying in the earth, which turned out to be a diamond, very large and bright. 'Oh, ho!' said the gazelle to itself, 'perhaps now I can do something for my master who bought me with all the money he had; but I must be careful or they will say he has stolen it. I had better take it myself to some great rich man, and see what it will do for me.'

Directly the gazelle had come to this conclusion, it picked up the diamond in its mouth, and went on and on and on through the forest, but found no place where a rich man was likely to dwell. For two more days it ran, from dawn to dark, till at last early one morning it caught sight of a large town, which gave it fresh courage.

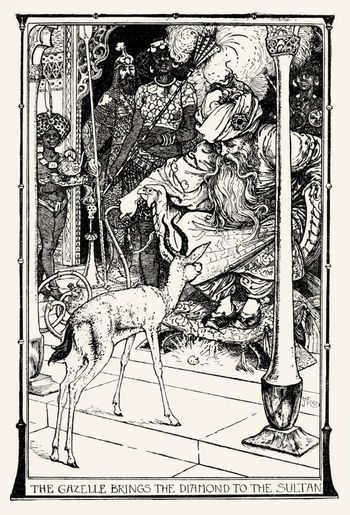

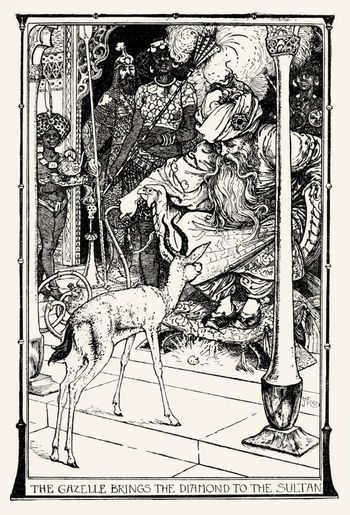

The people were standing about the streets doing their marketing, when the gazelle bounded past, the diamond flashing as it ran. They called after it, but it took no notice till it reached the palace, where the sultan was sitting, enjoying the cool air. And the gazelle galloped up to him, and laid the diamond at his feet.

The sultan looked first at the diamond and next at the gazelle; then he ordered his attendants to bring cushions and a carpet, that the gazelle might rest itself after its long journey. And he likewise ordered milk to be brought, and rice, that it might eat and drink and be refreshed.

And when the gazelle was rested, the sultan said to it: 'Give me the news you have come with.'

And the gazelle answered: 'I am come with this diamond, which is a pledge from my master the Sultan Darai. He has heard you have a daughter, and sends you this small token, and begs you will give her to him to wife.'

And the sultan said: 'I am content. The wife is his wife, the family is his family, the slave is his slave. Let him come to me empty-handed, I am content.'

When the sultan had ended, the gazelle rose, and said: 'Master, farewell; I go back to our town, and in eight days, or it may be in eleven days, we shall arrive as your guests.'

And the sultan answered: 'So let it be.'

All this time the poor man far away had been mourning and weeping for his gazelle, which he thought had run away from him for ever.

And when it came in at the door he rushed to embrace it with such joy that he would not allow it a chance to speak.

'Be still, master, and don't cry,' said the gazelle at last; 'let us sleep now, and in the morning, when I go, follow me.'

With the first ray of dawn they got up and went into the forest, and on the fifth day, as they were resting near a stream, the gazelle gave its master a sound beating, and then bade him stay where he was till it returned. And the gazelle ran off, and about ten o'clock it came near the sultan's palace, where the road was all lined with soldiers who were there to do honour to Sultan Darai. And directly they caught sight of the gazelle in the distance one of the soldiers ran on and said, 'Sultan Darai, is coming: I have seen the gazelle.'

Then the sultan rose up, and called his whole court to follow him, and went out to meet the gazelle, who, bounding up to him, gave him greeting. The sultan answered politely, and inquired where it had left its master, whom it had promised to bring back.

'Alas!' replied the gazelle, 'he is lying in the forest, for on our way here we were met by robbers, who, after beating and robbing him, took away all his clothes. And he is now hiding under a bush, lest a passing stranger might see him.'

The sultan, on hearing what had happened to his future son-in-law, turned his horse and rode to the palace, and bade a groom to harness the best horse in the stable and order a woman slave to bring a bag of clothes, such as a man might want, out of the chest; and he chose out a tunic and a turban and a sash for the waist, and fetched himself a gold-hilted sword, and a dagger and a pair of sandals, and a stick of sweet-smelling wood.

'Now,' said he to the gazelle, 'take these things with the soldiers to the sultan, that he may be able to come.'

And the gazelle answered: 'Can I take those soldiers to go and put my master to shame as he lies there naked? I am enough by myself, my lord.'

'How will you be enough,' asked the sultan, 'to manage this horse and all these clothes?'

'Oh, that is easily done,' replied the gazelle. 'Fasten the horse to my neck and tie the clothes to the back of the horse, and be sure they are fixed firmly, as I shall go faster than he does.'

Everything was carried out as the gazelle had ordered, and when all was ready it said to the sultan: 'Farewell, my lord, I am going.'

'Farewell, gazelle,' answered the sultan; 'when shall we see you again?'

'To-morrow about five,' replied the gazelle, and, giving a tug to the horse's rein, they set off at a gallop.

The sultan watched them till they were out of sight: then he said to his attendants, 'That gazelle comes from gentle hands, from the house of a sultan, and that is what makes it so different from other gazelles.' And in the eyes of the sultan the gazelle became a person of consequence.

Meanwhile the gazelle ran on till it came to the place where its master was seated, and his heart laughed when he saw the gazelle.

And the gazelle said to him, 'Get up, my master, and bathe in the stream!' and when the man had bathed it said again, 'Now rub yourself well with earth, and rub your teeth well with sand to make them bright and shining.' And when this was done it said, 'The sun has gone down behind the hills; it is time for us to go': so it went and brought the clothes from the back of the horse, and the man put them on and was well pleased.

'Master!' said the gazelle when the man was ready, 'be sure that where we are going you keep silence, except for giving greetings and asking for news. Leave all the talking to me. I have provided you with a wife, and have made her presents of clothes and turbans and rare and precious things, so it is needless for you to speak.'

'Very good, I will be silent,' replied the man as he mounted the horse. 'You have given all this; it is you who are the master, and I who am the slave, and I will obey you in all things.' S

o they went their way, and they went and went till the gazelle saw in the distance the palace of the sultan. Then it said, 'Master, that is the house we are going to, and you are not a poor man any longer: even your name is new.'

'What IS my name, eh, my father?' asked the man.

'Sultan Darai,' said the gazelle.

Very soon some soldiers came to meet them, while others ran off to tell the sultan of their approach. And the sultan set off at once, and the viziers and the emirs, and the judges, and the rich men of the city, all followed him.

Directly the gazelle saw them coming, it said to its master: 'Your father-in-law is coming to meet you; that is he in the middle, wearing a mantle of sky-blue. Get off your horse and go to greet him.'

And Sultan Darai leapt from his horse, and so did the other sultan, and they gave their hands to one another and kissed each other, and went together into the palace.

The next morning the gazelle went to the rooms of the sultan, and said to him: 'My lord, we want you to marry us our wife, for the soul of Sultan Darai is eager.'

'The wife is ready, so call the priest,' answered he, and when the ceremony was over a cannon was fired and music was played, and within the palace there was feasting.

'Master,' said the gazelle the following morning, 'I am setting out on a journey, and I shall not be back for seven days, and perhaps not then. But be careful not to leave the house till I come.'

And the master answered, 'I will not leave the house.'

And it went to the sultan of the country and said to him: 'My lord, Sultan Darai has sent me to his town to get the house in order. It will take me seven days, and if I am not back in seven days he will not leave the palace till I return.'

'Very good,' said the sultan.

And it went and it went through the forest and wilderness, till it arrived at a town full of fine houses. At the end of the chief road was a great house, beautiful exceedingly, built of sapphire and turquoise and marbles. 'That,' thought the gazelle, 'is the house for my master, and I will call up my courage and go and look at the people who are in it, if any people there are. For in this town have I as yet seen no people. If I die, I die, and if I live, I live. Here can I think of no plan, so if anything is to kill me, it will kill me.'

Then it knocked twice at the door, and cried 'Open,' but no one answered. And it cried again, and a voice replied:

'Who are you that are crying "Open"?'

And the gazelle said, 'It is I, great mistress, your grandchild.'

'If you are my grandchild,' returned the voice, 'go back whence you came. Don't come and die here, and bring me to my death as well.'

'Open, mistress, I entreat, I have something to say to you.'

'Grandchild,' replied she, 'I fear to put your life in danger, and my own too.'

'Oh, mistress, my life will not be lost, nor yours either; open, I pray you.' So she opened the door.

'What is the news where you come from, my grandson,' asked she.

'Great lady, where I come from it is well, and with you it is well.'

'Ah, my son, here it is not well at all. If you seek a way to die, or if you have not yet seen death, then is to-day the day for you to know what dying is.'

'If I am to know it, I shall know it,' replied the gazelle; 'but tell me, who is the lord of this house?'

And she said: 'Ah, father! in this house is much wealth, and much people, and much food, and many horses. And the lord of it all is an exceeding great and wonderful snake.'

'Oh!' cried the gazelle when he heard this; 'tell me how I can get at the snake to kill him?'

'My son,' returned the old woman, 'do not say words like these; you risk both our lives. He has put me here all by myself, and I have to cook his food. When the great snake is coming there springs up a wind, and blows the dust about, and this goes on till the great snake glides into the courtyard and calls for his dinner, which must always be ready for him in those big pots. He eats till he has had enough, and then drinks a whole tankful of water. After that he goes away. Every second day he comes, when the sun is over the house. And he has seven heads. How then can you be a match for him, my son?'

'Mind your own business, mother,' answered the gazelle, 'and don't mind other people's! Has this snake a sword?'

'He has a sword, and a sharp one too. It cuts like a dash of lightning.'

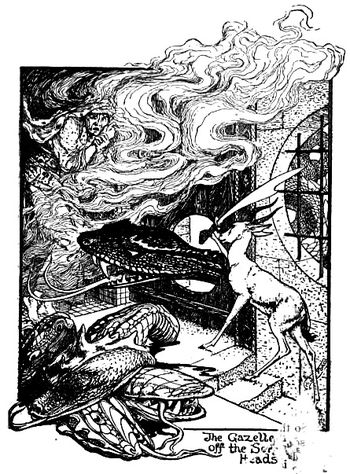

'Give it to me, mother!' said the gazelle, and she unhooked the sword from the wall, as she was bidden. 'You must be quick,' she said, 'for he may be here at any moment. Hark! is not that the wind rising? He has come!'

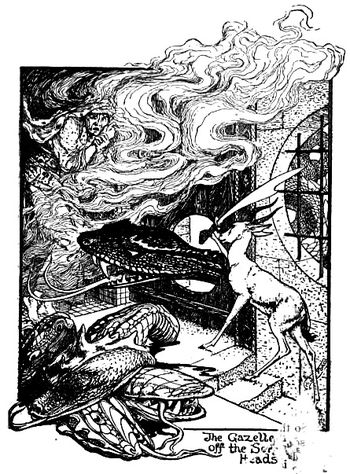

They were silent, but the old woman peeped from behind a curtain, and saw the snake busy at the pots which she had placed ready for him in the courtyard. And after he had done eating and drinking he came to the door:

'You old body!' he cried; 'what smell is that I smell inside that is not the smell of every day?'

'Oh, master!' answered she, 'I am alone, as I always am! But to-day, after many days, I have sprinkled fresh scent all over me, and it is that which you smell. What else could it be, master?'

All this time the gazelle had been standing close to the door, holding the sword in one of its front paws. And as the snake put one of his heads through the hole that he had made so as to get in and out comfortably, it cut it of so clean that the snake really did not feel it. The second blow was not quite so straight, for the snake said to himself, 'Who is that who is trying to scratch me?' and stretched out his third head to see; but no sooner was the neck through the hole than the head went rolling to join the rest.

When six of his heads were gone the snake lashed his tail with such fury that the gazelle and the old woman could not see each other for the dust he made. And the gazelle said to him, 'You have climbed all sorts of trees, but this you can't climb,' and as the seventh head came darting through it went rolling to join the rest.

Then the sword fell rattling on the ground, for the gazelle had fainted.

The old woman shrieked with delight when she saw her enemy was dead, and ran to bring water to the gazelle, and fanned it, and put it where the wind could blow on it, till it grew better and gave a sneeze. And the heart of the old woman was glad, and she gave it more water, till by-and-by the gazelle got up.

'Show me this house,' it said, 'from beginning to end, from top to bottom, from inside to out.'

So she arose and showed the gazelle rooms full of gold and precious things, and other rooms full of slaves. 'They are all yours, goods and slaves,' said she.

But the gazelle answered, 'You must keep them safe till I call my master.'

For two days it lay and rested in the house, and fed on milk and rice, and on the third day it bade the old woman farewell and started back to its master.

And when he heard that the gazelle was at the door he felt like a man who has found the time when all prayers are granted, and he rose and kissed it, saying: 'My father, you have been a long time; you have left sorrow with me. I cannot eat, I cannot drink, I cannot laugh; my heart felt no smile at anything, because of thinking of you.'

And the gazelle answered: 'I am well, and where I come from it is well, and I wish that after four days you would take your wife and go home.' And he said: 'It is for you to speak. Where you go, I will follow.'

'Then I shall go to your father-in-law and tell him this news.'

'Go, my son.'

So the gazelle went to the father-in-law and said: 'I am sent by my master to come and tell you that after four days he will go away with his wife to his own home.'

'Must he really go so quickly? We have not yet sat much together, I and Sultan Darai, nor have we yet talked much together, nor have we yet ridden out together, nor have we eaten together; yet it is fourteen days since he came.'

But the gazelle replied: 'My lord, you cannot help it, for he wishes to go home, and nothing will stop him.'

'Very good,' said the sultan, and he called all the people who were in the town, and commanded that the day his daughter left the palace ladies and guards were to attend her on her way.

And at the end of four days a great company of ladies and slaves and horses went forth to escort the wife of Sultan Darai to her new home. They rode all day, and when the sun sank behind the hills they rested, and ate of the food the gazelle gave them, and lay down to sleep. And they journeyed on for many days, and they all, nobles and slaves, loved the gazelle with a great love—more than they loved the Sultan Darai.

At last one day signs of houses appeared, far, far off. And those who saw cried out, 'Gazelle!'

And it answered, 'Ah, my mistresses, that is the house of Sultan Darai.'

At this news the women rejoiced much, and the slaves rejoiced much, and in the space of two hours they came to the gates, and the gazelle bade them all stay behind, and it went on to the house with Sultan Darai.

When the old woman saw them coming through the courtyard she jumped and shouted for joy, and as the gazelle drew near she seized it in her arms, and kissed it. The gazelle did not like this, and said to her: 'Old woman, leave me alone; the one to be carried is my master, and the one to be kissed is my master.'

And she answered, 'Forgive me, my son. I did not know this was our master,' and she threw open all the doors so that the master might see everything that the rooms and storehouses contained. Sultan Darai looked about him, and at length he said:

'Unfasten those horses that are tied up, and let loose those people that are bound. And let some sweep, and some spread the beds, and some cook, and some draw water, and some come out and receive the mistress.'

And when the sultana and her ladies and her slaves entered the house, and saw the rich stuffs it was hung with, and the beautiful rice that was prepared for them to eat, they cried: 'Ah, you gazelle, we have seen great houses, we have seen people, we have heard of things. But this house, and you, such as you are, we have never seen or heard of.'

After a few days, the ladies said they wished to go home again. The gazelle begged them hard to stay, but finding they would not, it brought many gifts, and gave some to the ladies and some to their slaves. And they all thought the gazelle greater a thousand times than its master, Sultan Darai.

The gazelle and its master remained in the house many weeks, and one day it said to the old woman, 'I came with my master to this place, and I have done many things for my master, good things, and till to-day he has never asked me: "Well, my gazelle, how did you get this house? Who is the owner of it? And this town, were there no people in it?" All good things I have done for the master, and he has not one day done me any good thing. But people say, "If you want to do any one good, don't do him good only, do him evil also, and there will be peace between you." So, mother, I have done: I want to see the favours I have done to my master, that he may do me the like.'

'Good,' replied the old woman, and they went to bed.

In the morning, when light came, the gazelle was sick in its stomach and feverish, and its legs ached. And it said 'Mother!'

And she answered, 'Here, my son?'

And it said, 'Go and tell my master upstairs the gazelle is very ill.'

'Very good, my son; and if he should ask me what is the matter, what am I to say?'

'Tell him all my body aches badly; I have no single part without pain.'

The old woman went upstairs, and she found the mistress and master sitting on a couch of marble spread with soft cushions, and they asked her, 'Well, old woman, what do you want?'

'To tell the master the gazelle is ill,' said she.

'What is the matter?' asked the wife.

'All its body pains; there is no part without pain.'

'Well, what can I do? Make some gruel of red millet, and give to it.'

But his wife stared and said: 'Oh, master, do you tell her to make the gazelle gruel out of red millet, which a horse would not eat? Eh, master, that is not well.'

But he answered, 'Oh, you are mad! Rice is only kept for people.'

'Eh, master, this is not like a gazelle. It is the apple of your eye. If sand got into that, it would trouble you.'

'My wife, your tongue is long,' and he left the room.

The old woman saw she had spoken vainly, and went back weeping to the gazelle. And when the gazelle saw her it said, 'Mother, what is it, and why do you cry? If it be good, give me the answer; and if it be bad, give me the answer.'

But still the old woman would not speak, and the gazelle prayed her to let it know the words of the master. At last she said: 'I went upstairs and found the mistress and the master sitting on a couch, and he asked me what I wanted, and I told him that you, his slave, were ill. And his wife asked what was the matter, and I told her that there was not a part of your body without pain. And the master told me to take some red millet and make you gruel, but the mistress said, 'Eh, master, the gazelle is the apple of your eye; you have no child, this gazelle is like your child; so this gazelle is not one to be done evil to. This is a gazelle in form, but not a gazelle in heart; he is in all things better than a gentleman, be he who he may.'

And he answered her, 'Silly chatterer, your words are many. I know its price; I bought it for an eighth. What loss will it be to me?'

The gazelle kept silence for a few moments. Then it said, 'The elders said, "One that does good like a mother," and I have done him good, and I have got this that the elders said. But go up again to the master, and tell him the gazelle is very ill, and it has not drunk the gruel of red millet.'

So the old woman returned, and found the master and the mistress drinking coffee. And when he heard what the gazelle had said, he cried: 'Hold your peace, old woman, and stay your feet and close your eyes, and stop your ears with wax; and if the gazelle bids you come to me, say your legs are bent, and you cannot walk; and if it begs you to listen, say your ears are stopped with wax; and if it wishes to talk, reply that your tongue has got a hook in it.'

The heart of the old woman wept as she heard such words, because she saw that when the gazelle first came to that town it was ready to sell its life to buy wealth for its master. Then it happened to get both life and wealth, but now it had no honour with its master.

And tears sprung likewise to the eyes of the sultan's wife, and she said, 'I am sorry for you, my husband, that you should deal so wickedly with that gazelle'; but he only answered, 'Old woman, pay no heed to the talk of the mistress: tell it to perish out of the way. I cannot sleep, I cannot eat, I cannot drink, for the worry of that gazelle. Shall a creature that I bought for an eighth trouble me from morning till night? Not so, old woman!'

The old woman went downstairs, and there lay the gazelle, blood flowing from its nostrils. And she took it in her arms and said, 'My son, the good you did is lost; there remains only patience.'

And it said, 'Mother, I shall die, for my soul is full of anger and bitterness. My face is ashamed, that I should have done good to my master, and that he should repay me with evil.' It paused for a moment, and then went on, 'Mother, of the goods that are in this house, what do I eat? I might have every day half a basinful, and would my master be any the poorer? But did not the elders say, "He that does good like a mother!"'

And it said, 'Go and tell my master that the gazelle is nearer death than life.'

So she went, and spoke as the gazelle had bidden her; but he answered, 'I have told you to trouble me no more.'

But his wife's heart was sore, and she said to him: 'Ah, master, what has the gazelle done to you? How has he failed you? The things you do to him are not good, and you will draw on yourself the hatred of the people. For this gazelle is loved by all, by small and great, by women and men. Ah, my husband! I thought you had great wisdom, and you have not even a little!'

But he answered, 'You are mad, my wife.'

The old woman stayed no longer, and went back to the gazelle, followed secretly by the mistress, who called a maidservant and bade her take some milk and rice and cook it for the gazelle.

'Take also this cloth,' she said, 'to cover it with, and this pillow for its head. And if the gazelle wants more, let it ask me, and not its master. And if it will, I will send it in a litter to my father, and he will nurse it till it is well.'

And the maidservant did as her mistress bade her, and said what her mistress had told her to say, but the gazelle made no answer, but turned over on its side and died quietly.

When the news spread abroad, there was much weeping among the people, and Sultan Darai arose in wrath, and cried, 'You weep for that gazelle as if you wept for me! And, after all, what is it but a gazelle, that I bought for an eighth?'

But his wife answered, 'Master, we looked upon that gazelle as we looked upon you. It was the gazelle who came to ask me of my father, it was the gazelle who brought me from my father, and I was given in charge to the gazelle by my father.'

And when the people heard her they lifted up their voices and spoke:

'We never saw you, we saw the gazelle. It was the gazelle who met with trouble here, it was the gazelle who met with rest here. So, then, when such an one departs from this world we weep for ourselves, we do not weep for the gazelle.'

And they said furthermore:

'The gazelle did you much good, and if anyone says he could have done more for you he is a liar! Therefore, to us who have done you no good, what treatment will you give? The gazelle has died from bitterness of soul, and you ordered your slaves to throw it into the well. Ah! leave us alone that we may weep.'

But Sultan Darai would not heed their words, and the dead gazelle was thrown into the well.

When the mistress heard of it, she sent three slaves, mounted on donkeys, with a letter to her father the sultan, and when the sultan had read the letter he bowed his head and wept, like a man who had lost his mother. And he commanded horses to be saddled, and called the governor and the judges and all the rich men, and said:

'Come now with me; let us go and bury it.'

Night and day they travelled, till the sultan came to the well where the gazelle had been thrown. And it was a large well, built round a rock, with room for many people; and the sultan entered, and the judges and the rich men followed him. And when he saw the gazelle lying there he wept afresh, and took it in his arms and carried it away.

When the three slaves went and told their mistress what the sultan had done, and how all the people were weeping, she answered:

'I too have eaten no food, neither have I drunk water, since the day the gazelle died. I have not spoken, and I have not laughed.'

The sultan took the gazelle and buried it, and ordered the people to wear mourning for it, so there was great mourning throughout the city.

Now after the days of mourning were at an end, the wife was sleeping at her husband's side, and in her sleep she dreamed that she was once more in her father's house, and when she woke up it was no dream.

And the man dreamed that he was on the dust-heap, scratching. And when he woke, behold! that also was no dream, but the truth.

Swahili Tales.

Storia di una gazzella

C’era una volta un uomo che sprecò tutto il proprio denaro e divenne così povero che il suo unico cibo erano pochi chicchi di mais che razzolava come un pollo dal mucchio dei rifiuti.

Un giorno come il solito stava razzolando nell’immondizia della strada, sperando di trovare qualcosa per colazione, quando lo sguardo gli cadde su una monetina d’argento, detta ottava, che arraffò avidamente. “Adesso potrò procurarmi un pasto adeguato.” pensò e, dopo aver bevuto un po’ d’acqua alla sorgente, si sdraiò e dormì tanto a lungo che venne l’alba prima che si svegliasse di nuovo. Allora balzò in piedi e tornò presso la spazzatura. “Chi lo sa,” disse tra sé, “che non possa avere di nuovo fortuna.”

Mentre stava camminando lungo la strada, vide un uomo che veniva verso di lui portando una gabbia fatta di rametti. “Ehi, voi!” lo chiamò, “Che cosa avete lì dentro?”

”Gazzelle.” rispose l’uomo.

”Portatele qui, mi piacerebbe vederle.”

Come ebbe parlato, alcuni uomini che stavano lì cominciarono a ridere, dicendo all’uomo con la gabbia: “Faresti meglio a stare attento a metterti d’accordo con lui perché non possiede nulla tranne ciò che raccatta dalla spazzatura; se non è in grado di nutrire se stesso, come potrà nutrire una gazzella?”

Ma l’uomo con la gabbia rispose: “Sin da quando ho lasciato casa mia nel mio paese, almeno cinquanta persone mi hanno chiesto di mostrare loro le gazzelle e ce n’è stato forse uno tra di loro che si è preoccupato di comprarle? È usanza per un mercante essere chiamato qua e là e chi sa dove possa trovare un acquirente?” E lui riprese la sua gabbia e andò verso colui che frugava nell’immondizia, e gli uomini lo seguirono.

”Quanto volete per una gazzella?” disse il mendicante. “Me ne dareste una per un ottavo?”

L’uomo con la gabbia estrasse una gazzella e la tenne fuori, dicendo: “Prendete questa, signore!”

Il mendicante la prese e la portò nella spazzatura, dove frugò attentamente finché trovò alcuni chicchi di grano che divise con la gazzella. Fece così notte e giorno, finché furono trascorsi cinque giorni.

Allora, mentre dormiva, la gazzella lo svegliò, dicendo: “Padrone.”

E l’uomo rispose: “Com’è possibile che io assista a prodigio?”

”Quale prodigio?” chiese la gazzella.

”Ma come, che tu, una gazzella, sia in grado di parlare perché sin dal principio, mio padre e mia madre e tutta la gente che c’è al mondo non mi hanno mai parlato di una gazzella parlante.”

”Non preoccupatevi di ciò,” disse la gazzella, “e piuttosto ascoltate ciò che vi dico! In primo luogo, vi scelgo come padrone. In secondo luogo, mi avete offerto tutto ciò che avevate al mondo. Io non posso scappare da voi ma, vi prego, lasciatemi andare ogni mattina a cercare cibo per me stessa e ogni sera tornerò da voi. Ciò che trovate nella spazzatura non basta per entrambi.”

”Allora vai.” rispose il padrone e la gazzella andò.

Quando il sole fu tramontato, la gazzella tornò e il poveretto ne fu assai contento, e si sdraiarono a dormire a fianco a fianco.

La mattina essa gli disse: “Sto andando in cerca di cibo.”

E l’uomo rispose: “Vai, figlia mia.” Ma si sentì assai solo senza la gazzella e si dedicò più presto del solito alla spazzatura in cui generalmente trovava un po’ di grano. Ed era contento quando scendeva la sera e poteva tornare a casa. Si era sdraiato sull’erba masticando tabacco quando la gazzella arrivò trotterellando.

”Buonasera, padrone; come ve la siete passata tutto il giorno? Io l’ho trascorso riposando all’ombra in un posto in cui c’era erba dolce per quando avevo fame e acqua fresca per quando avevo sete, e una lieve brezza mi rinfrescava nella calura. È lontano nella foresta, nessun altro lo conosce all’infuori di me e domani vi tornerò di nuovo.”

Così per cinque giorni la gazzella si mosse all’alba verso quel luogo fresco, ma il quinto giorno giunse in un luogo in cui l’erba era amara, non le piacque, e grattò la terra, sperando di strappar via le foglie cattive. Invece vide qualcosa nella terra che si rivelò essere un diamante, assai grande e lucente. “Oh, ho!” esclamò la gazzella tra sé, “forse adesso posso fare qualcosa per il mio padrone che mi ha acquistata con tutto il denaro che possedeva; ma devo stare attenta o diranno che l’ha rubato. Farò meglio a portarlo a qualche riccone per vedere che cosa farà per me.”

Appena giunta a questa conclusione, la gazzella prese in bocca il diamante e andò avanti e indietro per la foresta, ma non trovò un luogo in cui a un riccone piacesse abitare. Corse per due giorni, dall’alba al tramonto, finché infine di prima mattina giunse in vista di una grande città che le restituì il coraggio.

La gente era per strada intenta ai propri affari quando la gazzella balzò avanti, il diamante che scintillava mentre correva. La interrogarono su ciò, ma lei fece finta di nulla finché ebbe raggiunto il palazzo in cui si trovava il sultano, che si godeva l’aria fresca. La gazzella corse da lui e lo depose ai suoi piedi.

Il sultano prima guardò il diamante e dopo la gazzella, poi ordinò ai servitori di portare dei cuscini e un tappeto, così che la gazzella potesse riposare dopo il lungo viaggio. Ordinò inoltre che portassero latte e riso così che potesse mangiare, bere e rinfrescarsi.

Quando la gazzella si fu riposata, il sultano le disse: “Raccontami le novità che porti.”

La gazzella rispose: “Sono venuta con questo diamante che è un pegno da parte del mio padroen, il sultano Darai. Ha sentito che avete una figlia e manda questo piccolo tributo, pregandovi di concedergliela in moglie.”

Il sultano disse: “Sono soddisfatto. La moglie è sua, la famiglia è sua, lo schiavo è suo. Che venga da me a mani vuote, sono soddisfatto.”

Quando il sultano ebbe terminato, la gazzella sia alzò e disse. “Addio, signore, torno nella nostra città e in otto giorni, al massimo undici, saremo qui come vostri ospiti.”

Il sultano rispose: “E così sia.”

In tutto questo tempo il pover’uomo lontano si stava affliggendo e stava piangendo per la sua gazzella, perché pensava che se ne fosse andata via da lui per sempre.

Perciò quando essa giunse alla porta, si precipitò ad abbracciarla con una gioia tale che quasi non era in grado di parlare.

”State tranquillo, padrone, e non piangete,” disse la gazzella alla fine; “adesso andiamo a dormire e domattina, quando me ne andrò, seguitemi.”

Ai primi raggi del sole essi si alzarono e andarono nella foresta; il quinto giorno, mentre stavano riposando vicino a un ruscello, la gazzella diede al padrone una sonora battuta e poi gli ordinò di restare lì finché fosse tornata. La gazzella corse via e verso le dieci giunse vicino al palazzo del sultano, nella strada lungo la quale erano schierati i soldati che si trovavano lì per rendere onore al sultano Darai. Come videro la gazzella in lontananza, uno dei soldati corse avanti e disse: “Il sultano Darai,sta arrivando, ho visto la gazzella.”

Allora il sultano si alzò, chiamò a sé l’intera corte perché lo seguisse e andò incontro alla gazzella la quale, balzandogli davanti, gli porse i propri saluti. Il sultano rispose garbatamente e chiese dove avesse lasciato il padrone, che gli aveva promesso di riportare.

La gazzella rispose: “Ahimè, giace nella foresta perché lungo la strada per venire qui abbiamo incontrato i ladri i quali, dopo averlo picchiato e derubato, hanno portato via tutti i suoi vestiti. Adesso si sta nascondendo in un cespuglio, affinché uno straniero di passaggio non possa vederlo.”

Sentendo ciò che era accaduto al futuro genero, il sultano voltò il cavallo e tornò a palazzo, ordinò a uno stalliere di bardare il miglior cavallo delle scuderie e a una serva di tirar fuori dal forziere una borsa di abiti che un uomo avrebbe potuto desiderare; scelse una tunica, un turbante e una fascia come cintura, prese egli stesso una spada dall’elsa dorata, un pugnale, un paio di sandali e un ramoscello di legno dolce aromatico.

Disse alla gazzella: “Adesso prendi questa roba con i soldati, così che egli possa venire.”

La gazzella rispose: “Come posso prendere questi soldati e andare dal mio padrone che giace nudo e si vergogna? Basto io da sola, mio signore.”

Il sultano disse: “Come puoi bastare tu sola a portare il cavallo e tutti questi abiti?”

”Oh, è semplice,” replicò la gazzella. “Attaccate il cavallo al mio collo e legate gli abiti sul dorso del cavallo, assicurandovi che siano ben fissati, in modo che io possa andare più veloce di lui.”

Fu fatta ogni cosa come aveva ordinato la gazzella e , quando tutto fu pronto, disse la sultano: “Addio, mio signore, me ne vado.”

”Addio, gazzella,” rispose il sultano, “quando ti rivedremo di nuovo?”

”Tra cinque giorni.” Rispose la gazzella e, dando uno strattone alle redini del cavallo, si allontanarono al galoppo.

Il sultano li guardò finché li perse di vista, poi disse ai servitori: “Quella gazzella viene da mani garbate, dalla casa di un sultano, ed è ciò che la rende così diversa dalle altre gazzelle.” E agli occhi del sultano la gazzella divenne una persona importante.

Nel frattempo la gazzella corse finché giunse nel posto in cui era seduto il suo padrone, il cui cuore esultò alla vista della gazzella.

La gazzella gli disse: “Animo, padron mio, lavatevi nel ruscello!” E quando l’uomo si fu lavato, disse ancora: “Adesso datevi una bella strigliata e strofinate i denti con la sabbia per renderli luminosi e scintillanti.” E quando ciò fu fatto, disse: “Il sole è tramontato dietro le colline; per noi è tempo di andare.” Così andò a prendere gli abiti sul dorso del cavallo, l’uomo li indossò e ne fu molto soddisfatto.

Quando l’uomo fu pronto, la gazzella disse: “Padrone! Assicuratevi di restare in silenzio nel luogo in cui stiamo andando, eccetto che per salutare e chiedere notizie. Lasciate che sia solo io a parlare. Vi ho procurato una moglie e preparato per lei doni di abiti e turbanti e altre cose rare e preziose, così non è necessario che voi parliate.”

”Benissimo, resterò in silenzio.” rispose l’uomo mentre montava a cavallo. “Hai procurato tutto ciò; sei tu il padrone e io lo schiavo, ti obbedirò in tutto.”

Così ripresero il cammino e andarono, andarono finché la gazzella vide in lontananza il palazzo del sultano. Allora disse. “Padrone, quella è la casa verso cui siamo diretti e voi non sarete un pover’uomo ancora per molto: persino il vostro nome è nuovo.”

”Qual è il mio nome, padre mio?” chiese l’uomo.

”Sultano Darai.” disse la gazzella.

Assai presto vennero loro incontro alcuni soldati mentre altri correvano ad avvertire il sultano del loro approssimarsi. Il sultano venne fuori subito e lo seguirono tutti i visir e gli emiri, e i giudici e i benestanti della città.

Appena la gazzella li vide che venivano, disse al padrone: “Vostro suocero vi sta venendo incontro: è quello nel mezzo, con addosso un mantello blu. Smontate da cavallo e andate a salutarlo.”

Il sultano Darai scese da cavallo e così fece l’altro sultano, si tesero le mani l’un l’altro, si baciarono a vicenda e entrarono insieme nel palazzo.

Il mattino seguente la gazzella andò nella stanza del sultano e gli disse. “Mio signore, vogliamo che voi ci diate in moglie la nostra sposa perché l’animo del sultano Darai è desideroso.”

”La sposa è pronto, chiamate il celebrante.” Rispose, e qua do la cerimonia fu terminata, fu sparato un colpo di cannone e suonata della musica, e all’interno del palazzo si fece festa.

Il mattino seguente la gazzella disse: “Padrone, sto per partire per un viaggio e non sarò di ritorno che fra sette giorni, forse neppure per allora. Badate bene a non lasciare la casa finché non sarò tornata.”

Il padrone rispose: “Non lascerò la casa.”

Andò quindi dal sultano del paese e gli disse. “Mio signore, il sultano Darai mi manda nella sua città a mettere in ordine la casa. Mi occorreranno sette giorni e se non sarò ritornato entro sette giorni, lui non lascerà il palazzo fino al mio rientro.”

”Molto bene.” disse il sultano.

E la gazzella andò attraverso la foresta e terre selvagge finché giunse in una città piena di belle case. Al termine della via principale c’era una grande casa, straordinariamente bella, costruita con zaffiri, turchesi e marmi. “La gazzella pensò: “Questa è la casa per il mio padrone, devo radunare tutto il mio coraggio e andare a vedere chi vi sia dentro, che gente sia. Perché finora in città non ho visto gente. Se muoio, muoio, e se vivo, vivo. Non faccio progetti, così se qualcosa deve uccidermi, mi ucciderà.”

Poi bussò due volte alla porta e gridò: “Aprite.” Ma non rispose nessuno. Gridò di nuovo e una voce rispose:

”Chi sei, tu che hai gridato ‘Aprite’?”

E la gazzella disse: “Sono io, nobile padrona, vostro nipote.”

”Se sei mio nipote,” replicò la voce, “tornatene da dove sei venuto. Non venire a morire qui e a procurare la morte anche a me.”

”Aprite, signora, vi supplico, ho qualcosa da dirvi.”

Lei rispose: “Nipotino, temo di mettere in pericolo la tua vita e anche la mia.”

”Oh, signora, né la mia, né la vostra vita saranno perdute; aprite, ve ne prego.” Così lei aprì la porta.

”Quali novità mi porti da dove vieni, nipote mio?” chiese.

”Nobile signora, da dove io vengo, va tutto bene e va tutto bene anche per voi.”

”Ah, figlio mio, qui non bane niente del tutto. Se cerchi un modo per morire o non hai ancora incontrato la morte, allora oggi è il giorno in cui imparerai che cos’è la morte.”

”Se dovrò imparalo, lo imparerò,” rispose la gazzella, “ma, ditemi, chi è il padrone di casa?”

Lei rispose: “Ah, buon Dio! In questa casa ci sono molta ricchezza e molta gente, molto cibo e molti cavalli. Il padrone di tutto ciò è un serpente eccezionalmente grande e prodigioso.”

Quando la gazzella ebbe udito ciò, esclamò: “Ditemi come posso giungere al serpente e ucciderlo.”

La vecchia replicò: “Figlio mio, non pronunciare simili parole; metti a rischio entrambe le nostre vite. Mi ha lasciata qui sola e devo cucinare il suo cibo. Quando il grande serpente sta arrivando, qui si alza il vento e la polvere vortica ed è così finché il grande serpente striscia in cortile e reclama la cena, che deve essere sempre pronta per lui in quelle grandi pentole. Mangia finché ne ha abbastanza poi beve un intero serbatoio d’acqua. Dopodiché se ne va. Viene ogni due giorni, quando il sole ha oltrepassato la casa. Ha sette teste. Come puoi scontrarti con lui, figlio mio?”

”Badate ai fatti vostri, madre,” rispose la gazzella, “e non preoccupatevi di quelli degli altri. Questo serpente ha una spada?”

”Sì, ce l’ha ed è anche affilata. Taglia come una saetta.”

”Datela a me, madre!” disse la gazzella, e la donna staccò la spada dal muro, come le era stato ordinato. “Devi essere veloce,” disse, “perché potrebbe essere qui a momenti. Ascolta! Non si sta sollevando il vento? È arrivato!”

C’era silenzio, ma la vecchia spiò da dietro una tenda e vide il serpente occupato con le pentole che aveva sistemato pronte per lui nel cortile. Dopo che ebbe mangiato e bevuto, venne alla porta:

”Ehi, tu, vecchia carcassa!” gridò; “che cos’è l’odore che sento dentro e che non è l’odore di tutti i giorni?”

Lei rispose: “O, padrone! Sono sola, sono sempre sola! Ma oggi, dopo molti giorni, mi sono spruzzata addosso un profumo nuovo, e ed è questo che voi sentite. Che altro potrebbe essere, padrone?”

Nel frattempo la gazzella stava vicino alla porta, reggendo la spada con una delle zampe anteriori. Come il serpente mise una delle teste dentro il buco che aveva fatto per entrare e uscire comodamente, la tagliò con tale precisione che il serpente proprio non se ne accorse. Il secondo colpo non fu del tutto dritto perché il serpente si disse: “Chi sta tentando di graffiarmi?” e allungò la terza testa per vedere, ma appena il collo fu passato per il buco, la testa rotolò a raggiungere il resto.

Quando la sesta testa fu andata, il serpente dimenò la coda con tale furia che la gazzella e la vecchia non si vedevano l’una con l’altra per la polvere che sollevava. La gazzella gli disse:” Ti sei arrampicato su ogni tipo di albero, ma qui non puoi arrampicarti.” E appena la settima testa saettò attraverso, finì a rotolare con le altre.

Poi la spade cadde sferragliando per terra perchè la gazzella era svenuta.

La vecchia gridò di gioia quando vide il nemico morto e corse a prendere acqua per la gazzella, e le fece aria e la pose dove il vento soffiava, finché si riprese e fece uno starnuto. Il cuore della vecchia fu colmo di gioia e le diede altra acqua, finché in breve la gazzella si sollevò.

”Mostrami questa casa,” disse, “dal principio alla fine, da cima a fondo, dall’interno all’esterno.”

Così la vecchia si alzò e mostrò alla gazzella stanze colme d’oro e di oggetti preziosi, e altre stanze piene di schiavi. “È tutto tuo, beni e schiavi.” disse.

La gazzella però rispose: “Devi custodire tutto finché chiamerò il mio padrone.”

Rimase in casa due giorni a riposare, si nutrì di riso e di latte, e il terzo giorno disse addio alla vecchia e ritornò dal padrone.

Quando lui udì che la gazzella era alla porta, si sentì come un uomo le cui preghiere fossero state esaudite, si alzò e la baciò, dicendo: “Madre mia, quanto tempo è passato; mi hai lasciato la sofferenza: Non potevo mangiare, bere ridere, il mio cuore non gioiva di nulla a causa tua.”

La gazzella rispose: “Sto bene e da dove vengo, va tutto bene; desidero che tra quattro giorni prendiate la vostra sposa e andiate a casa.”

E l’uomo rispose. “Come tu dici. Dove andrai, ti seguirò.”

”Allora andrò da vostro suocero e gli racconterò le novità.”

”Andiamo, figlia mia.”

Così la gazzella andò dal suocero e disse. “Mi manda il mio padrone per dirvi che tra quattro giorni condurrà sua moglie nella nuova casa.”

”Veramente farà così in fretta? Non ci siamo ancora seduti insieme, io e il sultano Darai, non abbiamo ancora parlato abbastanza né cavalcato insieme, non abbiamo mangiato insieme; sono già quattordici giorni che se n’è andato.”

La gazzella rispose. “Mio signore, non potete farci nulla perché desidera andare a casa e niente lo fermerà.”

”Benissimo.” disse il sultano e chiamò tutta la gente in città e ordinò che il giorno in cui sua figlia avesse lasciato il palazzo, dame e guardie l’avrebbero scortata lungo la strada.

Al termine dei quattro giorni una gran quantità di dame, schiavi e cavalli uscì a scortare la moglie del sultano Darai verso la sua nuova casa. Cavalcarono tutto il giorno e quando il sole calò dietro le colline, riposarono e mangiarono il cibo che la gazzella diede loro, poi si sdraiarono a dormire. Viaggiarono per molti giorni e tutti, nobili e schiavi, provavano un grande affetto per la gazzella, più che per il sultano Darai.

Infine un giorno in lontananza si videro delle case e tutti coloro che le videro, gridarono: “Gazzella!”

Essa rispose: “Ah, mia signora, quella è la dimora del sultano Darai.”

A questa notizia le donne gioirono molto, così come gli schiavi, e nello spazio di due ore raggiunsero i cancelli; la gazzella ordinò loro di restare tutti lì dietro e andò a casa con il sultano Darai.

Quando la vecchia li vide venire attraverso il cortile, saltò e gridò di gioia, e come la gazzella fu vicina, la abbracciò e la baciò. Alla gazzella tutto ciò non piacque e le disse. “Vecchia, lasciami andare, l’unico che deve essere accolto e baciato è il mio padrone.”

La vecchia rispose. “Perdonami, figlia mia. Non sapevo che lui fosse il tuo padrone.” e aprì tutte le porte così che il padrone potesse vedere ogni cosa che le stanze e i magazzini contenevano. Il sultano Darai si guardò attorno e alla fine disse:

”Sciogliete quei cavalla legati, liberate quella gente che è incatenata. Che qualcuno spazzi e rifaccia i letti, e cucini e attinga acqua, e qualcuno vada a ricevere la padrona.”

Quando la sultana entrò in casa con le dame e con gli schiavi e vide le ricche stoffe appese e il magnifico riso che era stato cucinato perché lo mangiassero, esclamò: “Ah, gazzella, abbiamo visto case grandi e persone, abbiamo udito cose, ma di questa casa e di te, così come sei, non abbiamo mai visto o sentito.”

Dopo pochi giorni le dame dissero che desideravano tornare di nuovo a casa. La gazzella le pregò con ostinazione, ma rendendosi conto che non sarebbero rimaste, portò parecchi doni e ne diede un po’ alle dame e un poi agli schiavi. E tutti pensarono che la gazzella fosse mille volte più nobile del suo padrone, il sultano Darai.

La gazzella e il suo padrone rimasero nella casa per molte settimane e un giorno essa disse alla vecchia: “Sono venuta con il mio padrone in questo posto e ho fatto molte cose per lui, buone cose, e fino a oggi non mi ha mai chiesto: ‘Ebbene, mia gazzella, come ti sei procurata questa casa? Chi ne è il proprietario? E questa città, non ha una popolazione?’. Tutte le cose buone le ho fatte per il mio padrone e lui non ha fatto una sola cosa buona per me. La gente dice: ‘Se vuoi che faccia qualcosa di buono, non dargli solo cose buone, ma dagli anche qualcosa di male, e ci sarà la pace tra di voi.’ Così farò, madre: voglio vedere la benevolenza che ho avuto verso il mio padrone, che egli faccia altrettanto con me.”

”Bene.” rispose la vecchia, e andarono a dormire.

La mattina, quando si fece giorno, la gazzella aveva mal di stomaco, era febbricitante e le dolevano le zampe. Così disse: “Madre!”

E lei rispose: “Sì, figlia mia?”

La gazzella disse: “Andate su dal mio padrone e ditegli che la gazzella sta molto male.”

”Benissimo, figlia mia; e se me ne chiede il motivo, che cosa gli devo dire?”

”Digli che ho tutto il corpo dolorante, non una sola parte che non mi faccia male.”

La vecchia salì al piano superiore e trovò il padrone e la padrona seduti su un divano di marmo cosparso di soffici cuscini, e essi le chiesero. “ebbene, vecchia, che cosa vuoi?”

”Dire al padrone che la gazzella è malata.” rispose.

”Che succede?” chiese la moglie.

”Le duole tutto il corpo; non c’è una parte che non le faccia male.”

”Beh, che ci posso fare? Prendi un po’ di pappa di grano rosso e dagliela.”

La moglie si rizzò e disse: “Oh, mio signore, le dici di dare alla gazzella la pappa di grano rosso che nemmeno un cavallo mangerebbe? Eh,no, mio signore, non va bene.”

Lui rispose: “Sei pazza! Il riso è solo per le persone.”

”Mio signore, questa non è solo una gazzella. È la luce dei tuoi occhi. Se vi dovesse finire della sabbia, saresti nei guai.”

”Moglie mia, la tua lingua è troppo lunga.” rispose, e lasciò la stanza.

La vecchia vide che aveva parlato invano, e tornò in lacrime dalla gazzella. Quando la gazzella la vide, disse: “Madre, che c’è, perché piangi? Se ci sono buone nuove, dammi la risposta; se sono cattive, dammi la risposta.”

Tuttavia la vecchia non avrebbe volute parlare e la gazzella la pregò di farle sapere le parole del padrone. Alla fine la vecchia disse. “Sono salita al piano superiore e ho trovato la padrona e il padrone seduti su un divano, lui mi ha chiesto che cosa volessi e io gli ho detto che tu, la sua schiava, sei malata. Sua moglie ha chiesto che cosa succedesse e io le ho risposto che non c’era una parte del corpo che non ti dolesse. Il padrone mi ha detto di prendere un po’ di grano rosso e dartene la farina, ma la padrona ha detto: ‘Mio signore, la gazzella è la luce dei tuoi occhi; non hai figli e questa gazzella è come un figlio per te; così questa gazzella non è creatura alla quale far del male. È una gazzella nell’aspetto, ma non nel cuore; in tutto è meglio di una gentildonna, e potrebbe esserlo.’

E lui le ha risposto: ‘Sciocca chiacchierona, hai detto troppo. Conosco il suo prezzo, l’ho pagata un pezzo da otto. Che perdita sarebbe mai per me?’

La gazzella rimase per un po’ in silenzio, poi disse. “I saggi dicono: ‘Far del bene a qualcuno come una madre’ e io gli ho fatto del bene, ho fatto ciò che hanno detto i saggi. Torna di nuovo su dal padrone e digli che la gazzella è molto malata e non ha preso la pappa di grano rosso.”

Così la vecchia ritorno e trovò il padrone e la padrona che bevevano caffè. E quando egli udì ciò che aveva detto la gazzella, gridò: “Stai calma, vecchia, resta in piedi, chiudi gli occhi, tappati le orecchie con la cera; se la gazzella ti dice di venire da me, dille che le tue gambe sono curve e non puoi camminare; se ti prega di ascoltare, dille che hai le orecchie tappate con la cera; se desidera parlare, rispondi che la tua lingua è attorcigliata.”

Il cuore della vecchia pianse nel sentire quelle parole perché aveva visto che, quando la gazzella era venuta in città la prima volta, era pronta a dare la vita per conquistare la ricchezza per il suo padrone. Poi era avvenuto che gli aveva procurato sia vita che ricchezza, ma ora non c’era onore nel suo padrone.

Una lacrima spuntò anche dagli occhi della moglie del sultano, e lei disse. “Mi dispiace per te, marito mio, che tratti così perfidamente quella gazzella”, ma lui rispose solo: “Vecchia, non dar retta alle chiacchiere della padrona: dille di andare a morire in strada. Io non posso dormire, mangiare e bere al pensiero di quella gazzella. Può angustiarmi dal mattino alla sera una creatura che ho comprato per una moneta da otto? Non di certo, vecchia!”

La vecchia scese di sotto e lì giaceva la gazzella, con il sangue che le usciva dalle narici. La prese tra le braccia e disse. “Figlia mia, il bene che hai fatto è perduto; non ti resta che la pazienza.”

E la gazzella disse: “Madre, io morirò perché il mio animo è pieno di collera e di amarezza. Il mio volto prova vergogna per il fatto che io abbia fatto del bene al mio padrone e e che lui mi abbia ripagata con il male.” Si fermò un momento e poi proseguì: “Madre, che cosa ho mangiato dei beni contenuti in questa casa? Avrei potuto averne ogni giorno mezzo catino e ciò avrebbe reso più povero il mio padrone? Ma i saggi non dicono ‘Colui che ha fatto del bene come una madre!’”

E disse: “Vai dal mio padrone e digli che la gazzella è più vicina alla morte che alla vita.”

Così andò e disse ciò che la gazzella le aveva ordinate, ma lui rispose. “Ti ho detto di non angustiarmi più.”

Il cuore di sua moglie era dolente e gli disse. “Ah, mio signore, che cosa ti ha fatto la gazzella? In che modo ha mancato verso di te? Ciò che le fai non è bene e ti attirerai l’odio del popolo perché questa gazzella è amata da tutti, piccoli e grandi, donne e uomini. Ah, marito mio! Io pensavo fossi molto saggio, ma non lo sei neanche un po’!”

E lui rispose: “Moglie mia, sei pazza.”

La vecchia non si trattenne più a lungo e tornò dalla gazzella, seguita di nascosto dalla padrona che chiamò una domestica e le ordinò di prendere un po’ di latte e di riso e di cucinarli per la gazzella.

”Prendi anche questo mantello,” disse, “ e coprila, e questo cuscino per la sua testa. Se la gazzella vuole altro, chiedilo a me e non al padrone. Se lei lo desidera, manderò a mio padre una lettera e lui la curerà fino a che starà bene.”

La domestica fece ciò che le aveva ordinate la padrona e disse ciò che aveva detto di dire, ma la gazzella non rispose, volse altrove la testa e morì silenziosamente.

Quando si sparse la notizia, la gente pianse molto e il sultano Darai montò in collera e gridò: ” Piangete per una gazzella come se piangeste per me! Dopotutto che cos’era se non una gazzella che ho comprato per una moneta da otto?”

La moglie rispose: “Mio signore, abbiamo considerato quella gazzella come abbiamo considerato te. Era la gazzella che è venuta a chiedere la mia mano a mio padre, che mi ha condotta via da mio padre e io sono stata concessa in cambio alla gazzella da mio padre.”

E quando il popolo la sentì, alzò la voce e disse:

”Non abbiamo mai visto te, abbiamo visto la gazzella. È stata la gazzella che ha incontrato difficoltà qui, è stata la gazzella che ha trovato riposo qui. Così, quando una simile creatura lascia questo mondo, piangiamo per noi stessi e non per la gazzella.”

E dissero inoltre:

”La gazzella ti ha fatto del bene e chiunque dica il contrario è un bugiardo! Perciò a noi che non ti abbiamo fatto del bene, che trattamento riserverai? La gazzella è morta di amarezza e tu hai ordinato ai tuoi schiavi di gettarla nel pozzo. Ah! Lasciaci soli, così che possiamo piangere.”

Il sultano Darai non volle badare alle loro parole e la gazzella morta fu gettata nel pozzo..

Quando la padrona lo sentì, mandò tre schiavi a dorso d’asino con una lettera per il sultano suo padre, e quando il sultano ebbe eletto la lettera, chinò la testa e pianse, come un uomo che abbia perso la madre. Ordinò che fossero sellati i cavalli e chiamò il sovrintendente, i giudici e tutti i benestanti e disse:

”Adesso venite con me; andiamo a seppellirla.”

Viaggiarono giorno e note finché il costruito intorno a una roccia, con stanze per molte persone; il sultano entrò e i giudici e i benestanti lo seguirono. Quando videro la gazzella che giaceva lì, piansero di nuovo e la presero tra le braccia e la portarono via.

Quando i tre schiavi andarono a dire alla padrona ciò che aveva fatto il sultano, e come tutto il popolo stesse piangendo, lei rispose:

”Anche io non ho mangiato cibo né bevuto acqua dal giorno in cui è morta la gazzella. Non ho parlato e non ho riso.”

Il sultano prese la gazzella e la seppellì, poi ordinò al popolo di indossare abiti da lutto per lei, così che vi fosse grande cordoglio in città.

Dopo che furono terminate I giorni di lutto, la moglie stava dormendo a fianco del marito e nel sonno sognò di essere ancora una volta a casa di suo padre; quando si svegliò, non era un sogno.

L’uomo sognò di essere nella spazzatura a frugare. Quando si svegliò, guarda un po’! non era un sogno, ma la realtà.

Favola Swahili

NdT: L'impianto di questa favola Swahili ci fa pensare a Il gatto con gli stivali : un animale dotato di particolari poteri porta il benessere e una sposa al suo padrone. Solo che nelle varie versioni, il giovane è riconoscente al gatto che ha fatto di lui un uomo ricco e felice e lo tratta con ogni riguardo, a differenza di cio che fa qui il sultano con la povera gazzella.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)