The history of Dwarf Long Nose

(MP3-45'19'')

It is a great mistake to think that fairies, witches, magicians, and such people lived only in Eastern countries and in such times as those of the Caliph Haroun Al-Raschid. Fairies and their like belong to every country and every age, and no doubt we should see plenty of them now—if we only knew how.

In a large town in Germany there lived, some couple of hundred years ago, a cobbler and his wife. They were poor and hard-working. The man sat all day in a little stall at the street corner and mended any shoes that were brought him. His wife sold the fruit and vegetables they grew in their garden in the Market Place, and as she was always neat and clean and her goods were temptingly spread out she had plenty of customers.

The couple had one boy called Jem. A handsome, pleasant-faced boy of twelve, and tall for his age. He used to sit by his mother in the market and would carry home what people bought from her, for which they often gave him a pretty flower, or a slice of cake, or even some small coin.

One day Jem and his mother sat as usual in the Market Place with plenty of nice herbs and vegetables spread out on the board, and in some smaller baskets early pears, apples, and apricots. Jem cried his wares at the top of his voice:

‘This way, gentlemen! See these lovely cabbages and these fresh herbs! Early apples, ladies; early pears and apricots, and all cheap. Come, buy, buy!’

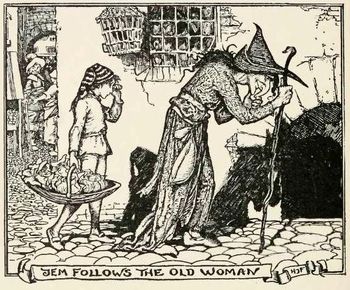

As he cried an old woman came across the Market Place. She looked very torn and ragged, and had a small sharp face, all wrinkled, with red eyes, and a thin hooked nose which nearly met her chin. She leant on a tall stick and limped and shuffled and stumbled along as if she were going to fall on her nose at any moment.

In this fashion she came along till she got to the stall where Jem and his mother were, and there she stopped.

‘Are you Hannah the herb seller?’ she asked in a croaky voice as her head shook to and fro.

‘Yes, I am,’ was the answer. ‘Can I serve you?’

‘We’ll see; we’ll see! Let me look at those herbs. I wonder if you’ve got what I want,’ said the old woman as she thrust a pair of hideous brown hands into the herb basket, and began turning over all the neatly packed herbs with her skinny fingers, often holding them up to her nose and sniffing at them.

The cobbler’s wife felt much disgusted at seeing her wares treated like this, but she dared not speak. When the old hag had turned over the whole basket she muttered, ‘Bad stuff, bad stuff; much better fifty years ago—all bad.’

This made Jem very angry ‘You are a very rude old woman,’ he cried out. ‘First you mess all our nice herbs about with your horrid brown fingers and sniff at them with your long nose till no one else will care to buy them, and then you say it’s all bad stuff, though the duke’s cook himself buys all his herbs from us.’

The old woman looked sharply at the saucy boy, laughed unpleasantly, and said:

‘So you don’t like my long nose, sonny? Well, you shall have one yourself, right down to your chin.’

As she spoke she shuffled towards the hamper of cabbages, took up one after another, squeezed them hard, and threw them back, muttering again, ‘Bad stuff, bad stuff.’

‘Don’t waggle your head in that horrid way,’ begged Jem anxiously. ‘Your neck is as thin as a cabbage-stalk, and it might easily break and your head fall into the basket, and then who would buy anything?’

‘Don’t you like thin necks?’ laughed the old woman. ‘Then you sha’n’t have any, but a head stuck close between your shoulders so that it may be quite sure not to fall off.’

‘Don’t talk such nonsense to the child,’ said the mother at last.

‘If you wish to buy, please make haste, as you are keeping other customers away.’

‘Very well, I will do as you ask,’ said the old woman, with an angry look. ‘I will buy these six cabbages, but, as you see, I can only walk with my stick and can carry nothing. Let your boy carry them home for me and I’ll pay him for his trouble.’

The little fellow didn’t like this, and began to cry, for he was afraid of the old woman, but his mother ordered him to go, for she thought it wrong not to help such a weakly old creature; so, still crying, he gathered the cabbages into a basket and followed the old woman across the Market Place.

It took her more than half an hour to get to a distant part of the little town, but at last she stopped in front of a small tumble-down house. She drew a rusty old hook from her pocket and stuck it into a little hole in the door, which suddenly flew open. How surprised Jem was when they went in! The house was splendidly furnished, the walls and ceiling of marble, the furniture of ebony inlaid with gold and precious stones, the floor of such smooth slippery glass that the little fellow tumbled down more than once.

The old woman took out a silver whistle and blew it till the sound rang through the house. Immediately a lot of guinea pigs came running down the stairs, but Jem thought it rather odd that they all walked on their hind legs, wore nutshells for shoes, and men’s clothes, whilst even their hats were put on in the newest fashion.

‘Where are my slippers, lazy crew?’ cried the old woman, and hit about with her stick. ‘How long am I to stand waiting here?’

They rushed upstairs again and returned with a pair of cocoa nuts lined with leather, which she put on her feet. Now all limping and shuffling was at an end. She threw away her stick and walked briskly across the glass floor, drawing little Jem after her. At last she paused in a room which looked almost like a kitchen, it was so full of pots and pans, but the tables were of mahogany and the sofas and chairs covered with the richest stuffs.

‘Sit down,’ said the old woman pleasantly, and she pushed Jem into a corner of a sofa and put a table close in front of him. ‘Sit down, you’ve had a long walk and a heavy load to carry, and I must give you something for your trouble. Wait a bit, and I’ll give you some nice soup, which you’ll remember as long as you live.’

So saying, she whistled again. First came in guinea pigs in men’s clothing. They had tied on large kitchen aprons, and in their belts were stuck carving knives and sauce ladles and such things. After them hopped in a number of squirrels. They too walked on their hind legs, wore full Turkish trousers, and little green velvet caps on their heads. They seemed to be the scullions, for they clambered up the walls and brought down pots and pans, eggs, flour, butter, and herbs, which they carried to the stove. Here the old woman was bustling about, and Jem could see that she was cooking something very special for him. At last the broth began to bubble and boil, and she drew off the saucepan and poured its contents into a silver bowl, which she set before Jem.

‘There, my boy,’ said she, ‘eat this soup and then you’ll have everything which pleased you so much about me. And you shall be a clever cook too, but the real herb—no, the REAL herb you’ll never find. Why had your mother not got it in her basket?’

The child could not think what she was talking about, but he quite understood the soup, which tasted most delicious. His mother had often given him nice things, but nothing had ever seemed so good as this. The smell of the herbs and spices rose from the bowl, and the soup tasted both sweet and sharp at the same time, and was very strong. As he was finishing it the guinea pigs lit some Arabian incense, which gradually filled the room with clouds of blue vapour. They grew thicker and thicker and the scent nearly overpowered the boy. He reminded himself that he must get back to his mother, but whenever he tried to rouse himself to go he sank back again drowsily, and at last he fell sound asleep in the corner of the sofa.

Strange dreams came to him. He thought the old woman took off all his clothes and wrapped him up in a squirrel skin, and that he went about with the other squirrels and guinea pigs, who were all very pleasant and well mannered, and waited on the old woman.

First he learned to clean her cocoa-nut shoes with oil and to rub them up. Then he learnt to catch the little sun moths and rub them through the finest sieves, and the flour from them he made into soft bread for the toothless old woman.

In this way he passed from one kind of service to another, spending a year in each, till in the fourth year he was promoted to the kitchen. Here he worked his way up from under-scullion to head-pastrycook, and reached the greatest perfection. He could make all the most difficult dishes, and two hundred different kinds of patties, soup flavoured with every sort of herb—he had learnt it all, and learnt it well and quickly.

When he had lived seven years with the old woman she ordered him one day, as she was going out, to kill and pluck a chicken, stuff it with herbs, and have it very nicely roasted by the time she got back. He did this quite according to rule. He wrung the chicken’s neck, plunged it into boiling water, carefully plucked out all the feathers, and rubbed the skin nice and smooth. Then he went to fetch the herbs to stuff it with. In the store-room he noticed a half-opened cupboard which he did not remember having seen before. He peeped in and saw a lot of baskets from which came a strong and pleasant smell. He opened one and found a very uncommon herb in it. The stems and leaves were a bluish green, and above them was a little flower of a deep bright red, edged with yellow. He gazed at the flower, smelt it, and found it gave the same strong strange perfume which came from the soup the old woman had made him. But the smell was so sharp that he began to sneeze again and again, and at last—he woke up!

There he lay on the old woman’s sofa and stared about him in surprise. ‘Well, what odd dreams one does have to be sure!’ he said to himself. ‘Why, I could have sworn I had been a squirrel, a companion of guinea pigs and such creatures, and had become a great cook, too. How mother will laugh when I tell her! But won’t she scold me, though, for sleeping away here in a strange house, instead of helping her at market!’

He jumped up and prepared to go: all his limbs still seemed quite stiff with his long sleep, especially his neck, for he could not move his head easily, and he laughed at his own stupidity at being still so drowsy that he kept knocking his nose against the wall or cupboards. The squirrels and guinea pigs ran whimpering after him, as though they would like to go too, and he begged them to come when he reached the door, but they all turned and ran quickly back into the house again.

The part of the town was out of the way, and Jem did not know the many narrow streets in it and was puzzled by their windings and by the crowd of people, who seemed excited about some show. From what he heard, he fancied they were going to see a dwarf, for he heard them call out: ‘Just look at the ugly dwarf!’ ‘What a long nose he has, and see how his head is stuck in between his shoulders, and only look at his ugly brown hands!’ If he had not been in such a hurry to get back to his mother, he would have gone too, for he loved shows with giants and dwarfs and the like.

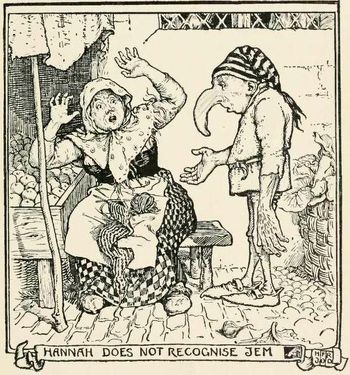

He was quite puzzled when he reached the market-place. There sat his mother, with a good deal of fruit still in her baskets, so he felt he could not have slept so very long, but it struck him that she was sad, for she did not call to the passers-by, but sat with her head resting on her hand, and as he came nearer he thought she looked paler than usual.

He hesitated what to do, but at last he slipped behind her, laid a hand on her arm, and said: ‘Mammy, what’s the matter? Are you angry with me?’

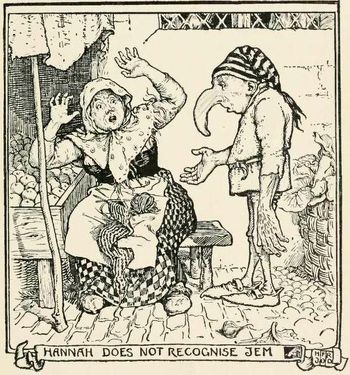

She turned round quickly and jumped up with a cry of horror.

‘What do you want, you hideous dwarf?’ she cried; ‘get away; I can’t bear such tricks.’

‘But, mother dear, what’s the matter with you?’ repeated Jem, quite frightened. ‘You can’t be well. Why do you want to drive your son away?’

‘I have said already, get away,’ replied Hannah, quite angrily. ‘You won’t get anything out of me by your games, you monstrosity.’

‘Oh dear, oh dear! she must be wandering in her mind,’ murmured the lad to himself. ‘How can I manage to get her home? Dearest mother, do look at me close. Can’t you see I am your own son Jem?’

‘Well, did you ever hear such impudence?’ asked Hannah, turning to a neighbour. ‘Just see that frightful dwarf—would you believe that he wants me to think he is my son Jem?’

Then all the market women came round and talked all together and scolded as hard as they could, and said what a shame it was to make game of Mrs. Hannah, who had never got over the loss of her beautiful boy, who had been stolen from her seven years ago, and they threatened to fall upon Jem and scratch him well if he did not go away at once.

Poor Jem did not know what to make of it all. He was sure he had gone to market with his mother only that morning, had helped to set out the stall, had gone to the old woman’s house, where he had some soup and a little nap, and now, when he came back, they were all talking of seven years. And they called him a horrid dwarf! Why, what had happened to him? When he found that his mother would really have nothing to do with him he turned away with tears in his eyes, and went sadly down the street towards his father’s stall.

‘Now I’ll see whether he will know me,’ thought he. ‘I’ll stand by the door and talk to him.’

When he got to the stall he stood in the doorway and looked in. The cobbler was so busy at work that he did not see him for some time, but, happening to look up, he caught sight of his visitor, and letting shoes, thread, and everything fall to the ground, he cried with horror: ‘Good heavens! what is that?’

‘Good evening, master,’ said the boy, as he stepped in. ‘How do you do?’

‘Very ill, little sir,’ replied the father, to Jem’s surprise, for he did not seem to know him. ‘Business does not go well. I am all alone, and am getting old, and a workman is costly.’

‘But haven’t you a son who could learn your trade by degrees?’ asked Jem.

‘I had one: he was called Jem, and would have been a tall sturdy lad of twenty by this time, and able to help me well. Why, when he was only twelve he was quite sharp and quick, and had learnt many little things, and a good-looking boy too, and pleasant, so that customers were taken by him. Well, well! so goes the world!’

‘But where is your son?’ asked Jem, with a trembling voice.

‘Heaven only knows!’ replied the man; ‘seven years ago he was stolen from the market-place, and we have heard no more of him.’

‘SEVEN YEARS AGO!’ cried Jem, with horror.

‘Yes, indeed, seven years ago, though it seems but yesterday that my wife came back howling and crying, and saying the child had not come back all day. I always thought and said that something of the kind would happen. Jem was a beautiful boy, and everyone made much of him, and my wife was so proud of him, and liked him to carry the vegetables and things to grand folks’ houses, where he was petted and made much of. But I used to say, “Take care—the town is large, there are plenty of bad people in it—keep a sharp eye on Jem.” And so it happened; for one day an old woman came and bought a lot of things—more than she could carry; so my wife, being a kindly soul, lent her the boy, and—we have never seen him since.’

‘And that was seven years ago, you say?’

‘Yes, seven years: we had him cried—we went from house to house. Many knew the pretty boy, and were fond of him, but it was all in vain. No one seemed to know the old woman who bought the vegetables either; only one old woman, who is ninety years old, said it might have been the fairy Herbaline, who came into the town once in every fifty years to buy things.’

As his father spoke, things grew clearer to Jem’s mind, and he saw now that he had not been dreaming, but had really served the old woman seven years in the shape of a squirrel. As he thought it over rage filled his heart. Seven years of his youth had been stolen from him, and what had he got in return? To learn to rub up cocoa nuts, and to polish glass floors, and to be taught cooking by guinea pigs! He stood there thinking, till at last his father asked him:

‘Is there anything I can do for you, young gentleman? Shall I make you a pair of slippers, or perhaps’ with a smile—‘a case for your nose?’

‘What have you to do with my nose?’ asked Jem. ‘And why should I want a case for it?’

‘Well, everyone to his taste,’ replied the cobbler; ‘but I must say if I had such a nose I would have a nice red leather cover made for it. Here is a nice piece; and think what a protection it would be to you. As it is, you must be constantly knocking up against things.’

The lad was dumb with fright. He felt his nose. It was thick, and quite two hands long. So, then, the old woman had changed his shape, and that was why his own mother did not know him, and called him a horrid dwarf!

‘Master,’ said he, ‘have you got a glass that I could see myself in?’

‘Young gentleman,’ was the answer, ‘your appearance is hardly one to be vain of, and there is no need to waste your time looking in a glass. Besides, I have none here, and if you must have one you had better ask Urban the barber, who lives over the way, to lend you his. Good morning.’

So saying, he gently pushed Jem into the street, shut the door, and went back to his work.

Jem stepped across to the barber, whom he had known in old days.

‘Good morning, Urban,’ said he; ‘may I look at myself in your glass for a moment?’

‘With pleasure,’ said the barber, laughing, and all the people in his shop fell to laughing also. ‘You are a pretty youth, with your swan-like neck and white hands and small nose. No wonder you are rather vain; but look as long as you like at yourself.’

So spoke the barber, and a titter ran round the room. Meantime Jem had stepped up to the mirror, and stood gazing sadly at his reflection. Tears came to his eyes.

‘No wonder you did not know your child again, dear mother,’ thought he; ‘he wasn’t like this when you were so proud of his looks.’

His eyes had grown quite small, like pigs’ eyes, his nose was huge and hung down over his mouth and chin, his throat seemed to have disappeared altogether, and his head was fixed stiffly between his shoulders. He was no taller than he had been seven years ago, when he was not much more than twelve years old, but he made up in breadth, and his back and chest had grown into lumps like two great sacks. His legs were small and spindly, but his arms were as large as those of a well-grown man, with large brown hands, and long skinny fingers.

Then he remembered the morning when he had first seen the old woman, and her threats to him, and without saying a word he left the barber’s shop.

He determined to go again to his mother, and found her still in the market-place. He begged her to listen quietly to him, and he reminded her of the day when he went away with the old woman, and of many things in his childhood, and told her how the fairy had bewitched him, and he had served her seven years. Hannah did not know what to think—the story was so strange; and it seemed impossible to think her pretty boy and this hideous dwarf were the same. At last she decided to go and talk to her husband about it. She gathered up her baskets, told Jem to follow her, and went straight to the cobbler’s stall.

‘Look here,’ said she, ‘this creature says he is our lost son. He has been telling me how he was stolen seven years ago, and bewitched by a fairy.’

‘Indeed!’ interrupted the cobbler angrily. ‘Did he tell you this? Wait a minute, you rascal! Why I told him all about it myself only an hour ago, and then he goes off to humbug you. So you were bewitched, my son were you? Wait a bit, and I’ll bewitch you!’

So saying, he caught up a bundle of straps, and hit out at Jem so hard that he ran off crying.

The poor little dwarf roamed about all the rest of the day without food or drink, and at night was glad to lie down and sleep on the steps of a church. He woke next morning with the first rays of light, and began to think what he could do to earn a living. Suddenly he remembered that he was an excellent cook, and he determined to look out for a place.

As soon as it was quite daylight he set out for the palace, for he knew that the grand duke who reigned over the country was fond of good things.

When he reached the palace all the servants crowded about him, and made fun of him, and at last their shouts and laughter grew so loud that the head steward rushed out, crying, ‘For goodness sake, be quiet, can’t you. Don’t you know his highness is still asleep?’

Some of the servants ran off at once, and others pointed out Jem.

Indeed, the steward found it hard to keep himself from laughing at the comic sight, but he ordered the servants off and led the dwarf into his own room.

When he heard him ask for a place as cook, he said: ‘You make some mistake, my lad. I think you want to be the grand duke’s dwarf, don’t you?’

‘No, sir,’ replied Jem. ‘I am an experienced cook, and if you will kindly take me to the head cook he may find me of some use.’

‘Well, as you will; but believe me, you would have an easier place as the grand ducal dwarf.’

So saying, the head steward led him to the head cook’s room.

‘Sir,’ asked Jem, as he bowed till his nose nearly touched the floor, ‘do you want an experienced cook?’

The head cook looked him over from head to foot, and burst out laughing.

‘You a cook! Do you suppose our cooking stoves are so low that you can look into any saucepan on them? Oh, my dear little fellow, whoever sent you to me wanted to make fun of you.’

But the dwarf was not to be put off.

‘What matters an extra egg or two, or a little butter or flour and spice more or less, in such a house as this?’ said he. ‘Name any dish you wish to have cooked, and give me the materials I ask for, and you shall see.’

He said much more, and at last persuaded the head cook to give him a trial.

They went into the kitchen—a huge place with at least twenty fireplaces, always alight. A little stream of clear water ran through the room, and live fish were kept at one end of it. Everything in the kitchen was of the best and most beautiful kind, and swarms of cooks and scullions were busy preparing dishes.

When the head cook came in with Jem everyone stood quite still.

‘What has his highness ordered for luncheon?’ asked the head cook.

‘Sir, his highness has graciously ordered a Danish soup and red Hamburg dumplings.’

‘Good,’ said the head cook. ‘Have you heard, and do you feel equal to making these dishes? Not that you will be able to make the dumplings, for they are a secret receipt.’

‘Is that all!’ said Jem, who had often made both dishes. ‘Nothing easier. Let me have some eggs, a piece of wild boar, and such and such roots and herbs for the soup; and as for the dumplings,’ he added in a low voice to the head cook, ‘I shall want four different kinds of meat, some wine, a duck’s marrow, some ginger, and a herb called heal-well.’

‘Why,’ cried the astonished cook, ‘where did you learn cooking? Yes, those are the exact materials, but we never used the herb heal-well, which, I am sure, must be an improvement.’

And now Jem was allowed to try his hand. He could not nearly reach up to the kitchen range, but by putting a wide plank on two chairs he managed very well. All the cooks stood round to look on, and could not help admiring the quick, clever way in which he set to work. At last, when all was ready, Jem ordered the two dishes to be put on the fire till he gave the word. Then he began to count: ‘One, two, three,’ till he got to five hundred when he cried, ‘Now!’ The saucepans were taken off, and he invited the head cook to taste.

The first cook took a golden spoon, washed and wiped it, and handed it to the head cook, who solemnly approached, tasted the dishes, and smacked his lips over them. ‘First rate, indeed!’ he exclaimed. ‘You certainly are a master of the art, little fellow, and the herb heal-well gives a particular relish.’

As he was speaking, the duke’s valet came to say that his highness was ready for luncheon, and it was served at once in silver dishes. The head cook took Jem to his own room, but had hardly had time to question him before he was ordered to go at once to the grand duke. He hurried on his best clothes and followed the messenger.

The grand duke was looking much pleased. He had emptied the dishes, and was wiping his mouth as the head cook came in. ‘Who cooked my luncheon to-day?’ asked he. ‘I must say your dumplings are always very good; but I don’t think I ever tasted anything so delicious as they were to-day. Who made them?’

‘It is a strange story, your highness,’ said the cook, and told him the whole matter, which surprised the duke so much that he sent for the dwarf and asked him many questions. Of course, Jem could not say he had been turned into a squirrel, but he said he was without parents and had been taught cooking by an old woman.

‘If you will stay with me,’ said the grand duke, ‘you shall have fifty ducats a year, besides a new coat and a couple of pairs of trousers. You must undertake to cook my luncheon yourself and to direct what I shall have for dinner, and you shall be called assistant head cook.’

Jem bowed to the ground, and promised to obey his new master in all things.

He lost no time in setting to work, and everyone rejoiced at having him in the kitchen, for the duke was not a patient man, and had been known to throw plates and dishes at his cooks and servants if the things served were not quite to his taste. Now all was changed. He never even grumbled at anything, had five meals instead of three, thought everything delicious, and grew fatter daily.

And so Jem lived on for two years, much respected and considered, and only saddened when he thought of his parents. One day passed much like another till the following incident happened.

Dwarf Long Nose—as he was always called—made a practice of doing his marketing as much as possible himself, and whenever time allowed went to the market to buy his poultry and fruit. One morning he was in the goose market, looking for some nice fat geese. No one thought of laughing at his appearance now; he was known as the duke’s special body cook, and every goose-woman felt honoured if his nose turned her way.

He noticed one woman sitting apart with a number of geese, but not crying or praising them like the rest. He went up to her, felt and weighed her geese, and, finding them very good, bought three and the cage to put them in, hoisted them on his broad shoulders, and set off on his way back.

As he went, it struck him that two of the geese were gobbling and screaming as geese do, but the third sat quite still, only heaving a deep sigh now and then, like a human being. ‘That goose is ill,’ said he; ‘I must make haste to kill and dress her.’

But the goose answered him quite distinctly:

‘Squeeze too tight

And I’ll bite,

If my neck a twist you gave

I’d bring you to an early grave.’

Quite frightened, the dwarf set down the cage, and the goose gazed at him with sad wise-looking eyes and sighed again. ‘Good gracious!’ said Long Nose. ‘So you can speak, Mistress Goose. I never should have thought it! Well, don’t be anxious. I know better than to hurt so rare a bird. But I could bet you were not always in this plumage—wasn’t I a squirrel myself for a time?’

‘You are right,’ said the goose, ‘in supposing I was not born in this horrid shape. Ah! no one ever thought that Mimi, the daughter of the great Weatherbold, would be killed for the ducal table.’

‘Be quite easy, Mistress Mimi,’ comforted Jem. ‘As sure as I’m an honest man and assistant head cook to his highness, no one shall harm you. I will make a hutch for you in my own rooms, and you shall be well fed, and I’ll come and talk to you as much as I can. I’ll tell all the other cooks that I am fattening up a goose on very special food for the grand duke, and at the first good opportunity I will set you free.’

The goose thanked him with tears in her eyes, and the dwarf kept his word. He killed the other two geese for dinner, but built a little shed for Mimi in one of his rooms, under the pretence of fattening her under his own eye. He spent all his spare time talking to her and comforting her, and fed her on all the daintiest dishes. They confided their histories to each other, and Jem learnt that the goose was the daughter of the wizard Weatherbold, who lived on the island of Gothland. He fell out with an old fairy, who got the better of him by cunning and treachery, and to revenge herself turned his daughter into a goose and carried her off to this distant place. When Long Nose told her his story she said:

‘I know a little of these matters, and what you say shows me that you are under a herb enchantment—that is to say, that if you can find the herb whose smell woke you up the spell would be broken.’

This was but small comfort for Jem, for how and where was he to find the herb?

About this time the grand duke had a visit from a neighbouring prince, a friend of his. He sent for Long Nose and said to him:

‘Now is the time to show what you can really do. This prince who is staying with me has better dinners than any one except myself, and is a great judge of cooking. As long as he is here you must take care that my table shall be served in a manner to surprise him constantly. At the same time, on pain of my displeasure, take care that no dish shall appear twice. Get everything you wish and spare nothing. If you want to melt down gold and precious stones, do so. I would rather be a poor man than have to blush before him.’

The dwarf bowed and answered:

‘Your highness shall be obeyed. I will do all in my power to please you and the prince.’

From this time the little cook was hardly seen except in the kitchen, where, surrounded by his helpers, he gave orders, baked, stewed, flavoured and dished up all manner of dishes.

The prince had been a fortnight with the grand duke, and enjoyed himself mightily. They ate five times a day, and the duke had every reason to be content with the dwarf’s talents, for he saw how pleased his guest looked. On the fifteenth day the duke sent for the dwarf and presented him to the prince.

‘You are a wonderful cook,’ said the prince, ‘and you certainly know what is good. All the time I have been here you have never repeated a dish, and all were excellent. But tell me why you have never served the queen of all dishes, a Suzeraine Pasty?’

The dwarf felt frightened, for he had never heard of this Queen of Pasties before. But he did not lose his presence of mind, and replied:

‘I have waited, hoping that your highness’ visit here would last some time, for I proposed to celebrate the last day of your stay with this truly royal dish.’

‘Indeed,’ laughed the grand duke; ‘then I suppose you would have waited for the day of my death to treat me to it, for you have never sent it up to me yet. However, you will have to invent some other farewell dish, for the pasty must be on my table to-morrow.’

‘As your highness pleases,’ said the dwarf, and took leave.

But it did not please HIM at all. The moment of disgrace seemed at hand, for he had no idea how to make this pasty. He went to his rooms very sad. As he sat there lost in thought the goose Mimi, who was left free to walk about, came up to him and asked what was the matter? When she heard she said:

‘Cheer up, my friend. I know the dish quite well: we often had it at home, and I can guess pretty well how it was made.’ Then she told him what to put in, adding: ‘I think that will be all right, and if some trifle is left out perhaps they won’t find it out.’

Sure enough, next day a magnificent pasty all wreathed round with flowers was placed on the table. Jem himself put on his best clothes and went into the dining hall. As he entered the head carver was in the act of cutting up the pie and helping the duke and his guests. The grand duke took a large mouthful and threw up his eyes as he swallowed it.

‘Oh! oh! this may well be called the Queen of Pasties, and at the same time my dwarf must be called the king of cooks. Don’t you think so, dear friend?’

The prince took several small pieces, tasted and examined carefully, and then said with a mysterious and sarcastic smile:

‘The dish is very nicely made, but the Suzeraine is not quite complete—as I expected.’

The grand duke flew into a rage.

‘Dog of a cook,’ he shouted; ‘how dare you serve me so? I’ve a good mind to chop off your great head as a punishment.’

‘For mercy’s sake, don’t, your highness! I made the pasty according to the best rules; nothing has been left out. Ask the prince what else I should have put in.’

The prince laughed. ‘I was sure you could not make this dish as well as my cook, friend Long Nose. Know, then, that a herb is wanting called Relish, which is not known in this country, but which gives the pasty its peculiar flavour, and without which your master will never taste it to perfection.’

The grand duke was more furious than ever.

‘But I WILL taste it to perfection,’ he roared. ‘Either the pasty must be made properly to-morrow or this rascal’s head shall come off. Go, scoundrel, I give you twenty-four hours respite.’

The poor dwarf hurried back to his room, and poured out his grief to the goose.

‘Oh, is that all,’ said she, ‘then I can help you, for my father taught me to know all plants and herbs. Luckily this is a new moon just now, for the herb only springs up at such times. But tell me, are there chestnut trees near the palace?’

‘Oh, yes!’ cried Long Nose, much relieved; ‘near the lake—only a couple of hundred yards from the palace—is a large clump of them. But why do you ask?’

‘Because the herb only grows near the roots of chestnut trees,’ replied Mimi; ‘so let us lose no time in finding it. Take me under your arm and put me down out of doors, and I’ll hunt for it.’

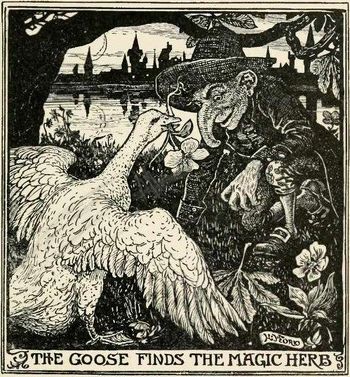

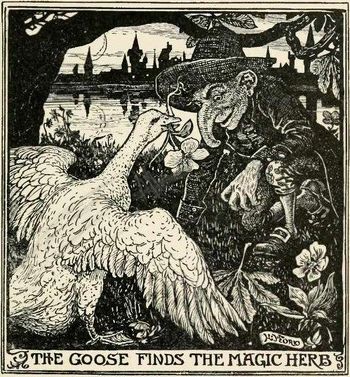

He did as she bade, and as soon as they were in the garden put her on the ground, when she waddled off as fast as she could towards the lake, Jem hurrying after her with an anxious heart, for he knew that his life depended on her success. The goose hunted everywhere, but in vain. She searched under each chestnut tree, turning every blade of grass with her bill—nothing to be seen, and evening was drawing on!

Suddenly the dwarf noticed a big old tree standing alone on the other side of the lake. ‘Look,’ cried he, ‘let us try our luck there.’

The goose fluttered and skipped in front, and he ran after as fast as his little legs could carry him. The tree cast a wide shadow, and it was almost dark beneath it, but suddenly the goose stood still, flapped her wings with joy, and plucked something, which she held out to her astonished friend, saying: ‘There it is, and there is more growing here, so you will have no lack of it.’

The dwarf stood gazing at the plant. It gave out a strong sweet scent, which reminded him of the day of his enchantment. The stems and leaves were a bluish green, and it bore a dark, bright red flower with a yellow edge.

‘What a wonder!’ cried Long Nose. ‘I do believe this is the very herb which changed me from a squirrel into my present miserable form. Shall I try an experiment?’

‘Not yet,’ said the goose. ‘Take a good handful of the herb with you, and let us go to your rooms. We will collect all your money and clothes together, and then we will test the powers of the herb.’

So they went back to Jem’s rooms, and here he gathered together some fifty ducats he had saved, his clothes and shoes, and tied them all up in a bundle. Then he plunged his face into the bunch of herbs, and drew in their perfume.

As he did so, all his limbs began to crack and stretch; he felt his head rising above his shoulders; he glanced down at his nose, and saw it grow smaller and smaller; his chest and back grew flat, and his legs grew long.

The goose looked on in amazement. ‘Oh, how big and how beautiful you are!’ she cried. ‘Thank heaven, you are quite changed.’

Jem folded his hands in thanks, as his heart swelled with gratitude. But his joy did not make him forget all he owed to his friend Mimi.

‘I owe you my life and my release,’ he said, ‘for without you I should never have regained my natural shape, and, indeed, would soon have been beheaded. I will now take you back to your father, who will certainly know how to disenchant you.’

The goose accepted his offer with joy, and they managed to slip out of the palace unnoticed by anyone.

They got through the journey without accident, and the wizard soon released his daughter, and loaded Jem with thanks and valuable presents. He lost no time in hastening back to his native town, and his parents were very ready to recognise the handsome, well-made young man as their long-lost son. With the money given him by the wizard he opened a shop, which prospered well, and he lived long and happily.

I must not forget to mention that much disturbance was caused in the palace by Jem’s sudden disappearance, for when the grand duke sent orders next day to behead the dwarf, if he had not found the necessary herbs, the dwarf was not to be found. The prince hinted that the duke had allowed his cook to escape, and had therefore broken his word. The matter ended in a great war between the two princes, which was known in history as the ‘Herb War.’ After many battles and much loss of life, a peace was at last concluded, and this peace became known as the ‘Pasty Peace,’ because at the banquet given in its honour the prince’s cook dished up the Queen of Pasties—the Suzeraine—and the grand duke declared it to be quite excellent.

Unknown.

La storia del nano Naso Lungo

È un grave errore pensare che fate, streghe, maghi e gente simile vivessero solo nei paesi orientali e in tempi come quelli del califfo Haroun Al-Raschid. Le fate e i loro simili appartengono a ogni paese e a ogni epoca e senza dubbio potremmo vederne in abbondanza, se solo sapessimo come.

Un paio di secoli fa in una grande città della Germania vivevano un ciabattino e sua moglie. Erano poveri, ma gran lavoratori. L’uomo sedeva tutto il giorno al suo deschetto all’angolo della strada e riparava qualunque scarpa gli portassero. La moglie vendeva la frutta e la verdura del loro giardino sulla piazza del mercato e, siccome era sempre linda e pinta e i suoi prodotti erano allettanti, aveva sempre molti clienti.

La coppia aveva un figlio di nome Jem. Un ragazzo di dodici anni di bell’aspetto, alto per la sua età. Era solito sedere al mercato con la madre e consegnare a domicilio ciò che la gente comprava da lei, per cui spesso lo ricompensavano con un bel fiore o una fetta di torta o talvolta qualche monetina.

Un giorno Jem e sua madre sedevano come il solito nella piazza del mercato con un’abbondanza di buone erbe e di verdure sparse sul banco e con piccoli canestri di primizie come pere, mele e albicocche. Jem annunciava le mercanzie a piena voce:

“Da questa parte, signori! Guardate questi bei cavoli e queste erbe fresche! Le prime mele, signore, le prime pere e albicocche e tutto a buon prezzo. Venire e comprate!”

Mentre gridava, una vecchia attraverso la piazza del mercato. Era una stracciona, con un piccolo viso affilato, tutta grinzosa, con gli occhi rossi e sottile naso adunco che quasi le toccava il mento. Si appoggiava a un alto bastoncino e zoppicava, trascinava i piedi e inciampava come se ogni momento stesse per cadere sul naso.

Si avvicinò in tale maniera finché giunse al banco presso cui stavano Jem e sua madre e lì si fermò.

“Sei Hannah, la venditrice di erbe?” chiese con voce roca mentre scuoteva su e giù la testa.

“Sì, sono io,” fu la risposta, “Posso servirvi?”

“Vedremo, vedremo! Lasciami vedere quelle erbe. Mi chiedo se tu abbia ciò che voglio.” disse la donna mentre ficcava le orribili mani scure nel canestro delle erbe e cominciava a rivoltare tutte le erbe ordinatamente impacchettate con quelle sue dita magre, mettendosele spesso sotto il naso e annusandole.

La moglie del ciabattino era disgustata nel vedere un trattamento simile, ma non osava parlare. Quando la vecchia megera ebbe rivoltato l’intero canestro, borbottò: “Merce cattiva, merce cattiva, era molto meglio cinquant’anni fa – tutto cattivo.”

Ciò fece arrabbiare molto Jem.

“Siete una vecchia molto maleducata,” strillò, “prima avete buttato all’aria tutte le nostre belle erbe con quelle vostre orribili dita scure e poi le avete annusate con quel vostro naso lungo cosicché nessun altro le vorrà comprare e poi dite che è tutta merce cattiva sebbene il cuoco stesso del duca compri tutte le erbe da noi.”

La vecchia guardò duramente il ragazzino impertinente, rise in modo sgradevole e disse:

“Così non ti piace il mio naso lungo, figliolo? Ebbene, ne avrai uno tu stesso, lungo proprio fino al mento.”

Mentre parlava frugò nel canestro dei cavoli, li tirò su uno dopo l’altro, li spremette forte e li gettò di nuovo giù, borbottando di nuovo: “Merce cattiva, merce cattiva.”

“Non scrollate la testa in quell’orribile maniera,” la pregò ansiosamente Jem, “Il vostro collo è sottile come un gambo di cavolo e potrebbe facilmente spezzarsi così la vostra testa cadrebbe nel canestro e allora chi comprerebbe più niente?”

“Non ti piace il mio collo?” rise la vecchia, “allora tu non avrai altro che una testa ficcata tra le spalle così che tu possa essere sicuro non cada.”

“Non dite cose insensate al bambino.” disse infine la madre. “Se volete pagare, per favore sbrigatevi perché state tenendo lontani gli altri clienti.”

“Benissimo, farò come dici.” disse la vecchia con uno sguardo rabbioso. “Comprerò questi sei cavoli ma, come vedi, posso camminare solo con il bastone e non posso portare altro. Che tuo figlio li porti a casa per me e lo pagherò per il disturbo.”

Al ragazzino l’idea non piaceva e cominciò a piangere perché aveva paura della vecchia, ma la madre gli ordinò di andare perché pensava fosse sbagliato non aiutare un essere così vecchio e debole; così, piangendo, il ragazzino mise i cavoli in un canestro e seguì la vecchia attraverso la piazza del mercato.

Ci volle più di mezz’ora per arrivare in una parte lontana della piccola città, ma alla fine la vecchia si fermò davanti a una casetta semi diroccata. Estrasse dalla tasca un vecchio uncino arrugginito e lo conficcò in un buco della porta, che si aprì all’improvviso. Quale fu la sorpresa di Jem quando entrò! La casa era arredata splendidamente, i muri e la cantina erano di marmo, i mobili di ebano intarsiato d’oro e di pietre preziose, il pavimento era di un vetro così liscio e scivoloso che il ragazzino cadde più di una volta.

La vecchia prese un fischietto d’argento e soffiò finché il suono risuonò per la casa. Immediatamente scesero dalle scale alcuni maialini d’India, ma Jem pensò che fosse piuttosto strano che camminassero tuti sulle zampe posteriori, calzando come scarpe gusci di noce e indossando abiti maschili, mentre persino i loro cappelli erano i più alla moda.

“Dove sono le mie pantofole, lazzaroni?” strillò la vecchia, colpendoli con il bastoncino. “Quanto a lungo dovrò restare qui, aspettandole?”

Si precipitarono al piano superiore e ritornarono con un paio di gusci di noci di cocco foderate di pelle, che la vecchia calzò. A questo punto sparirono la zoppìa e lo strascichio dei piedi. Gettò il bastone e camminò vivacemente sul pavimento di vetro, trascinandosi dietro il piccolo Jem. Alla fine si fermò in una stanza che sembrava una cucina, visto che era così piena di pentole e di padelle, ma i tavoli erano di mogano e i divani e le poltrone erano coperti con le stoffe più sontuose.

“Siediti.” disse la vecchia garbatamente e spinse Jem nell’angolo di un divano e gli mise davanti un tavolo. “Siediti, hai fatto tanta strada e hai portato un carico pesante, devo darti qualcosa per il disturbo. Aspetta un attimo e ti darò un po’ di zuppa così buona che te la rammenterai per tutto il resto della vita.”

Così dicendo, fischiò di nuovo. Prima vennero porcellini d’India in abiti da uomo. Avevano indossato dei grembiuloni da cucina e alla cintura portavano coltelli da scalco, mestoli da salsa e altre cose. Poi balzarono dentro un certo numero di scoiattoli. Anch’essi camminavano sulle zampe posteriori, con indosso pantaloni alla turca e con berrettini di velluto verde sulle teste. Sembravano sguatteri di cucina perché si arrampicarono sui muri e portarono giù pentole e padelle, uova, farina, burro e erbette che portarono alla stufa. Lì la vecchia era indaffarata e Jem poté vedere che stava cucinando per lui qualcosa di veramente speciale. Alla fine la minestra cominciò a gorgogliare e a bollire e lei tolse la pentola e ne versò il contenuto in una scodella d’argento, che mise davanti a Jem.

“Ecco, ragazzo mio,” disse, “mangia questa zuppa e poi avrai da me qualunque cosa vorrai. Sarai anche un bravo cuoco, ma le autentiche erbette, le autentiche erbette non le troverai mai. Perché tua madre non le ha messe nel canestro?”

Il ragazzino non aveva idea di che cosa stesse parlando, ma comprendeva bene la zuppa, che aveva trovato assai deliziosa. Sua madre spesso gli aveva dato cose buone, ma nulla di buono come questa. L’aroma delle erbette e delle spezie emanava dalla scodella e la zuppa sapeva di dolce e aspro nel medesimo tempo ed era molto forte. Mentre la stava finendo, i maialini d’India accesero un po’ di incenso arabo il quale pian piano riempì la stanza di nuvole di vapore blu. Diventarono sempre più dense e il profumo quasi sopraffece il ragazzo. Ricordava a se stesso che doveva tornare da sua madre, ma per quanto tentasse di sollevarsi per andare, ricadeva indietro insonnolito e alla fine cadde addormentato in un angolo del divano.

Lo visitarono strani sogni. Pensò che la vecchia gli avesse tolto i vestiti e lo avesse avvolto in una pelle di scoiattolo e che fosse andato con gli altri scoiattoli e porcellini d’India, che erano tutti assai piacevoli e di buone maniere, e aspettassero la vecchia.

Dapprima imparò a pulire le sue pantofole di noci di cocco con olio e a strofinarle. Poi imparò ad afferrare piccole falene diurne e a strofinarle sui setacci più sottili, e con la farina che ne ricavava, faceva un morbido pane per la vecchia sdentata.

In questa maniera passò da un tipo di servizio a un altro, trascorrendo un anno in ciascuno, finché al quarto anno fu promosso in cucina. Qui fece carriera da vice sguattero a pasticciere capo e raggiunse la più grande perfezione. Poteva preparare tutti i piati più complicati e duecento diversi tipi di sformati, zuppe aromatizzate con ogni sorta di erbe – aveva imparato tutto, e in fretta e bene.

Quando ebbe vissuto sette anni con la vecchia, essa un giorno gli ordinò, mentre se ne stava andando, di uccidere e spennare un pollo, farcirlo di erbe e arrostirlo alla perfezione per quando fosse tornata. E lui lo fece secondo le regole. Tirò il collo al pollo, lo tuffò nell’acqua bollente, lo spennò accuratamente e strofinò la pelle fino a renderla bella liscia. Poi andò a prendere le erbe per farcirlo. Nel magazzino si accorse di un armadio semi aperto che non rammentava di aver mai visto prima. Vi sbirciò e vide un po’ di canestri dai quali proveniva un profumo intenso e piacevole. Ne aprì uno e vi trovò un’erba davvero insolita. Gli steli e le foglie erano di un verde azzurrognolo e in cima c’era un fiorellino di un rosso intenso e luminoso, bordato di giallo. Fissò il fiore, lo annusò e si accorse che aveva il medesimo, strano profumo della zuppa che la vecchia gli aveva servito. Ma il profumo era così intenso che cominciò a starnutire, ancora e ancora, e alla fine si svegliò!

Giaceva sul divano della vecchia e si guardò attorno sorpreso. ‘Beh, che razza di sogni strani uno deve fare!’ si disse. “Giurerei di essere stato uno scoiattolo, un compagno di porcellini d’India e altre creature e di essere diventato anche un abile cuoco. Chissà come riderà mia madre quando glielo racconterò! Ma non vorrei che mi rimproverasse per aver dormito in una casa sconosciuta invece di aiutarla al mercato!’

Balzò in piedi e si preparò ad andarsene; dopo quel lungo sonno le membra gli sembravano rigide, specialmente il collo perché non poteva muovere facilmente la testa, e rise della propria stupidità nel rendersi conto di essere così insonnolito da battere il naso contro il muro o gli armadi. Gli scoiattoli e i porcellini d’India corsero gemendo davanti a lui, come se volessero andarsene anche loro, e quando raggiunse la porta li pregò di venire, ma si volsero tutti e corsero di nuovo in casa.

Quella zona della città era in periferia e Jem non conosceva le numerose viuzze; era confuso dalla loro tortuosità e dalla folla che sembrava eccitata per qualche spettacolo. Da ciò che sentiva, suppose che stessero andando a vedere un nano perché li sentiva gridare: “Guarda quel brutto nano!” “Che naso lungo ha e guarda com’è ficcata tra le spalle la sua testa, guarda le sue brutte mani scure!” se non avesse avuto fretta di tornare dalla madre, sarebbe andato anche lui perché gli piaceva vedere giganti e nani e creature simili.

Quando raggiunse la piazza del mercato fu piuttosto stupito. Sua madre sedeva là, con la sua frutta di buona qualità nei canestri, così pensò di non aver dormito tanto a lungo, però rimase colpito perché era triste, al punto di non curarsi dei passanti e di sedere con la testa appoggiata a una mano; come le fu più vicino, pensò che gli sembrasse più pallida del solito.

Esitò sul da farsi, ma alla fine scivolò dietro di lei, le posò una mano sul braccio e disse: “Mamma, che succede? Sei arrabbiata con me?”

Lei si voltò rapidamente e balzò in piedi con un urlo di raccapriccio.

“Che cosa vuoi da me, orribile nano?” gridò, “Vattene via, non posso sopportare questi scherzi.”

“Mamma cara, che ti succede?” ripeté Jem, molto spaventato. “Non stai bene. Vuoi mandare via tuo figlio?”

“Ti ho già detto di andartene,” rispose Hanna, molto arrabbiata. “Non otterrai nulla da me con i tuoi giochetti, mostriciattolo.”

‘Povero me! Deve essere impazzita,’ mormorò tra sé il ragazzo, “Come posso riuscire a condurla a casa? Mamma carissima, guardami. Non vedi che sono tuo figlio Jem?”

“Beh, avete mai visto tanta impudenza?” chiese la donna, rivolgendosi a una vicina. “Vedi questo spaventoso nano – ci crederesti che voglia io pensi sia mio figlio Jem?”

Allora tutte le donne del mercato la circondarono e parlarono tutte insieme, rimproverandolo il più duramente possibile, e dissero che era una vergogna prendersi gioco di madama Hanna, che non si era mai ripresa dalla perdita del suo bellissimo figlio, portatole via sette anni prima, e minacciarono di gettarsi su Jem e graffiarlo ben bene se non se ne fosse andato via subito.

Il povero Jem non sapeva che fare. Era certo di essere andato al mercato con la madre solo quella mattina, di averla aiutata a piazzare la bancarella, di essere andato a casa della vecchia dove aveva mangiato un po’ di zuppa e fatto un sonnellino, e adesso, una volta tornato indietro, gli stavano parlando di sette anni. E lo chiamavano orrido nano! Che cosa gli era accaduto? Quando gli fu chiaro che la madre non volesse aver nulla che fare con lui, ricacciò indietro le lacrime e se ne andò tristemente lungo la strada verso la bottega di suo padre.

‘Vedremo se mi riconoscerà’ pensò, ‘starò vicino alla porta e gli parlerò.’

Quando fu presso la bottega, si mise sulla soglia e guardò dentro. Il ciabattino era così impegnato a lavorare che non lo vide per un po’ di tempo ma, capitandogli di guadare su, gettò un’occhiata al visitatore e, lasciando cadere per terra le scarpe, il filo e tutto il resto, gridò orripilato: “Cielo! Che roba è?”

“Buonasera, padrone” disse il ragazzo mentre faceva un passo all’interno. “Come state?”

“Assai male, signorino,” rispose il padre con sorpresa di Jem perché non sembrava riconoscerlo. “Gli affari vanno male, sono solo, sto diventando vecchio e un aiutante costa.”

“Non avete un figlio al quale insegnare per gradi il vostro mestiere?” chiese Jem.

“Ne avevo uno, si chiamava Jem e adesso sarebbe stato un ragazzo alto e robusto di vent’anni, in grado di aiutarmi. Perché quando ne aveva solo dodici, era sveglio e veloce, aveva imparato molte cosette ed era anche un ragazzino attraente e piacevole, e conquistava i clienti. Beh, così va il mondo!”

“Dov’è vostro figlio?” chiese Jem, con voce tremante.

“Lo sa il cielo!” rispose l’uomo, “Sette anni fa è stato rapito nella piazza del mercato e non abbiamo più avuto sue notizie.”

“SETTE ANNI FA!” gridò Jem, inorridito.

“Sì, proprio sette anni fa, sebbene mi sembri ieri che mia moglie sia tornata urlando e piangendo, dicendo che nostro figlio non era tornato per tutto il giorno. Io ho sempre pensato e detto che gli sia accaduto qualcosa. Jem era un ragazzino bellissimo, benvoluto da tutti, e mia moglie era così orgogliosa di lui, e gli piaceva portare le verdure e altre cose al grande mercato, dove era vezzeggiato e benvoluto. Io ero solito dire: ‘Fai attenzione, la città è grande, è piena di gente cattiva, tieni d’occhio Jem.’ E così è successo; perché un giorno una vecchia è venuta e ha comprato un po’ di roba, più di quanta ne potesse portare; così mia moglie, d’animo gentile, le ha prestato il ragazzino e da allora non l’abbiamo mai più visto.”

“E avete detto che è stato sette anni fa?”

“Sì, sette anni; abbiamo gridato il suo nome, siamo andati di casa in casa. Molti conoscevano il nostro bel ragazzo e gli volevano bene, ma è stato tutto inutile. Nessuno sembrava conoscesse la vecchia che ha acquistato le verdure; solo una vecchia di circa novant’anni ha detto che si sarebbe potuto trattare della fata Herbaline, che viene in città una volta ogni cinquant’anni a fare acquisti.”

Alle parole del padre, tutto si fece più chiaro nella mente di Jem e ora vide che non aveva sognato, ma che sotto forma di scoiattolo aveva davvero servito per sette anni la vecchia. A questo pensiero il suo cuore si colmò di rabbia. Gli erano stati rubati dette anni della sua fanciullezza e che cosa ne aveva avuto in cambio? Imparare a lustrare noci di cocco, a pulire pavimenti di vetro e ad apprendere l’arte della cucina dai porcellini d’India! Rimase lì pensieroso finché infine il padre gli chiese:

“C’è qualcosa che osso fare per voi, giovane signore? Posso farvi un paio di pantofole o forse” disse con un sorriso, “un astuccio per il vostro naso?”

“Che cosa avete contro il mio naso?” chiese Jem. “E perché dovrei avere un astuccio per esso?”

“Beh, i gusti non si discutono,” rispose il ciabattino, “ma devo dirvi che, se avessi un naso simile, vorrei un bell’astuccio di pelle rossa per esso. Ecco qui un bell’articolo, e pensate che protezione sarebbe per voi. Per come stanno le cose, dovete urtare continuamente contro le cose.”

Il ragazzo rimase ammutolito per la paura. Si tastò il naso. Era grosso e lungo circa due spanne. Dunque la vecchia aveva mutato il suo aspetto, ecco perché sua madre non lo aveva riconosciuto e chiamato orrido nano!

“Padrone, avete uno specchio in cui possa guardarmi?” disse.

“Giovane signore,” fu la risposta, “il vostro aspetto è difficilmente cosa di cui essere fiero, e non serve che perdiate tempo a guardarvi in uno specchio. Oltretutto io non ne ho qui e se ne volete uno, fareste meglio a chiedere a Urban il barbiere, che abita oltre la via, di prestarvene uno. Buongiorno.”

Così dicendo, spinse gentilmente Jem in strada, chiuse la porta e tornò al lavoro.

Jem si diresse dal barbiere, che aveva conosciuto ai vecchi tempi.

“Buongiorno, Urban” disse, “potrei guardarmi per un momento nel vostro specchio?”

“Con piacere,” disse il barbiere, ridendo, e anche tutte le persone nella sua bottega risero. “Siete un bel giovanotto con quel vostro collo da cigno, le mani candide e un piccolo naso. Nessuna meraviglia se siate piuttosto vanitoso; guardatevi quanto vi pare.”

Così parlò il barbiere e risolini percorsero la bottega. Nel frattempo Jem si era messo davanti allo specchio e osservava tristemente il proprio riflesso. Gli salirono le lacrime agli occhi.

‘Non mi meraviglia che tu non abbia riconosciuto di nuovo tuo figlio, cara mamma,’ pensò, ‘non è come quello alla cui vista ti sentivi tanto orgogliosa.’

Gli occhi erano piuttosto piccoli, come quelli di un maiale, il naso era enorme e gli pendeva sulla bocca e sul mento, la gola sembrava completamente sparita e la testa era ficcata rigidamente in mezzo alle spalle. Non era più alto di quanto lo era stato sette anni prima, quando aveva poco più di dodici anni, ma si era accresciuto in larghezza e il dorso e il petto sviluppati in protuberanze come grandi sacchi. Le gambe erano corte e esili, ma le braccia erano lunghe come quelle di un uomo ben sviluppato, con ampie mani scure e lunghe dita ossute.

Poi si rammentò del mattino in cui aveva visto per la prima volta la vecchia e le minacce che gli aveva ricolto; senza dire una parola uscì dalla bottega del barbiere.

Decise di andare di nuovo da sua madre e la trovò immobile nella piazza del mercato. La pregò di ascoltarlo con calma e le rammentò il giorno in cui era andato via con la vecchia e molte cose della sua infanzia, e le disse come la fata lo avesse stregato e lui l’avesse servita per sette anni. Hanna non sapeva che cosa pensare, la storia era così strana; le sembrava impossibile pensare che il suo bel bambino e questo orribile nano fossero la medesima persona. Infine decise di andare a parlarne con il marito. Raccolse i canestri, disse a Jem di seguirla e andò difilata alla bottega del ciabattino.

Disse: “Guarda, questo essere dice di essere il nostro figliolo perduto. Mi ha raccontato di essere stato rapito sette anni fa e stregato da una fata.”

Il ciabattino la interruppe rabbiosamente: “Ma davvero! Ti ha detto ciò? Aspetta un minuto, briccone! Perché io gliel’ho raccontato solo un’ora fa e allora lui è venuto a ingannarti. Così saresti stato stregato e saresti mio figlio? Aspetta un attimo, che ti stregherò io!”

Così dicendo, afferrò una manciata di cinghie e colpì così duramente Jem che corse via piangendo.

Il povero nanerottolo vagò per il resto del giorno senza cibò né bevande e quando fu notte fu contento di sdraiarsi a dormire sui gradini di una chiesa. Si svegliò il mattino seguente alle prime luci e cominciò a pensare a come avrebbe potuto guadagnarsi da vivere. Improvvisamente si rammentò di essere un cuoco eccellente e decise di cercarsi un posto di lavoro.

Appena vi fu abbastanza luce, si diresse a palazzo perché sapeva che il granduca che governava il paese amava le cose buone.

Quando ebbe raggiunto il palazzo, tutti I servitor gli si affollarono intorno e si presero gioco di lui; alla fine le loro grida e le loro risate divennero così rumorose che il maggiordomo corse fuori, gridando: “Bontà divina, state calmi: Non sapete che sua altezza sta ancora dormendo?”

Alcuni servitori corsero via subito e altri additarono Jem.

Per la verità anche il maggiordomo trovava difficile resistere alle risate a quella buffa vista, ma ordinò ai servitori di andarsene e condusse il nano nella propria stanza.

Quando gli sentì chiedere un posto come cuoco, disse: “Devi esserti sbagliato, ragazzo mio. Penso tu voglia essere il nano del granduca, vero?”

Jem rispose: “No, signore. Sono un cuoco esperto e se gentilmente voleste condurmi dal capo cuoco, lui potrebbe trovarmi utile.”

“Ebbene, sia come vuoi tu, ma, credimi, avresti avuto un posto più agevole come nano del granduca.”

Così dicendo, il maggiordomo lo condusse nella stanza del capo cuoco.

“Signore,” chiese Jem mentre s’inchinava fino a toccare il pavimento con il naso, “volete un cuoco esperto?”

Il capo cuoco lo squadrò dalla testa ai piedi e scoppiò in una risata.

“Un cuoco, tu! Credi che le nostre stufe siano così basse che tu possa guardare dentro una loro qualsiasi pentola? Oh, mio caro e piccolo amico, chi ti ha mandato da me voleva prendersi gioco di te.”

Il nano però non si lasciò scoraggiare.

“Che cosa volete che importino un uovo o due in più, o un po’ di burro o di farina, o qualche spezia in più o in meno in una casa come questa?” disse. “Nominate qualsiasi piatto vogliate sia cucinato e datemi gli ingredienti che vi chiedo, vedrete.”

Aggiunse molto altro e alla fine convinse il capo cuoco a dargli una possibilità.

Andarono in cucina – un posto enorme con almeno venti fuochi sempre accesi. Attraverso la stanza scorreva un rivolo di acqua limpida in cui a un’estremità vi erano pesci vivi. Tutto in cucina era di ottima fattura e sciami di cuochi e di aiutanti erano indaffarati nella preparazione di piatti.

Quando il capocuoco entrò con Jem, ognuno rimase immobile.

“Che cosa ha ordinato sua altezza per pranzo?” chiese il capo cuoco.

“Sua altezza ha graziosamente ordinato una zuppa danese e zampe d’oca con cavolo rosso e pasticci fatti a mano alla maniera di Amburgo, signore.”

Il capo cuoco disse. “Ebbene, hai sentito, ti senti in grado di preparare quei piatti? Non che tu possa realizzare i pasticci, perché sono una ricetta segreta.

“Tutto qui!” disse Jem, che aveva cucinato spesso entrambi i piatti. “Niente di più facile. Datemi alcune uova, un pezzo di cinghiale, e tali e quali radici e erbe e per la zuppa; e altrettanto per i pasticci.” aggiunse a bassa voce al capo cuoco, “Mi serviranno quattro differenti tipi di carne, un po’ di vino, midollo d’anatra, un po’ di zenzero e un’erba detta della salute.”

“Dove hai imparato a cucinare?” chiese sbalordito il capo cuoco. “Questi sono gli ingredienti giusti, ma non abbiamo mai usato l’erba della salute che, ne sono certo, deve essere un miglioramento.”

E così a Jem fu permesso di provarci. Non poteva giungere facilmente all’altezza della cucina, ma mettendo un largo asse su due sedie, ci riuscì benissimo. Tutti i cuochi gli stavano intorno guardando e non potevano che ammirare la sveltezza e l'abilità con cui lavorava. Alla fine, quando tutto fu pronto, Jem ordinò che i due piatti fossero tenuti sul fuoco fino a quando lo avesse detto lui. Poi cominciò a contare: “Uno, due, tre,” finché giunse a cinquecento quando gridò: “Adesso!” Le pentole furono tolte e lui invitò il capo cuoco ad assaggiare.

Il primo cuoco prese un cucchiaio d’oro, lo lavò e lo asciugò, poi lo porse al capo cuoco il quale sia avvicinò solennemente, assaggiò i piatti e schioccò le labbra. “Eccellente, davvero!” esclamò. “Sei di certo un maestro in quest’arte, piccolo amico, e l’erba della salute conferisce un gusto particolare.”

Mentre stava parlando, entrò un valletto del duca e disse che sua altezza era pronto per il pranzo, che gli fu subito servito su piatti d’argento. Il capo cuoco condusse Jem nella propria stanza, ma ebbe a malapena il tempo di interrogarlo prima che gli fosse ordinato di andare subito dal granduca. Si affrettò a indossare gli abiti migliori e seguì il messaggero.

Il granduca appariva molto compiaciuto, aveva vuotato i piatti e si stava asciugando la bocca quando entrò il capo cuoco. “Chi ha cucinato oggi il mio pranzo?” chiese. “Devo dire che i vostri pasticci sono sempre buoni, ma non pensavo che avrei mai gustato qualcosa di tanto delizioso come lo erano oggi. Chi li ha fatti?”

“È una storia strana, vostra altezza, “disse il cuoco e gli raccontò tutta la faccenda, che sorprese tanto il duca, il quale mandò a chiamare il nano e gli rivolse molte domande. Naturalmente Jem non poteva dire di essere stato tramutato in uno scoiattolo, ma gli disse di essere senza genitori e di aver imparato a cucinare da una vecchia.

Il granduca gli disse: “Se resterai con me, riceverai cinquanta ducati l’anno, oltre a un vestito nuovo e a due paia di pantaloni. Dovrai impegnarti a cucinare tu stesso il mio pranzo e a curare ciò che vorrò per cena, e sarai nominato assistente del capo cuoco.”

Jem si inchinò fino a terra e promise di obbedire in tutto al nuovo padrone.

Non perse tempo nel mettersi al lavoro e tutti furono contenti di averlo in cucina perché il duca non era un uomo paziente ed era famoso per gettare stoviglie e piatti contro i cuochi e i servi se ciò che gli veniva servito non era di suo gusto. Adesso tutto era cambiato. Non brontolava più per ogni cosa, faceva cinque pasti invece di tre, trovando tutto delizioso, e ingrassava di giorno in giorno.

Jem visse così per due anni, assai rispettato e tenuto in considerazione, e si rattristava solo quando pensava ai genitori. I giorni passavo l’uno come l’altro finché accadde il seguente incidente.

Nano Naso Lungo – così lo chiamavano – si ingegnava il più possibile a fare da sé, e ogni volta in cui gli era permesso, andava al mercato a procurarsi il pollame e la frutta. Una mattina era al mercato delle oche, osservando quelle più belle grasse. Nessuno adesso si permetteva di ridere al suo apparire, era conosciuto come il cuoco personale del duca e ogni allevatrice di oche era onorata se il suo naso si volgeva nella sua direzione.

Notò una donna che sedeva in disparte con un certo numero di oche, ma non strillava o le elogiava come le altre. Andò da lei, valutò e soppesò le sue oche e, trovandole assai buone, ne acquistò tre e la gabbia in cui infilarle, se la mise sulle spalle e riprese la propria strada.

Mentre camminava, lo colpì il fatto che due delle oche stessero gloglottando e strillando, mentre la terza restava immobile, lasciandosi solo sfuggire di tanto in tanto un singhiozzo, come un essere umano. ‘Quell’oca è malata,’ si disse, ‘dovrò affrettarmi a ucciderla e a condirla.’

Ma l’oca gli rispose chiaramente:

”Stringi troppo

E io morderò,

Se mi torcerai il collo

presto alla tomba ti porterò.

Piuttosto spaventato, il nano depose la gabbia e l’oca lo fissò con sguardo triste poi singhiozzò di nuovo.

“Buon Dio!” esclamò Naso Lungo, “Così puoi parlare, madama oca. Non lo avrei mai pensato! Ebbene, non agitarti. So far di meglio che ferire un così raro uccello. Scommetto che non hai sempre avuto addosso queste piume - non sono stato forse io uno scoiattolo per un po’ di tempo?”

“Hai ragione” disse l’oca, “nel supporre che io non sia nata con questo orribile aspetto. Ah! Nessuno avrebbe pensato che Mimi, la figlia del grande Weatherbold, potesse essere uccisa per la tavola del duca.”

“State tranquilla, madamigella Mimi,” la confortò Jem “Come è sicuro che io sia un uomo onesto e l’assistente del capo cuoco di sua altezza, nessuno vi farà del male. Vi preparerò una cesta nella mia stanza, sarete ben nutrita e io verrò a parlare con voi quanto più potrò. E dirò a tutti agli altri cuochi che sto ingrassando un’oca per il granduca con cibo assai speciale e alla prima occasione buona, vi libererò.”

L’oca lo ringraziò con le lacrime agli occhi e il nano mantenne la parola. Uccise per cena le altre due oche, ma costruì un piccolo rifugio per Mimi in una delle proprie stanze, fingendo di volerla tenere d’occhio mentre ingrassava. Trascorreva il tempo che gli restava parlando con lei e confortandola, e la nutriva con i piatti più prelibati. Si confidarono l’un l’altra le loro storie e Jem apprese che l’oca era la figlia del mago Weatherbold, che viveva sull’isola di Gothland. Era stato giocato da una vecchia fata, che aveva avuto la meglio su di lui con astuzia e tradimento e per vendicarsi aveva trasformato sua figlia in un’oca e l’aveva portata in quel luogo lontano. Quando Naso Lungo le narrò la propria storia, lei disse:

“Ne so un po’ di queste cose, e ciò che dici mi dimostra eri sotto l’influsso di un incantesimo con le erbe – ti posso dire che se potrai trovare l’erba il cui odore ti ha svegliato, l’incantesimo sarà spezzato.”

Ciò confortò poco Jem, perché come e dove avrebbe trovato l’erba?

Nel frattempo il granduca aveva ricevuto la visita di un principe vicino, amico suo. Mandò a chiamare Naso Lungo e gli disse:

“È il momento di dimostrare ciò che realmente sai fare. Il principe che dimora presso di me gode delle migliori cene meglio di chiunque altro eccetto me ed è un grande intenditore di cucina. Finché sarà qui, sarà tua cura che la mia tavola sia servita in maniera tale da sorprenderlo costantemente. E nel medesimo tempo, pena il mio disappunto, premurati che nessun piatto vi compaia due volte. Fai tutto ciò che vuoi e non badare a spese. Se vorrai fondere oro o pietre preziose, fallo. Preferirei piuttosto diventare povero che dover arrossire di fronte a lui.”

Il nano si inchinò e rispose:

“Vostra altezza sarà obbedita. Farò tutto ciò che è in mio potere per compiacere voi e il principe.”

Da quel momento il piccolo cuoco fu visto a malapena tranne che nella cucina in cui, circondato dagli aiutanti, dava ordini, cuoceva al forno, cuoceva in pentola, insaporiva e serviva ogni genere di piatti.

Il principe rimase due settimane presso il granduca e gradì molto. Mangiavano cinque volte il giorno e il duca aveva ogni ragione per essere contento dei talenti del nano perché vedeva quanto apparisse soddisfatto l’ospite. Il quindicesimo giorno il duca mandò a chiamare il nano e lo presentò al principe.

“Sei un cuoco magnifico,” disse il principe, “e certamente sai quanto ciò vada bene. In tutto il tempo in cui sono stato qui non hai mai replicato un piatto ed era tutto eccellente. Ma dimmi, perché non hai mai servito la regina di tutte le portate, la Pietanza Sovrana?”

Il nano s’impaurì perché non aveva mai sentito prima di questa Regina delle Pietanze, ma non perse la presenza di spirito e rispose:

“Ho atteso che la visita di vostra altezza volgesse al termine perché mi proponevo di celebrare l’ultimo giorno del vostro soggiorno con questo autentico piatto regale.”

Il granduca rise: “In realtà allora suppongo che avresti atteso il giorno della mia morte per trattarmi così perché non me l’hai ancora presentato. In ogni modo dovrai inventarti qualche altro favoloso piatto di commiato perché la pietanza dovrà essere sulla mia tavola domani.”

“Come piace a vostra altezza.” disse il nano e prese congedo.

Ma a LUI non piaceva per niente. Il momento del disonore sembrava imminente perché non aveva idea di come preparare la pietanza. Tornò assai triste nella propria stanza. Mentre sedeva, perso nei pensieri, l’oca Mimi, che era libera di camminare lì attorno, si avvicinò e gli chiese che cosa fosse successo. Quando sentì, disse:

“Su col morale, amico mio. Conosco assai bene questo piatto; lo avevamo spesso a casa e posso supporre piuttosto bene come sia fatto.” Allora gli disse che cosa mettervi, aggiungendo. “Penso che tutto andrà bene e se qualche bazzecola mancherà, forse non se ne accorgeranno.”

Infatti il giorno dopo un magnifico pasticcio circondato di fiori fu collocato sulla tavola. Jem stesso indossò l’abito migliore e andò in sala da pranzo. Come entrò, il capo scalco stava tagliando il pasticcio ed aiutando il duca e i suoi ospiti. Il granduca addentò un grosso boccone e sollevò gli occhi al cielo mentre lo inghiottiva.

“Oh! Si può definire la Regina dei Pasticci e nel medesimo tempo il mio nano deve essere chiamato il re dei cuochi. Non lo pensi, caro amico?”

Il principe prese vari pezzetti, li assaggiò e li esaminò attentamente poi disse con un sorriso misterioso e sarcastico:

“Il piatto è molto buono, ma la Pietanza Sovrana non è completa, come mi aspettavo.”

Il granduca si incollerì.

“Cane di un cuoco,” strillò, “come osi servirmi così? Ho giusto in mente di far saltare la tua testa come punizione.”

“Per pietà, vostra altezza, non fatelo! Ho cucinato il pasticcio in piena regola nulla è stato tralasciato. Chiedete al principe che altro avrei dovuto mettervi.”

Il principe rise. “Ero certo che non avresti cucinato questo piatto tanto bene quanto il mio cuoco, amico Naso Lungo. Sappi che ci vorrebbe un’erba detta salsa che non è conosciuta in questo paese, ma che conferisce al pasticcio il suo particolare sapore e senza la quale il tuo padrone non la gusterà mai alla perfezione.”

Il granduca s’infuriò più che mai.

“Io VOGLIO gustarlo alla perfezione.” ruggì. “O il pasticcio sarà preparato come si deve domani o la testa di questo mascalzone cadrà. Va’, birbante, ti concedo ventiquattro ore di tregua.”

Il povero nano corse nella stanza e riversò sull’oca il proprio dolore.

Lei rispose: “Se è tutto qui, allora posso aiutarti perché mio padre mi ha insegnato a riconoscere tutte le piante e tutte le erbe. Fortunatamente proprio ora c’è la luna nuova perché le erbe spuntano in questo periodo. Dimmi, ci sono castagni vicino al palazzo?”

“Oh, sì!” esclamò Naso lungo, assai sollevato, “vicino al lago, solo a duecento iarde dal palazzo, ve n’è un ampio gruppo. Perché me lo chiedi?”

“Perché l’erba cresce solo vicino alle radici dei castagni,” rispose Mimi, “non perdiamo tempo nel cercarle. Prendimi sotto il braccio e portami fuori dalle porte così io la troverò.”

Il nano fece come gli aveva detto l’oca e appena furono in giardino, la mise per terra; mentre lei s’incamminava ondeggiando più veloce che poteva verso il lago, Jem si affrettava dietro di lei con il cuore in agitazione perché sapeva che la propria vita dipendeva dal suo successo. L’oca cercò dappertutto, invano. Cercò sotto ogni castagno, rivoltando con il becco ogni filo d’erba, non si vedeva niente e la sera stava avanzando!

Improvvisamente il nano notò un vecchio e grosso albero che sorgeva solo sull’altro versante del lago. “Guarda,” gridò, “vediamo se la nostra fortuna è là.”

L’oca sbatté le ali e saltò avanti, e lui corse con la maggior velocità che le gambette gli consentissero. L’albero gettava una vasta ombra e lì sotto era quasi completamente buio, ma improvvisamente l’oca rimase immobile, sbatté le ali per la gioia e beccò qualcosa che tese all’amico sbalordito, dicendo: “Eccola e ne sta crescendo altra qui così non ti mancherà.”

Il nano fissava la pianta. Aveva un odore forte e dolce che gli rammentava i giorni dell’incantesimo. Gli steli e le foglie era di un verde bluastro e culminava con un fiore rosso scuro e brillante con il bordo giallo.

“Che prodigio!” esclamò Naso Lungo, “Credo sia proprio l’erba che mi trasformò da scoiattolo nella mia attuale e miserabile forma. Posso fare una prova?”

“Non ancora,” rispose l’oca, “Porta con te una bella manciata d’erba e andiamo nella tua stanza. Raduneremo tutto il denaro e gli abiti e allora proveremo il potere dell’erba.”

Così tornarono nella stanza di Jem e lì egli radunò i circa cinquanta ducati che aveva conservato, gli abiti e le scarpe e ne fece un fagotto. Poi affondò il viso nel mazzo d’erba e ne inalò il profumo.

Come l’ebbe fatto, tutte le membra cominciarono a scricchiolare e ad allungarsi; sentì la testa sollevarsi sulle spalle, gettò uno sguardo al naso e lo vide farsi sempre più piccolo; il petto e il dorso s’appiattirono e le gambe si allungarono.

L’oca lo guardava stupefatta. “Come sei grande e bello!” esclamò. “Grazie al cielo sei completamente trasformato.”

Jem unì le mani in segno di ringraziamento e il cuore gli si gonfiò di gratitudine. Ma la gioia non gli fece dimenticare che doveva tutto all’amica Mimi.

“Ti devo la vita e la libertà,” disse, “perché senza di te non avrei mai riacquistato il mio aspetto naturale e, anzi, ben presto sarei stato decapitato. Ti riporterò da tuo padre, che certamente conoscerà il modo per liberarti dall’incantesimo.”

L’oca accettò con gioia la sua offerta e fecero in modo di lasciare il palazzo inosservati.

Viaggiarono senza incidenti e il mago ben presto riebbe la figlia e coprì Jem di ringraziamenti e di doni di valore. Egli non perse tempo nel tornare in fretta nella città natale e i suoi genitori furono assai rapidi nel riconoscere nel giovanotto bello e ben fatto il loro figlio perduto. Con il denaro datogli dal mago aprì un negozio che fece fortuna e visse a lungo felice e contento.

Non devo dimenticare di menzionare che scompiglio provocò a palazzo l’improvvisa sparizione di Jem perché quando il giorno successivo il granduca diede ordine di decapitare il nano se non avesse trovato le erbe necessarie, il nano non fu trovato. Il principe insinuò che il duca avesse permesso al suo cuoco di scappare e quindi non avesse mantenuto la parola. La questione portò a una grande guerra tra i due principi, che fu conosciuta nella storia come la Guerra dell’Erba. Dopo molte battaglie e molte perdite di vite, alla fine fu stipulata la pace, conosciuta come la Pace del Pasticcio perché al banchetto dato in suo onore il cuoco del principe cucinò la Pietanza Sovrana e il granduca dichiarò che era del tutto eccellente.

Origine sconosciuta

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)