The Maiden with the Wooden Helmet

(MP3-08'58'')

In a little village in the country of Japan there lived long, long ago a man and his wife. For many years they were happy and prosperous, but bad times came, and at last nothing was left them but their daughter, who was as beautiful as the morning. The neighbours were very kind, and would have done anything they could to help their poor friends, but the old couple felt that since everything had changed they would rather go elsewhere, so one day they set off to bury themselves in the country, taking their daughter with them.

Now the mother and daughter had plenty to do in keeping the house clean and looking after the garden, but the man would sit for hours together gazing straight in front of him, and thinking of the riches that once were his. Each day he grew more and more wretched, till at length he took to his bed and never got up again.

His wife and daughter wept bitterly for his loss, and it was many months before they could take pleasure in anything. Then one morning the mother suddenly looked at the girl, and found that she had grown still more lovely than before. Once her heart would have been glad at the sight, but now that they two were alone in the world she feared some harm might come of it. So, like a good mother, she tried to teach her daughter all she knew, and to bring her up to be always busy, so that she would never have time to think about herself. And the girl was a good girl, and listened to all her mother’s lessons, and so the years passed away.

At last one wet spring the mother caught cold, and though in the beginning she did not pay much attention to it, she gradually grew more and more ill, and knew that she had not long to live. Then she called her daughter and told her that very soon she would be alone in the world; that she must take care of herself, as there would be no one to take care of her. And because it was more difficult for beautiful women to pass unheeded than for others, she bade her fetch a wooden helmet out of the next room, and put it on her head, and pull it low down over her brows, so that nearly the whole of her face should lie in its shadow. The girl did as she was bid, and her beauty was so hidden beneath the wooden cap, which covered up all her hair, that she might have gone through any crowd, and no one would have looked twice at her. And when she saw this the heart of the mother was at rest, and she lay back in her bed and died.

The girl wept for many days, but by-and-by she felt that, being alone in the world, she must go and get work, for she had only herself to depend upon. There was none to be got by staying where she was, so she made her clothes into a bundle, and walked over the hills till she reached the house of the man who owned the fields in that part of the country. And she took service with him and laboured for him early and late, and every night when she went to bed she was at peace, for she had not forgotten one thing that she had promised her mother; and, however hot the sun might be, she always kept the wooden helmet on her head, and the people gave her the nickname of Hatschihime.

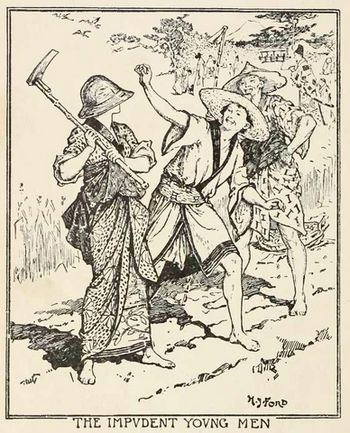

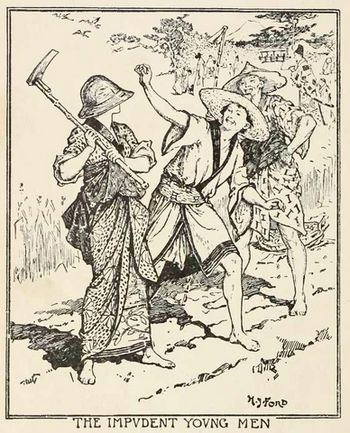

In spite, however, of all her care the fame of her beauty spread abroad: many of the impudent young men that are always to be found in the world stole softly up behind her while she was at work, and tried to lift off the wooden helmet. But the girl would have nothing to say to them, and only bade them be off; then they began to talk to her, but she never answered them, and went on with what she was doing, though her wages were low and food not very plentiful. Still she could manage to live, and that was enough

One day her master happened to pass through the field where she was working, and was struck by her industry and stopped to watch her. After a while he put one or two questions to her, and then led her into his house, and told her that henceforward her only duty should be to tend his sick wife. From this time the girl felt as if all her troubles were ended, but the worst of them was yet to come.

Not very long after Hatschihime had become maid to the sick woman, the eldest son of the house returned home from Kioto, where he had been studying all sorts of things. He was tired of the splendours of the town and its pleasures, and was glad enough to be back in the green country, among the peach-blossoms and sweet flowers. Strolling about in the early morning, he caught sight of the girl with the odd wooden helmet on her head, and immediately he went to his mother to ask who she was, and where she came from, and why she wore that strange thing over her face.

His mother answered that it was a whim, and nobody could persuade her to lay it aside; whereat the young man laughed, but kept his thoughts to himself.

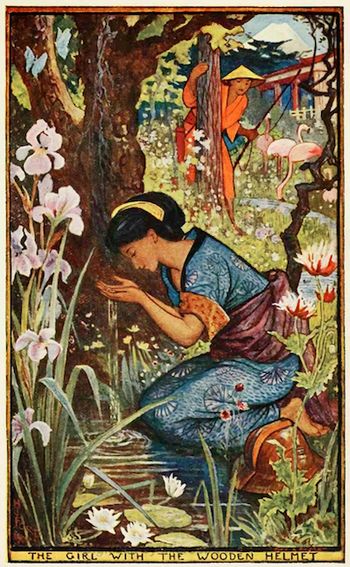

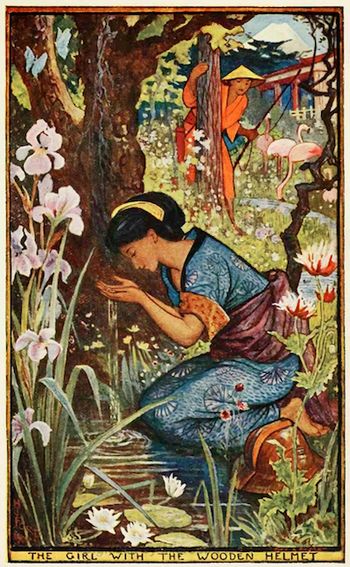

One hot day, however, he happened to be going towards home when he caught sight of his mother’s waiting maid kneeling by a little stream that flowed through the garden, splashing some water over her face. The helmet was pushed on one side, and as the youth stood watching from behind a tree he had a glimpse of the girl’s great beauty; and he determined that no one else should be his wife.

But when he told his family of his resolve to marry her they were very angry, and made up all sorts of wicked stories about her. However, they might have spared themselves the trouble, as he knew it was only idle talk. ‘I have merely to remain firm,’ thought he, ‘and they will have to give in.’ It was such a good match for the girl that it never occurred to anyone that she would refuse the young man, but so it was. It would not be right, she felt, to make a quarrel in the house, and though in secret she wept bitterly, for a long while, nothing would make her change her mind. At length one night her mother appeared to her in a dream, and bade her marry the young man. So the next time he asked her—as he did nearly every day—to his surprise and joy she consented. The parents then saw they had better make the best of a bad business, and set about making the grand preparations suitable to the occasion. Of course the neighbours said a great many ill-natured things about the wooden helmet, but the bridegroom was too happy to care, and only laughed at them.

When everything was ready for the feast, and the bride was dressed in the most beautiful embroidered dress to be found in Japan, the maids took hold of the helmet to lift it off her head, so that they might do her hair in the latest fashion. But the helmet would not come, and the harder they pulled, the faster it seemed to be, till the poor girl yelled with pain. Hearing her cries the bridegroom ran in and soothed her, and declared that she should be married in the helmet, as she could not be married without. Then the ceremonies began, and the bridal pair sat together, and the cup of wine was brought them, out of which they had to drink. And when they had drunk it all, and the cup was empty, a wonderful thing happened. The helmet suddenly burst with a loud noise, and fell in pieces on the ground; and as they all turned to look they found the floor covered with precious stones which had fallen out of it. But the guests were less astonished at the brilliancy of the diamonds than at the beauty of the bride, which was beyond anything they had ever seen or heard of. The night was passed in singing and dancing, and then the bride and bridegroom went to their own house, where they lived till they died, and had many children, who were famous throughout Japan for their goodness and beauty.

Japanische Marchen.

La ragazza con il casco di legno

Tanto tanto tempo fa in un piccolo villaggio in Giappone vivevano un uomo e sua moglie. Per molti anni erano stati felici e avevano prosperato poi era venuti tempi duri e non era rimasto loro niente altro che la figlia, bella come il mattino. I vicini erano assai cortesi e avrebbero fatto qualsiasi cosa in loro potere per aiutare i poveri amici, ma la vecchia coppia sentiva di doversene andare altrove sin da quando le loro sorti erano mutate, così un giorno partirono per nascondersi in campagna e portarono con loro la figlia.

Dovete sapere che madre e figlia erano molto occupate a tenere pulita la casa e a curare il giardino, ma l’uomo sedeva per ore per ore a guardare davanti a sé a pensare quanto fosse stato ricco un tempo. Ogni giorno diventava sempre più magro finché infine si mise a letto e non si alzò più.

La moglie e la figlia piansero amaramente la sua perdita e ci vollero molti mesi prima che traessero piacere da qualcosa. Poi una mattina la madre guardò improvvisamente la ragazza e vide che era cresciuta diventando persino più bella di prima. Una volta il suo cuore avrebbe esultato a quella vista, ma adesso che erano rimaste sole al mondo, temeva potesse accaderle qualcosa di male. Così, da brava madre, tentò di insegnare alla figlia tutto ciò che sapeva e di fare in modo che fosse sempre occupata così che non avesse mai tempo per pensare a se stessa. La ragazza era brava e ascoltava tutte le lezioni della madre e così trascorsero gli anni.

Infine in una primavera piovosa la madre prese freddo e, sebbene in principio non vi badasse molto, pian piano si ammalò sempre di più e capì che non sarebbe vissuta a lungo. Allora chiamò la figlia e le disse che molto presto sarebbe rimasta sola al mondo, che doveva avere cura di sé perché nessun altro avrebbe potuto farlo. E siccome per le donne belle era più difficile passare inosservate che per le altre, le disse di andare a prendere il casco di legno nell’altra stanza e di metterselo in testa, abbassandolo sulla fronte così che la maggior parte del suo viso restasse in ombra. La ragazza fece come le era stato detto e la sua bellezza rimase nascosta sotto il casco di legno che le copriva completamente i capelli, così che avrebbe potuto attraversare qualsiasi folla e nessuno l’avrebbe guardata due volte. Quando la donna vide ciò, il suo cuore di madre si arrestò e si sdraiò nel letto e morì.

La ragazza pianse per molti giorni ma pian piano si rese conto che, essendo rimasta sola al mondo, doveva andare a procurarsi un lavoro perché ora dipendeva solo da se stessa. Non ne avrebbe ricavato nulla restando nel posto in cui era così mise i vestiti in un fagotto e oltrepassò le colline finché giunse alla casa di un uomo che lavorava i campi in quella parte del paese. Si mise al suo servizio e lavorava per lui dalla mattina alla sera e ogni notte, quando andava a letto, era in pace con se stessa perché non aveva dimenticato nulla di ciò che aveva promesso alla madre; e in ogni modo, per quanto il sole potesse essere caldo, indossava sempre il casco di legno e la gente l’aveva soprannominata Hatschihime.

Malgrado tutta la sua attenzione, la fama della sua bellezza si diffuse; molti giovani impudenti, come sempre se ne trovano al mondo, le si avvicinavano in punta di piedi mentre lavorava e tentavano di toglierle il casco di legno. Ma la ragazza non aveva nulla da dire loro se non di andarsene allora incominciavano a parlarle, ma lei non rispondeva mai e continuava a fare ciò che stava facendo, sebbene il suo salario fosse scarso e il cibo non molto abbondante. Riusciva a tirare avanti e le bastava.

Un giorno al suo padrone capitò di passare mentre lei stava lavorando e fu dalla sua operosità così si fermò a guardarla. Dopo un po’ le rivolse una o due domande, poi la condusse in casa e le disse che da quel momento in poi il suo unico compito sarebbe stato quello di accudire la sua moglie malata. A questo punto la ragazza pensò che tutti i suoi problemi fossero finiti, ma il peggio doveva ancora venire.

Non molto tempo dopo che Hatschihime aveva incominciato ad accudire la donna malata, il figlio maggiore tornò a casa da Kyoto, dove aveva studiato ogni genere di cose. Era stanco delle bellezze della città e dei suoi divertimenti e gli faceva piacere tornare nel suo verde paese tra i fiori di pesco e i dolci fiori. Passeggiando una mattina presto, intravide la ragazza con l’insolito casco di legno sulla testa e immediatamente andò dalla madre a chiedere chi fosse, da dove venisse e perché indossasse quella strana cosa a coprire il volto.

La madre gli rispose che era un capriccio e che nessuno poteva convincerla a toglierselo; al che il giovane rise, ma tenne per sé i propri pensieri.

In una calda giornata capitò che stesse andando verso casa quando scorse la cameriera di sua madre inginocchiata sul ruscello che scorreva nel giardino mentre si sciacquava il viso. Il casco era posato da una parte e, siccome il ragazzo stava guardando da dietro un albero, vide di sfuggita la grande bellezza della ragazza e decise che nessun’altra sarebbe stata sua moglie.

Quando annunciò ai genitori la propria decisione di sposarla, essi si arrabbiarono molto e gli dissero ogni sorta di cattiverie su di lei. Tuttavia avrebbero potuto risparmiarsi la fatica perché lui sapeva come fossero solo chiacchiere oziose. “Devo solo restare irremovibile” pensò il ragazzo “e dovranno cedere.” Era un’occasione così buona per la ragazza che a nessuno sarebbe venuto in mente che potesse rifiutare il giovane, ma così fu. Sentiva che non sarebbe stato giusto creare un dissidio in casa e, sebbene in segreto piangesse amaramente, per un bel po’ nulla poté farle cambiare idea. Infine una notte le apparve in sogno la madre e le ordinò di sposare il giovane. Così la volta seguente in cui lui glielo chiese – come faceva quasi ogni giorno – con sue grandi sorpresa e gioia lei acconsentì. I genitori compresero che sarebbe stato meglio fare buon viso a cattivo gioco e si diedero ai grandi preparativi necessari per l’occasione. Naturalmente i vicini dissero una gran quantità di malignità sul casco di legno, ma il promesso sposo era troppo felice per curarsene e si limitava a riderne.

Quando tutto fu pronto per la festa e la sposa ebbe indossato il più bel vestito ricamato di tutto il Giappone, le cameriere le tolsero il casco dalla testa in modo da poterle acconciare i capelli nella maniera più alla moda. Ma il casco non veniva via e più tiravano, più sembrava saldo finché la povera ragazza gridò di dolore. Sentendo le sue grida, il promesso sposo corse in casa e la tranquillizzò, dichiarando che si sarebbe sposata con il casco, se non poteva farlo senza. Allora cominciò la cerimonia, la coppia di sposi sedette vicina, furono portate le coppe di vino dalle quali dovevano bere. Quando ebbero bevuto tutto e le coppe furono vuote, accadde una cosa meravigliosa. Il casco si ruppe con gran rumore a cadde a terra in pezzi; siccome si voltarono tutti a guardare, videro il pavimento coperto di pietre preziose che ne erano cadute fuori. Ma gli ospiti furono meno stupefatti dallo splendore dei diamanti che dalla bellezza della sposa, la quale andava oltre qualsiasi cosa avessero visto o sentito. La notte trascorse tra canti e danze e poi lo sposo e la sposa andarono nella loro casa, in cui vissero fino alla morte, ed ebbero molti figli che divennero famosi in tutto il Giappone per bontà e bellezza.

Fiaba giapponese.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)