Virgilius the Sorcerer

(MP3-21'38'')

Long, long ago there was born to a Roman knight and his wife Maja a little boy called Virgilius. While he was still quite little, his father died, and the kinsmen, instead of being a help and protection to the child and his mother, robbed them of their lands and money, and the widow, fearing that they might take the boy’s life also, sent him away to Spain, that he might study in the great University of Toledo.

Virgilius was fond of books, and pored over them all day long. But one afternoon, when the boys were given a holiday, he took a long walk, and found himself in a place where he had never been before. In front of him was a cave, and, as no boy ever sees a cave without entering it, he went in. The cave was so deep that it seemed to Virgilius as if it must run far into the heart of the mountain, and he thought he would like to see if it came out anywhere on the other side. For some time he walked on in pitch darkness, but he went steadily on, and by-and-by a glimmer of light shot across the floor, and he heard a voice calling, ‘Virgilius! Virgilius!’

‘Who calls?’ he asked, stopping and looking round.

‘Virgilius!’ answered the voice, ‘do you mark upon the ground where you are standing a slide or bolt?’

‘I do,’ replied Virgilius.

‘Then,’ said the voice, ‘draw back that bolt, and set me free.’

‘But who are you?’ asked Virgilius, who never did anything in a hurry.

‘I am an evil spirit,’ said the voice, ‘shut up here till Doomsday, unless a man sets me free. If you will let me out I will give you some magic books, which will make you wiser than any other man.’

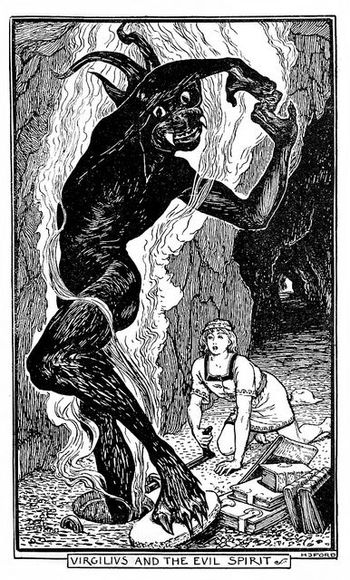

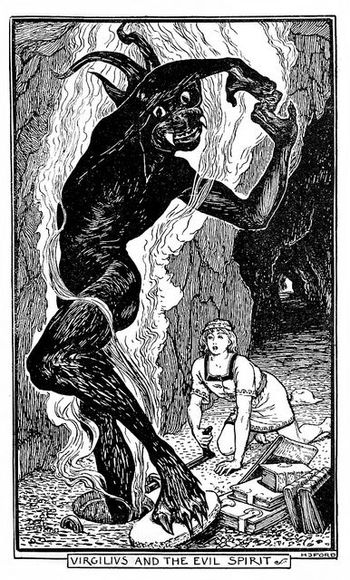

Now Virgilius loved wisdom, and was tempted by these promises, but again his prudence came to his aid, and he demanded that the books should be handed over to him first, and that he should be told how to use them. The evil spirit, unable to help itself, did as Virgilius bade him, and then the bolt was drawn back. Underneath was a small hole, and out of this the evil spirit gradually wriggled himself; but it took some time, for when at last he stood upon the ground he proved to be about three times as large as Virgilius himself, and coal black besides.

‘Why, you can’t have been as big as that when you were in the hole!’ cried Virgilius.

‘But I was!’ replied the spirit.

‘I don’t believe it!’ answered Virgilius.

‘Well, I’ll just get in and show you,’ said the spirit, and after turning and twisting, and curling himself up, then he lay neatly packed into the hole. Then Virgilius drew the bolt, and, picking the books up under his arm, he left the cave.

For the next few weeks Virgilius hardly ate or slept, so busy was he in learning the magic the books contained. But at the end of that time a messenger from his mother arrived in Toledo, begging him to come at once to Rome, as she had been ill, and could look after their affairs no longer.

Though sorry to leave Toledo, where he was much thought of as showing promise of great learning, Virgilius would willingly have set out at once, but there were many things he had first to see to. So he entrusted to the messenger four pack-horses laden with precious things, and a white palfrey on which she was to ride out every day. Then he set about his own preparations, and, followed by a large train of scholars, he at length started for Rome, from which he had been absent twelve years.

His mother welcomed him back with tears in her eyes, and his poor kinsmen pressed round him, but the rich ones kept away, for they feared that they would no longer be able to rob their kinsman as they had done for many years past. Of course, Virgilius paid no attention to this behaviour, though he noticed they looked with envy on the rich presents he bestowed on the poorer relations and on anyone who had been kind to his mother.

Soon after this had happened the season of tax-gathering came round, and everyone who owned land was bound to present himself before the emperor. Like the rest, Virgilius went to court, and demanded justice from the emperor against the men who had robbed him. But as these were kinsmen to the emperor he gained nothing, as the emperor told him he would think over the matter for the next four years, and then give judgment. This reply naturally did not satisfy Virgilius, and, turning on his heel, he went back to his own home, and, gathering in his harvest, he stored it up in his various houses.

When the enemies of Virgilius heard of this, they assembled together and laid siege to his castle. But Virgilius was a match for them. Coming forth from the castle so as to meet them face to face, he cast a spell over them of such power that they could not move, and then bade them defiance. After which he lifted the spell, and the invading army slunk back to Rome, and reported what Virgilius had said to the emperor.

Now the emperor was accustomed to have his lightest word obeyed, almost before it was uttered, and he hardly knew how to believe his ears. But he got together another army, and marched straight off to the castle. But directly they took up their position Virgilius girded them about with a great river, so that they could neither move hand nor foot, then, hailing the emperor, he offered him peace, and asked for his friendship. The emperor, however, was too angry to listen to anything, so Virgilius, whose patience was exhausted, feasted his own followers in the presence of the starving host, who could not stir hand or foot.

Things seemed getting desperate, when a magician arrived in the camp and offered to sell his services to the emperor. His proposals were gladly accepted, and in a moment the whole of the garrison sank down as if they were dead, and Virgilius himself had much ado to keep awake. He did not know how to fight the magician, but with a great effort struggled to open his Black Book, which told him what spells to use. In an instant all his foes seemed turned to stone, and where each man was there he stayed. Some were half way up the ladders, some had one foot over the wall, but wherever they might chance to be there every man remained, even the emperor and his sorcerer. All day they stayed there like flies upon the wall, but during the night Virgilius stole softly to the emperor, and offered him his freedom, as long as he would do him justice. The emperor, who by this time was thoroughly frightened, said he would agree to anything Virgilius desired. So Virgilius took off his spells, and, after feasting the army and bestowing on every man a gift, bade them return to Rome. And more than that, he built a square tower for the emperor, and in each corner all that was said in that quarter of the city might be heard, while if you stood in the centre every whisper throughout Rome would reach your ears.

Having settled his affairs with the emperor and his enemies, Virgilius had time to think of other things, and his first act was to fall in love! The lady’s name was Febilla, and her family was noble, and her face fairer than any in Rome, but she only mocked Virgilius, and was always playing tricks upon him. To this end, she bade him one day come to visit her in the tower where she lived, promising to let down a basket to draw him up as far as the roof. Virgilius was enchanted at this quite unexpected favour, and stepped with glee into the basket. It was drawn up very slowly, and by-and-by came altogether to a standstill, while from above rang the voice of Febilla crying, ‘Rogue of a sorcerer, there shalt thou hang!’ And there he hung over the market-place, which was soon thronged with people, who made fun of him till he was mad with rage. At last the emperor, hearing of his plight, commanded Febilla to release him, and Virgilius went home vowing vengeance.

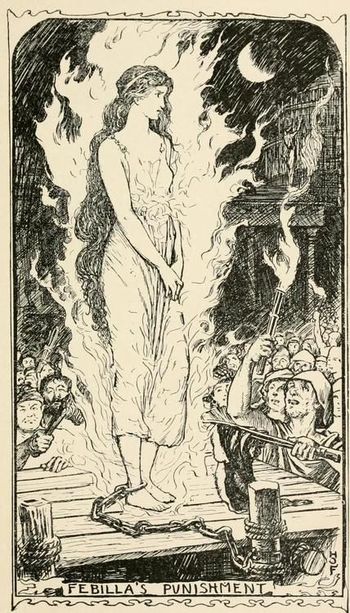

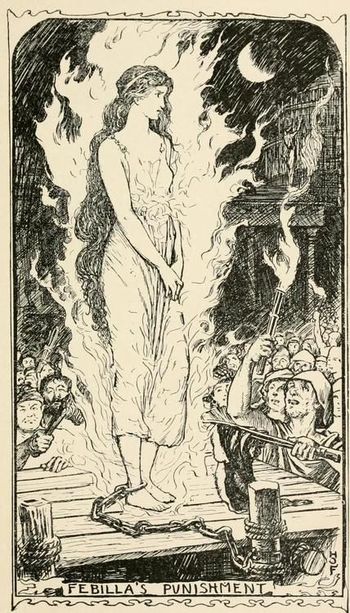

The next morning every fire in Rome went out, and as there were no matches in those days this was a very serious matter. The emperor, guessing that this was the work of Virgilius, besought him to break the spell. Then Virgilius ordered a scaffold to be erected in the market-place, and Febilla to be brought clothed in a single white garment. And further, he bade every one to snatch fire from the maiden, and to suffer no neighbour to kindle it. And when the maiden appeared, clad in her white smock, flames of fire curled about her, and the Romans brought some torches, and some straw, and some shavings, and fires were kindled in Rome again.

For three days she stood there, till every hearth in Rome was alight, and then she was suffered to go where she would.

But the emperor was wroth at the vengeance of Virgilius, and threw him into prison, vowing that he should be put to death. And when everything was ready he was led out to the Viminal Hill, where he was to die.

He went quietly with his guards, but the day was hot, and on reaching his place of execution he begged for some water. A pail was brought, and he, crying ‘Emperor, all hail! seek for me in Sicily,’ jumped headlong into the pail, and vanished from their sight.

For some time we hear no more of Virgilius, or how he made his peace with the emperor, but the next event in his history was his being sent for to the palace to give the emperor advice how to guard Rome from foes within as well as foes without. Virgilius spent many days in deep thought, and at length invented a plan which was known to all as the ‘Preservation of Rome.’

On the roof of the Capitol, which was the most famous public building in the city, he set up statues representing the gods worshipped by every nation subject to Rome, and in the middle stood the god of Rome herself. Each of the conquered gods held in its hand a bell, and if there was even a thought of treason in any of the countries its god turned its back upon the god of Rome and rang its bell furiously, and the senators came hurrying to see who was rebelling against the majesty of the empire. Then they made ready their armies, and marched against the foe.

Now there was a country which had long felt bitter jealousy of Rome, and was anxious for some way of bringing about its destruction. So the people chose three men who could be trusted, and, loading them with money, sent them to Rome, bidding them to pretend that they were diviners of dreams. No sooner had the messengers reached the city than they stole out at night and buried a pot of gold far down in the earth, and let down another into the bed of the Tiber, just where a bridge spans the river.

Next day they went to the senate house, where the laws were made, and, bowing low, they said, ‘Oh, noble lords, last night we dreamed that beneath the foot of a hill there lies buried a pot of gold. Have we your leave to dig for it?’ And leave having been given, the messengers took workmen and dug up the gold and made merry with it.

A few days later the diviners again appeared before the senate, and said, ‘Oh, noble lords, grant us leave to seek out another treasure, which has been revealed to us in a dream as lying under the bridge over the river.’

And the senators gave leave, and the messengers hired boats and men, and let down ropes with hooks, and at length drew up the pot of gold, some of which they gave as presents to the senators.

A week or two passed by, and once more they appeared in the senate house.

‘O, noble lords!’ said they, ‘last night in a vision we beheld twelve casks of gold lying under the foundation stone of the Capitol, on which stands the statue of the Preservation of Rome. Now, seeing that by your goodness we have been greatly enriched by our former dreams, we wish, in gratitude, to bestow this third treasure on you for your own profit; so give us workers, and we will begin to dig without delay.’

And receiving permission they began to dig, and when the messengers had almost undermined the Capitol they stole away as secretly as they had come.

And next morning the stone gave way, and the sacred statue fell on its face and was broken. And the senators knew that their greed had been their ruin.

From that day things went from bad to worse, and every morning crowds presented themselves before the emperor, complaining of the robberies, murders, and other crimes that were committed nightly in the streets.

The emperor, desiring nothing so much as the safety of his subjects, took counsel with Virgilius how this violence could be put down.

Virgilius thought hard for a long time, and then he spoke:

‘Great prince,’ said he, ‘cause a copper horse and rider to be made, and stationed in front of the Capitol. Then make a proclamation that at ten o’clock a bell will toll, and every man is to enter his house, and not leave it again.’

The emperor did as Virgilius advised, but thieves and murderers laughed at the horse, and went about their misdeeds as usual.

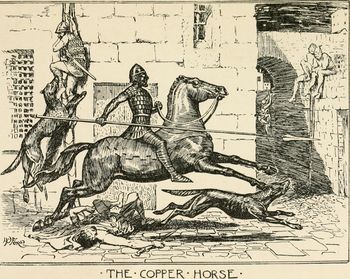

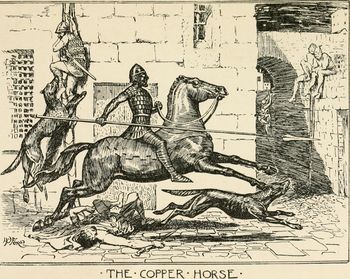

But at the last stroke of the bell the horse set off at full gallop through the streets of Rome, and by daylight men counted over two hundred corpses that it had trodden down. The rest of the thieves—and there were still many remaining—instead of being frightened into honesty, as Virgilius had hoped, prepared rope ladders with hooks to them, and when they heard the sound of the horse’s hoofs they stuck their ladders into the walls, and climbed up above the reach of the horse and its rider.

Then the emperor commanded two copper dogs to be made that would run after the horse, and when the thieves, hanging from the walls, mocked and jeered at Virgilius and the emperor, the dogs leaped high after them and pulled them to the ground, and bit them to death.

Thus did Virgilius restore peace and order to the city.

Now about this time there came to be noised abroad the fame of the daughter of the sultan who ruled over the province of Babylon, and indeed she was said to be the most beautiful princess in the world.

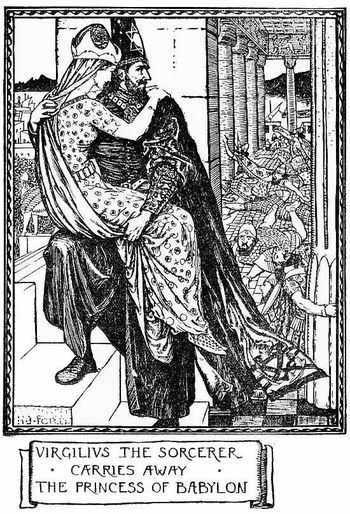

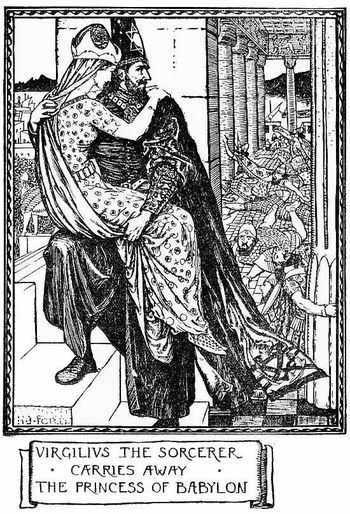

Virgilius, like the rest, listened to the stories that were told of her, and fell so violently in love with all he heard that he built a bridge in the air, which stretched all the way between Rome and Babylon. He then passed over it to visit the princess, who, though somewhat surprised to see him, gave him welcome, and after some conversation became in her turn anxious to see the distant country where this stranger lived, and he promised that he would carry her there himself, without wetting the soles of his feet.

The princess spent some days in the palace of Virgilius, looking at wonders of which she had never dreamed, though she declined to accept the presents he longed to heap on her. The hours passed as if they were minutes, till the princess said that she could be no longer absent from her father. Then Virgilius conducted her himself over the airy bridge, and laid her gently down on her own bed, where she was found next morning by her father.

She told him all that had happened to her, and he pretended to be very much interested, and begged that the next time Virgilius came he might be introduced to him.

Soon after, the sultan received a message from his daughter that the stranger was there, and he commanded that a feast should be made ready, and, sending for the princess delivered into her hands a cup, which he said she was to present to Virgilius herself, in order to do him honour.

When they were all seated at the feast the princess rose and presented the cup to Virgilius, who directly he had drunk fell into a deep sleep.

Then the sultan ordered his guards to bind him, and left him there till the following day.

Directly the sultan was up he summoned his lords and nobles into his great hall, and commanded that the cords which bound Virgilius should be taken off, and the prisoner brought before him. The moment he appeared the sultan’s passion broke forth, and he accused his captive of the crime of conveying the princess into distant lands without his leave.

Virgilius replied that if he had taken her away he had also brought her back, when he might have kept her, and that if they would set him free to return to his own land he would come hither no more.

‘Not so!’ cried the sultan, ‘but a shameful death you shall die!’ And the princess fell on her knees, and begged she might die with him.

‘You are out in your reckoning, Sir Sultan!’ said Virgilius, whose patience was at an end, and he cast a spell over the sultan and his lords, so that they believed that the great river of Babylon was flowing through the hall, and that they must swim for their lives. So, leaving them to plunge and leap like frogs and fishes, Virgilius took the princess in his arms, and carried her over the airy bridge back to Rome.

Now Virgilius did not think that either his palace, or even Rome itself, was good enough to contain such a pearl as the princess, so he built her a city whose foundations stood upon eggs, buried far away down in the depths of the sea. And in the city was a square tower, and on the roof of the tower was a rod of iron, and across the rod he laid a bottle, and on the bottle he placed an egg, and from the egg there hung chained an apple, which hangs there to this day. And when the egg shakes the city quakes, and when the egg shall be broken the city shall be destroyed. And the city Virgilius filled full of wonders, such as never were seen before, and he called its name Naples.

Adapted from ‘Virgilius the Sorcerer.’ Unknown, Europe.

Virgilius lo stregone

Tanto tanto tempo fa a a un cavaliere romano e a sua moglie Maja nache un bambino che fu chiamato Virgilius. Quando era ancora molto piccolo, il padre morì e i parenti, invece di dare aiuto e protezione al bambino e alla madre, li derubarono delle terre e del denaro e la vedova, temendo che potessero anche uccidere il bambino, lo mandò in Spagna perché potesse studiare alla grande università di Toledo.

Virgilius amava i libri e vi si dedicava tutto il giorno. Un pomeriggio in cui il ragazzo si era preso un giorno di vacanza, fece una lunga passeggiata e si ritrovò in un luogo in cui non era mai stato prima. Di fronte a lui c’era una caverna e siccome nessun bambino vede una caverna senza entrarvi, entrò. La caverna era così profonda che a Virgilius sembrò di dover arrivare fino al cuore della montagna e pensò che gli sarebbe piaciuto vedere le lo avrebbe condotto da qualche parte sull’altro lato. Per un po’ di tempo camminò nelle tenebre più fitte, ma procedeva con regolarità, e di lì a poco un barlume di luce filtrò attraverso il pavimento e sentì una voce che chiamava: “Virgilius! Virgilius!”

“Chi chiama?” chiese, fermandosi e e guardandosi attorno.

“Virgilius!” rispose la voce “Vedi una lastra o un chiavistello sul pavimento nel punto in cui ti trovi?””Lo vedo.” rispose Virgilius.

La voce disse: “Allora togli il chiavistello e liberami.”

“Chi sei?” chiese Virgilius, che non faceva mai nulla frettolosamente.

“Sono uno spirito maligno” disse la voce “imprigionato qui sotto fino al Giorno del Giudizio, a meno che un uomo mi liberi. Se lo farai, ti darò dei libri di magia che faranno di te il più sapiente degli uomini.”

Virgilius amava la sapienza e fu tentato da questa promessa, ma la prudenza gli venne in aiuto e chiese che prima gli venissero consegnati i libri e gli venisse detto come usarli. Lo spirito maligno, non potendosi aiutare da solo, fece come gli aveva detto Virgilius e allora il chiavistello fu tolto. Sotto c’era un piccolo buco e da esso gradualmente uscì contorcendosi lo spirito maligno; gli ci volle un po’ di tempo e quando alla fine fu sul terreno, si rivelò essere tre volte più grande di Virgilius stesso e per di più nero come il carbone.

“Suvvia, non potevi essere grande così mentre eri nel buco!” esclamò Virgilius.

“Sì che lo ero!” rispose lo spirito.

“Non ci credo!” ribatté Virgilius.

“Va bene, tornerò dentro e te lo dimostrerò.” disse lo spirito, e allora girandosi, torcendosi e avvolgendosi su se stesso fu di nuovo abilmente compresso nel buco. Allora Virgilius chiuse il chiavistello e, prendendo i libri sotto il braccio, lasciò la caverna.

Nelle settimane successive Vigilius mangiò e dormi a malapena, troppo occupato a imparare la magia contenuta nei libri. Ma al termine di quel periodo giunse a Toledo un messaggero inviato da sua madre che lo pregò di tornare subito a Roma perché lei era malata e non poteva curarsi dei loro affari ancora per molto.

Sebbene dispiaciuto di lasciare Toledo, dove ancora molto gli prometteva un ricco apprendimento, Virgilius sarebbe partito volentieri subito, ma c’erano molte cose che prima doveva fare. Così affidò al messaggero quattro cavalli carichi di cose preziose e un cavallo da sella bianco sul quale lei potesse cavalcare ogni giorno. Poi si dedicò ai preparativi e, seguito da un lungo corteo di studenti, alla fine partì per Roma, dalla quale mancava da dodici anni.

La madre salutò il suo ritorno con le lacrime agli occhi e i parenti poveri lo circondarono, mentre quelli ricchi gli stettero alla larga perché temevano che non ci sarebbero più stati in grado di derubarlo come avevano fatto molti anni prima. Naturalmente Virgilius non badò a questo comportamento, sebbene avesse notato che si mostravano invidiosi dei ricchi doni che aveva fatto ai parenti più poveri e a chiunque fosse stato gentile con sua madre.

Poco dopo venne il momento di pagare le tasse e chiunque possedesse della terra era tenuto a presentarsi davanti all’imperatore. Come gli altri Virgilius andò a corte e chiese giustizia all’imperatore contro gli uomini che lo avevano derubato. Siccome erano parenti dell’imperatore, non ottenne nulla in quanto egli gli disse che ci avrebbe riflettuto sulla questione per i prossimi quattro anni e poi avrebbe giudicato. Questa risposta naturalmente non soddisfece Virgilius il quale girò i tacchi e tornò a casa e, radunando tutto il raccolto, lo immagazzinò nelle sue varie case.

Quando i nemici di Virgilio lo seppero, si riunirono e assediarono al suo castello, ma Virgilius e tenne loro testa. Uscendo dal castello per incontrarli a faccia a faccia, gettò su di loro un incantesimo di un tale potere che essi non poterono muoversi e poi annunciò loro la sfida. Dopo di che sciolse l’incantesimo e l’esercito invasore se la svignò verso Roma e riferì all’imperatore le parole di Virgilius.

L’imperatore era abituato a essere obbedito alla minima parola, quasi prima di pronunciarla, e a malapena credette alle proprie orecchie. Radunò un altro esercito e marciò verso il castello. Ma appena presero posizione, Virgilius li circondò con un grande fiume così che non poterono muovere né mani né piedi, poi, salutando l’imperatore, gli offrì la pace e chiese la sua amicizia. Tuttavia l’imperatore era troppo arrabbiato per ascoltare qualsiasi cosa così Virgilius, la cui pazienza si era esaurita, banchettò con i propri seguaci davanti agli assedianti affamati, che non potevano muovere una mano un piede.

La situazione sembrava disperata quando giunse all’accampamento un mago e si offrì di vendere i propri servigi all’imperatore. La sua proposta fu accettata molto volentieri e in un attimo l’intera guarnigione cadde a terra come morta e Virgilius stesso fece una gran fatica a restare sveglio. Non sapeva come combattere il mago, ma con un grande sforzo lottò per aprire il Libro Nero che gli disse quale incantesimo usare. In un istante tutti i suoi nemici sembrarono tramutati in pietra e ogni uomo rimase dove si trovava. Alcuni a metà sulle scale, altri con un piede sul muro, ma qualsiasi cosa stessero tentando di fare, rimasero lì, persino l’imperatore e il suo mago. Per tutto il giorno rimasero lì come mosche sul muro, ma durante la notte Virgilius andò di soppiatto dall’imperatore e gli offri la libertà a condizione che gli rendesse giustizia. l’imperatore, che stavolta era completamente spaventato, rispose che avrebbe acconsentito a ogni cosa Virgilius desiderasse. Così Virgilius sciolse l’incantesimo e dopo aver intrattenuto a banchetto l’esercito e dato un dono a ogni uomo, disse loro di tornare a Roma. E inoltre costruì una torre quadrata per l’imperatore e in ogni angolo si poteva udire tutto ciò che veniva detto in quel quartiere della città mentre se si stava al centro, giungeva all’orecchio ogni sussurro che attraversasse Roma.

Sistemati gli affari con l’imperatore e con i nemici, Virgilius ebbe il tempo di pensare ad altre cose e la prima cosa che fece fu innamorarsi! Il nome della dama era Febilla, la sua famiglia era nobile e il suo viso il più bello di qualsiasi altro a Roma, ma scherniva Virgilius e gli giocava sempre degli scherzi. Alla fine un giorno gli ordinò di farle visita nella torre in cui viveva, promettendo di calare un cesto con il quale farlo salire fino al soffitto. Virgilius fu conquistato da questo inatteso favore ed entrò contento nel canestro. Fu sollevato assai lentamente e di lì a poco giunse a un punto da cui scaturì la voce di Febilla che esclamava: “Canaglia di uno stregone, resterai appeso lì!” e li rimase appeso sopra la piazza del mercato, che ben presto si riempì di gente che si prese gioco di lui finché fu pazzo di collera. Alla fine l’imperatore, venendo a sapere della sua situazione, ordino a Febilla di lasciarlo andare e Virgilus tornò a casa giurando vendetta.

Il mattino seguente ogni fuoco a Roma era spento e siccome a quel tempo non esistevano i fiammiferi, era una faccenda molto seria. L’imperatore, intuendo che fosse opera di Virgilius, lo supplicò di spezzare l’incantesimo. Allora Virgilius ordinò che fosse eretto un patibolo nella piazza del mercato e che vi fosse condotta Febilla vestita con un semplice abito bianco. Inoltre ognuno doveva accendere il fuoco dalla fanciulla e non permettere che il vicino lo accendesse. Quando la ragazza comparve, avvolta nella tunica bianca, le fiamme l’avvolsero e i romani portarono alcune torce,

un po’ di paglia e un po’ di trucioli e a Roma furono di nuovo accesi i fuochi.

Rimase lì per tre giorni finché ogni caminetto di Roma fu acceso e poi le fu permesso di andare dove volesse.

L’imperatore fu sdegnato dalla vendetta di Virgilius e lo gettò in prigione, giurando che l’avrebbe messo a morte. Quando tutto fu pronto, fu condotto sul colle Viminale sul quale doveva morire.

Andò tranquillamente con le guardie, ma la giornata era calda e mentre raggiungevano il luogo dell’esecuzione, pregò di avere un po’ d’acqua. Gliene fu portata un secchio e lui, gridando: “Ave, Imperatore! Cercami in Sicilia.” balzò nel secchio e sparì alla loro vista.

Per un po’ di tempo non si sentì parlare di Virgilius o di come avesse fatto pace con l’imperatore, l’evento successivo di questa storia fu la sua chiamata al palazzo dell’imperatore per consigliarlo su come difendere Roma tanto dai nemici interni quanto da quelli esterni. Virgilius trascorse molti giorni immerso in profonde riflessioni e alla fine elaborò un piano che fu conosciuto da tutti come “Conservazione di Roma.”

Sul tetto del Campidoglio, che era il palazzo pubblico più famoso della città, fece collocare statue che rappresentavano gli dei adorati da ogni nazione soggetta a Roma e in mezzo c’era il dio stesso di Roma. Ognuno degli dei conquistati aveva in mano una campana e se c’era anche un solo pensiero di tradimento in uno dei paesi, il suo dio volgeva le spalle al dio di Roma e suonava furiosamente la campana, così i senatori si affrettavano a vedere chi si stesse ribellando contro la maestà dell’impero. Allora preparavano l’esercito e marciavano contro il nemico.

C’era un paese che da lungo tempo nutriva un’amara gelosia nei confronti di Roma ed era ansioso di arrivare in qualche modo a distruggerla. Così il popolo scelse tre uomini dei quali si poteva fidare e, fornendoli di denaro, li mandò a Roma, dicendolo loro di fingere che fossero indovini di sogni. I messaggeri avevano appena raggiunto la città che una notte rubarono e seppellirono una pentola d’oro bene in profondità nella terra e un’altra la deposero nel letto del Tevere, proprio dove un ponte attraversava il fiume.

Il giorno seguente si recarono in Senato, in cui venivano emanate le leggi, e inchinandosi profondamente, dissero: “Nobili signori, la scorsa notte abbiamo sognato che ai piedi di una collina giace una pentola d’oro. Abbiamo il vostro permesso di scavare?” e avendo ottenuto il permesso, i messaggeri presero degli operai, estrassero l’oro e li fecero felici con esso.

Pochi giorni dopo gli indovini comparvero di nuovo in Senato e dissero: “Nobili signori, dateci il permesso di cercare un altro tesoro, che si è rivelato a noi in sogno giacere sotto il ponte sul fiume.”

I senatori diedero il permesso e i messaggeri noleggiarono barche e uomini, calarono una fune con un gancio e alla fine tirarono su la pentola con l’oro, di una parte del quale fecero dono ai senatori.

Trascorsero una o due settimane e di nuovo comparvero in Senato.

“Nobili signori,” dissero “la scorsa notte una visione ci ha mostrato dodici barili d’oro che giacciono sotto la pietra del Campidoglio sulla quale è poggiata la stata della Conservazione di Roma. Dato che per la vostra bontà ci siamo grandemente arricchiti con i nostri precedenti sogni, desideriamo, in segno di gratitudine, offrirvi questo terzo tesoro per vostro profitto, perciò dateci degli operai e cominceremo lo scavo senza indugio.”

Ricevendo il permesso, cominciarono a scavare e quando i messaggeri ebbero quasi scalzato il Campidoglio, se ne andarono in segreto come erano venuti. I senatori capirono che la loro avidità era stata la loro rovina.

Da quel giorno le cose andarono di male in peggio e ogni mattina la folla si presentava davanti all’imperatore, reclamando per i furti, gli omicidi e gli altri crimini che venivano commessi di notte nelle strade.

L’imperatore, non desiderando altro quanto la sicurezza dei sudditi, consultò Virgilius su come stroncare quella violenza.

Virgilio vi pensò a lungo e poi disse:

“Grande principe,” devono essere fabbricati un cavaliere e un cavallo di rame e collocati di fronte al Campidoglio. Poi emanerete un proclama in cui direte che alle dieci in punto una campana rintoccherà e ogni uomo dovrà entrare in casa e non uscirne di nuovo.”

L’imperatore seguì il consiglio di Virgilius, ma ladri e assassini risero del cavallo e continuarono a compiere i loro misfatti come il solito.

Ma all’ultimo rintocco della campana il cavallo partì al galoppo per le strade di Roma e alla luce del sole gli uomini contarono oltre duecento corpi che aveva calpestato. I ladri rimasti – e ce n’erano ancora molti – invece di essere indotti all’onestà dalla paura, come Virgilius aveva sperato, prepararono funi con ganci e quando sentirono il rumore degli zoccoli del cavallo, appoggiarono le scale al muro e si arrampicarono fuori della portata del cavallo e del suo cavaliere.

Allora l’imperatore ordinò che fossero costruiti due cani di rame che corressero davanti al cavallo e quando i ladri, appesi ai muri, canzonavano e beffavano l’imperatore e Virgilius, i cani saltassero verso di loro e li trascinassero a terra per morderli a morte.

Così Virgilius riportò in città la pace e l’ordine.

Nel frattempo si era diffusa la fama della figlia del sultano che governava la provincia di Babilonia e in verità si diceva di lei che fosse la principessa più bella del mondo.

Virgilius, come gli altri, ascoltava le storie che venivano narrate su di lei e si innamorò così appassionatamente di tutto ciò che sentì dire che costruì un ponte nell’aria che copriva tutta la distanza tra Roma e Babilonia. Poi lo percorse per visitare la principessa la quale, sebbene fosse piuttosto sorpresa di vederlo, gli diede il benvenuto e dopo aver fatto un po’ di conversazione divenne a sua volta ansiosa di vedere il lontano paese in cui viveva lo straniero e lui promise che ve l’avrebbe portata egli stesso senza che lei si bagnasse le suole delle scarpe.

La principessa trascorse alcuni giorni nel palazzo di Virgilius, osservando meraviglie che non aveva mai sognato, sebbene rifiutasse di accettare i doni dei quali lui desiderava ardentemente colmarla. Le ore trascorsero come minuti finché la principessa di se di non potersi assentare ancora più a lungo da suo padre. Allora Virgilius la condusse personalmente oltre il ponte d’aria e la depose gentilmente sul suo letto, nel quale il padre la trovò il mattino seguente.

Lei gli raccontò tutto ciò che le era accaduto e il sultano finse di essere molto interessato e la pregò di essergli presentato la prossima volta in cui Virgilius fosse venuto.

Ben presto il sultano ricevette un messaggio dalla figlia che lo straniero era arrivato e il sultano ordinò che fosse approntato un banchetto e mandando a chiamare la figlia, consegnò nelle sue mani una coppa che le disse doveva essere offerta a Virgilius stesso, per rendergli onore.

Quando furono tutti seduti al banchetto, la principessa si alzò e presentò la coppa a Virgilius, il quale appena la bevve, cadde in un sonno profondo.

Allora il sultano ordinò alle guardie di legarlo e di lasciarlo dove si trovava fino al giorno seguente.

Appena il sultano si fu alzato, convocò i dignitari e i nobili nella grande sala e ordino che fossero sciolte le corde che legavano Virgilius e che il prigioniero fosse condotto davanti a lui. Nel momento in cui comparve, la collera del sultano esplose e accusò il prigioniero del crimine di aver trasportato la principessa in terre lontane senza permesso.

Virgilius rispose che, se l’aveva portata via, l’aveva anche riportata indietro quando avrebbe potuto trattenerla e che se lo avessero lasciato libero di tornare nel suo paese, lui non sarebbe più tornato.

“Niente di tutto questo!” gridò il sultano “Morirai di una morte vergognosa!” La principessa cadde alle sue ginocchia e lo pregò di poter morire con lui.

“State sbagliando i vostri calcoli, sultano!” disse Virgilius, la cui pazienza si era esaurita, e gettò un incantesimo sul sultano e sui suoi dignitari così che credettero che il grande fiume di Babilonia stesse per inondare la sala e che dovessero nuotare per salvarsi la vita. Così, lasciandoli a tuffarsi e a sguazzare come rane e pesci, Virgilius prese tra le braccia la principessa e la riportò a Roma attraverso il ponte nell’aria.

Virgilius pensava che né il proprio né nessun altro palazzo fosse abbastanza buono per contenere una perla come la principessa, così costruì una città le cui fondamenta posavano su uova, sepolte nelle profondità del mare. In questa città vi era una torre quadrata e in cima alla torre c'era una bacchetta di ferro e dalla bacchetta pendeva una bottiglia, e nella bottiglia era collocato un uovo e dall'uomo pendeva una catena con una mela, che è appesa ancora oggi. Quando l'uovo si muove, la città si scuote e quando l'uovo si romperà, la città sarà distrutta. E la città che Virgilius ha colmato di meraviglie, come mai si erano viste prima, l'ha chiamata Napoli.

Adattamento da Virgilius lo stregone. Origine sconosciuta, tradizione europea.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)