Far, far away, in the midst of a pine forest, there lived a woman who had both a daughter and a stepdaughter. Ever since her own daughter was born the mother had given her all that she cried for, so she grew up to be as cross and disagreeable as she was ugly. Her stepsister, on the other hand, had spent her childhood in working hard to keep house for her father, who died soon after his second marriage; and she was as much beloved by the neighbours for her goodness and industry as she was for her beauty.

As the years went on, the difference between the two girls grew more marked, and the old woman treated her stepdaughter worse than ever, and was always on the watch for some pretext for beating her, or depriving her of her food. Anything, however foolish, was good enough for this, and one day, when she could think of nothing better, she set both the girls to spin while sitting on the low wall of the well.

'And you had better mind what you do,' said she, 'for the one whose thread breaks first shall be thrown to the bottom.'

But of course she took good care that her own daughter's flax was fine and strong, while the stepsister had only some coarse stuff, which no one would have thought of using. As might be expected, in a very little while the poor girl's thread snapped, and the old woman, who had been watching from behind a door, seized her stepdaughter by her shoulders, and threw her into the well.

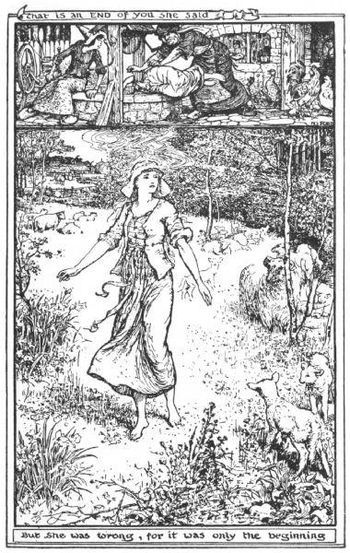

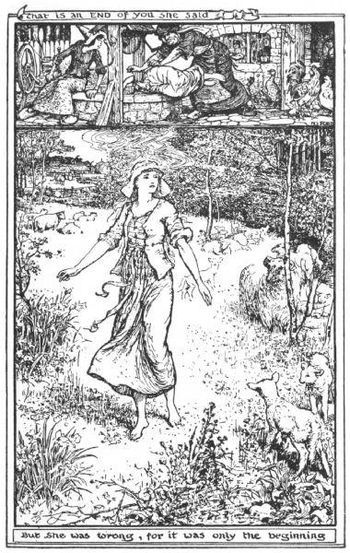

'That is an end of you!' she said. But she was wrong, for it was only the beginning.

Down, down, down went the girl—it seemed as if the well must reach to the very middle of the earth; but at last her feet touched the ground, and she found herself in a field more beautiful than even the summer pastures of her native mountains. Trees waved in the soft breeze, and flowers of the brightest colours danced in the grass. And though she was quite alone, the girl's heart danced too, for she felt happier than she had since her father died. So she walked on through the meadow till she came to an old tumbledown fence - so old that it was a wonder it managed to stand up at all, and it looked as if it depended for support on the old man's beard that climbed all over it.

The girl paused for a moment as she came up, and gazed about for a place where she might safely cross. But before she could move a voice cried from the fence:

'Do not hurt me, little maiden; I am so old, so old, I have not much longer to live.'

And the maiden answered:

'No, I will not hurt you; fear nothing.' And then seeing a spot where the clematis grew less thickly than in other places, she jumped lightly over.

'May all go well with thee,' said the fence, as the girl walked on.

She soon left the meadow and turned into a path which ran between two flowery hedges. Right in front of her stood an oven, and through its open door she could see a pile of white loaves.

'Eat as many loaves as you like, but do me no harm, little maiden,' cried the oven. And the maiden told her to fear nothing, for she never hurt anything, and was very grateful for the oven's kindness in giving her such a beautiful white loaf. When she had finished it, down to the last crumb, she shut the oven door and said: 'Good-morning.'

'May all go well with thee,' said the oven, as the girl walked on.

By-and-by she became very thirsty, and seeing a cow with a milk-pail hanging on her horn, turned towards her.

'Milk me and drink as much as you will, little maiden,' cried the cow, 'but be sure you spill none on the ground; and do me no harm, for I have never harmed anyone.'

'Nor I,' answered the girl; 'fear nothing.' So she sat down and milked till the pail was nearly full. Then she drank it all up except a little drop at the bottom.

'Now throw any that is left over my hoofs, and hang the pail on my horns again,' said the cow. And the girl did as she was bid, and kissed the cow on her forehead and went her way.

Many hours had now passed since the girl had fallen down the well, and the sun was setting.

'Where shall I spend the night?' thought she. And suddenly she saw before her a gate which she had not noticed before, and a very old woman leaning against it.

'Good evening,' said the girl politely; and the old woman answered:

'Good evening, my child. Would that everyone was as polite as you. Are you in search of anything?'

'I am in search of a place,' replied the girl; and the woman smiled and said:

'Then stop a little while and comb my hair, and you shall tell me all the things you can do.'

'Willingly, mother,' answered the girl. And she began combing out the old woman's hair, which was long and white.

Half an hour passed in this way, and then the old woman said:

'As you did not think yourself too good to comb me, I will show you where you may take service. Be prudent and patient and all will go well.'

So the girl thanked her, and set out for a farm at a little distance, where she was engaged to milk the cows and sift the corn.

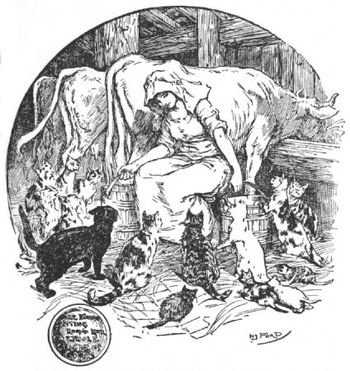

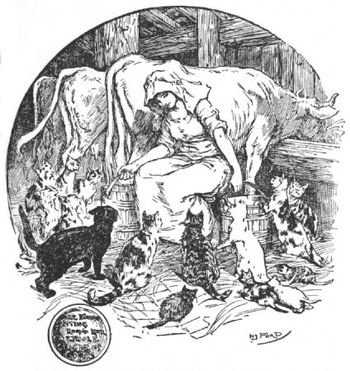

As soon as it was light next morning the girl got up and went into the cow-house. 'I'm sure you must be hungry,' said she, patting each in turn. And then she fetched hay from the barn, and while they were eating it, she swept out the cow-house, and strewed clean straw upon the floor. The cows were so pleased with the care she took of them that they stood quite still while she milked them, and did not play any of the tricks on her that they had played on other dairymaids who were rough and rude. And when she had done, and was going to get up from her stool, she found sitting round her a whole circle of cats, black and white, tabby and tortoise-shell, who all cried with one voice:

'We are very thirsty, please give us some milk!'

'My poor little pussies,' said she, 'of course you shall have some.' And she went into the dairy, followed by all the cats, and gave each one a little red saucerful. But before they drank they all rubbed themselves against her knees and purred by way of thanks.

The next thing the girl had to do was to go to the storehouse, and to sift the corn through a sieve. While she was busy rubbing the corn she heard a whirr of wings, and a flock of sparrows flew in at the window.

'We are hungry; give us some corn! give us some corn!' cried they; and the girl answered:

'You poor little birds, of course you shall have some!' and scattered a fine handful over the floor. When they had finished they flew on her shoulders and flapped their wings by way of thanks.

Time went by, and no cows in the whole country-side were so fat and well tended as hers, and no dairy had so much milk to show. The farmer's wife was so well satisfied that she gave her higher wages, and treated her like her own daughter. At length, one day, the girl was bidden by her mistress to come into the kitchen, and when there, the old woman said to her: 'I know you can tend cows and keep a diary; now let me see what you can do besides. Take this sieve to the well, and fill it with water, and bring it home to me without spilling one drop by the way.'

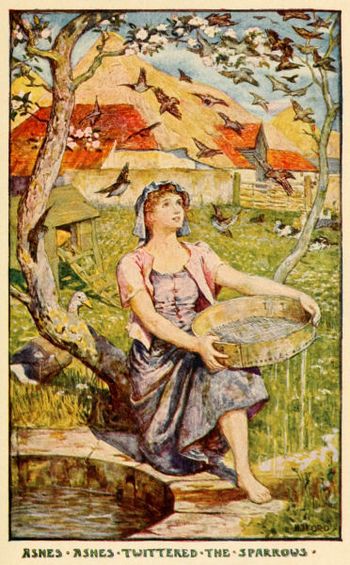

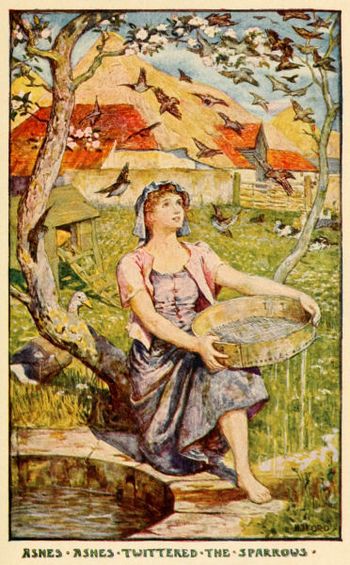

The girl's heart sank at this order; for how was it possible for her to do her mistress's bidding? However, she was silent, and taking the sieve went down to the well with it. Stopping over the side, she filled it to the brim, but as soon as she lifted it the water all ran out of the holes. Again and again she tried, but not a drop would remaining in the sieve, and she was just turning away in despair when a flock of sparrows flew down from the sky.

'Ashes! ashes!' they twittered; and the girl looked at them and said:

'Well, I can't be in a worse plight than I am already, so I will take your advice.' And she ran back to the kitchen and filled her sieve with ashes. Then once more she dipped the sieve into the well, and, behold, this time not a drop of water disappeared!

'Here is the sieve, mistress,' cried the girl, going to the room where the old woman was sitting.

'You are cleverer than I expected,' answered she; 'or else someone helped you who is skilled in magic.' But the girl kept silence, and the old woman asked her no more questions.

Many days passed during which the girl went about her work as usual, but at length one day the old woman called her and said:

'I have something more for you to do. There are here two yarns, the one white, the other black. What you must do is to wash them in the river till the black one becomes white and the white black.' And the girl took them to the river and washed hard for several hours, but wash as she would they never changed one whit.

'This is worse than the sieve,' thought she, and was about to give up in despair when there came a rush of wings through the air, and on every twig of the birch trees which grew by the bank was perched a sparrow.

'The black to the east, the white to the west!' they sang, all at once; and the girl dried her tears and felt brave again. Picking up the black yarn, she stood facing the east and dipped it in the river, and in an instant it grew white as snow, then turning to the west, she held the white yarn in the water, and it became as black as a crow's wing. She looked back at the sparrows and smiled and nodded to them, and flapping their wings in reply they flew swiftly away.

At the sight of the yarn the old woman was struck dumb; but when at length she found her voice she asked the girl what magician had helped her to do what no one had done before. But she got no answer, for the maiden was afraid of bringing trouble on her little friends.

For many weeks the mistress shut herself up in her room, and the girl went about her work as usual. She hoped that there was an end to the difficult tasks which had been set her; but in this she was mistaken, for one day the old woman appeared suddenly in the kitchen, and said to her:

'There is one more trial to which I must put you, and if you do not fail in that you will be left in peace for evermore. Here are the yarns which you washed. Take them and weave them into a web that is as smooth as a king's robe, and see that it is spun by the time that the sun sets.'

'This is the easiest thing I have been set to do,' thought the girl, who was a good spinner. But when she began she found that the skein tangled and broke every moment.

'Oh, I can never do it!' she cried at last, and leaned her head against the loom and wept; but at that instant the door opened, and there entered, one behind another, a procession of cats.

'What is the matter, fair maiden?' asked they. And the girl answered:

'My mistress has given me this yarn to weave into a piece of cloth, which must be finished by sunset, and I have not even begun yet, for the yarn breaks whenever I touch it.'

'If that is all, dry your eyes,' said the cats; 'we will manage it for you.' And they jumped on the loom, and wove so fast and so skilfully that in a very short time the cloth was ready and was as fine as any king ever wore. The girl was so delighted at the sight of it that she gave each cat a kiss on his forehead as they left the room behind one the other as they had come.

'Who has taught you this wisdom?' asked the old woman, after she had passed her hands twice or thrice over the cloth and could find no roughness anywhere. But the girl only smiled and did not answer. She had learned early the value of silence.

After a few weeks the old woman sent for her maid and told her that as her year of service was now up, she was free to return home, but that, for her part, the girl had served her so well that she hoped she might stay with her. But at these words the maid shook her head, and answered gently:

'I have been happy here, Madam, and I thank you for your goodness to me; but I have left behind me a stepsister and a stepmother, and I am fain to be with them once more.' The old woman looked at her for a moment, and then she said:

'Well, that must be as you like; but as you have worked faithfully for me I will give you a reward. Go now into the loft above the store house and there you will find many caskets. Choose the one which pleases you best, but be careful not to open it till you have set it in the place where you wish it to remain.'

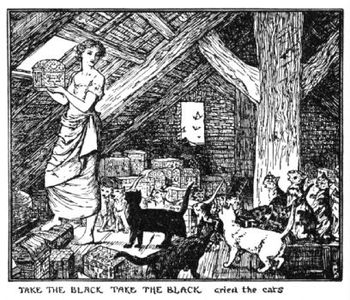

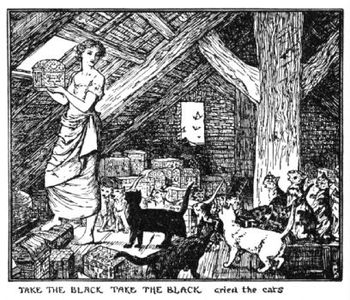

The girl left the room to go to the loft, and as soon as she got outside, she found all the cats waiting for her. Walking in procession, as was their custom, they followed her into the loft, which was filled with caskets big and little, plain and splendid. She lifted up one and looked at it, and then put it down to examine another yet more beautiful. Which should she choose, the yellow or the blue, the red or the green, the gold or the silver? She hesitated long, and went first to one and then to another, when she heard the cats' voices calling: 'Take the black! take the black!'

The words make her look round—she had seen no black casket, but as the cats continued their cry she peered into several corners that had remained unnoticed, and at length discovered a little black box, so small and so black, that it might easily have been passed over.

'This is the casket that pleases me best, mistress,' said the girl, carrying it into the house. And the old woman smiled and nodded, and bade her go her way. So the girl set forth, after bidding farewell to the cows and the cats and the sparrows, who all wept as they said good-bye.

She walked on and on and on, till she reached the flowery meadow, and there, suddenly, something happened, she never knew what, but she was sitting on the wall of the well in her stepmother's yard. Then she got up and entered the house.

The woman and her daughter stared as if they had been turned into stone; but at length the stepmother gasped out:

'So you are alive after all! Well, luck was ever against me! And where have you been this year past?' Then the girl told how she had taken service in the under-world, and, beside her wages, had brought home with her a little casket, which she would like to set up in her room.

'Give me the money, and take the ugly little box off to the outhouse,' cried the woman, beside herself with rage, and the girl, quite frightened at her violence, hastened away, with her precious box clasped to her bosom.

The outhouse was in a very dirty state, as no one had been near it since the girl had fallen down the well; but she scrubbed and swept till everything was clean again, and then she placed the little casket on a small shelf in the corner.

'Now I may open it,' she said to herself; and unlocking it with the key which hung to its handle, she raised the lid, but started back as she did so, almost blinded by the light that burst upon her. No one would ever have guessed that that little black box could have held such a quantity of beautiful things! Rings, crowns, girdles, necklaces - all made of wonderful stones; and they shone with such brilliance that not only the stepmother and her daughter but all the people round came running to see if the house was on fire. Of course the woman felt quite ill with greed and envy, and she would have certainly taken all the jewels for herself had she not feared the wrath of the neighbours, who loved her stepdaughter as much as they hated her.

But if she could not steal the casket and its contents for herself, at least she could get another like it, and perhaps a still richer one. So she bade her own daughter sit on the edge of the well, and threw her into the water, exactly as she had done to the other girl; and, exactly as before, the flowery meadow lay at the bottom. Every inch of the way she trod the path which her stepsister had trodden, and saw the things which she had seen; but there the likeness ended. When the fence prayed her to do it no harm, she laughed rudely, and tore up some of the stakes so that she might get over the more easily; when the oven offered her bread, she scattered the loaves onto the ground and stamped on them; and after she had milked the cow, and drunk as much as she wanted, she threw the rest on the grass, and kicked the pail to bits, and never heard them say, as they looked after her: 'You shall not have done this to me for nothing!'

Towards evening she reached the spot where the old woman was leaning against the gate-post, but she passed her by without a word.

'Have you no manners in your country?' asked the crone.

'I can't stop and talk; I am in a hurry,' answered the girl. 'It is getting late, and I have to find a place.'

'Stop and comb my hair for a little,' said the old woman, 'and I will help you to get a place.'

'Comb your hair, indeed! I have something better to do than that!' And slamming the gate in the crone's face she went her way. And she never heard the words that followed her: 'You shall not have done this to me for nothing!'

By-and-by the girl arrived at the farm, and she was engaged to look after the cows and sift the corn as her stepsister had been. But it was only when someone was watching her that she did her work; at other times the cow-house was dirty, and the cows ill-fed and beaten, so that they kicked over the pail, and tried to butt her; and everyone said they had never seen such thin cows or such poor milk. As for the cats, she chased them away, and ill-treated them, so that they had not even the spirit to chase the rats and mice, which nowadays ran about everywhere. And when the sparrows came to beg for some corn, they fared no better than the cows and the cats, for the girl threw her shoes at them, till they flew in a fright to the woods, and took shelter amongst the trees.

Months passed in this manner, when, one day, the mistress called the girl to her.

'All that I have given you to do you have done ill,' said she, 'yet will I give you another chance. For though you cannot tend cows, or divide the grain from the chaff, there may be other things that you can do better. Therefore take this sieve to the well, and fill it with water, and see that you bring it back without spilling a drop.'

The girl took the sieve and carried it to the well as her sister had done; but no little birds came to help her, and after dipping it in the well two or three times she brought it back empty.

'I thought as much,' said the old woman angrily; 'she that is useless in one thing is useless in another.'

Perhaps the mistress may have thought that the girl had learnt a lesson, but, if she did, she was quite mistaken, as the work was no better done than before. By-and-by she sent for her again, and gave her maid the black and white yarn to wash in the river; but there was no one to tell her the secret by which the black would turn white, and the white black; so she brought them back as they were. This time the old woman only looked at her grimly but the girl was too well pleased with herself to care what anyone thought about her.

After some weeks her third trial came, and the yarn was given her to spin, as it had been given to her stepsister before her.

But no procession of cats entered the room to weave a web of fine cloth, and at sunset she only brought back to her mistress an armful of dirty, tangled wool.

'There seems nothing in the world you can do,' said the old woman, and left her to herself.

Soon after this the year was up, and the girl went to her mistress to tell her that she wished to go home.

'Little desire have I to keep you,' answered the old woman, 'for no one thing have you done as you ought. Still, I will give you some payment, therefore go up into the loft, and choose for yourself one of the caskets that lies there. But see that you do not open it till you place it where you wish it to stay.'

This was what the girl had been hoping for, and so rejoiced was she, that, without even stopping to thank the old woman, she ran as fast as she could to the loft. There were the caskets, blue and red, green and yellow, silver and gold; and there in the corner stood a little black casket just like the one her stepsister had brought home.

'If there are so many jewels in that little black thing, this big red one will hold twice the number,' she said to herself; and snatching it up she set off on her road home without even going to bid farewell to her mistress.

'See, mother, see what I have brought!' cried she, as she entered the cottage holding the casket in both hands.

'Ah! you have got something very different from that little black box,' answered the old woman with delight. But the girl was so busy finding a place for it to stand that she took little notice of her mother.

'It will look best here—no, here,' she said, setting it first on one piece of furniture and then on another. 'No, after all it is to fine to live in a kitchen, let us place it in the guest chamber.'

So mother and daughter carried it proudly upstairs and put it on a shelf over the fireplace; then, untying the key from the handle, they opened the box. As before, a bright light leapt out directly the lid was raised, but it did not spring from the lustre of jewels, but from hot flames, which darted along the walls and burnt up the cottage and all that was in it and the mother and daughter as well.

As they had done when the stepdaughter came home, the neighbours all hurried to see what was the matter; but they were too late. Only the hen-house was left standing; and, in spite of her riches, there the stepdaughter lived happily to the end of her days.

From Thorpe’s Yule-Tide Stories.

I due cofanetti

Lontano lontano, nel cuore di una foresta di pini, viveva una donna che aveva una figlia e una figliastra. Sin da quando la figlia era nata, la madre le aveva dato tutto ciò che aveva preteso, così era cresciuta tanto bisbetica e sgradevole quanto era brutta. La sorellastra, d’altro canto, aveva trascorso l’infanzia lavorando duramente per accudire la casa di suo padre, che era morto poco dopo il secondo matrimonio, ed era assai amata dai vicini per la bontà e l’operosità e per la bellezza.

Con il passare degli anni le differenze tra le due ragazze erano più evidenti e la vecchia trattava peggio che mai la figliastra, era sempre in cerca di pretesti per picchiarla o privarla del cibo. Qualsiasi scusa, persino la più folle, andava abbastanza bene per lei e un giorno, non venendole in mente nulla di meglio, mandò entrambe le ragazze a filare mentre sedevano sul bordo del pozzo.

”E fareste meglio a badare a ciò che fate,” disse, “perché quella a cui si romperà per prima il filo finirà giù in fondo.”

Naturalmente si curò che il lino della figlia fosse sottile e resistente, mentre la sorellastra ebbe solo materiale grezzo, che nessun altro si sarebbe sognato di usare. Come c’era da aspettarsi, in pochissimo tempo il filo della povera ragazza si spezzò e la vecchia, che aveva osservato da dietro la porta, afferrò la figliastra le per spalle e la gettò nel pozzo.

”Questa è la tua fine!” disse. Ma si sbagliava, perché era solo l’inizio.

La ragazza andò giù, giù, giù – sembrava che il pozzo dovesse raggiungere il centro della terra; ma alla fine i suoi piedi toccarono il terreno e lei si trovò in un campo assai più bello dei pascoli estivi delle sue montagne natie. Gli alberi oscillavano nella leggera brezza, fiori dai colori più luminosi danzavano nell’erba. E sebbene fosse completamente sola, anche il cuore della ragazza balzò, perché si sentiva più felice di quanto fosse stata da quando era morto suo padre. Così camminò attraverso i prati finché giunse a una vecchia staccionata in rovina – così vecchio che era un miracolo riuscisse ancora a reggersi dritta, e sembrava che ciò dipendesse dal sostegno della barba di un vecchio uomo la quale vi si avvolgeva tutta intorno.

La ragazza si fermò un momento come fu vicina e guardò se vi fosse un punto in cui potesse attraversarlo con sicurezza. Ma prima che si muovesse, una voce gridò dalla staccionata:

”Non farmi del male, ragazzina; sono così vecchio, non mi rimane molto da vivere.”

La ragazza rispose:

”No, non ti farò del male, non temere.” E vedendo uno spazio in cui la clematide cresceva meno fitta che in altri punti, la oltrepassò con un leggiadro salto.

”Che tutto possa andarti bene,” disse la staccionata, mentre la ragazza andava via.

Ben presto lasciò il prato e si trovò su un sentiero che correva tra due bordure di fiori. A destra di fronte a lei c’era un forno e attraverso la sua bocca aperta poté vedere una catasta di pagnotte bianche.

”Mangia quante pagnotte vuoi, ma non farmi del male, ragazzina.” gridò il forno. La ragazza gli disse di non avere paura perché lei non aveva mai danneggiato nulla, e fu molto grata per la gentilezza con cui il forno le offriva un tale meraviglioso pane bianco. Quando ebbe finito, sino all’ultima briciola, chiuse la bocca del forno e disse: “Buongiorno.”

”Che tutto possa andarti bene.” disse il forno, mentre la ragazza andava via.

Di li a poco ebbe molta sete e vedendo una mucca con un secchio per il latte appeso a un corno, si diresse verso di essa.

”Mungimi e bevi quanto vuoi, ragazzina,” esclamò la mucca, “ma assicurati di non rovesciarne sul terreno; e non farmi del male perché io non ne ho mai fatto a nessuno.”

”Neppure io,” rispose la ragazza “non temere.” Così sedette e munse la mucca finché il secchio fu colmo, poi lo bevve tutto tranne una goccia sul fondo.

”Ora getta sul mio zoccolo ciò che è rimasto e appendi di nuovo il secchio alle corna.” disse la mucca. La ragazza fece come le era stato detto, baciò in fronte la mucca e proseguì per la propria strada.

Erano trascorse molte ore da quando la ragazza era caduta nel pozzo e il sole stava tramontando.

”Dove passerò la notte?” pensava. E all’improvviso vide davanti a sé un cancello di cui non si era accorta prima e una donna assai vecchia che vi si appoggiava.

”Buonasera.” disse educatamente la ragazza e la vecchia rispose:

”Buonasera, bambina mia. Magari fossero tutti educati come te. Stai cercando qualcosa?”

”Sono in cerca di un rifugio.” rispose la ragazza; la donna sorrise e disse:

”Allora fermati per un po’ e pettinami i capelli, poi mi dirai tutto ciò che vuoi fare.”

”Volentieri, madre.” rispose la ragazza. Cominciò così a pettinare i capelli della donna, che erano lunghi e candidi.

Passò mezz’ora in questo modo e poi la vecchia disse:

””Siccome non hai pensato di avere troppa stima di te per pettinarmi, ti mostrerò dove potrai andare a servizio. Sii prudente e paziente e tutto andrà bene.”

Così la ragazza la ringraziò e si diresse verso una fattoria poco lontana, dove fu assunta per mungere le mucche e setacciare il grano.

Appena il mattino successivo si fece luce, la ragazza si alzò e andò nella stalla. “Sono certa che dovete avere fame.” disse, dando un colpetto a ciascuna. E allora andò a prendere il fieno nel fienile e, mentre stavano mangiando, spazzò la stalla e sparse paglia pulita sul pavimento. Le mucche ne furono così contente per come si prendeva cura di loro che stettero buone mentre le mungeva e non le giocarono nessuno dei soliti scherzi che erano solite fare alle altre lavoranti che erano rozze e sgarbate. E quando ebbe finito, e si stava alzando dallo sgabello, si trovò circondata di gatti, bianchi e neri, tigrati e maculati, che gridavano a una sola voce:

”Abbiamo tanta sete, per favore dacci un po’ di latte!”

”Miei poveri gattini,” disse lei, “Naturalmente ne avrete un po’.” Andò nella latteria, seguita da tutti i gatti, e diede a ciascuno un piattino rosso colmo. Prima di bere, si strofinarono tutti contro le sue ginocchia e fecero le fusa per ringraziarla.

Il successive compito della ragazza era andare nel magazzino e setacciare il grano con un crivello. Mentre era occupata a sfregare il grano, udì un frullo d’ali e uno stormo di passeri volò dentro attraverso la finestra.

”Siamo affamati, dacci un po’ di grano! Dacci un po’ di grano!” gridarono, e la ragazza rispose:

”Poveri uccellini, naturalmente ne avrete un po’!” e ne sparse una bella manciata sul pavimento. Quando ebbero finito, volarono sulle sue spalle e sbatterono le ali per ringraziarla.

Il tempo passava e in tutto il paese non c’erano mucche grasse e ben tenute come le sue, e nessuna latteria aveva tanto latte da offrire. La moglie del fattore era così soddisfatta che le aveva dato una paga più alta e la trattava come una figlia. Finalmente un giorno la padrona le ordinò di andare in cucina e quando fu lì, la vecchia le disse: “So che puoi condurre le mucche e provvedere a un deposito; adesso vediamo che altro puoi fare. Prendi questo setaccio al pozzo e riempilo d’acqua, poi portamelo a casa senza perdere una goccia per strada.”

A quest’ordine il cuore della ragazza cedette; come le sarebbe stato possibile eseguire l’ordine della padrona? In ogni modo rimase in silenzio, e prendendo il setaccio andò con esso al pozzo. Fermandosi di lato, lo riempì fino all’orlo, ma appena lo sollevava, l’acqua scorreva via dai fori. Provò e riprovò, ma non una goccia restava nel setaccio e stava per cedere alla disperazione quando scese dal cielo uno stormi di passeri.

”Cenere! Cenere!” cinguettarono; la ragazza li guardò e disse:

”Beh, non potrò trovarmi in una situazione peggiore di quella in cui già sono, così seguirò il vostro consiglio.” E corse in cucina e riempì di cenere il setaccio. Poi immerse un’altra volta il setaccio nel pozzo e, guarda un po’, stavolta non uscì una goccia d’acqua!

”Ecco il setaccio, padrona,” esclamò la ragazza, entrando nella stanza in cui si trovava la vecchia.

”Sei più intelligente di quanto mi aspettassi,” rispose lei, “oppure ti ha aiutata qualcuno che è esperto di magia.” La ragazza restò in silenzio e la vecchia non le fece altre domande.

Trascorsero vari giorni durante i quali la ragazza svolse come il solito il proprio lavoro, ma improvvisamente la vecchia la chiamò e disse:

”Ho qualcos’altro da farti fare. Là ci sono due filati, uno bianco e l’altro nero. Ciò che devi fare è lavarli nel fiume finché quello nero diventi bianco e quello bianco diventi nero.” La ragazza li portò al fiume e li lavò per diverse ore, ma per quanto li lavasse, non cambiavano neanche un po’.

”È peggio del setaccio.” pensò e stava per abbandonarsi alla disperazione quando nell’aria vi fu un frullo d’ali e su ogni ramo delle betulle che crescevano sulla riva c’era appollaiato un passero.

”Il filato nero a est, e quello bianco a ovest!” cantarono ad un tratto; la ragazza si asciugò le lacrime e riprese di nuovo coraggio. Afferrando il filato nero, mi mise rivolta a est, lo immerse nel fiume e in un attimo diventò bianco come la neve; allora si rivolse a ovest, tenne il filato bianco nell’acqua e diventò nero come l’ala di un corvo. Si volse indietro verso i passeri, sorrise e fece loro un cenno; sbattendo le ali in risposta, volarono via rapidamente.

Alla vista dei filati la vecchia ammutolì; quando infine ritrovò la parola, chiese alla ragazza quale mago l’avesse aiutata a fare ciò che nessuno aveva fatto prima. La ragazza non rispose perché temeva di mettere in difficoltà i piccoli amici.

Per un po’ di settimane la padrona si chiuse nella propria stanza e la ragazza proseguì con il lavoro come il solito. Sperava che fossero finite le difficili prove che le avevano imposto; in ciò si sbagliava, perché un giorno la vecchia comparve improvvisamente in cucina e le disse:

”C’è ancora una prova alla quale ti devo sottoporre e se non fallirai, sarai lasciata in pace per sempre. Qui ci sono i filati che hai lavato. Prendili e intrecciali in una rete che sia morbida come la veste di un re, e bada che sia filata entro il tramonto.”

”È la cosa più facile che mi sia stata data da fare.” pensò la ragazza, che era un’abile filatrice. Ma quando cominciò, si accorse che la matassa era ingarbugliata e si spezzava continuamente.

”Oh, non ce la farò mai!” esclamò alla fine, poi chinò la testa sul telaio e pianse, ma in quel momento si aprì la porta ed entrò una fila di gatti, uno dietro l’altro.

”Qual è il problema, bella fanciulla?” chiesero. E la ragazza rispose:

”La padrona mi ha dato questo filato da intrecciare in un pezzo di stoffa, e deve essere finito entro il tramonto, ma io non ho ancora incominciato perché il filato si rompe ogni volta in cui lo tocco.”

”Se è tutto qui, asciugati gli occhi,” dissero i gatti; “lo faremo per te.” E balzarono sul telaio e filarono così rapidamente e così abilmente che in brevissimo tempo l’abito fu pronto ed era così leggero che qualsiasi re avrebbe potuto indossarlo. La ragazza era così contenta alla vista di ciò che diede a ciascun gatto un bacio sulla fronte mentre lasciavano la stanza uno dietro l’altro, come erano venuti.

”Chi ti ha fatto apprendere questa sapienza?” chiese la vecchia, dopo che ebbe passato mano due o tre volte sull’abito senza poter trovare ruvidezza da nessuna parte. La ragazza sorrise e non rispose. Aveva imparato presto il valore del silenzio.

Dopo poche settimane, la vecchia mandò a chiamare la ragazza e le disse che l’anno di servizio era finite, che era libera di tornare a casa ma che, da parte sua, aveva servitor così bene che sperava potesse restare con lei. Ma a queste parole la ragazza scosse la testa e rispose garbatamente:

”Sono stata felice qui, signora, e vi ringrazio per la bontà che mi avete mostrato; però ho lasciato una matrigna e una sorellastra e son disposta a stare di nuovo con loro. “ la vecchia la guardò un momento e poi disse:

Ebbene sia come vuoi tu, ma siccome ai lavorato fedelmente per me, ti darò una ricompensa. Adesso vai nella soffitta sopra il magazzino e lì troverai alcuni cofanetti. Scegli quello che ti piace di più, ma fai attenzione a non aprirlo finché non l’avrai deposto nel luogo in cui desideri rimanere.”

La ragazza lasciò la stanza per andare nella soffitta, e appena fu uscita, trovò tutti I gatti che la stavano aspettando. Camminando in fila, com’era loro abitudine, la seguirono nella soffitta che era piena di cofanetti grandi e piccoli, disadorni e lussuosi. Ne sollevò uno e lo guardò, poi lo mise giù per osservarne un altro più bello. Quale avrebbe scelto, quello giallo o blu, quello rosso o verde, quello d’oro o d’argento? Esitò a lungo, andando da uno all’altro, quando sentì le voci dei gatti che dicevano: “Prendi quello nero! Prendi quello nero!”

A quelle parole si guardò attorno – non aveva visto nessun cofanetto nero, ma siccome I gatti continuavano a dirlo, scrutò negli altri angoli che erano rimasti inesplorati e alla fine scoprì una scatoletta nera, così piccola e così nera che facilmente sarebbe passata inosservata.

”È questo il cofanetto che mi piace di più, padrona.” disse la ragazza, portandolo in casa. La vecchia sorrise, fece un cenno con la testa e le disse di andare per la propria strada. Così la ragazza si avviò, dopo aver detto addio alle mucche, ai gatti e ai passeri, che piansero tutti nel salutarla.

Andò avanti e avanti finché giunse nel prato fiorito e lì, improvvisamente, accadde qualcosa, ma non avrebbe saputo dire che cosa, e si ritrovò seduta sul pozzo nel cortile della matrigna. Allora scese ed entrò in casa.

La donna e sua figlia la fissarono come se fossero diventate di pietra, ma alla fine la matrigna ansimò:

”Così dopotutto sei viva! Bene, la sfortuna mi perseguita! E dove sei stata per tutto questo anno?” allora la ragazza le disse che aveva stata a servizio nel mondo di sotto e, oltre la paga, aveva portato a casa un cofanetto che le sarebbe piaciuto mettere nella propria stanza.

”Dammi il denaro e porta quella brutta scatoletta nella rimessa.” gridò la donna, fuori di sé dalla rabbia, e la ragazza, piuttosto spaventata dalla sua violenza, si allontanò in fretta con la preziosa scatola stretta al petto.

La rimessa era assai sporca, siccome nessuno vi si era più avvicinato dopo che la ragazza era caduta nel pozzo; ma lei strofinò e spazzò finché ogni cosa fu di nuovo pulita e poi mise il cofanetto su una mensolina in un angolo.

”Adesso posso aprirlo.” si disse; e aprendolo la serratura con la chiave che portava appesa al braccio, sollevò il coperchio ma indietreggiò dopo averlo fatto, quasi accecata dalla luce che esplose vicino a lei. Nessuno avrebbe mai immaginato che quel cofanetto nero potesse contenere una tale quantità di cose meravigliose! Anelli, corone, cinture, collane – tutte fatte di meravigliose pietre; e emanavano una tale luce che non solo la matrigna e la sorellastra ma tutta la gente del vicinato corse a vedere se la casa andasse a fuoco. Naturalmente la donna quasi morì di avidità e di invidia, e certamente avrebbe preso per sé tutti i gioielli se non avesse temuto la collera dei vicini che amavano la sua figliastra tanto quanto lei la odiava.

Se però non poteva appropriarsi del cofanetto e di ciò che conteneva, avrebbe potuto prenderne un altro simile e forse ancora più ricco. Così ordinò alla figlia di sedere sull’orlo del pozzo e la gettò nell’acqua, proprio come aveva con l’altra fanciulla; e esattamente come prima, in fondo c’era il prato fiorito.

In tutto e per tutto seguì il sentiero che aveva già percorso la sorellastra, e vide le medesime cose che aveva visto lei; ma le somiglianze finiscono qui. Quando la staccionata la pregò di non farle male, lei rise sguaiatamente e staccò alcune stecche per poter passare più agevolmente; quando il forno le offrì il pane, sparpagliò le pagnotte a terra e le calpestò; e dopo che ebbe munto la mucca ed ebbe bevuto quanto voleva, gettò la rimanenza nell’erba e fece a pezzi a calci il secchio, neppure sentendo che dicevano, dopo averla guardata: “Non avresti dovuto per nulla farmi ciò!”

Verso sera raggiunse la radura in cui la vecchia era appoggiata al cancello, ma la oltrepassò senza dire una parola.

”Non conoscete le buone maniere al tuo paese?” chiese la vecchia.

”Non posso fermarmi a parlare, vado di fretta,” rispose la ragazza. “Si è fatto tardi e devo trovare un posto.”

”Fermati a pettinarmi i capelli per un po’,” disse la vecchia, “e ti aiuterò a trovare un posto.”

“Ma davvero, pettinarti i capelli! Ho di meglio da fare!” E, sbattendo il cancello in faccia alla vecchia, proseguì per la propria strada. E non udì le parole che le furono rivolte: “Non avresti dovuto per nulla farmi ciò!”

Di lì a poco la ragazza giunse alla fattoria e fu assunta per badare alle mucche e setacciare il grano come aveva fatto al sorellastra. Ma svolgeva il proprio lavoro solo se qualcuno la guardava; altrimenti la stalla era sporca e le mucche malnutrite e percosse, così calciavano via il secchio e tentavano di incornarla; e tutti dicevano che non si erano mai viste mucche così magre e così poco latte. Riguardo i gatti, li inseguiva e li maltrattava, cosicché non avevano voglia di inseguire ratti e topi, che scorazzavano dappertutto. E quando i passeri vennero a chiederle un po’ di grano, non furono trattati meglio delle mucche e dei gatti perché la ragazza lanciò contro di loro le proprie scarpe finché volarono nel bosco per lo spavento e si rifugiarono fra i rami.

Trascorsero alcuni mesi in questo modo quando, un giorno, la padrona chiamò a sé la ragazza. “Tutto ciò che ti ho detto di fare, lo hai fatto male,” disse, “tuttavia ti darò un’altra possibilità. Sebbene tu non abbia governato le mucche o separato il grano dalla pula, ci sono altre cose che potrai fare meglio. Perciò porta questo setaccio al pozzo e riempilo d’acqua, badando che non ne cada neppure una goccia.”

La ragazza prese il setaccio e lo portò al pozzo come aveva fatto la sorella, ma gli uccellini non vennero ad aiutarla e, dopo averlo immerse nel pozzo due o tre volte, lo riportò indietro vuoto.

La donna disse irosamente: “Penso che sia proprio incapace in una cosa come in un’altra.”

Può darsi la donna avesse pensato che la ragazza avesse imparato la lezione, ma, se lo aveva fatto, si era sbagliata di grosso, perché il lavoro non fu fatto meglio di prima. Di lì a poco la chiamò di nuovo e diede alla ragazza il filato nero e quello bianco da lavare nel fiume; ma non c’era nessuno a rivelarle il segreto grazie al quale quello nero sarebbe diventato bianco e il bianco, nero; così li riportò tali e quali erano. Stavolta la vecchia si limitò a gettarle un’occhiata torva, ma la ragazza era troppo compiaciuta per preoccuparsi di ciò che qualcuno pensasse di lei.

Dopo alcune settimane ci fu la terza prova e le fu dato il filato da tessere, come era accaduto alla sorellastra prima di lei.

Non entrarono nella stanza I gatti in fila a filare una rete di leggiadro tessuto e al tramonto riportò alla padrona solo una bracciata di filato sporco e ingarbugliato.

”Sembra proprio non esista al mondo nulla che tu possa fare.” disse la vecchia, e l’abbandonò a se stessa.

Ben presto l’anno finì e la ragazza andò a dire alla padrona che desiderava tornare a casa.

”Ho assai poca voglia di trattenerti,” rispose la vecchia, “visto che non hai fato una sola delle cose che ti son state chieste. Tuttavia ti pagherò in qualche modo, perciò vai in soffitta e scegli uno dei cofanetti che si trovano lì. Ma bada bene di non aprirlo finché non l’avrai messo dove vuoi che stia.”

Era ciò che la ragazza aveva sperato perciò, contentissima, corse in soffitta più in fretta che poté. Lì c’erano i cofanetti, blu e rossi, verdi e gialli, d’argento e d’oro; e in un angolo c’era un cofanetto nero proprio come quello che aveva portato a casa la sorellastra.

”Se c’erano così tanti gioielli in quell’oggettino nero, in questo grosso cofanetto rosso ce ne sarà il doppio.” si disse e, afferratolo, riprese la strada di casa senza neppure dire addio alla padrona.

”Guarda, mamma, guarda che cosa ho portato!” gridò appena fu entrata nella casetta, sorreggendo il cofanetto con entrambe le mani.

”Ah! Hai preso qualcosa di molto diverso da quella scatoletta near.” rispose soddisfatta la donna. Ma la ragazza era così occupata a trovare un posto per metterlo che non si curò della madre.

”Lo vedo bene qui –no, qui.” diceva, mettendolo prima su un mobile e poi su un altro. “No, dopotutto è troppo bello per la cucina, lo metterò nella stanza degli ospiti.

Così madre e figlia lo portarono orgogliosamente di sopra e lo misero su una mensola sopra il caminetto; poi, liberando la chiave dalla maniglia, aprirono il cofanetto. Come la volta precedente si sprigionò un’ intensa luce quando il coperchio fu sollevato, ma non proveniva dallo splendore dei gioielli bensì dalle fiamme divamparono sui muri e bruciarono la casa con tutto ciò che conteneva, comprese madre e figlia.

Come avevano fatto quando era tornata la sorellastra, i vicini accorsero a vedere che cosa fosse successo, ma giunsero troppo tardi. Restava in piedi solo il pollaio e lì, malgrado le ricchezze, visse felice contenta la sorellastra, fino alla fine dei suoi giorni.

Dalla raccolta “Storie natalizie di Benjamin Thorpe

NdT: Questa raccolta contiene fiabe popolari e tradizionali della Svezia, della Danimarca, della Norvegia e della Germania del Nord . Fu pubblicata a Londra nel 1910.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)