Once upon a time there was a peasant whose wife died, leaving him with two children—twins—a boy and a girl. For some years the poor man lived on alone with the children, caring for them as best he could; but everything in the house seemed to go wrong without a woman to look after it, and at last he made up his mind to marry again, feeling that a wife would bring peace and order to his household and take care of his motherless children. So he married, and in the following years several children were born to him; but peace and order did not come to the household. For the step-mother was very cruel to the twins, and beat them, and half-starved them, and constantly drove them out of the house; for her one idea was to get them out of the way. All day she thought of nothing but how she should get rid of them; and at last an evil idea came into her head, and she determined to send them out into the great gloomy wood where a wicked witch lived. And so one morning she spoke to them, saying:

'You have been such good children that I am going to send you to visit my granny, who lives in a dear little hut in the wood. You will have to wait upon her and serve her, but you will be well rewarded, for she will give you the best of everything.'

So the children left the house together; and the little sister, who was very wise for her years, said to the brother:

'We will first go and see our own dear grandmother, and tell her where our step-mother is sending us.'

And when the grandmother heard where they were going, she cried and said:

'You poor motherless children! How I pity you; and yet I can do nothing to help you! Your step-mother is not sending you to her granny, but to a wicked witch who lives in that great gloomy wood. Now listen to me, children. You must be civil and kind to everyone, and never say a cross word to anyone, and never touch a crumb belonging to anyone else. Who knows if, after all, help may not be sent to you?'

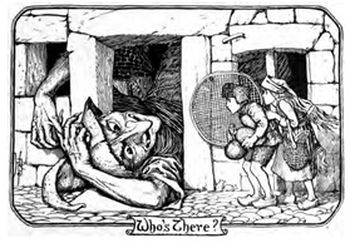

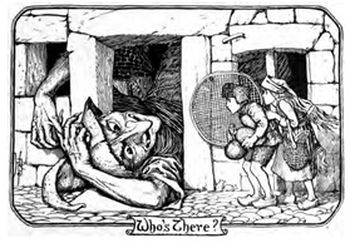

And she gave her grandchildren a bottle of milk and a piece of ham and a loaf of bread, and they set out for the great gloomy wood. When they reached it they saw in front of them, in the thickest of the trees, a queer little hut, and when they looked into it, there lay the witch, with her head on the threshold of the door, with one foot in one corner and the other in the other corner, and her knees cocked up, almost touching the ceiling.

'Who's there?' she snarled, in an awful voice, when she saw the children.

And they answered civilly, though they were so terrified that they hid behind one another, and said:

'Good-morning, granny; our step-mother has sent us to wait upon you, and serve you.'

'See that you do it well, then,' growled the witch. 'If I am pleased with you, I'll reward you; but if I am not, I'll put you in a pan and fry you in the oven—that's what I'll do with you, my pretty dears! You have been gently reared, but you'll find my work hard enough. See if you don't.'

And, so saying, she set the girl down to spin yarn, and she gave the boy a sieve in which to carry water from the well, and she herself went out into the wood. Now, as the girl was sitting at her distaff, weeping bitterly because she could not spin, she heard the sound of hundreds of little feet, and from every hole and corner in the hut mice came pattering along the floor, squeaking and saying:

Little girl, why are your eyes so red?

If you want help, then give us some bread.

And the girl gave them the bread that her grandmother had given her. Then the mice told her that the witch had a cat, and the cat was very fond of ham; if she would give the cat her ham, it would show her the way out of the wood, and in the meantime they would spin the yarn for her. So the girl set out to look for the cat, and, as she was hunting about, she met her brother, in great trouble because he could not carry water from the well in a sieve, as it came pouring out as fast as he put it in. And as she was trying to comfort him they heard a rustling of wings, and a flight of wrens alighted on the ground beside them. And the wrens said:

Give us some crumbs, then you need not grieve

For you'll find that water will stay in the sieve.

Then the twins crumbled their bread on the ground, and the wrens pecked it, and chirruped and chirped. And when they had eaten the last crumb they told the boy to fill up the holes of the sieve with clay, and then to draw water from the well. So he did what they said, and carried the sieve full of water into the hut without spilling a drop. When they entered the hut the cat was curled up on the floor. So they stroked her, and fed her with ham, and said to her:

'Pussy, grey pussy, tell us how we are to get away from the witch?'

Then the cat thanked them for the ham, and gave them a pocket-handkerchief and a comb, and told them that when the witch pursued them, as she certainly would, all they had to do was to throw the handkerchief on the ground and run as fast as they could. As soon as the handkerchief touched the ground a deep, broad river would spring up, which would hinder the witch's progress. If she managed to get across it, they must throw the comb behind them and run for their lives, for where the comb fell a dense forest would start up, which would delay the witch so long that they would be able to get safely away.

The cat had scarcely finished speaking when the witch returned to see if the children had fulfilled their tasks.

'Well, you have done well enough for to-day,' she grumbled; 'but to-morrow you'll have something more difficult to do, and if you don't do it well, you pampered brats, straight into the oven you go.'

Half-dead with fright, and trembling in every limb, the poor children lay down to sleep on a heap of straw in the corner of the hut; but they dared not close their eyes, and scarcely ventured to breathe. In the morning the witch gave the girl two pieces of linen to weave before night, and the boy a pile of wood to cut into chips. Then the witch left them to their tasks, and went out into the wood. As soon as she had gone out of sight the children took the comb and the handkerchief, and, taking one another by the hand, they started and ran, and ran, and ran. And first they met the watch-dog, who was going to leap on them and tear them to pieces; but they threw the remains of their bread to him, and he ate them and wagged his tail. Then they were hindered by the birch-trees, whose branches almost put their eyes out. But the little sister tied the twigs together with a piece of ribbon, and they got past safely, and, after running through the wood, came out on to the open fields.

In the meantime in the hut the cat was busy weaving the linen and tangling the threads as it wove. And the witch returned to see how the children were getting on; and she crept up to the window, and whispered:

'Are you weaving, my little dear?'

'Yes, granny, I am weaving,' answered the cat.

When the witch saw that the children had escaped her, she was furious, and, hitting the cat with a porringer, she said: 'Why did you let the children leave the hut? Why did you not scratch their eyes out?'

But the cat curled up its tail and put its back up, and answered: 'I have served you all these years and you never even threw me a bone, but the dear children gave me their own piece of ham.'

Then the witch was furious with the watch-dog and with the birch-trees, because they had let the children pass. But the dog answered:

'I have served you all these years and you never gave me so much as a hard crust, but the dear children gave me their own loaf of bread.'

And the birch rustled its leaves, and said: 'I have served you longer than I can say, and you never tied a bit of twine even round my branches; and the dear children bound them up with their brightest ribbons.'

So the witch saw there was no help to be got from her old servants, and that the best thing she could do was to mount on her broom and set off in pursuit of the children. And as the children ran they heard the sound of the broom sweeping the ground close behind them, so instantly they threw the handkerchief down over their shoulder, and in a moment a deep, broad river flowed behind them.

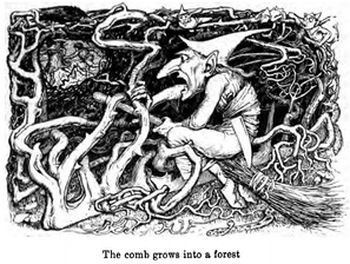

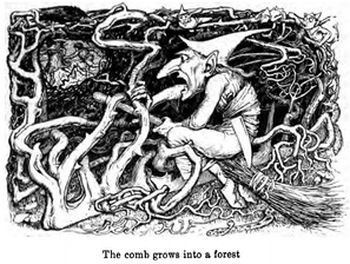

When the witch came up to it, it took her a long time before she found a place which she could ford over on her broom-stick; but at last she got across, and continued the chase faster than before. And as the children ran they heard a sound, and the little sister put her ear to the ground, and heard the broom sweeping the earth close behind them; so, quick as thought, she threw the comb down on the ground, and in an instant, as the cat had said, a dense forest sprung up, in which the roots and branches were so closely intertwined, that it was impossible to force a way through it. So when the witch came up to it on her broom she found that there was nothing for it but to turn round and go back to her hut.

But the twins ran straight on till they reached their own home. Then they told their father all that they had suffered, and he was so angry with their step-mother that he drove her out of the house, and never let her return; but he and the children lived happily together; and he took care of them himself, and never let a stranger come near them.

Froma the Russian.

La strega

C’era una volta un contadino la cui moglie era morta, lasciandogli due gemelli, un maschio e una femmina. Per alcuni anni il pover’uomo visse da solo con i bambini, curandosi di loro meglio che poté; ma tutto in casa sembrava andar peggio senza una donna che se ne occupasse e alla fine decise di sposarsi di nuovo, pensando che una moglie avrebbe portato pace e ordine in casa e si sarebbe presa cura dei suoi bambini orfani. Così si sposò e negli anni successivi nacquero dei bambini; ma la pace e l’ordine non entrarono in casa. La matrigna era molto crudele con i gemelli, li picchiava, li lasciava quasi morire di fame e li mandava sempre fuori di casa perché sa sua idea fissa era allontanarli. Per tutto il giorno non pensava ad altro che a sbarazzarsi di loro e alla fine le venne una malvagia idea e decise di mandarli nel grande bosco oscuro in cui viveva una strega. E così una mattina parlò loro, dicendo:

“Siete dei bambini tanto bravi che vi voglio mandare a far visita a mia nonna che vive in una graziosa casetta nel bosco. Dovrete fermarvi da lei e servirla, ma sarete ben ricompensati perché vi darà il meglio di tutto.”

Così i bambini lasciarono insieme la casa e la sorellina, che era molto saggia per i suoi sette anni, disse al fratello:

“Prima andremo a a trovare nostra nonna e le diremo dove ci sta mandando la matrigna.”

Quando la nonna sentì dove stessero andando, pianse e disse.

“Poveri bambini senza mamma! Ho pietà di voi e tuttavia non posso fare nulla per aiutarvi! La vostra matrigna non vi sta mandando da sua nonna, ma da una malvagia strega che vive nel grande bosco tenebroso. Ascoltatemi, bambini. Dovete essere educati e gentili con tutti e non dire mai parole sgarbate a nessuno non toccare una briciola che non vi appartenga. Chi può sapere, dopo tutto, che non possiate ricevere aiuto?”

Diede ai nipoti una bottiglia di latte, un pezzo di prosciutto e una pagnotta di pane e loro s’incamminarono verso il grande bosco tenebroso. Quando l’ebbero raggiunto, videro di fronte a loro, nel folto degli alberi, una bizzarra casetta e quando guardarono dentro videro che la strega era sdraiata con la testa sulla soglia di casa, con un piede in un angolo e uno nell’altro e con le ginocchia sollevate che quasi toccavano il soffitto.

“Chi siete?” ringhiò con voce spaventosa quando vide i bambini.

E loro risposero educatamente, sebbene fossero così terrorizzati da nascondersi l’uno dietro l’altra, e dissero:

“Buongiorno, nonna, la nostra matrigna ci ha mandato per stare da te e servirti.”

“Allora badate di farlo bene,” borbottò la strega “se mi accontenterete, vi ricompenserò, ma se non sarò soddisfatta, vi trasformerò in un teglia e vi cuocerò nel forno… ecco che cosa farò di voi, carini! Siete stati allevati bene, ma il mio lavoro vi sembrerà abbastanza duro. Vedrete se non sarà così.”

E così dicendo, mi se la bambina a filare un tessuto e diede al bambino un setaccio con il quale attingere l’acqua dal pozzo e lei andò nel bosco. Mentre la bambina era seduta alla rocca e piangeva amaramente perché non poteva filare, sentì il rumore un centinaio di zampette e da ogni buco e angolo della casetta arrivarono topolini ticchettando con le unghie sul pavimento e dicendo:

Bambina perché hai gli occhi arrossati?

Dacci un po’ di pane e ci avrai aiutati.

E la bambina diede loro il pane che le aveva dato la nonna. Poi i topi le dissero che la strega aveva una gatta che amava molto il prosciutto; se le avesse dato il prosciutto, essa avrebbero mostrato la strada per uscire dal bosco e nel frattempo loro avrebbero filato il tessuto per lei. Così la bambina uscì a cercare la gatta e mentre lo stava facendo incontrò il fratello in grande difficoltà perché non poteva trasportare l’acqua con un setaccio, visto che l’acqua usciva più in fretta di quanto vi entrasse. Mentre stava cercando di consolarlo, sentirono un frullare d’ali e uno stormo di scriccioli si posò sul terreno accanto a loro. Gli scriccioli dissero.

Dacci un po’ di briciole e non ti accorare

perché l’acqua nel setaccio faremo restare.

Allora i gemelli sbriciolarono per terra il pane e gli scriccioli lo beccarono, cinguettando e trillando. Quando ebbero mangiato fino all’ultima briciola, dissero al bambino di riempire i buchi del setaccio con l’argilla e poi di attingere l’acqua dal pozzo. Così fece come gli avevano detto e portò nella casetta il setaccio pieno d’acqua senza rovesciarne una goccia. Quando entrarono in casa, la gatta era acciambellato sul pavimento. Così l’accarezzarono, le diedero da mangiare il prosciutto e le dissero:

“Micetta, micetta grigia, ci dici come scappare via dalla strega?”

Allora la gatta li ringraziò per il prosciutto e diede loro un fazzoletto da tasca e un pettine e disse che quando la strega li avesse inseguiti, come di certo avrebbe fatto, tutto ciò che dovevano fare sarebbe stato gettare il fazzoletto per terra e correre più in fretta che potevano. Appena il fazzoletto avesse toccato terra, ne sarebbe scaturito un fiume profondo e impetuoso che avrebbe ostacolato l’inseguimento della strega. Se fosse riuscita a superalo, dovevano gettare dietro di loro il pettine e correre a gambe levate perché dal pettine si sarebbe levata una fitta foresta che avrebbe ritardato tanto a lungo la strega che sarebbero riusciti a mettersi in salvo.

La gatta aveva appena finito di parlare che la strega tornò per vedere se i bambini avessero eseguito i compiti.

“Siete stati abbastanza bravi per oggi,” borbottò “ma domani avrete qualcosa di più difficile da fare e se non lo farete bene, monelli viziati, finirete dritti nel forno.”

Mezzi morti di paura e tremanti dalla testa ai piedi i poveri bambini si sdraiarono a dormire su un mucchio di paglia in un angolo della casetta, ma non osavano chiudere gli occhi e respiravano a malapena. La mattina la strega diede alla bambina due pezze di lino da tessere prima di notte e al bambino una catasta di legna da fare a pezzi. Poi li lasciò ai loro compiti e andò nel bosco. Appena l’ebbero persa di vista, i bambini presero il fazzoletto e il pettine e, tenendosi per mano, scapparono e corsero, corsero, corsero. Prima incontrarono il cane da guardia che stava per gettarsi su di loro e farli a pezzi, ma gli lanciarono i resti del pane e li mangiò, agitando la coda. Poi furono intralciati dalla betulla, i cui rami quasi cavarono loro gli occhi. Ma la sorellina legò i ramoscelli con un pezzo di nastro e poterono passare sani e salvi e, dopo aver corso nel bosco, giunsero nei campi.

Nel frattempo nella casetta la gatta era occupata a tessere il lino e a ingarbugliare i fili mentre tesseva. La strega tornò per vedere come si stessero comportando i bambini e sgusciò dalla finestra e sussurrò:

“Stai tessendo, mia cara?”

“Sì, nonna, sto tessendo.” rispose la gatta.

Quando la strega vide che i bambini erano scappati, s’infuriò e, colpendo la gatta con un una scodella per la pappa d’avena, disse: “Perché hai lasciato che i bambini scappassero di casa? Perché non hai cavato loro gli occhi?”

Ma la gatta arrotolò la coda, le volse le spalle e disse: “Ti ho servita per tutti questi anni e non mi hai mai dato un osso, ma quei cari bambini mi hanno dato il loro pezzo di prosciutto.”

Allora la strega s’infuriò con il cane da guardia e con le betulle perché avevano lasciato passare i bambini. Ma il cane rispose:

“Ti ho servita per tutti questi anni e tu non mi hai mai dato neppure una crosticina di pane, ma i cari bambini mi hanno dato la loro pagnotta.”

E la betulla fece frusciare le foglie e disse: “Ti ho servita più a lungo di quanto posa dire e tu non mi hai mai legato un pezzetto di spago intorno ai rami; i cari bambini mi hanno intrecciata con i loro nastri.”

Così la strega vide che era stato inutile contare sui vecchi servitori e che la cosa migliore da fare sarebbe stata montare sul manico della scopa e gettarsi all’inseguimento dei bambini. Mentre i bambini correvano, potevano sentire il suono della scopa che spazzava il terreno dietro di loro così gettarono subito il fazzoletto alle loro spalle e in un attimo sgorgò dietro di loro un fiume vasto e profondo.

Quando la strega vi giunse, perse un po’ di tempo per trovare un punto che potesse guadare con il suo manico di scopa, ma alla fine lo attraversò e continuò a inseguirli come prima. Mentre i bambini correvano, sentirono un suono e la bambina appoggiò l’orecchio a terra e sentì la scopa che spazzava il terreno dietro di loro; così, veloce come il pensiero, gettò a terra il pettine e in un attimo, come aveva detto la gatta, una fitta foresta s’innalzò, con le radici e i rami così intrecciati che era impossibile aprirsi a forza un varco. Così quando giunse sulla sua scopa, vide che non poteva far altro che voltarsi e tornare a casa.

Ma i gemelli corsero a perdifiato finché giunsero a casa. Lì raccontarono al padre tutto ciò che avevano patito e lui si arrabbiò tanto con la matrigna che la cacciò di casa e lei non tornò mai più; lui e i suoi bambini vissero felici insieme e si presero cura di loro stessi e non lasciaro mai più avvicinare un estraneo.

Fiaba russa.

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)