In the great country far away south, through which flows the river Nile, there lived a king who had an only child called Samba.

Now, from the time that Samba could walk he showed signs of being afraid of everything, and as he grew bigger he became more and more frightened. At first his father’s friends made light of it, and said to each other:

‘It is strange to see a boy of our race running into a hut at the trumpeting of an elephant, and trembling with fear if a lion cub half his size comes near him; but, after all, he is only a baby, and when he is older he will be as brave as the rest.’

‘Yes, he is only a baby,’ answered the king who overheard them, ‘it will be all right by-and-by.’ But, somehow, he sighed as he said it, and the men looked at him and made no reply.

The years passed away, and Samba had become a tall and strong youth. He was good-natured and pleasant, and was liked by all, and if during his father’s hunting parties he was seldom to be seen in any place of danger, he was too great a favourite for much to be said.

‘When the king holds the feast and declares him to be his heir, he will cease to be a child,’ murmured the rest of the people, as they had done before; and on the day of the ceremony their hearts beat gladly, and they cried to each other:

‘It is Samba, Samba, whose chin is above the heads of other men, who will defend us against the tribes of the robbers!’

Not many weeks after, the dwellers in the village awoke to find that during the night their herds had been driven away, and their herdsmen carried off into slavery by their enemies. Now was the time for Samba to show the brave spirit that had come to him with his manhood, and to ride forth at the head of the warriors of his race. But Samba could nowhere be found, and a party of the avengers went on their way without him.

It was many days later before he came back, with his head held high, and a tale of a lion which he had tracked to its lair and killed, at the risk of his own life. A little while earlier and his people would have welcomed his story, and believed it all, but now it was too late.

‘Samba the Coward,’ cried a voice from the crowd; and the name stuck to him, even the very children shouted it at him, and his father did not spare him. At length he could bear it no longer, and made up his mind to leave his own land for another where peace had reigned since the memory of man. So, early next morning, he slipped out to the king’s stables, and choosing the quietest horse he could find, he rode away northwards.

Never as long as he lived did Samba forget the terrors of that journey. He could hardly sleep at night for dread of the wild beasts that might be lurking behind every rock or bush, while, by day, the distant roar of a lion would cause him to start so violently, that he almost fell from his horse. A dozen times he was on the point of turning back, and it was not the terror of the mocking words and scornful laughs that kept him from doing so, but the terror lest he should be forced to take part in their wars. Therefore he held on, and deeply thankful he felt when the walls of a city, larger than he had ever dreamed of, rose before him.

Drawing himself up to his full height, he rode proudly through the gate and past the palace, where, as was her custom, the princess was sitting on the terrace roof, watching the bustle in the street below.

‘That is a gallant figure,’ thought she, as Samba, mounted on his big black horse, steered his way skilfully among the crowds; and, beckoning to a slave, she ordered him to go and meet the stranger, and ask him who he was and whence he came.

‘Oh, princess, he is the son of a king, and heir to a country which lies near the Great River,’ answered the slave, when he had returned from questioning Samba. And the princess on hearing this news summoned her father, and told him that if she was not allowed to wed the stranger she would die unmarried.

Like many other fathers, the king could refuse his daughter nothing, and besides, she had rejected so many suitors already that he was quite alarmed lest no man should be good enough for her. Therefore, after a talk with Samba, who charmed him by his good humour and pleasant ways, he gave his consent, and three days later the wedding feast was celebrated with the utmost splendour.

The princess was very proud of her tall handsome husband, and for some time she was quite content that he should pass the days with her under the palm trees, telling her the stories that she loved, or amusing her with tales of the manners and customs of his country, which were so different to those of her own. But, by-and-by, this was not enough; she wanted other people to be proud of him too, and one day she said:

‘I really almost wish that those Moorish thieves from the north would come on one of their robbing expeditions. I should love so to see you ride out at the head of our men, to chase them home again. Ah, how happy I should be when the city rang with your noble deeds!’

She looked lovingly at him as she spoke; but, to her surprise, his face grew dark, and he answered hastily:

‘Never speak to me again of the Moors or of war. It was to escape from them that I fled from my own land, and at the first word of invasion I should leave you for ever.’

‘How funny you are,’ cried she, breaking into a laugh. ‘The idea of anyone as big as you being afraid of a Moor! But still, you mustn’t say those things to anyone except me, or they might think you were in earnest.’

Not very long after this, when the people of the city were holding a great feast outside the walls of the town, a body of Moors, who had been in hiding for days, drove off all the sheep and goats which were peacefully feeding on the slopes of a hill. Directly the loss was discovered, which was not for some hours, the king gave orders that the war drum should be beaten, and the warriors assembled in the great square before the palace, trembling with fury at the insult which had been put upon them. Loud were the cries for instant vengeance, and for Samba, son-in-law of the king, to lead them to battle. But shout as they might, Samba never came.

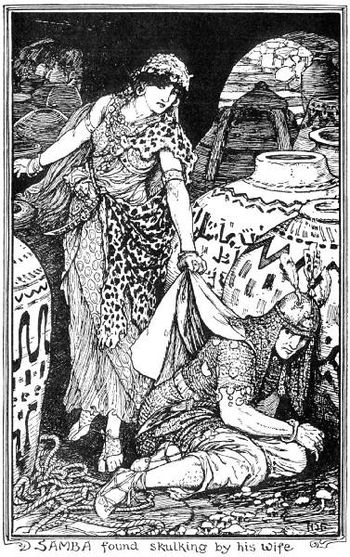

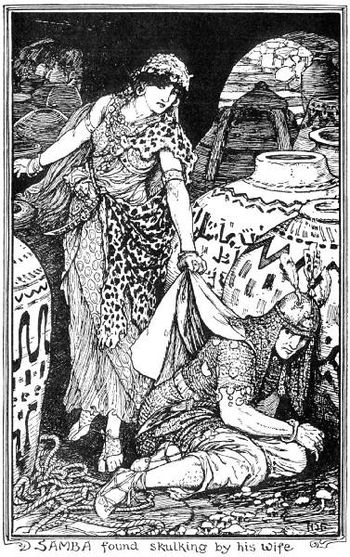

And where was he? No further than in a cool, dark cellar of the palace, crouching among huge earthenware pots of grain. With a rush of pain at her heart, there his wife found him, and she tried with all her strength to kindle in him a sense of shame, but in vain. Even the thought of the future danger he might run from the contempt of his subjects was as nothing when compared with the risks of the present.

‘Take off your tunic of mail,’ said the princess at last; and her voice was so stern and cold that none would have known it. ‘Give it to me, and hand me besides your helmet, your sword and your spear.’ And with many fearful glances to right and to left, Samba stripped off the armour inlaid with gold, the property of the king’s son-in-law. Silently his wife took, one by one, the pieces from him, and fastened them on her with firm hands, never even glancing at the tall form of her husband who had slunk back to his corner. When she had fastened the last buckle, and lowered her vizor, she went out, and mounting Samba’s horse, gave the signal to the warriors to follow.

Now, although the princess was much shorter than her husband, she was a tall woman, and the horse which she rode was likewise higher than the rest, so that when the men caught sight of the gold-inlaid suit of chain armour, they did not doubt that Samba was taking his rightful place, and cheered him loudly. The princess bowed in answer to their greeting, but kept her vizor down; and touching her horse with the spur, she galloped at the head of her troops to charge the enemy. The Moors, who had not expected to be so quickly pursued, had scarcely time to form themselves into battle array, and were speedily put to flight. Then the little troop of horsemen returned to the city, where all sung the praises of Samba their leader.

The instant they reached the palace the princess flung her reins to a groom, and disappeared up a side staircase, by which she could, unseen, enter her own rooms. Here she found Samba lying idly on a heap of mats; but he raised his head uneasily as the door opened and looked at his wife, not feeling sure how she might act towards him. However, he need not have been afraid of harsh words: she merely unbuttoned her armour as fast as possible, and bade him put it on with all speed. Samba obeyed, not daring to ask any questions; and when he had finished the princess told him to follow her, and led him on to the flat roof of the house, below which a crowd had gathered, cheering lustily.

‘Samba, the king’s son-in-law! Samba, the bravest of the brave! Where is he? Let him show himself!’ And when Samba did show himself the shouts and applause became louder than ever. ‘See how modest he is! He leaves the glory to others!’ cried they. And Samba only smiled and waved his hand, and said nothing.

Out of all the mass of people assembled there to do honour to Samba, one alone there was who did not shout and praise with the rest. This was the princess’s youngest brother, whose sharp eyes had noted certain things during the fight which recalled his sister much more than they did her husband. Under promise of secrecy, he told his suspicions to the other princes, but only got laughed at, and was bidden to carry his dreams elsewhere.

‘Well, well,’ answered the boy, ‘we shall see who is right; but the next time we give battle to the Moors I will take care to place a private mark on our commander.’

In spite of their defeat, not many days after the Moors sent a fresh body of troops to steal some cattle, and again Samba’s wife dressed herself in her husband’s armour, and rode out at the head of the avenging column. This time the combat was fiercer than before, and in the thick of it her youngest brother drew near, and gave his sister a slight wound on the leg. At the moment she paid no heed to the pain, which, indeed, she scarcely felt; but when the enemy had been put to flight and the little band returned to the palace, faintness suddenly overtook her, and she could hardly stagger up the staircase to her own apartments.

‘I am wounded,’ she cried, sinking down on the mats where he had been lying, ‘but do not be anxious; it is really nothing. You have only got to wound yourself slightly in the same spot and no one will guess that it was I and not you who were fighting.’

‘What!’ cried Samba, his eyes nearly starting from his head in surprise and terror. ‘Can you possibly imagine that I should agree to anything so useless and painful? Why, I might as well have gone to fight myself!’

‘Ah, I ought to have known better, indeed,’ answered the princess, in a voice that seemed to come from a long way off; but, quick as thought, the moment Samba turned his back she pierced one of his bare legs with a spear.

He gave a loud scream and staggered backwards, from astonishment, much more than from pain. But before he could speak his wife had left the room and had gone to seek the medicine man of the palace.

‘My husband has been wounded,’ said she, when she had found him, ‘come and tend him with speed, for he is faint from loss of blood.’ And she took care that more than one person heard her words, so that all that day the people pressed up to the gate of the palace, asking for news of their brave champion.

‘You see,’ observed the king’s eldest sons, who had visited the room where Samba lay groaning, ‘you see, O wise young brother, that we were right and you were wrong about Samba, and that he really did go into the battle.’ But the boy answered nothing, and only shook his head doubtfully.

It was only two days later that the Moors appeared for the third time, and though the herds had been tethered in a new and safer place, they were promptly carried off as before. ‘For,’ said the Moors to each other, ‘the tribe will never think of our coming back so soon when they have beaten us so badly.’

When the drum sounded to assemble all the fighting men, the princess rose and sought her husband.

‘Samba,’ cried she, ‘my wound is worse than I thought. I can scarcely walk, and could not mount my horse without help. For to-day, then, I cannot do your work, so you must go instead of me.’

‘What nonsense,’ exclaimed Samba, ‘I never heard of such a thing. Why, I might be wounded, or even killed! You have three brothers. The king can choose one of them.’ ‘They are all too young,’ replied his wife; ‘the men would not obey them. But if, indeed, you will not go, at least you can help me harness my horse.’ And to this Samba, who was always ready to do anything he was asked when there was no danger about it, agreed readily.

So the horse was quickly harnessed, and when it was done the princess said:

‘Now ride the horse to the place of meeting outside the gates, and I will join you by a shorter way, and will change places with you.’ Samba, who loved riding in times of peace, mounted as she had told him, and when he was safe in the saddle, his wife dealt the horse a sharp cut with her whip, and he dashed off through the town and through the ranks of the warriors who were waiting for him. Instantly the whole place was in motion. Samba tried to check his steed, but he might as well have sought to stop the wind, and it seemed no more than a few minutes before they were grappling hand to hand with the Moors.

Then a miracle happened. Samba the coward, the skulker, the terrified, no sooner found himself pressed hard, unable to escape, than something sprang into life within him, and he fought with all his might. And when a man of his size and strength begins to fight he generally fights well.

That day the victory was really owing to Samba, and the shouts of the people were louder than ever. When he returned, bearing with him the sword of the Moorish chief, the old king pressed him in his arms and said:

‘Oh, my son, how can I ever show you how grateful I am for this splendid service?’

But Samba, who was good and loyal when fear did not possess him, answered straightly:

‘My father, it is to your daughter and not to me to whom thanks are due, for it is she who has turned the coward that I was into a brave man.’

(Contes Soudainais. Par C. Monteil.)

Samba il codardo

In un grande paese nel lontano sud, nel quale scorre il fiume Nilo, viveva un re che aveva un solo figlio di nome Samba.

Sin da quando aveva incominciato a camminare, dava segno di aver paura di tutto, e più cresceva, più si faceva pauroso. Dapprima gli amici di suo padre lo disprezzavano e si dicevano l’uno con l’altro:

”È strano vedere un bambino della nostra razza che corre a nascondersi in una capanna al barrire di un elefante, e trema di paura se gli si avvicina un leoncino la metà di lui; dopotutto, però è solo un bambino, e quando sarà grande, sarà coraggioso come tutti gli altri.”

”Sì, è solo un bambino,” rispose il padre, che li aveva sentiti casualmente, “tra non molto tutto andrà bene.” Ma, per qualche motivo, sospirava dicendolo, e gli uomini lo guardavano senza rispondere.

Gli anni trascorsero e Samba era diventato un giovane alto e forte. Era buono e simpatico, amato da tutti, e se durante le battute di caccia di suo padre raramente lo si vedeva in qualche situazione di pericolo, era prediletto da troppi perché lo si dicesse.

”Quando il re darà una festa e lo proclamerà suo erede, non sarà più un bambino.” mormorava il resto della popolazione, come aveva fatto prima; e il giorno della cerimonia i loro cuori batterono di gioia e gridarono l’un l’altro:

”È Samba, Samba, il cui mento sovrasta le teste degli altri uomini, che ci difenderà dalle tribù dei predoni!”

Non molte settimane dopo, gli abitanti del villaggio si svegliarono scoprendo che durante la notte le mandrie erano state portate via e i mandriani ridotti in schiavitù dai nemici. Adesso per Samba era il momento di mostrare lo spirito ardimentoso che era sopraggiunto insieme con l’età adulta e di cavalcare alla testa dei guerrieri della sua razza. Ma Samba non si trovava da nessuna parte, e una brigata di vendicatori si mise in cammino senza di lui.

Egli tornò solo dopo molti giorni più tardi, con la testa eretta e la storia di un leone che aveva inseguito fino alla sua tana e ucciso, a rischio della propria vita. Appena un poco prima la sua gente avrebbe accolto con piacere la storia e creduto a tutto, ma ora era troppo tardi.

”Samba il codardo,” gridava la folla a una sola voce; e il soprannome gli rimase addosso, persino i bambini glielo gridavano, e suo padre non aveva riguardo per lui. Alla fine non poté sopportarlo più e decise di lasciare il proprio paese per un altro in cui la pace regnasse sin da quando l’uomo ne avesse memoria. Così la mattina dopo, di buon’ora, scivolò fino alle stalle reali e, scegliendo il cavallo più tranquillo che ci fosse, se ne andò verso nord.

Samba non avrebbe dimenticato finché fosse vissuto i terrori di quel viaggio. La notte dormiva a malapena per la paura delle belve feroci che potevano nascondersi dietro ogni roccia o ogni cespuglio mentre, di giorno, il ruggito di un leone in lontananza lo faceva partire così violentemente che quasi cadeva da cavallo. Una dozzina di volte fu sul punto di tornare indietro, e non per il terrore delle parole di derisione e delle risate sprezzanti che gliene sarebbero venute, ma per la paura di essere costretto a partecipare alle loro guerre. Perciò si trattenne e fu profondamente grato quando gli si pararono davanti le mura di una città, più grande di quanto avesse mai sognato.

Ergendosi in tutta la propria altezza, cavalcò orgogliosamente attraverso il cancello e verso il palazzo in cui, com’era sua abitudine, la principessa era seduta in una terrazza sopraelevata a osservare il trambusto nella strada sottostante.

”Che tipo eroico,” pensò, mentre Samba, ritto sul grosso cavallo nero, si faceva strada abilmente tra la folla; e, facendo cenno a uno schiavo di avvicinarsi, gli ordinò di andare incontro allo straniero e di chiedergli chi fosse e da dove venisse.

”Principessa, è il figlio di un re e viene da un paese vicino al Grande Fiume,” rispose lo schiavo, quando fu tornato dall’aver interrogato Samba. Sentendo queste notizie, la principessa chiamò il padre e gli disse che, se le fosse stato vietato di sposare lo straniero, sarebbe morta zitella.

Come molti altri padri, il re non rifiutava nulla alla figlia, e per giunta aveva respinto così tanti corteggiatori che oramai era del tutto timoroso che nessun uomo andasse abbastanza bene per lei. Perciò, dopo aver parlato con Samba, che lo affascinò con il buonumore e le maniere affabili, dette il proprio consenso e tre giorni più tardi fu celebratala festa di nozze con il massimo sfarzo.

La principessa era assai orgogliosa del marito alto e affascinante e per un po’ di tempo fu completamente contenta che trascorresse i giorni con lei sotto le palme, narrandole storie che le piacevano o divertendo con il racconto degli usi e dei costumi del suo paese, che erano così diversi dal proprio. Pero, di lì a poco, ciò non bastò più: voleva che anche le altre persone fossero orgogliose di lui e un giorno disse:

”Vorrei davvero che quei predoni Mori del nord organizzassero una delle loro razzie. Mi piacerebbe tanto vederti cavalcare alla testa dei nostri uomini per rispedirli a casa loro. Ah, come sarei felice che la città risuonasse delle tue nobili imprese!”

Mentre gli parlava, lo guardava amorevolmente; con sua sorpresa, però, il suo volto si fece scuro e le rispose con impazienza:

”Non parlami mai più di nuovo dei Mori o della guerra. Per sfuggirli ho lasciato il mio paese e al primo cenno di invasione, ti lascerò per sempre.”

”Come sei divertente,” gridò lei, scoppiando a ridere. “L’idea che uno grande come te abbia paura dei Mori! Non devi dire e nessuno queste cose, eccetto me, o potrebbero pensare tu faccia sul serio.”

Non molto dopo tutto ciò, quando la popolazione della città stava facendo festa fuori delle mura cittadine, un drappello di Mori, che era rimasto nascosto per giorni, portò via tutte le pecore e le capre che stavano pascolando tranquillamente sulle pendici di una collina. Appena fu scoperta la perdita, il che non avvenne per diverse ore, il re diede ordine che suonassero i tamburi di guerra e i guerrieri si radunarono nella grande piazza davanti al palazzo, frementi di collera per l’insulto patito. Ci furono alte grida di immediata vendetta e per Samba, genero del re, che li conducesse in battaglia. M per quanto gridassero, Samba non venne.

E dov’era? Non più in la della fresca e buia cantina del palazzo, accucciato tra enormi pentole di terraglia piene di grano. Con un senso di pena nel cuore, lì lo trovò la moglie e tentò con tutte le proprie forze di suscitare in lui un senso di vergogna, ma invano. Nemmeno il pensiero del pericolo futuro che avrebbero corso i sudditi era nulla di paragonabile al rischio del presente.

Togliti la cotta di maglia,” disse al principessa alla fine; la sua voce era severa e fredda come non mai “dammela, e passami anche l’elmo, la spada e gli speroni.” E con molte occhiate timorose a destra e a manca, Simba si spogliò dell’armatura intarsiata d’oro, appartenente al genero del re. Silenziosamente la moglie gli prese i pezzi a uno a uno, e se li assicurò con mani salde, senza degnare di uno sguardo l’alta figura del marito che se la svignava dall’angolo. Quando ebbe allacciato l’ultima fibbia e abbassato la visiera, se ne andò; balzando sul cavallo di Samba, fece segno ai guerrieri di seguirla.

Dovete sapere che, sebbene la principessa fosse più bassa del marito, era una donna alta e anche il cavallo che montava era più alto degli altri, cosicché gli uomini, quando diedero un’occhiata alla cotta di maglia intarsiata d’oro, non dubitarono che samba avesse preso il posto che gli spettava e lo acclamarono a gran voce. La principessa si inchinò in risposta al loro saluto, ma tenne la visiera abbassata; e, toccando il cavallo con gli speroni, cavalcò alla testa delle truppe per caricare il nemico. I Mori, che non si aspettavano di essere inseguiti così rapidamente, ebbero a malapena il tempo di mettersi in formazione da battaglia e furono rapidamente messi in fuga. Poi il piccolo drappello di cavalieri tornò in città, dove tutti celebrarono il loro comandante Samba.

Nel momento in cui raggiunsero il palazzo, la principessa gettò le redini a uno stalliere e sparì lungo una scala, che l’avrebbe condotta con discrezione nelle sue stanze. Lì trovò Samba, pigramente sdraiato su un mucchio di tappeti; alzò la testa turbato all’aprirsi della porta e alla vista della moglie, non sapendo che cosa aspettarsi da lei. Tuttavia non doveva temere parole dure: lei si limitò a liberarsi il più in fretta possibile dell’armatura e gli ordinò di indossarla rapidamente. Samba obbedì, non osando fare domande; quando ebbe finito, la principessa gli disse di seguirla e lo condusse sulla terrazza del palazzo, sotto la quale la folla si era radunata, acclamandolo vivacemente.

”Samba, il genero del re! Samba, il più coraggioso tra i coraggiosi! Dov’è? Lasciate che si mostri!” e quando Samba si mostrò, le grida e gli applausi si fecero più sonori che mai. “Guardate com’è modesto! Lascia agli altri la gloria!” gridavano. E Samba sorrideva soltanto e agitava la mano, senza dire nulla.

Tra tutti coloro che erano radunati lì a rendere onore a Samba, solo uno non gridava e non acclamava come gli altri. Era il fratello più giovane della principessa, i cui occhi acuti avevano notato certi particolari durante la battaglia che gli avevano fatto pensare più a sua sorella che al marito. Imponendo la segretezza, raccontò i propri sospetti agli altri principi, ma loro si limitarono a ridere e gli fu detto di indirizzare altrove le proprie fantasie.

”Ebbene,” rispose il ragazzo, “vedremo chi ha ragione; la prossima volta in cui daremo battaglia ai Mori, mi curerò di mettere un segno particolare sul nostro comandante.”

Malgrado la sconfitta, pochi giorni dopo i Mori mandarono un nuovo drappello a rubare un po’ di bestiame, e di nuovo la moglie di Samba indossò l’armatura del marito e cavalcò alla testa delle truppe vendicatrici. Stavolta il combattimento fu più aspro del precedente e, nel bel mezzo della battaglia, il fratello più giovane le si avvicinò e le inferse una lieve ferita sulla gamba. In quel momento non si curò del dolore, che in verità sentiva appena; ma quando i nemici furono dispersi e il piccolo drappello tornò a palazzo, la debolezza improvvisamente la sopraffece e poté a malapena salire le scale verso il suo appartamento.

”Sono stata ferita,” esclamò, sprofondando sui tappeti sui quali lui era stato sdraiato, “ma non preoccuparti, non è nulla. Devi solo procurarti una ferita nel medesimo punto e nessuno immaginerà che sia stata io a combattere e non tu.”

”Che cosa!” gridò Samba, con gli occhi fuori dalle orbite per lo stupore e per il terrore. “Puoi immaginare che io accetti qualcosa di così vano e doloroso? Sarebbe stato meglio se fossi andato a combattere io stesso!”

”Avrei dovuto ben saperlo, in verità,” rispose la principessa, con una voce che sembrava uscire dal profondo; ma, rapida come il pensiero, nel momento in cui Samba le voltò le spalle, bucò una delle sue gambe nude con uno sperone.

Egli lanciò un forte grido e barcollò all’indietro, più per lo stupore che per il dolore. Ma prima che potesse parlare, sua moglie aveva lasciato la stanza ed era andata a cercare il medico di palazzo.

”Mio marito è stato ferito,” disse, quando l’ebbe trovato, “vieni a curarti di lui in fretta perché è debole per il sangue che ha perso.” Ed ebbe cura che più di una persona avesse udito le sue parole cosicché per tutto il giorno il popolo si assiepò al cancello del palazzo, chiedendo notizie del coraggioso campione.

”Vedi,” osservò il figlio maggiore del re, che aveva visitato la stanza in cui Samba giaceva gemendo, “vedi, saggio fratellino, che noi avevamo ragione e tu torto su Samba, che veramente è stato lui ad andare in battaglia.” Ma il ragazzino non rispose nulla e scosse solo testa dubbiosamente.

Solo due giorni più tardi i Mori apparvero per la terza volta, e sebbene le mandrie fossero state legate in un nuovo posto più sicuro, furono portate via con prontezza come la volta precedente. “Perché la tribù non penserà mai che siamo tornati così presto dopo essere stati battuti così gravemente.” si dissero i Mori l’un l’altro.

Quando i tamburi rullarono per radunare tutti i combattenti, la principessa si alzò e andò in cerca del marito.

”Samba,” esclamò, la mia ferita è peggiore di quanto pensassi. Posso a malapena camminare e non potrei montare a cavallo senza aiuto. Per oggi non posso fare il tuo lavoro, perciò devi andare tu al posto mio.”

”Che cosa insensata,” esclamò Samba, “non ho mai sentito nulla di simile. Potrei essere ferito o persino ucciso! Hai tre fratelli. Il re può scegliere uno di loro.”

”Sono troppo giovani,” rispose la moglie; “gli uomini non obbedirebbero loro. Se proprio non vuoi andare, almeno aiutami a mettere i finimenti al mio cavallo.” E Samba acconsentì volentieri a questa richiesta, essendo sempre pronto a fare qualsiasi cosa gli venisse chiesta quando non c’era pericolo.

Così il cavallo fu bardato in fretta e, quando fu pronto, la principessa disse:

”Adesso conduci il cavallo fuori, al luogo dell’appuntamento, e io mi riunirò a te per una strada più breve e scambierò il posto con te.” Samba, che gradiva cavalcare in tempo di pace, montò a cavallo come lei gli aveva detto e quando fu saldo in sella, sua moglie colpì il cavallo col frustino e l’animale attraversò la città e le fila dei guerrieri che lo stavano aspettando. Immediatamente l’intero luogo si mise in moto. Samba tentò di arrestare il destriero, ma sarebbe stato come tentare di fermare il vento, e ci vollero solo pochi minuti prima che si trovassero a lottare corpo a corpo con i Mori.

Allora avvenne il miracolo. Samba il codardo, lo scansafatiche, il pauroso, subito si trovò così duramente pressato, nell’impossibilità di scappare, che qualcosa si svegliò in lui e combatté con tutte le proprie forze. E quando un uomo delle sue dimensioni e forza comincia a combattere, generalmente combatte bene.

Quel giorno la vittoria fu davvero di Samba e le grida del popolo furono più alte che mai. Quando tornò, portando con sé la spada del capo dei Mori, il vecchio re lo strinse fra le braccia e disse:

”Figlio mio, come posso dimostrarti tutta la mia gratitudine per questo splendido servigio?”

Ma Samba, che era buono e leale quando non era preda della paura, rispose onestamente:

”Padre mio, è vostra figlia che dovete ringraziare, non me, perché lei ha trasformato il codardo che ero in un uomo coraggioso.”

Racconti del Sudan, raccolti da C. Monteil

(traduzione dall'inglese di Annarita Verzola)